Pancreatic trauma injuries are rare, representing 1%–4% of severe abdominal trauma injuries.1 They are usually caused by abdominal contusion, direct anterior compression, or high-energy trauma with significant deceleration, and less frequently by penetrating injuries. The diagnostic test of choice is abdominal CT scan with contrast, which has a sensitivity and specificity of 85% for detecting pancreatic injuries.2,3 Even so, it tends to underdiagnose this type of injury and is not useful for evaluating the integrity of the pancreatic duct. Instead, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), or sometimes endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), should be performed to determine whether there is contrast leakage.4,5

The most frequent complications of pancreatic trauma are: hemoperitoneum, pancreatitis, pancreatic fistula, pseudocyst, intra-abdominal abscess, ductal stenosis and splenic pseudoaneurysm.3

Trauma to the pancreas can be associated with injuries to other organs (especially the duodenum1,5 and spleen) and are more frequently located in the body/tail of the pancreas.5 There are several classifications for pancreatic injuries, and the most extensively used is the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) Pancreas Injury Scale.6

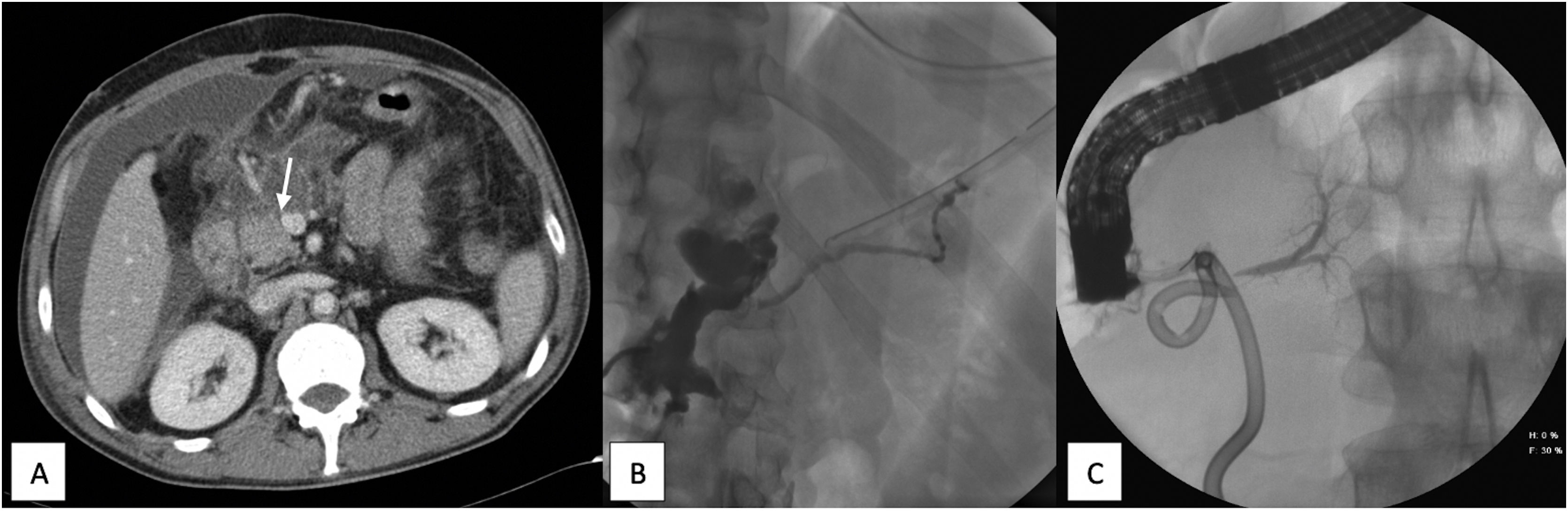

We describe the case of a 48-year-old male patient who presented various stab wounds in the abdomen, specifically the right upper quadrant, after having been assaulted with a knife. Upon arriving in the emergency room, he was hemodynamically unstable, so emergency surgery was indicated. Abundant hemoperitoneum was found due to hemorrhage from the right gastroepiploic artery and a liver laceration. Ten days after surgery, he presented abdominal pain, fever and a tendency towards tachycardia. An abdominal CT scan was performed, and a periduodenal collection was observed with abundant free fluid (Fig. 1A). Biochemical analysis of the sample obtained showed amylase >12 000 U/L, and a pigtail drain was inserted to drain the collection. MRCP revealed two collections (the largest 14 cm, caudal to the neck of the pancreas) with no apparent alterations in the bile duct or pancreas. An ERCP was indicated but unsuccessful due to duodenal compression.

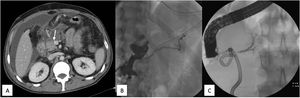

A) Abdominal CT with intravenous contrast showing periduodenal collection and intra-abdominal free fluid. The arrow indicates the neck of the pancreas, where the injury most likely occurred. B) Fistulography with filling of the collection and the distal Wirsung duct (dorsal pancreas). C) ERCP showing opacification of the pancreatic duct corresponding to the ventral pancreas, with no communication with the dorsal pancreas; no contrast extravasation.

After 5 weeks, the patient was reoperated for sepsis of abdominal origin, at which time a periduodenal collection and free fluid were observed, with no other findings; suction drains were left in place. In the early postoperative period, a discharge of about 300 cc of brownish fluid was observed, which had a very high level of amylase. Two months after the first surgery, the distal Wirsung duct was observed by fistulogram (Fig. 1B).

Later, the patient presented symptoms of sepsis associated with a retrogastric collection found by CT scan, which was treated with antibiotic therapy and placement of a pigtail catheter, followed by discharge of purulent pancreatic fluid. ERCP was performed; only the proximal part of the pancreatic duct corresponding to the ventral pancreas was opacified, showing no continuity with the dorsal pancreas or contrast extravasation (suggestive of pancreas divisum) (Fig. 1C).

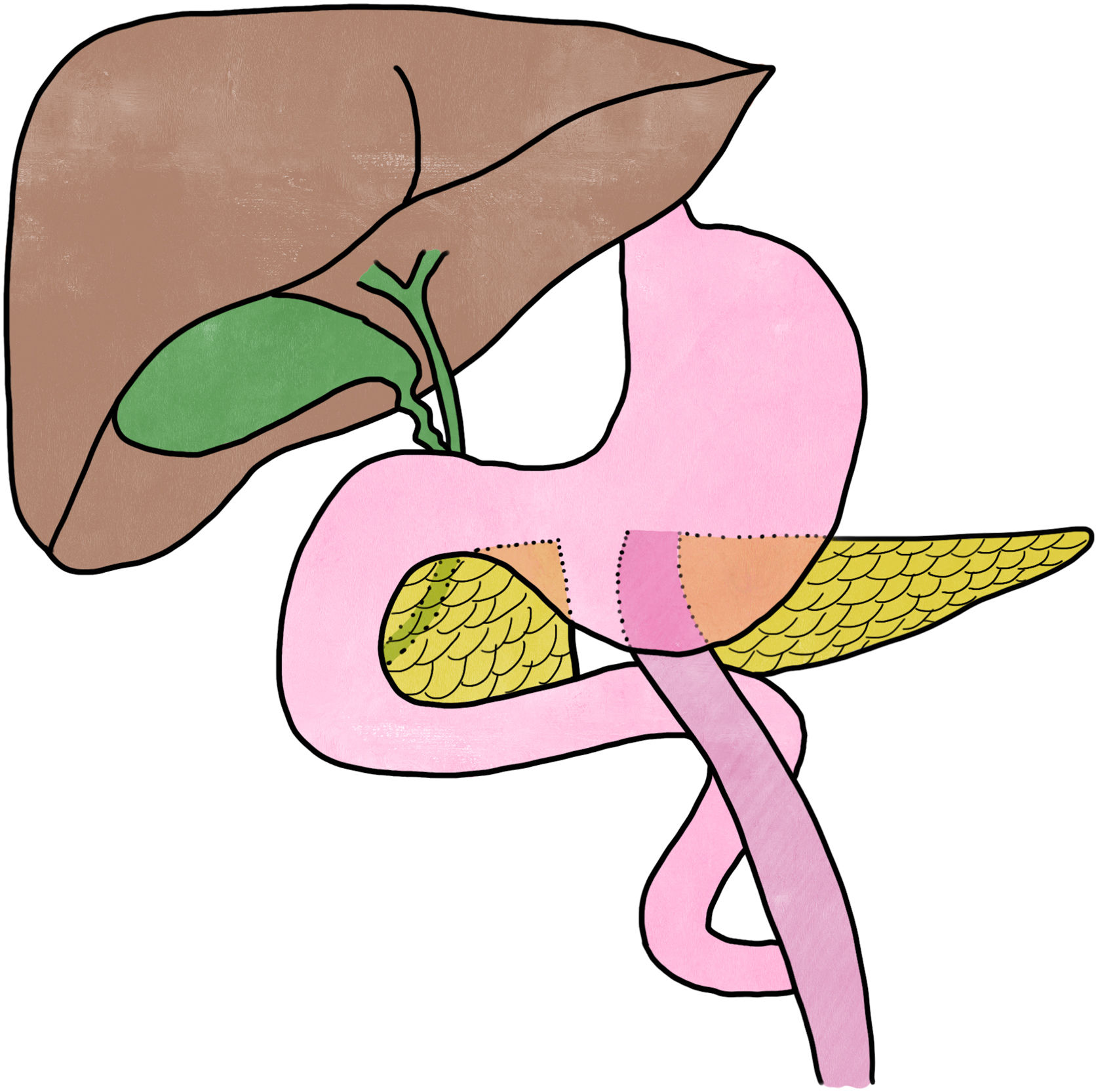

Subsequent CT scans demonstrated radiological stability, with an output of about 400cc per day of clear pancreatic fluid through the drain tube. Because the pancreatic fistula persisted despite conservative treatment, we decided to perform elective surgery 5 months after hospital admission. The neck of the pancreas was divided where the origin of the fistula was suspected. The proximal pancreas was sutured, and an end-to-side, duct-to-mucosa, Roux-en-Y pancreaticojejunostomy was performed (Fig. 2).

The patient then presented a perianastomotic collection (which required placement of a new pigtail catheter) and a surgical wound infection (which cultured Escherichia coli). He subsequently improved and was discharged 6 months after the assault. At the one-year follow-up, the patient was completely asymptomatic, with good oral intake and good glycemic control.

Unlike liver or spleen injuries, trauma injuries to the pancreas are a challenge for diagnosis. The delay in diagnosis can lead to an increase in morbidity and mortality, the latter reaching 34%.5 One of the determining factors in deciding treatment and anticipating possible complications is the integrity of the pancreatic duct,3,5,7 in addition to the extent of the parenchymal damage, location of the lesion, patient stability and presence of other injuries.

In cases where the patient is hemodynamically stable and the main pancreatic duct is shown to be intact, conservative treatment is an option. In hemodynamically unstable patients, damage-control surgery should be performed.7

The surgical treatment of these injuries is highly variable. It may simply require the placement of drains in the event of contusions and/or lacerations, distal pancreatectomy for complete divisions of the tail of the pancreas, and, in selected cases with injuries affecting the head of the pancreas or the intrapancreatic common bile duct, a two-stage pancreaticoduodenectomy has been described.4,7 The placement of stents in the pancreatic duct by ERCP in select cases has also been described, thereby avoiding distal pancreatectomy.4,8 If there is injury to the pancreatic duct and drainage without pancreatic resection is performed, the incidence of persistent pancreatic fistula is very high,9 except in cases where a pancreatic-enterostomy is performed.10

In the case we have reported, the patient presented a persistent pancreatic fistula due to ductal injury at the neck of the pancreas. We opted to perform Roux-en-Y pancreaticojejunostomy, closing the division of the proximal pancreas. This technique allows the pancreatic parenchyma to be preserved and prevents the patient from developing exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and diabetes mellitus, but it involves higher technical difficulty, more postoperative complexity, and possible serious adverse events.

Please cite this article as: Lucas Guerrero V, García Monforte MN, Romaguera Monzonis A, Badia Closa J, García Borobia F. Traumatismo pancreático: manejo de una fístula pancreática compleja. Cir Esp. 2022;100:110–112.