Varicella-zoster virus infection affects 10%–20% of the general population,1 with an incidence that varies between 3 and 5 per 1000 inhabitants/year.2 The neurological sequelae range from chronic pain (postherpetic neuralgia) to meningoencephalitis.3 Within the motor sequelae, postherpetic pseudohernias are due to segmental paresis and appear in less than 5% of cases as a protrusion of the abdominal wall in the absence of structural defects that increases with Valsalva maneuvers.4,5

We present the cases of 2 patients with postherpetic pseudohernia:

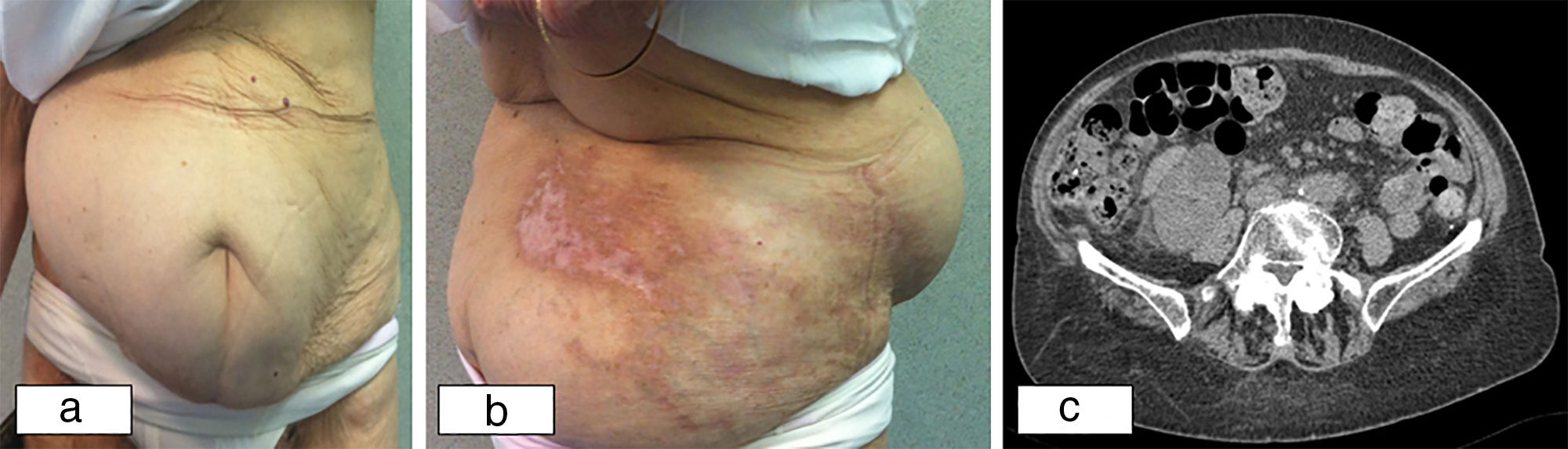

An 82-year-old woman was diagnosed with varicella-zoster virus infection after presenting characteristic lesions in the T12-L1 dermatome. She was treated with oral Acyclovir® for one week. Three months later, she presented a “bulge” in the region of the right abdominal wall that corresponded with the affected dermatome, which increased in size with the Valsalva maneuver. Upon physical examination, abdominal asymmetry was observed in the area of the abdominal wall mentioned previously (Fig. 1a), as well as a herpetic eruption in resolution (Fig. 1b). No hernia ring or wall defects were palpated. Computed tomography (CT) confirmed the absence of hernia defects (Fig. 1c) and electromyography revealed limited denervation to the muscles of the right T12-L1 dermatome region.

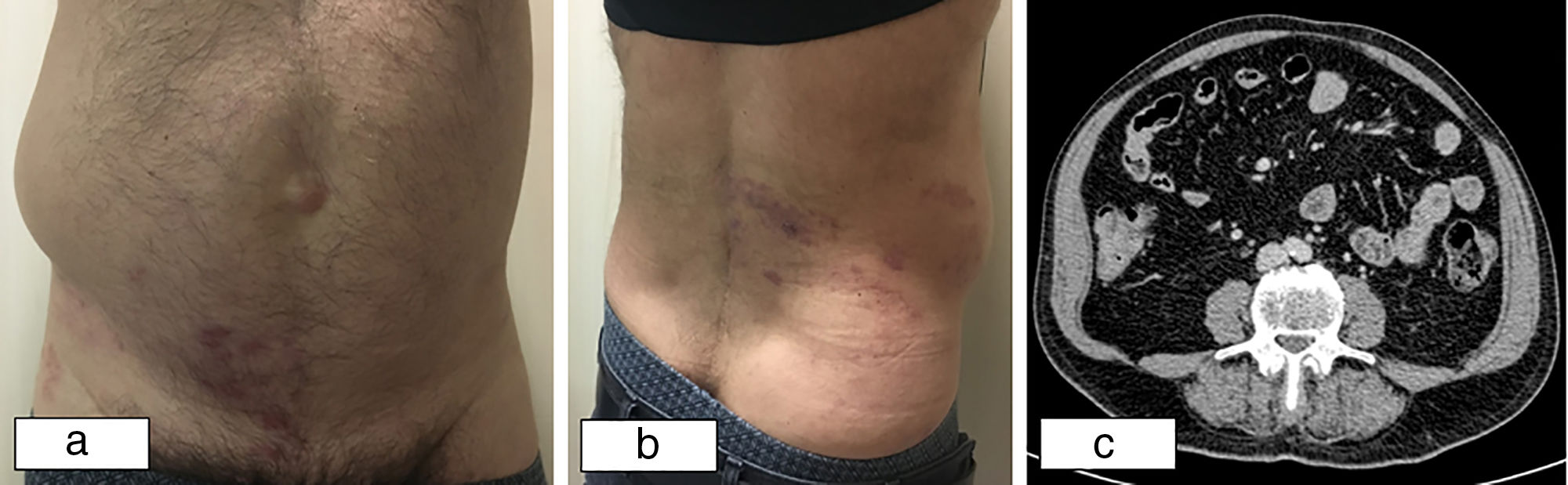

In the second case, a 67-year-old man presented clinical symptoms that were identical to the first case (Fig. 2b) and was treated with Valaciclovir® for one week (Fig. 2c).

A 67-year-old male with postherpetic pseudohernia: (a) frontal view with protrusion of the abdominal wall in the right flank; (b) posterolateral view with protrusion of the abdominal wall and herpetic eruption; (c) abdominal CT scan showing weakness of the right posterolateral abdominal wall with no observed hernia orifices.

The pathogenesis of postherpetic motor complications is controversial. It has been related to the direct propagation of the virus from the dorsal ganglia to the ventral roots or the anterior horns of the spinal cord,4,6 thereby generating muscle weakness and the resulting paresis.7,8 Abdominal zoster can cause protrusion of the wall, while cervical zoster causes weakness of the arm and the lumbosacral presentation causes bladder and intestinal dysfunction. The term ‘pseudohernia’ refers to the limited weakness of the abdominal wall with no clear defect or orifice, which occurs as a consequence of protruding intra-abdominal organs against the weakened wall due to positive intra-abdominal pressure. The average age at onset is at the end of the sixth decade of life and is more frequent among males.4

The diagnosis is made clinically and should be suspected in the presence of a vesicular rash, which may be either concomitant or 2–6 weeks prior (average latency is 3.5 weeks). In nearly 90% of cases, the appearance of the eruption precedes the abdominal wall weakness. In exceptional cases, dermatological involvement may never have occurred (zoster sine herpete in up to 8% of patients).9 The characteristic findings can be associated with a decrease in segmental reflexes and cutaneous hypoesthesia.10 Although the paresis of the abdominal muscles usually follows the distribution of the affected dermatome, pseudohernias in different areas have been reported.4 CT studies confirm the diagnosis by revealing the presence of abdominal wall muscle that is thinner than the contralateral muscle, with no herniated orifices. Electromyography can provide important information when detecting fibrillation potential, positive sharp waves or abnormal evoked responses in 95% of patients.4

The general prognosis for this entity is good, with spontaneous complete recovery in less than 6 months in 79% of cases.8 However, sometimes the paresis of the abdominal wall may be permanent. In our two cases, the woman continued to experience paresis for 2 years after diagnosis, while the man presented spontaneous recovery 2 months after the onset of symptoms. It is important to consider the diagnosis of pseudohernia to avoid unnecessary invasive surgical exploration or treatments in this pathology.

FundingThis study has received no specific funding from public, private or non-profit organizations.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare related with this article.

We would like to thank Dr. Josep Salvador, from the Radiodiagnostics Department at the Hospital Universitario Vall d’Hebron, for his significant collaboration.

Please cite this article as: Curell A, Ortega N, Protti GP, Balibrea JM, López-Cano M. Pseudohernia postherpética. Cir Esp. 2019;97:55–57.