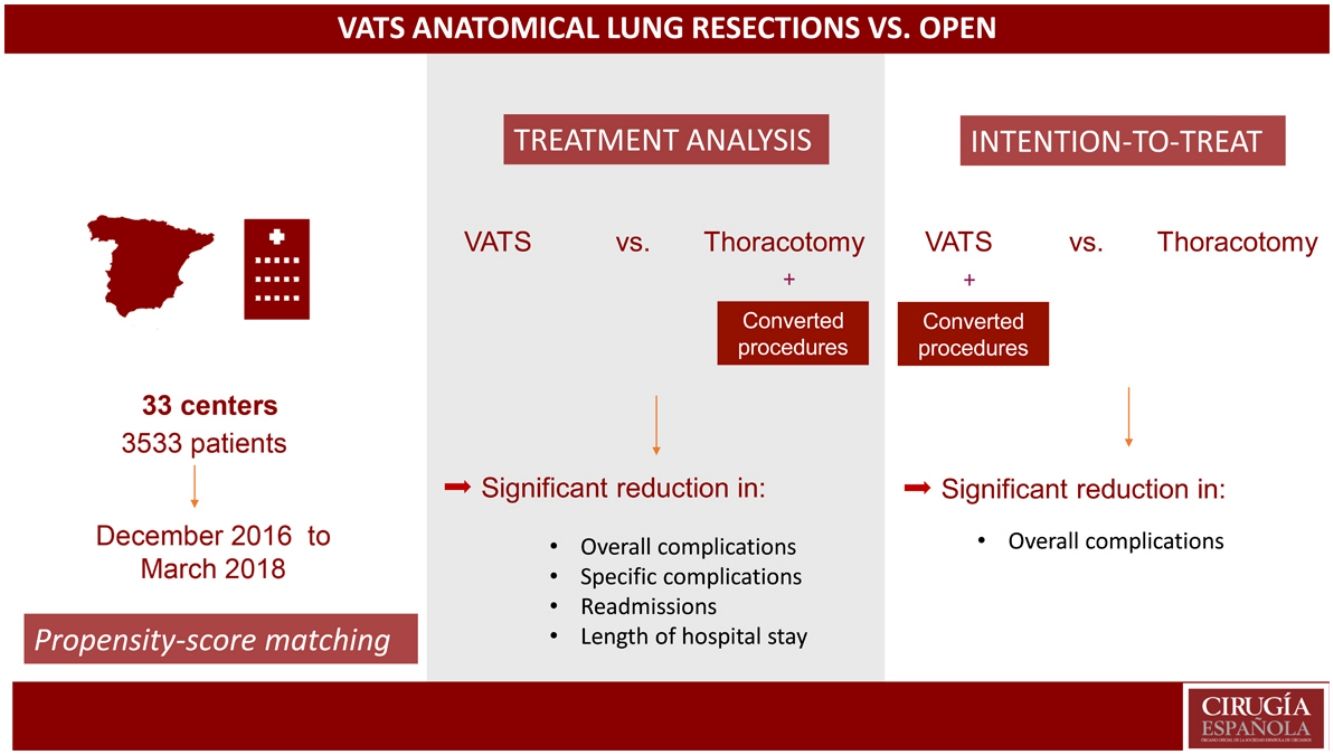

In recent years, video-assisted thoracoscopic lung resections (VATS) have been associated with lower morbidity than open surgery. The aim of our study is to compare postoperative morbidity among patients from the national database of the Spanish Group of Video-Assisted Thoracic Surgery (GE-VATS) after open and video-assisted anatomic lung resections using a propensity score analysis.

MethodsFrom December 2016 to March 2018, a total of 3533 patients underwent anatomical lung resection at 33 centers. Pneumonectomies and extended resections were excluded. A propensity score analysis was performed to compare the morbidity of the thoracotomy group (TG) vs the VATS group (VATSG). Treatment and intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses were conducted.

ResultsIn total, 2981 patients were finally included in the study: 1092 (37%) in the TG and 1889 (63%) in the VATSG for the treatment analysis; and 816 (27.4%) in the TG and 2165 patients (72.6%) in the VATSG for the ITT analysis. After propensity score matching, in the treatment analysis, the VATSG was significantly associated with fewer overall complications than the TG OR 0.680 [95%CI 0.616, 0.750]), fewer respiratory (OR 0.571 [0.529, 0.616]) cardiovascular (OR 0.529 [0.478, 0.609]) and surgical (OR 0.875 [0.802, 0.955]) complications, lower readmission rate (OR 0.669 [0.578, 0.775]) and a reduction of hospital length of stay (−1.741 ([−2.073, −1.410]). Intention-to-treat analysis showed only statistically significant differences in overall complications (OR 0.76 [0.54–0.99]) in favor of the VATSG.

ConclusionIn this multicenter population, VATS anatomical lung resections have been associated with lower morbidity than those performed by thoracotomy. However, when an intention-to-treat analysis was performed, the benefits of the VATS approach were less prominent.

El objetivo de nuestro estudio es comparar la morbilidad postoperatoria entre los pacientes de la base de datos nacional del Grupo Español de Cirugia Torácica Videoasistida (GE-VATS) después de resecciones pulmonares anatómicas abiertas y videoasistidas mediante un análisis de emparejamiento por índice de propensión.

MétodosDesde Diciembre de 2016 hasta Marzo de 2018, un total 3533 pacientes fueron intervenidos de resección pulmonar anatómica en 33 centros. Se excluyeron las neumonectomías y las resecciones extendidas. Se realizó un análisis de índice de propensión para comparar la morbilidad de cirugía abierta (TG) frente a VATS (VATSG). Se realizó un análisis por tratamiento y por intención de tratar (ITT).

ResultadosEn el estudio se incluyeron finalmente 2981 pacientes: 1092 (37%) en TG y 1889 (63%) en VATSG. En el análisis por tratamiento, la VATS se asoció significativamente con menor tasa de complicaciones que la cirugía abierta (OR 0.680 [95%CI 0.616, 0.750]), de complicaciones respiratorias (OR 0.571 [0.529, 0.616]), cardiovasculares (OR 0.529 [0.478, 0.609]) y quirúrgicas (OR 0.875 [0.802, 0.955]), menor tasa de reingresos (OR 0.669 [0.578, 0.775]) y menor estancia (−1.741 ([−2.073, −1.410]). En el de intención de tratar, se observaron diferencias estadísticamente significativas a favor de la VATS solo en las complicaciones en general (OR 0.76 [0.54–0.99]).

ConclusionesEn esta población multicéntrica, las lobectomías y segmentectomias anatómicas por VATS se han asociado con menor tasa de complicaciones que las realizadas por toracotomía. Sin embargo, en el análisis por intención de tratar, los beneficios de la VATS no fueron tan evidentes.

Video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) is becoming one of the most widely used approaches worldwide for the treatment of lung cancer. Meanwhile, the open thoracotomy approach continues to be performed, especially for advanced stages and large tumors. It is either selected by the surgeon, due to training or preferences, or it may be determined by the characteristics of the medical center and health care system.

According to published data, minimally invasive lung resections are reproducible, safe and offer our patients potential advantages over open surgery (especially in early stages [I and II]) with similar survival rates.1,2 In published randomized and propensity score studies, VATS showed significantly lower morbidity and shorter hospital stay than open procedures3–7 as well as less postoperative pain and better quality of life.8 However, these studies included a much higher percentage of patients operated by thoracotomy than by VATS. Also, most of the databases analyzed are retrospective and are not audited. Regarding selection bias, the studies do not include surgeon experience in the propensity score, which is considered a major deciding factor for the selection of the surgical approach. Moreover, the information about conversion from VATS to open surgery is not registered, even in the case of international registries.3,6

In 2016, the Spanish Society of Thoracic Surgery (SECT) developed a multicenter database to collect the data of all anatomical lung resections performed by 33 certified Spanish thoracic surgery centers, all of them members of the Spanish Video-Assisted Thoracic Surgery Group (GE-VATS). This project was primarily designed to determine the effect of VATS on the 90-day postoperative mortality rate after anatomic lung resection for lung cancer.9 The GE-VATS database is a prospective, audited database that represents the most ambitious prospective study of Spanish thoracic surgery to date due to the number of medical centers involved, the total number of patients, and the audit systems implemented to guarantee excellent data quality.

The objective of our study is to analyze postoperative morbidity among patients from the prospective, audited GE-VATS database after anatomic lung resection, comparing the VATS group (VATSG) and thoracotomy group (TG) using a propensity score analysis.

MethodsData source, patient population and ethical statementIn 2016, the Spanish Society of Thoracic Surgery (SECT) developed a prospective, multicenter database with the participation of 33 certified Spanish thoracic surgery centers, all members of the GE-VATS group. The project was approved by the ethics committee at each medical center, and informed consent was obtained from recruited patients to use their clinical data for scientific purposes. The necessary sample size was calculated based on the primary objective of the GE-VATS group9 (i.e., to demonstrate differences in the 90-day mortality rate based on the type of surgical approach). In total, 3533 patients who had undergone anatomical lung resections from December 2016 to March 2018 at participating GE-VATS hospitals were prospectively included. The inclusion criteria were: patients over 18 years of age who had undergone anatomical lung resections. In our study, patients who had undergone pneumonectomy (236 patients; 7%) were excluded. Also, patients who had undergone extended resections and sleeve resections were excluded (316 patients; 9%). There was no randomization in this study. Initially, interventions that had been converted to open procedures were included in the TG (treatment analysis). Then, a second analysis was conducted including conversions in VATSG with the aim of performing an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis.

Definition of resultAll descriptive and outcome variables were adapted from the standardization documents of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) and the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons (ESTS).10 Postoperative morbidity cases included those that occurred within 30 days of surgery or before hospital discharge. Complications were classified according to whether they were respiratory, cardiovascular, surgical, or other. Pulmonary complications included atelectasis requiring bronchoscopy, pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), reintubation and prolonged intubation. Cardiovascular complications included deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, arrhythmia, stroke, acute coronary events, acute heart failure, and postoperative blood transfusion. Surgical complications included bronchial fistula, prolonged air leak (>5 days), hemothorax requiring reoperation, chylothorax, empyema, and wound infection. Other complications included hematologic, urologic, gastric, psychiatric, metabolic, and urologic complications not previously described. VATS was defined by consensus as the absence of a rib retractor, regardless of the number of ports performed. Lymphadenectomy was performed by sampling or systematic lymph node dissection.11 The predicted postoperative forced expiratory volume in one second (ppoFEV1) and the predicted postoperative lung diffusion capacity (ppoDLCO) were calculated automatically, taking into account the number of segments resected in previous surgeries. Readmission was defined as the unscheduled admission of a patient within 30 days of discharge. Surgeon experience with VATS was defined as having performed more than 50 anatomical lung resections by VATS. Regarding tumor location, peripheral tumors were those located in the outer third of the lung. Induction treatments were chemotherapy, radiotherapy and immunotherapy.

Statistical analysisThe data collected from each patient included continuous variables (age, BMI [2.2% data missing], ppoFEV1 [1.3% data missing], ppoDLCO [16.2% data missing]), described as mean and standard deviation, and categorical variables (sex, American Society of Anesthesiologists [ASA] risk scale, smoking history, arterial hypertension, congestive heart failure, stroke, coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, arrhythmia, chronic renal failure, tumor location [13.8% missing], histology, stage [16.9% missing], induction treatment, previous thoracic surgery, type of resection, surgeon experience with VATS). Continuous variables were compared using the Student’s t test and Wilcoxon’s rank sum, and categorical variables were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test.

All missing data were handled via the multivariate imputation by chained equations (MICE) method.12 Incomplete dichotomous variables were imputed using a logistic regression model, categorical variables with more than 2 groups were imputed using a logistic multinomial model, and linear regression was used to impute incomplete continuous variables. Ten imputed data sets were generated.

In order to determine the effect of the type of approach on developing complications, a logistic model was calculated with age, sex, BMI, ASA, smoking history, arterial hypertension, congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular accident, coronary disease, diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, arrhythmia, chronic kidney disease, tumor location, histology, stage, induction treatment, previous thoracic surgery, type of resection, surgeon experience with VATS, ppoFEV1 and ppoDLCO variable as confounders. All variables included in the model were selected according to clinical relevance. Following the recommendations, we used a caliper width equal to 0.2 of the standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score of this model taking into account total imputed data.13

Propensity score matching (1:1) was constructed using the STATA (College Station, TX) psmatch2 package in each of the imputed data sets.

To estimate the effect of the approach on morbidity, a random effects logistic model and a random effects linear model were used in matched patients, as appropriate. The models were adjusted for those variables with a standardized difference greater than 10%. The estimation of the effect of the approach in each of the 10 imputed samples was combined using Rubin’s rule. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

For the sensitivity analysis, we performed a logistic model using the inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW), calculated as 1/(1-p) for patients who underwent thoracotomy and 1/p for patients who underwent VATS.

ResultsA total of 2981 patients were finally included in the study: VATS was the initial approach in 2165 patients (72.6%), representing the treatment group in the ITT analysis. However, 276 cases (9.2%) were converted to thoracotomy; therefore, the VATSG in the treatment analysis consisted of 1889 (63%) patients. Patient baseline characteristics are given in Table 1.

Distribution of baseline characteristics of patients included before propensity-score matching.

| Variables | Treatment analysis | ITT analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TG | VATSG | Sd | TG | VATSG | Sd | Missing (%) | |

| n = 1092 | n = 1889 | n = 816 | n = 2165 | ||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 64.7 (10.3) | 65.4 (9.8) | 0.221 | 64.3 (10.3) | 65.5 (9.9) | 0.378 | 0 (0.0) |

| Gender | 1 (<0.1) | ||||||

| Male | 781 (71.6) | 1251 (66.2) | [Reference] | 568 (69.7) | 1464 (67.6) | [Reference] | |

| Female | 310 (28.4) | 638 (33.8) | 0.117 | 247 (30.3) | 701 (32.4) | 0.045 | |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 27.1 (4.7) | 26.9 (4.6) | −0.093 | 26.7 (4.6) | 27.0 (4.6) | 0.140 | 65 (2.2) |

| ASA | 6 (0.2) | ||||||

| I | 17 (1.6) | 51 (2.7) | [Reference] | 15 (1.8) | 53 (2.5) | [Reference] | |

| II | 432 (39.7) | 833 (44.2) | 0.091 | 320 (39.4) | 945 (43.7) | 0.087 | |

| III | 610 (56.0) | 966 (51.2) | −0.096 | 455 (56.0) | 1121 (51.9) | −0.082 | |

| IV | 30 (2.7) | 36 (1.9) | −0.053 | 23 (2.8) | 43 (2.0) | −0.052 | |

| History of smoking | 893 (81.8) | 1537 (81.4) | −0.010 | 660 (83.5) | 1770 (82.9) | −0.016 | 57 (1.9) |

| Hypertension | 477 (3.7) | 862 (45.6) | 1.113 | 345 (42.3) | 994 (46.0) | 0.075 | 3 (0.1) |

| Congestive cardiac failure | 31 (2.8) | 41 (2.2) | −0.038 | 17 (2.1) | 55 (2.5) | 0.027 | 0 (0.0) |

| Coronary artery disease | 98 (9.0) | 175 (9.3) | 0.010 | 65 (8.0) | 208 (9.6) | 0.057 | 0 (0.0) |

| Stroke | 58 (5.3) | 95 (5.0) | −0.014 | 44 (5.4) | 109 (5.0) | −0.018 | 0 (0.0) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1 (<0.1) | ||||||

| No | 879 (80.5) | 1557 (82.4) | [Reference] | 663 (81.3) | 1773 (81.9) | [Reference] | |

| Type I | 24 (2.2) | 24 (1.3) | −0.069 | 17 (2.1) | 31 (1.4) | −0.053 | |

| Type II | 188 (17.2) | 308 (16.3) | −0.024 | 135 (16.6) | 361 (16.7) | 0.003 | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 104 (9.5) | 171 (9.1) | −0.014 | 81 (9.9) | 194 (9.0) | −0.031 | 1 (<0.1) |

| Arrhythmia | 93 (8.5) | 148 (7.8) | −0.026 | 59 (7.2) | 182 (8.4) | 0.045 | 0 (0.0) |

| Chronic renal failure | 27 (2.5) | 55 (2.9) | 0.025 | 20 (2.5) | 62 (2.9) | 0.025 | 0 (0.0) |

| Tumor location | 413 (13.8) | ||||||

| Central | 427 (39.1) | 404 (21.4) | [Reference] | 347 (49.6) | 484 (25.9) | [Reference] | |

| Peripheric | 514 (47.1) | 1223 (64.7) | 0.360 | 353 (50.4) | 1384 (74.1) | 0.504 | |

| Histology | 421 (14.1) | ||||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 493 (45.2) | 997 (52.8) | [Reference] | 365 (52.5) | 1125 (60.3) | [Reference] | |

| Squamous cell | 298 (27.3) | 412 (21.8) | −0.128 | 225 (32.4) | 485 (26.0) | −0.141 | |

| Others | 144 (13.2) | 216 (11.4) | −0.055 | 105 (15.1) | 255 (13.7) | −0.040 | |

| Stage | 503 (16.9) | ||||||

| I | 450 (41.2) | 1110 (58.8) | [Reference] | 305 (45.9) | 1255 (69.2) | [Reference] | |

| Others | 449 (41.1) | 469 (24.8) | −0.352 | 359 (54.1) | 559 (30.8) | −0.485 | |

| Induction treatment | 93 (8.5) | 67 (3.6) | −0.207 | 81 (9.9) | 79 (3.6) | −0.253 | 0 (0.0) |

| Previous thoracic surgery | 102 (9.3) | 89 (4.7) | −0.181 | 84 (10.3) | 107 (4.9) | −0.205 | 0 (0.0) |

| Surgeon VATS experience | 378 (34.6) | 1313 (69.5) | 0.746 | 247 (30.3) | 1444 (66.7) | 0.782 | 0 (0.0) |

| Type of resection | 0 (0.0) | ||||||

| Lobectomy | 1019 (93.3) | 1733 (91.7) | 0.099 | 763 (93.5) | 1989 (91.9) | [Reference] | |

| Segmentectomy | 73 (6.7) | 156 (8.3) | 0.061 | 53 (6.5) | 176 (8.1) | 0.062 | |

| ppoFEV1, mean (SD) | 69.3 (16.4) | 74.0 (17.8) | 1.137 | 68.9 (16.3) | 73.5 (17.7) | 1.578 | 38 (1.3) |

| ppoDLCO, mean (SD) | 65.7 (17.9) | 68.0 (18.0) | 0.543 | 66.0 (17.9) | 67.6 (18.0) | 0.534 | 486 (16.3) |

All results are expressed as n (%) except where otherwise indicated. ITT, intention to treat; TG, thoracotomy group; VATSG, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery group; Sd, standardized difference; SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists risk scale; ppoFEV1, predicted postoperative forced expiratory volume in one second; ppoDLCO, predicted postoperative lung diffusion capacity.

After the imputation of missing data and performed the propensity score matching of patients, we obtained a mean of 804 patients matched (range 794–815) in the treatment analysis, and a mean of 541 patients matched in the ITT analysis (range 539–545). The baseline characteristics of the matched patients are shown in Table 2.

Distribution of baseline patient characteristics included after propensity-score matching.

| Variables | Treatment analysis | ITT analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TG | VATSG | Sd | TG | VATSG | Sd | |

| n = 804 | n = 804 | n = 541 | n = 541 | |||

| Age, mean (SD) | 64.7 (10.3) | 65.4 (9.8) | −0.8 | 65.0 (10.1) | 64.8 (9.6) | −0.064 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 565 (70.3) | 573 (71.3) | [Reference] | 378 (69.9) | 381 (70.4) | [Reference] |

| Female | 239 (29.7) | 231 (28.7) | −2.2 | 163 (30.1) | 160 (29.6) | −0.011 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 27.1 (4.7) | 26.9 (4.6) | −1.7 | 26.8 (4.6) | 26.5 (4.6) | −0.140 |

| ASA | ||||||

| I | 15 (1.9) | 12 (1.5) | [Reference] | 10 (1.8) | 9 (1.7) | [Reference] |

| II | 335 (41.7) | 336 (41.8) | 0.3 | 212 (39.2) | 192 (35.5) | −0.077 |

| III | 433 (53.9) | 432 (53.7) | −0.2 | 303 (56.0) | 325 (60.1) | 0.083 |

| IV | 21 (2.6) | 24 (3.0) | 2.5 | 16 (3.0) | 15 (2.8) | −0.012 |

| History of smoking | 669 (83.2) | 676 (84.1) | 2.3 | 472 (87.2) | 473 (87.4) | 0.006 |

| Hypertension | 359 (44.6) | 369 (45.9) | 2.5 | 242 (44.7) | 236 (43.6) | −0.022 |

| Congestive cardiac failure | 24 (3.0) | 24 (3.0) | 0 | 13 (2.4) | 9 (1.7) | −0.049 |

| Coronary artery disease | 69 (8.6) | 73 (9.1) | 1.7 | 52 (9.6) | 43 (7.9) | −0.060 |

| Stroke | 46 (5.7) | 42 (5.2) | −2.2 | 30 (5.5) | 31 (5.7) | 0.009 |

| Diabetes mellitus | ||||||

| No | 654 (81.3) | 641 (79.7) | [Reference] | 432 (79.9) | 431 (79.7) | [Reference] |

| Type I | 13 (1.6) | 11 (1.4) | 1 | 8 (1.5) | 9 (1.7) | 0.016 |

| Type II | 137 (17.0) | 149 (18.5) | 4 | 101 (18.7) | 101 (18.7) | 0.000 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 77 (9.6) | 80 (9.9) | 1.3 | 63 (11.6) | 65 (12.0) | 0.012 |

| Arrhythmia | 65 (8.1) | 68 (8.5) | 1.4 | 44 (8.1) | 39 (7.2) | −0.034 |

| Chronic renal failure | 23 (2.9) | 20 (2.5) | −2.3 | 15 (2.8) | 18 (3.3) | 0.029 |

| Tumor location | ||||||

| Central | 295 (36.7) | 316 (39.3) | [Reference] | 235 (43.4) | 267 (49.4) | [Reference] |

| Peripheric | 509 (63.3) | 488 (60.7) | −5.5 | 306 (56.6) | 274 (50.6) | −0.121 |

| Histology | ||||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 442 (55.0) | 444 (55.2) | [Reference] | 299 (55.3) | 279 (51.6) | [Reference] |

| Squamous cell | 229 (28.5) | 240 (29.8) | 3.1 | 164 (30.3) | 176 (32.5) | 0.047 |

| Others | 133 (16.5) | 120 (14.9) | −4.5 | 78 (14.4) | 86 (15.9) | 0.042 |

| Stage | ||||||

| I | 492 (61.19) | 457 (56.8) | [Reference] | 287 (53.0) | 268 (49.5) | [Reference] |

| Others | 312 (38.8) | 347 (43.2) | 9.1 | 254 (47.0) | 273 (50.5) | 0.070 |

| Induction treatment | 41 (5.1) | 52 (6.5) | 5.8 | 41 (7.6) | 53 (9.8) | 0.078 |

| Previous thoracic surgery | 55 (6.8) | 69 (8.6) | 6.9 | 37 (6.8) | 38 (7.0) | 0.008 |

| Surgeon VATS experience | 360 (44.8) | 263 (32.7) | −25.8 | 204 (37.7) | 137 (25.3) | −0.269 |

| Type of resection | ||||||

| Lobectomy | 745 (92.7) | 749 (93.2) | [Reference] | 507 (93.7) | 514 (95.0) | [Reference] |

| Segmentectomy | 59 (7.3) | 55 (6.8) | −1.9 | 34 (6.3) | 27 (5.0) | −0.056 |

| ppoFEV1, mean (SD) | 69.4 (16.4) | 73.9 (17.8) | −5.6 | 69.7 (15.7) | 67.7 (16.4) | −0.499 |

| ppoDLCO, mean (SD) | 65.8 (17.9) | 68.0 (18.1) | −1.2 | 65.6 (17.4) | 64.6 (18.7) | −0.235 |

All results are expressed as n (%) except where otherwise indicated. ITT, intention to treat; Sd: standardized difference; TG, thoracotomy group; VATSG, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery group; SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists risk scale; ppoFEV1, predicted postoperative forced expiratory volume in one second; ppoDLCO, predicted postoperative lung diffusion capacity.

Postoperative outcomes of the unmatched cohort of patients in both analyses can be found in Table 3.

Postoperative outcomes (not matched).

| Treatment analysis | ITT analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TG | VATSG | OR | TG | VATSG | OR | |

| n = 1092 | n = 1889 | [95% CI] | n = 816 | n = 2165 | [95% CI] | |

| Any complication | 362 (33.1) | 447 (23.7) | 0.63 [0.60; 0.66] | 251 (30.8) | 524 (24.2) | 0.72 [0.60; 0.86] |

| Respiratory complication | 170 (15.6) | 157 (8.3) | 0.492 [0.458; 0.527] | 118 (14.5) | 209 (9.7) | 0.63 [0.50; 0.80] |

| Prolongation of intubation | 3 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.1) | ||

| Reintubation | 25 (2.3) | 13 (0.7) | 16 (2.0) | 22 (1.0) | ||

| Atelectasis | 55 (5.0) | 51 (2.7) | 36 (4.4) | 70 (3.2) | ||

| Pneumothorax or pleural effusion | 26 (2.4) | 39 (2.1) | 19 (2.3) | 46 (2.1) | ||

| Pneumonia | 70 (6.4) | 53 (2.8) | 52 (6.4) | 71 (3.3) | ||

| ARDS | 11 (1.0) | 11 (0.6) | 6 (0.7) | 16 (0.7) | ||

| Pulmonary embolism | 5 (0.5) | 3 (0.2) | 4 (0.5) | 4 (0.2) | ||

| Other respiratory morbidity | 36 (3.3) | 25 (1.3) | 22 (2.7) | 39 (1.8) | ||

| Cardiovascular complication | 87 (8.0) | 74 (3.9) | 0.47 [0.43; 0.52] | 57 (7.0) | 104 (4.8) | 0.67 [0.48; 0.94] |

| Arrythmia | 62 (5.7) | 49 (2.6) | 45 (5.5) | 66 (3.0) | ||

| Acute heart failure | 6 (0.5) | 9 (0.5) | 2 (0.2) | 13 (0.6) | ||

| Acute coronary events | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.1) | ||

| Stroke | 2 (0.2) | 3 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.2) | ||

| Deep venous thrombosis | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | ||

| Postoperative blood transfusion | 19 (1.7) | 11 (0.6) | 11 (1.3) | 19 (0.9) | ||

| Other cardiovascular morbidity | 8 (0.7) | 8 (0.4) | 5 (0.6) | 11 (0.5) | ||

| Surgical complication | 184 (16.8) | 267 (14.1) | 0.81 [0.76, 0.86] | 139 (17.0) | 312 (14.4) | 0.82 [0.66; 1.02] |

| Prolonged air leak | 146 (13.4) | 236 (12.5) | 112 (13.7) | 270 (12.5) | ||

| Bronchopleural fistula | 9 (0.8) | 2 (0.1) | 5 (0.6) | 6 (0.3) | ||

| Empyema | 16 (1.5) | 8 (0.4) | 13 (1.6) | 11 (0.5) | ||

| Chylothorax | 5 (0.5) | 4 (0.2) | 5 (0.6) | 4 (0.2) | ||

| Wound infection | 19 (1.7) | 16 (0.8) | 12 (1.5) | 23 (1.1) | ||

| Reoperation for bleeding | 14 (1.3) | 17 (0.9) | 11 (1.3) | 20 (0.9) | ||

| Reoperations | 32 (2.9) | 48 (2.5) | 0.86 [0.75, 0.99] | 21 (2.6) | 59 (2.7) | 1.06 [0.64; 1.76] |

| Readmissions | 85 (8.4) | 88 (4.9) | 0.55 [0.52, 0.61] | 66 (8.7) | 107 (5.2) | 0.57 [0.42; 0.79] |

| Hospital length of stay (days), mean (SD) | 7.6 (7.4) | 5.6 (5.2) | −2.25 [−2.39; −2.11]* | 6.0 (4.0; 8.0) | 4.0 (3.0; 7.0) | −1.81 [−2.31; −1.31]* |

All results are expressed as n (%) except where otherwise indicated. TG, thoracotomy group; VATSG, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery group; SD, standard deviation.

Analysis of the propensity-matched groups in the treatment analysis for postoperative outcomes demonstrated that the VATSG was significantly associated with fewer overall complications than the TG OR 0.680 [95%CI 0.616, 0.750]). A significant association was also observed with fewer respiratory (OR 0.571 [0.529, 0.616]) cardiovascular (OR 0.529 [0.478, 0.609]) and surgical (OR 0.875 [0.802, 0.955]) complications. In addition, statistically significant differences have been observed in readmissions (OR 0.669 [0.578, 0.775]) and a reduction of hospital length of stay (Coef. −1.741 ([−2.073, −1.410]) in favor of the VATSG. Fewer specific complications have been observed in VATSG patients: reintubation, pneumonia, atelectasis, ARDS, pneumothorax or pleural effusion, pulmonary thromboembolism, arrhythmia, stroke, acute coronary events, need for postoperative blood transfusion, prolonged air leak, empyema, bronchopleural fistula, chylothorax, and wound infection (Table 4).

Postoperative outcomes (matched).

| Treatment analysis | ITT analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TG | VATSG | OR | TG | VATSG | OR | |

| n = 804 | n = 804 | [95% CI] | n = 541 | n = 541 | [95% CI] | |

| Any complication | 262 (32.6) | 196 (24.4) | 0.68 [0.62; 0.75] | 160 (29.6) | 147 (27.2) | 0.76 [0.54; 0.99] |

| Respiratory complication | 122 (15.2) | 72 (9.0) | 0.57 [0.53; 0.62] | 70 (12.9) | 66 (12.2) | 0.79 [0.47; 1.11] |

| Prolongation of intubation | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | ||

| Reintubation | 17 (2.1) | 7 (0.9) | 7 (1.3) | 9 (1.7) | ||

| Atelectasis | 39 (4.8) | 21 (2.6) | 25 (4.6) | 19 (3.5) | ||

| Pneumothorax or pleural effusion | 22 (2.7) | 19 (2.4) | 11 (2.0) | 11 (2.0) | ||

| Pneumonia | 45 (5.6) | 25 (3.1) | 24 (4.4) | 23 (4.3) | ||

| ARDS | 7 (0.9) | 5 (0.6) | 5 (0.9) | 2 (0.4) | ||

| Pulmonary embolism | 4 (0.5) | 3 (0.4) | 3 (0.6) | 3 (0.6) | ||

| Other respiratory morbidity | 27 (3.4) | 11 (1.4) | 15 (2.8) | 15 (2.8) | ||

| Cardiovascular complication | 66 (8.2) | 35 (4.3) | 0.53 [0.48; 0.61] | 34 (6.3) | 28 (5.2) | 0.70 [0.29; 1.11] |

| Arrythmia | 47 (5.8) | 24 (3.0) | 29 (5.4) | 16 (3.0) | ||

| Acute heart failure | 4 (0.5) | 4 (0.5) | 2 (0.4) | 3 (0.6) | ||

| Acute coronary events | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | ||

| Stroke | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) | ||

| Deep venous thrombosis | 0 (0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | ||

| Postoperative blood transfusion | 14 (1.7) | 4 (0.5) | 7 (1.3) | 6 (1.1) | ||

| Other cardiovascular morbidity | 6 (0.7) | 4 (0.5) | 2 (0.4) | 3 (0.6) | ||

| Surgical complication | 132 (16.4) | 117 (14.5) | 0.86 [0.80; 0.96] | 89 (16.5) | 91 (16.8) | 0.91 [0.60; 1.22] |

| Prolonged air leak | 105 (13.1) | 102 (12.7) | 75 (13.9) | 75 (13.9) | ||

| Bronchopleural fistula | 9 (1.1) | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.4) | ||

| Empyema | 13 (1.6) | 6 (0.7) | 6 (1.1) | 4 (0.7) | ||

| Chylothorax | 4 (0.5) | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.4) | ||

| Wound infection | 16 (2.0) | 8 (1.0) | 5 (0.9) | 11 (2.0) | ||

| Reoperation for bleeding | 8 (1.0) | 7 (0.9) | 8 (1.5) | 4 (0.7) | ||

| Reoperations | 22 (2.7) | 18 (2.2) | 0.96 [0.72; 1.30] | 13 (2.4) | 12 (2.2) | 0.87 [0.09; 1.64] |

| Readmissions | 59 (7.9) | 43 (5.6) | 0.67 [0.58; 0.78] | 48 (9.4) | 35 (6.8) | 0.68 [0.34; 1.03] |

| Hospital length of stay (days), mean (SD) | 7.8 (7.6) | 6.0 (5.6) | −1.74 [−2.07; −1.41] | 6.0 [4.0; 8.0] | 5.0 [4.0; 7.0] | −0.03 [−0.19; 0.13]* |

All results are expressed as n (%) except where otherwise indicated. TG, thoracotomy group; VATSG, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery group; SD, standard deviation.

Analysis of the propensity-matched groups in the ITT analysis (which includes conversions in VATSG) showed statistically significant differences in overall complications (OR 0.76 [0.54–0.99], whereas non-significant associations were observed in respiratory (OR 0.79 [0.47; 1.11], cardiovascular (OR 0.70 [0.29; 1.11]) and surgical complications (0.91 [0.60; 1.22]), either in reoperations (OR 0.87 [0.09; 1.64], readmissions (OR 0.68 [0.34; 1.03]) or hospital length of stay (Coef. −0.03 [−0.19; 0.13]). Similar rates of specific complications have been observed in both groups excluding atelectasis and arrythmia, which were higher in the TG.

The results of the sensitivity analysis of the logistic model weighted by IPTW are consistent with propensity score results: for the overall complications in the treatment analysis, it demonstrated that VATS was associated with significantly lower complications (OR 0.629 [95% CI 0.617–0.641]); the sensitivity analysis for overall complications in the ITT analysis showed a non-significant association in favor of VATS (OR 0.83 [0.61–1.05]).

The baseline characteristics and postoperative outcomes of converted procedures are shown in Table 5.

Baseline characteristics and postoperative outcomes of converted from VATS to open patients.

| Converted from VATS to open | |

|---|---|

| n = 276 | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 65.90 (10.26) |

| ASA III | 56.16 (56.16%) |

| Central tumor location | 80 (33.20%) |

| Stage I | 145 (61%) |

| Induction treatment | 12 (4.35%) |

| VATS surgeon’s experience | 131 (47.46%) |

| ppoFEV1, mean (SD) | 79.46 (16.41) |

| ppoDLCO, mean (SD) | 64.91 (17.80) |

| Any complication | 101 (36.59%) |

| Respiratory complication | 79 (28.62%) |

| Cardiovascular complication | 30 (10.87%) |

| Reoperations | 11 (4%) |

| Readmissions | 19 (7.60%) |

| Hospital length of stay (days), mean (SD) | 8.21 (7.35) |

All results are expressed as n (%) except where otherwise indicated. BMI, body mass index; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists risk scale; ppoFEV1, predicted postoperative forced expiratory volume in one second; ppoDLCO, predicted postoperative lung diffusion capacity.

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

DiscussionFor many years, the standard approach for anatomical lung resections was thoracotomy. In the 90s, minimally invasive surgery was adapted for lobectomies, and in 1991 the first VATS lobectomy was reported.14 During the last 3 decades, the use of VATS surgery has been increasing worldwide; however, VATS rates vary among different countries and institutions. In Spain, some studies describe the absence of VATS in the 1990s.15 As of 2010, approximately 30% of lobectomies were performed by thoracoscopy.16,17 In our study, the percentage of thoracoscopic resections almost doubled, which indicates the fast implementation of VATS in our country in the last decade.

Since first reports of VATS lobectomies, a great experience has been accumulated. Published data include large database analyses comparing with unmatched comparisons, meta-analyses, propensity score studies, outcome studies with results adjusted for other factors and some small, randomized studies. After randomized studies, propensity score analysis may provide some of the best evidence. Currently, there are no studies in the published literature about the postoperative complications of VATS lobectomies versus open procedures using a large database in Spain, which can reflect current practice in this country compared to other European countries and the rest of the world.

The GE-VATS database used in our study guarantees excellent data quality,9 due to the few missing data and the auditing systems implemented. Recently, several studies have been published with this database related to VATS postoperative outcomes.18–23

To our knowledge, our study is the first propensity score morbidity analysis of major lung resections that includes more patients operated by VATS than by thoracotomy (73% vs 27%). Among the studies published to date comparing VATS versus open surgery using the propensity score, ours includes more current patient data (2016–2018) and is the only study that includes surgeon experience as one of the major deciding factors for the selection of the surgical approach.

Analyzing the propensity-matched groups for postoperative outcomes in the treatment analysis, we have shown that major VATS resections are significantly associated with lower postoperative morbidity compared to thoracotomy, with a lower overall complication rate (24.4% vs 32.6%) and lower rates of cardiovascular (35% vs 66%) and respiratory (9.0% vs 15.2%) complications. In addition, fewer specific respiratory and cardiovascular complications have been observed in our VATSG patients, including reintubation, pneumonia, atelectasis, ARDS, arrhythmia, stroke and need for postoperative blood transfusion.

VATS resections also had a significantly lower surgical complication rate (14.4% vs 16.4%), especially emphasizing the higher incidence of bronchopleural fistula (0.2% vs 1.1%), lower rate of readmissions and shorter length of hospital stay in the treatment analysis.

However, this protective effect of VATS lost statistical significance when an ITT was performed, excluding the overall complication rate. When specific respiratory and cardiovascular complication rates were analyzed, lower rates of multiple complications in favor of VATSG in the treatment analysis became less noteworthy after performing the ITT analysis.

Our results in the treatment analysis coincide with other previous reports using international and national registries with similar methodology,3,6,24,25 where information about conversion from VATS to open surgery due to anatomic constraints or complications is not registered. The fact that ITT analysis could not be performed may inherently bias results against open surgery or in favor of VATS lobectomies, reporting better outcomes in the latter approach.

Intention-to-treat analysis is the gold standard for randomized clinical trials as it maintains prognostic balance. In recent years, ITT has been considered to show the real impact of VATS lobectomy and to provide more realistic findings.26 Laursen et al.27 found that patients who underwent VATS were less likely to have complications, compared with patients operated by thoracotomy, even performing an intention-to-treat analysis. These results are not consistent with ours, and this study was not matched.

In contrast, our findings are consistent with previously published results about the effect of VATS on mortality by our group.28 Recuero-Díaz et al. showed a 65%–70% reduction in mortality in patients after anatomical lung resection conducted with VATS, which decreased to the extent that statistically non-significant differences were obtained when an ITT analysis was performed.

Although the aim of our study was not to examine the outcomes of converted procedures, our results would indirectly support a negative effect associated with conversion.

The results must be interpreted carefully because of the differences observed according to the analysis performed and the differences among the published literature.

Although data collection was performed prospectively, the decision to perform each approach was not randomized and was left to the discretion of the surgeon. Also, this study includes a large number of centers, and case distribution is not homogeneous among them. In order to reduce this bias, we decided to include surgeon experience with VATS in the propensity analysis.

However, although the results of this study do not reach level 1 of evidence obtained from randomized trials, the propensity score used, treatment and ITT analyses, large patient cohort and characteristics of the database analyzed, all improve the quality of the evidence, making this study a good contribution to the literature.

In conclusion, in the GE-VATS cohort, VATS anatomic lung resections were associated with a lower incidence of postoperative complications, lower rate of readmissions and shorter hospital stay compared to thoracotomy. However, when a secondary analysis including converted procedures in the VATS group (intention-to treat) was performed, the differences between approaches lost statistical significance. In light of this, multicenter randomized trial results are still needed to confirm our findings.

Sources of fundingAll costs related to the start-up and maintenance of the GE-VATS database were covered by Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson. The authors had research freedom and full control of the study design, the methods used, the outcomes and results, the data analysis, and the production of the written report. GE-VATS has received a research grant from the Spanish Society of Thoracic Surgery in 2015.

Conflict of interestNone declared.

To all members of the GE-VATS group: Borja Aguinagalde Valiente, Sergio Amor Alonso, Miguel Jesús Arrarás Martínez, Ana Isabel Blanco Orozco, Marc Boada Collado, Isabel Cal Vázquez, Sergi Call Caja, Ángel Cilleruelo Ramos, Miguel Congregado Loscertales, Silvana Crowley Carrasco, Raúl Embún Flor, Elena Fernández Martín, Juan José Fibla Alfara, Santiago García Barajas, María Dolores García Jiménez, Jose María García Prim, Jose Alberto García Salcedo, Carlos Fernando Giraldo Ospina, María Teresa Gómez Hernández, Juan José Guelbenzu Zazpe, Jorge Hernández Ferrández, Florentino Hernando Trancho, Jennifer D. Illana Wolf, Alberto Jauregui Abularach, Marcelo F. Jiménez López, Unai Jiménez, Cipriano López García, Iker López Sanz, Elisabeth Martínez Téllez, Lucía Milla Collado, Roberto Mongil Poce, Francisco Javier Moradiellos Díez, Ramón Moreno Balsalobre, Sergio B. Moreno Merino, Carme Obiols, Florencio Quero Valenzuela, María Elena Ramírez Gil, Ricard Ramos Izquierdo, José Luis Recuero Díaz, Eduardo Rivo Vazquez, Alberto Rodríguez Fuster, Rafael Rojo Marcos, Iñigo Royo Crespo, David Sánchez Lorente, Laura Sánchez Moreno, Julio Sesma Romero, Carlos Simón Adiego, Juan Carlos Trujillo-Reyes.