Patients with giant hernias with loss of domain require proper planning of surgical repair, because of the high associated comorbidity. The progressive preoperative pneumoperitoneum technique described by Goñi Moreno allows a more physiological adaptation of the patient and the abdominal cavity to the reinstatement of the viscera to the abdomen, enabling adequate surgical repair. The objective of this study was to analyze our experience in the treatment of this type of hernia.

Materials and methodsWe carried out a retrospective study that included 11 patients with major abdominal wall defects and loss of domain who were treated with this technique in 2 centers between 2005 and 2010.

ResultsEight patients had abdominal hernias and 3 had inguinal hernias. The average insufflation time was 2 weeks and the total amount of air was between 6.6 and 18l. In 2 patients who showed pulmonary disease decompensation, insufflation had to be temporarily postponed. A further 2 patients had subcutaneous emphysema during the last few days of insufflation, which resolved spontaneously without sequelae. The open mesh repair technique was used in ventral hernias and the preperitoneal technique in all inguinal hernias. There was one recurrence during the 1-year follow-up.

ConclusionsGoñi Moreno's technique remains safe to prepare patients with giant hernias with loss of domain. This procedure can reduce the morbidity caused by the increase in abdominal pressure after abdominal wall repair.

Los pacientes con hernias gigantes con pérdida de domicilio requieren una adecuada planificación de la reparación quirúrgica, porque en la mayoría se asocia una elevada comorbilidad. La técnica del neumoperitoneo progresivo preoperatorio descrita por Goñi Moreno permite una adaptación más fisiológica del paciente y de la cavidad abdominal al reintegro de las vísceras al abdomen, lo que permite una reparación quirúrgica adecuada. El objetivo es analizar nuestra experiencia en el tratamiento de este tipo de hernias.

Materiales y métodosEstudio retrospectivo en que se analizan 11 pacientes portadores de grandes defectos de pared abdominal, con pérdida de domicilio, tratados mediante dicha técnica, en 2 centros entre los años 2005 y 2010.

ResultadosDel total, ocho pacientes presentaban eventraciones abdominales y los otros 3 tenían hernias inguinales. El tiempo medio de insuflación fue de 2 semanas y la cantidad total de aire varió entre 6,6 y 18 l. Dos pacientes presentaron descompensación de su enfermedad pulmonar y se debió posponer temporalmente la insuflación. Otros 2 presentaron enfisema subcutáneo durante los últimos días de insuflación, que se resolvió espontáneamente y sin secuelas. Se utilizaron técnicas de eventroplastia abierta con malla en los 8 casos de eventraciones y técnica preperitoneal para las hernias inguinoescrotales. En el seguimiento posterior se objetivó un caso de recidiva.

ConclusionesLa técnica de Goñi Moreno sigue siendo una técnica segura para preparar a los pacientes con hernias gigantes con pérdida de domicilio, pues consigue reducir la morbilidad ocasionada por la hiperpresión abdominal tras la reparación de la pared abdominal.

Patients with giant hernias and loss of domain have chronic defects of the abdominal wall, which begin to grow and slowly and progressively alter the normal physiology of the abdominal wall and all adjacent systems. The repair of these defects can lead to several serious pathophysiological problems such as abdominal compartment syndrome, produced by sudden introduction of the herniated abdominal contents into a cavity that has already chronically decreased in size and does not have enough space to accommodate this content. It then produces acute respiratory compromise secondary to the sudden increase in intra-abdominal pressure. Hence, adequate preparation is important, including the progressive re-adaptation of all systems to the reintroduction of the visceral content and abdominal wall reconstruction.1,2

In 1940, Goñi Moreno1 published for the first time his experience with preoperative progressive pneumoperitoneum for the treatment of large hernias. Since then, this technique has been modified and improved and is currently used throughout the world with positive results.2 However, the series found in the literature are still relatively small, making these results difficult to extrapolate to large patient populations.

The aim of this paper is to present our experience in the preparation of patients with giant hernias with loss of domain, using preoperative progressive pneumoperitoneum.

Patients and MethodsBetween 2005 and 2010, 11 patients were treated in our center with giant abdominal wall defects with loss of domain. The patients included 8 men and 3 women, with a mean age of 63 (52–86 years). Eight patients had abdominal incisional hernias and 3 presented with giant scrotal hernias. 90% of all hernias were recurrent and had had previous local complications such as infection or wound dehiscence. The most important comorbidity found in all patients was obesity, with a mean body mass index (BMI) of 33.5 (30–42). Other common comorbidities were chronic obstructive bronchitis, diabetes and hypertension.

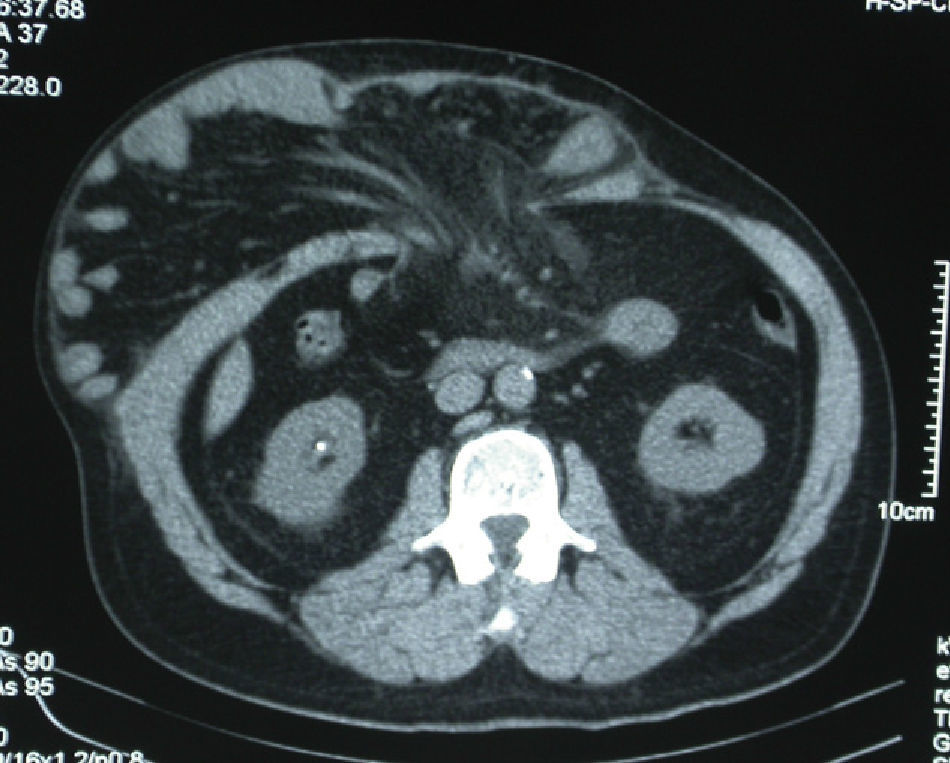

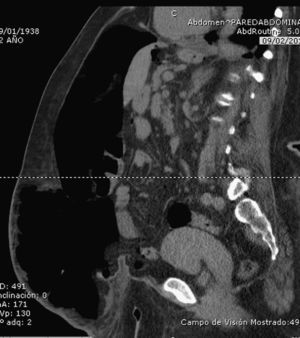

Technically, abdominal hernia or incisional hernia with loss of domain was defined as having more than 50% of the abdominal cavity contents outside the abdomen (Fig. 1). In most cases, this was determined with a preoperative abdominal CT scan (Fig. 2). Once they had been selected, the patients were referred for pre-anesthetic assessment and scheduled for hospitalization prior to the surgical intervention.

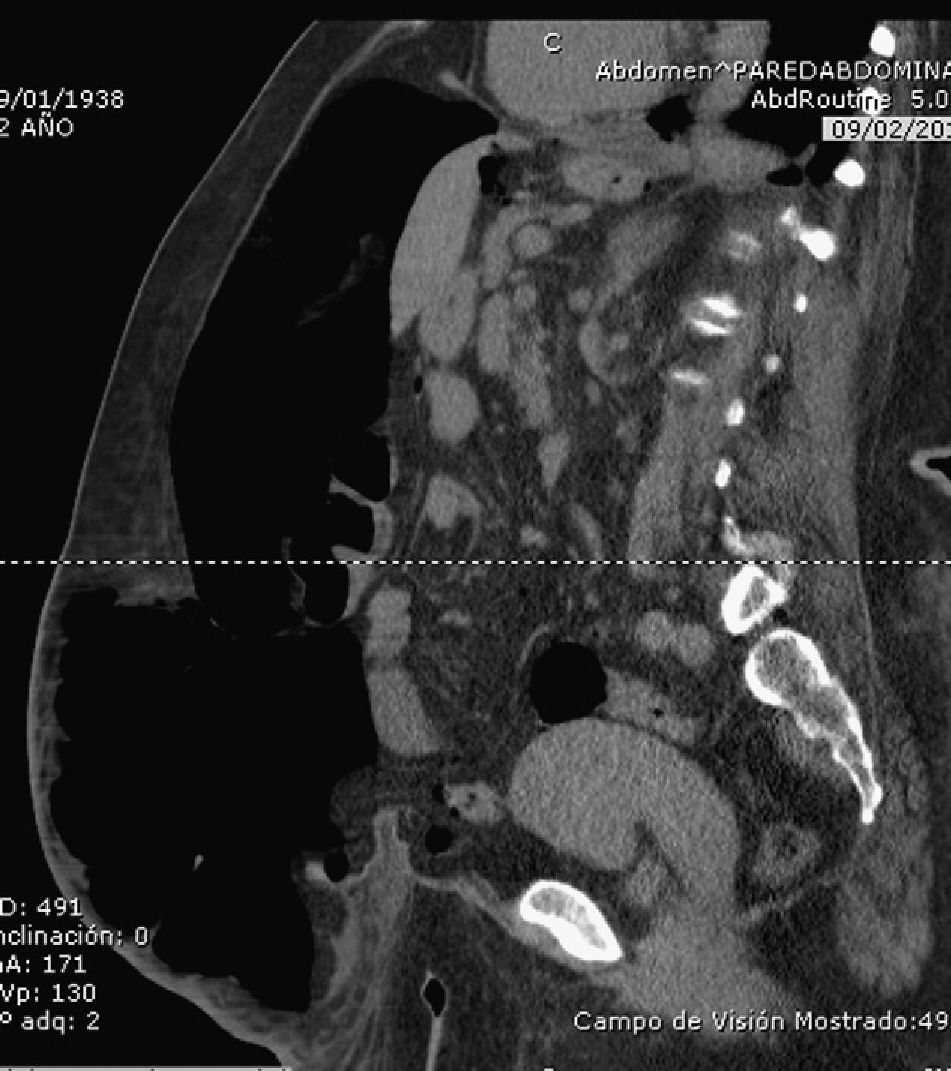

The technique involved the initial placement of a catheter within the abdominal cavity. This procedure was performed in the operating room under local anesthesia and sedation, with the initial creation of a small pneumoperitoneum with a Veress needle to insert the intraperitoneal catheter (Fig. 3) guided by either ultrasound or CT. All patients were previously admitted to the hospital and signed an informed consent form authorizing the pneumoperitoneum procedure and intervention. Immediately after the initial insertion of the catheter, the first dose of room air was injected through a device with a bacterial filter that was used daily for insufflation (double-lumen catheter similar to the one used in central lines).

In 6 patients, the insufflation catheter was inserted in the operating room. The other 5 patients underwent ultrasound- or CT-guided catheter placement. We performed an initial insufflation of between 0.5 and 1l of room air, depending on patient tolerance. Inflations were done over an average period of 15 days (8–24 days), introducing an air volume of between 6.6 and 18l.

During daily insufflation, the patient remained in bed in supine decubitus and the process was monitored clinically. Patients were also asked about the appearance of symptoms such as abdominal pain, difficulty breathing or nausea. Between 0.9 and 1.5l of air were insufflated daily. All patients remained hospitalized during the procedure and received prophylactic anticoagulant therapy.

After 2 weeks of insufflation, the abdominal wall was examined by evaluating the muscle tension exhibited on the side of the abdomen in order to verify that this was becoming sufficiently relaxed. In some cases, the patients underwent a control CT scan (Fig. 4), but this was not done systematically because the follow-up of the progression was mainly clinical. Patients were considered fit for surgery when the lateral abdominal musculature was completely distended.

We then proceeded with the surgical repair, which was planned according to the morphology of the defect of each patient. In all cases, prosthetic material was used.

Open hernioplasty was performed in 7 patients, with preaponeurotic placement (onlay) of polypropylene mesh in 6 cases, and intraperitoneal substitution mesh with preaponeurotic (onlay) reinforcement with bioabsorbable mesh used in one case. We performed the separation of anatomic components technique (SAC) in 2 cases. The preperitoneal hernioplasty technique with polypropylene mesh was used in the 3 patients with scrotal hernia. In one case, we performed laparoscopic hernia repair with PTFE mesh due to the presentation of a giant sack with >50% hernia content but a relatively small wall defect (<10cm).

Patients remained hospitalized until they recovered good tolerance to oral intake, had adequate pain control, the drains had been removed and the surgical wound could be treated on an outpatient basis. Postoperative follow-up was performed 30 days, three months, six months and one year later.

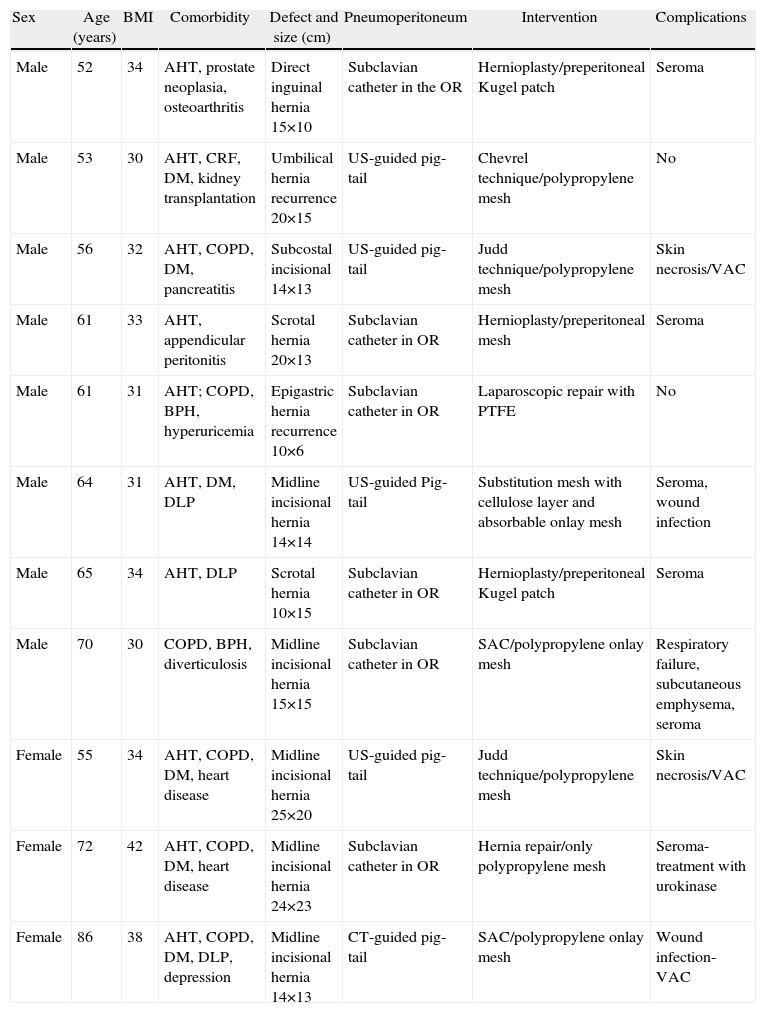

ResultsThe most important complications presented during the course of pneumoperitoneum were related to decompensation of chronic lung disease in 2 patients, in whom it was necessary to postpone the insufflations for one month and two weeks, respectively, to stabilize respiratory function. Subsequently, these patients were able to be operated on without incident. As a complication of the procedure, 2 patients presented subcutaneous emphysema during the last days of the insufflation, which resolved spontaneously with no consequences. The main postoperative complication was seroma, which presented in 10 patients; suture dehiscence requiring VAC therapy was seen in 4 patients (Table 1).

| Sex | Age (years) | BMI | Comorbidity | Defect and size (cm) | Pneumoperitoneum | Intervention | Complications |

| Male | 52 | 34 | AHT, prostate neoplasia, osteoarthritis | Direct inguinal hernia 15×10 | Subclavian catheter in the OR | Hernioplasty/preperitoneal Kugel patch | Seroma |

| Male | 53 | 30 | AHT, CRF, DM, kidney transplantation | Umbilical hernia recurrence 20×15 | US-guided pig-tail | Chevrel technique/polypropylene mesh | No |

| Male | 56 | 32 | AHT, COPD, DM, pancreatitis | Subcostal incisional 14×13 | US-guided pig-tail | Judd technique/polypropylene mesh | Skin necrosis/VAC |

| Male | 61 | 33 | AHT, appendicular peritonitis | Scrotal hernia 20×13 | Subclavian catheter in OR | Hernioplasty/preperitoneal mesh | Seroma |

| Male | 61 | 31 | AHT; COPD, BPH, hyperuricemia | Epigastric hernia recurrence 10×6 | Subclavian catheter in OR | Laparoscopic repair with PTFE | No |

| Male | 64 | 31 | AHT, DM, DLP | Midline incisional hernia 14×14 | US-guided Pig-tail | Substitution mesh with cellulose layer and absorbable onlay mesh | Seroma, wound infection |

| Male | 65 | 34 | AHT, DLP | Scrotal hernia 10×15 | Subclavian catheter in OR | Hernioplasty/preperitoneal Kugel patch | Seroma |

| Male | 70 | 30 | COPD, BPH, diverticulosis | Midline incisional hernia 15×15 | Subclavian catheter in OR | SAC/polypropylene onlay mesh | Respiratory failure, subcutaneous emphysema, seroma |

| Female | 55 | 34 | AHT, COPD, DM, heart disease | Midline incisional hernia 25×20 | US-guided pig-tail | Judd technique/polypropylene mesh | Skin necrosis/VAC |

| Female | 72 | 42 | AHT, COPD, DM, heart disease | Midline incisional hernia 24×23 | Subclavian catheter in OR | Hernia repair/only polypropylene mesh | Seroma-treatment with urokinase |

| Female | 86 | 38 | AHT, COPD, DM, DLP, depression | Midline incisional hernia 14×13 | CT-guided pig-tail | SAC/polypropylene onlay mesh | Wound infection-VAC |

DLP: dyslipidemia; DM: diabetes mellitus; US: ultrasound; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; BPH: benign prostatic hyperplasia; AHT: hypertension arterial; BMI: body mass index; CRF: chronic renal failure; PTFE: polytetrafluoroethylene; SAC: separation of anatomic components; CT: computed tomography; VAC: vacuum-assisted closure.

Mean postoperative hospital stay was 17.7 days (range: 6–60 days). In the outpatient follow-up, only one case of ventral hernia recurrence was registered 12 months after surgery.

DiscussionThe complex nature of patients with giant hernias of the abdominal wall has forced us better understand the pathophysiology of the readjustment of multiple organs and systems due to the lack of a functional abdominal cavity. This readjustment can lead to various complications (respiratory failure, abdominal visceral irrigation deficiency, etc.) when carrying out surgical correction that entails reintegrating the content into the abdomen while, at the same time, reconstructing the abdominal wall.

For many years, the progressive preoperative pneumoperitoneum technique described by Goñi Moreno in the 1940s1 has been used and improved for the treatment of these patients. While it is true that its use has not been generalized in most hospitals, specialized surgical teams that have incorporated this technique in the treatment of complex abdominal wall pathologies have reported good results with acceptable risk.2–13

Technically, the procedure has undergone some significant improvements, such as the use of a double-lumen catheter (like those used in central lines) for the inflation of the pneumoperitoneum.2,11 This eliminates the need for daily punctures as the initial technique described, with the added advantage of reduced incidence of infection at the puncture site. Recently, we have established the use of a pigtail catheter, which also has an antibacterial filter. In our most recent cases, ultrasound-guided placement of the catheters has replaced the earlier catheter insertion procedure done with a Veress needle.2,3 As for the pneumoperitoneum, we use room air because the CO2 and oxygen that were initially used in this technique1,8 are absorbed in the intraperitoneal space at a rate that is 4 times faster than room air.4

To control the inflation volume, some authors perform intraabdominal pressure measurements.2,5,9 In our case, we insufflated a daily volume of air that ranged between 0.9 and 1.5l, as limited by the tolerance of the patient or symptoms such as discomfort, pain or nausea, which directly correlate with increased abdominal pressure.1

After monitoring the abdominal circumference and respiratory function of patients, some authors insist that there is no benefit of pneumoperitoneum beyond 6–10 days of inflation.4 In our experience, the average number of days of insufflation was 15, with individual variability depending on the tolerance of each patient.

The Goñi Moreno groups ended inflations when the palpated abdominal flanks were sufficiently relaxed and prominent.1,4 It is generally considered that a patient who does not tolerate preoperative progressive insufflation well will also not tolerate the definitive surgical repair well.12

One of the additional effects of pneumoperitoneum is the increased length of the abdominal straight muscles as determined by topographical measurements on CT scans.6 This increase could facilitate fascial repair in giant ventral hernias with minimal-tension closure.

Most studies describe the use of progressive pneumoperitoneum for giant ventral hernia repair. However, in our experience and that of other authors,5,7,10 this technique can also be used to resolve giant inguinal and umbilical hernias, with good results. In all cases, we recommend using prosthetic materials.4

The complications described in this technique are mainly local, such as subcutaneous emphysema and abdominal wall infections. Serious complications are uncommon and related with baseline cardiopulmonary disease. In our series, we found a frequency of complications similar to those described in the literature, as well as a lower rate of recurrences in primary closures.4,5,13

Although there is no conclusive evidence in the literature for the treatment of patients with complex abdominal wall disease, if we look at the series published in the past 10 years,2,3,5,7,12 it seems that the technique described can be safely used in the hospital setting while providing better surgical outcomes than primary repair techniques.

ConclusionsAfter our experience in the use of preoperative progressive pneumoperitoneum, we believe that it is a safe and easy-to-perform technique that can complement complex ventral hernia repair techniques like SAC. It provides advantages in the preparation of patients with large abdominal wall defects and obtains good surgical results and multisystem adaptation of the patient.

With this article we want to join the efforts of different groups that specialize in the abdominal wall and share our experience in using this technique so that future conclusions could be applied to the general population.

Conflict of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: López Sanclemente MC, Robres J, López Cano M, Barri J, Lozoya R, López S, et al. Neumoperitoneo preoperatorio progresivo en pacientes con hernias gigantes de la pared abdominal. Cir Esp. 2013;91:444–449.

Part of this study was presented at the 32nd International Congress of the European Hernia Society, in Istanbul, Turkey on October 8, 2010.