Although it is not uncommon to diagnose Nocardia infections, the farcinica species, onset of clinical presentation, peculiar progression in the organism and consequent treatment make the case presented herein particularly unusual.

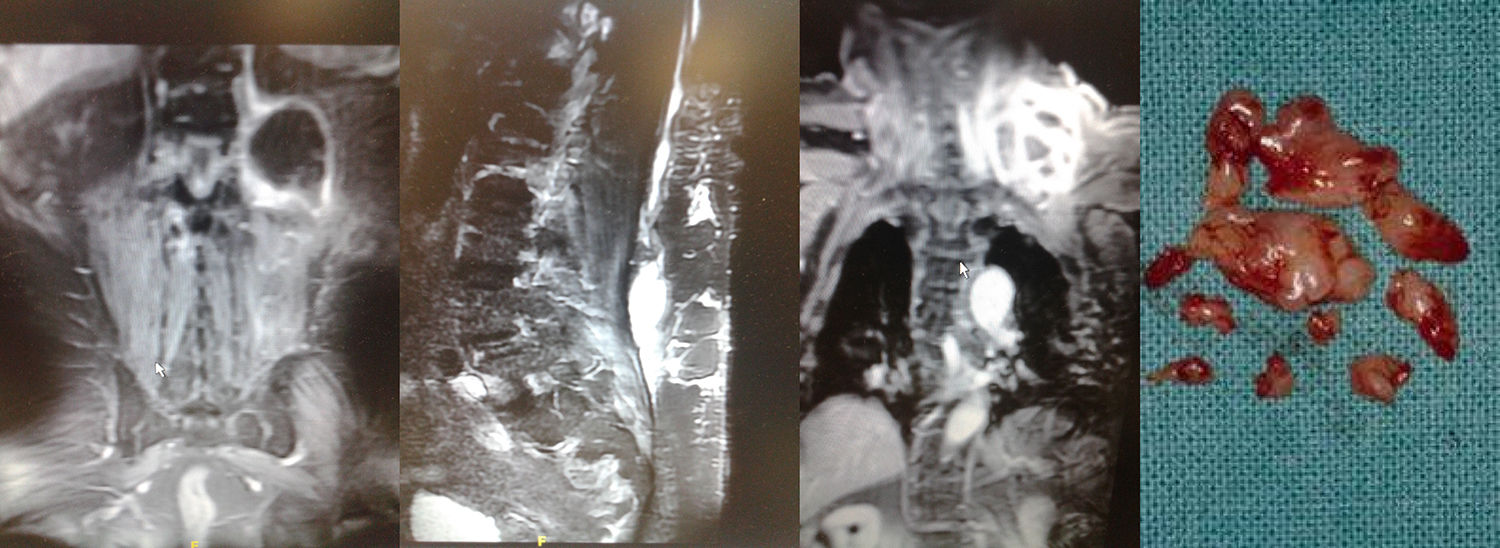

The patient is a 78-year-old obese male with renal insufficiency, hypertension and decompensated diabetes. He was admitted with general malaise, fever of 40°C and severe pain under the left renal fossa. Work-up detected leukocytosis and neutrophilia, ESR 122mm and negative urine culture. Imaging tests revealed left psoas abscess (Fig. 1), and ultrasound-guided percutaneous drainage was conducted. The cultures of the collected sample identified Nocardia farcinica sensitive to aminoglycosides and linezolid. IV antibiotic therapy was started with the latter at 600mg/12h.

Within 48h, the patient began having ipsilateral dorso-lumbar myalgia that irradiated cranially, making it impossible to sit. An MRI study detected a new abscess in the anterior left paraspinal region under the latissimus dorsi, coinciding with the tip of the catheter. Once withdrawn, the sample culture isolated Nocardia farcinica and Pseudomonas aeruginosa sensitive to quinolones, so ciprofloxacin was administered by IV at 200mg/12h.

Subclinical and apyretic for 4 days, a painless left supraclavicular bulge appeared with edema one week later. Cervical MRI images identified an organized collection under the trapezius progressing toward the scalenes (Fig. 1). During cervicotomy, a small part of the collection was removed, and two 25-mm reactive lymphadenopathies were obtained along with globose fibroconnective fragments; in the exudate, microscopic study identified acid-resistant Gram-positive coccobacillus structures, with no growth in cultures but congruent under microscopy with nocardiosis. Empirical treatment was initiated with co-trimoxazole. Wound revision surgery was conducted several times to clean the surgical bed, which prolonged the hospital stay by 55 days. At the time of discharge, the 3 foci had disappeared, and co-trimoxazole was maintained at 800/160mg/12h/3 months.

The caudocranial progression of abscess collections is explained by the lymphatic circulation. Ascending lymphangitis is associated with a limited group of microorganisms, including nocardiosis, sporotrichosis, atypical mycobacteria and actinomycosis.1

Nocardia is part of normal oral flora. It grows in sandy areas, wetlands and potentially polluted soils, and it can be acquired by direct cutaneous inoculation or inhalation.2,3 Some 85% of case reports show concomitant involvement and/or immunosuppression, including chronic lung disease, diabetes, liver cirrhosis, autoimmune disorders, AIDS, oncological subjects, transplant recipients or those treated with glucocorticoids or immunosuppressants.4

Lymphatic or hematogenous dissemination allows this pathogen to reach any organ, and its main virulence factor is resistance to phagocytosis.1,2 Traumatic implantation in subcutaneous cellular tissue generates a local inflammatory response with distant ulcerative-necrotizing nodules due to its endotoxins.

The most frequent clinical forms are pulmonary (50%), cerebral (35%–40%) and cutaneous (10%–15%) by Nocardia asteroides and brasiliensis.1,3 Only in recent decades have cases of farcinica been reported. The patient described did not have any previous related wounds or infections contiguous to the iliopsoas, although his comorbidity would augment any surface contamination. It seems clear that the paraspinal infection was due to post-evacuation iatrogenesis.

The delayed and focalized appearance in the neck makes it necessary to consider a mechanism of ascending lymphangitis. This represents 25% of nodular lymphangitis, classic of inoculations in the lower extremities but extremely unusual in solitary and distant propagations,2–4 although the lymph node reactivity reinforces this hypothesis. The hematogenous route cannot be justified without fever or systemic disease, which typically affects the CNS, eyes and kidneys.2

The exudate from surgical exposure provides samples for microbiological isolations. Nocardia is suspected in aerobiosis with Gram-positive staining and acid-alcohol resistance to groups of branched bacteria.

This diagnosis is definitive with various cultures (blood agar, Sabouraud dextrose, Löwenstein–Jensen or Thayer–Martin), identifying opaque, dry, faintly orange colonies at 37°C. Casein, xanthine, hypoxanthine and tyrosine hydrolysis tests confirm the farcinica species, whose antibiotic resistance is especially significant. Sulfonamides continue to be the treatment of choice for 3 months (6 for mycetomas); effective alternatives include amikacin, imipenem, meropenem and third-generation cephalosporins. Linezolid is a good second-line agent for resistance or allergy.2–4

Please cite this article as: García Callejo J. Absceso de psoas y cuello por Nocardia farcinica. Cir Esp. 2019;97:111–112.