Multiport laparoscopic surgery in colon pathology has been demonstrated as a safe and effective technique. Interest in reducing aggressiveness has led to other procedures being described, such as SILS. The aim of this meta-analysis is to evaluate feasibility and security of SILS technique in colonic surgery.

Material and methodsA meta-analysis of 27 observational studies and one prospective randomised trial has been conducted by the use of random-effects models.

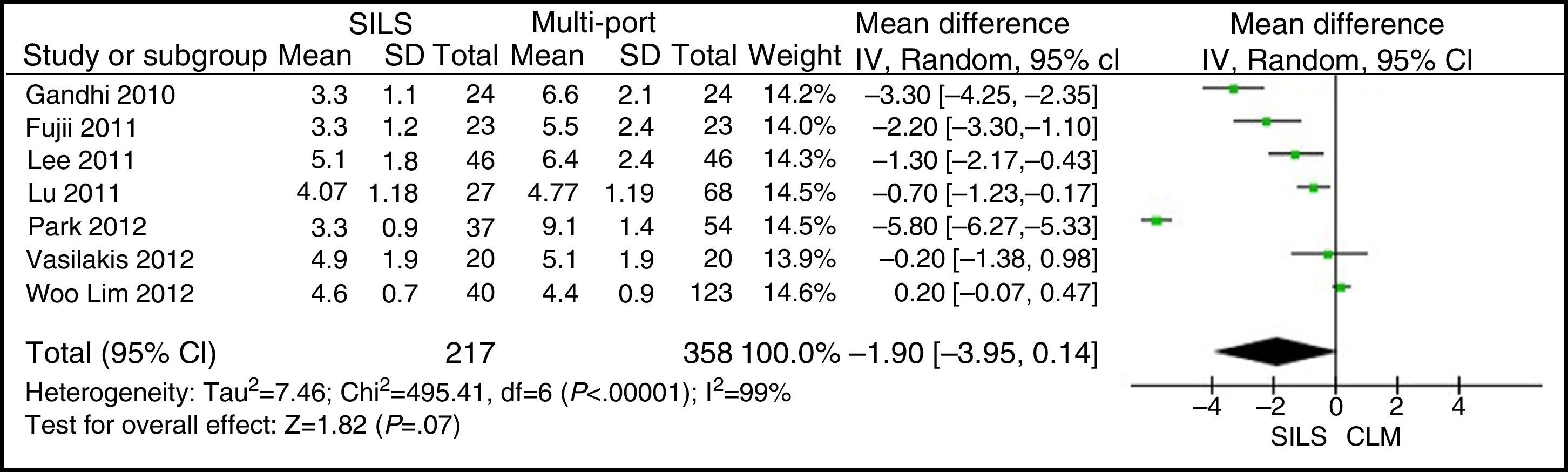

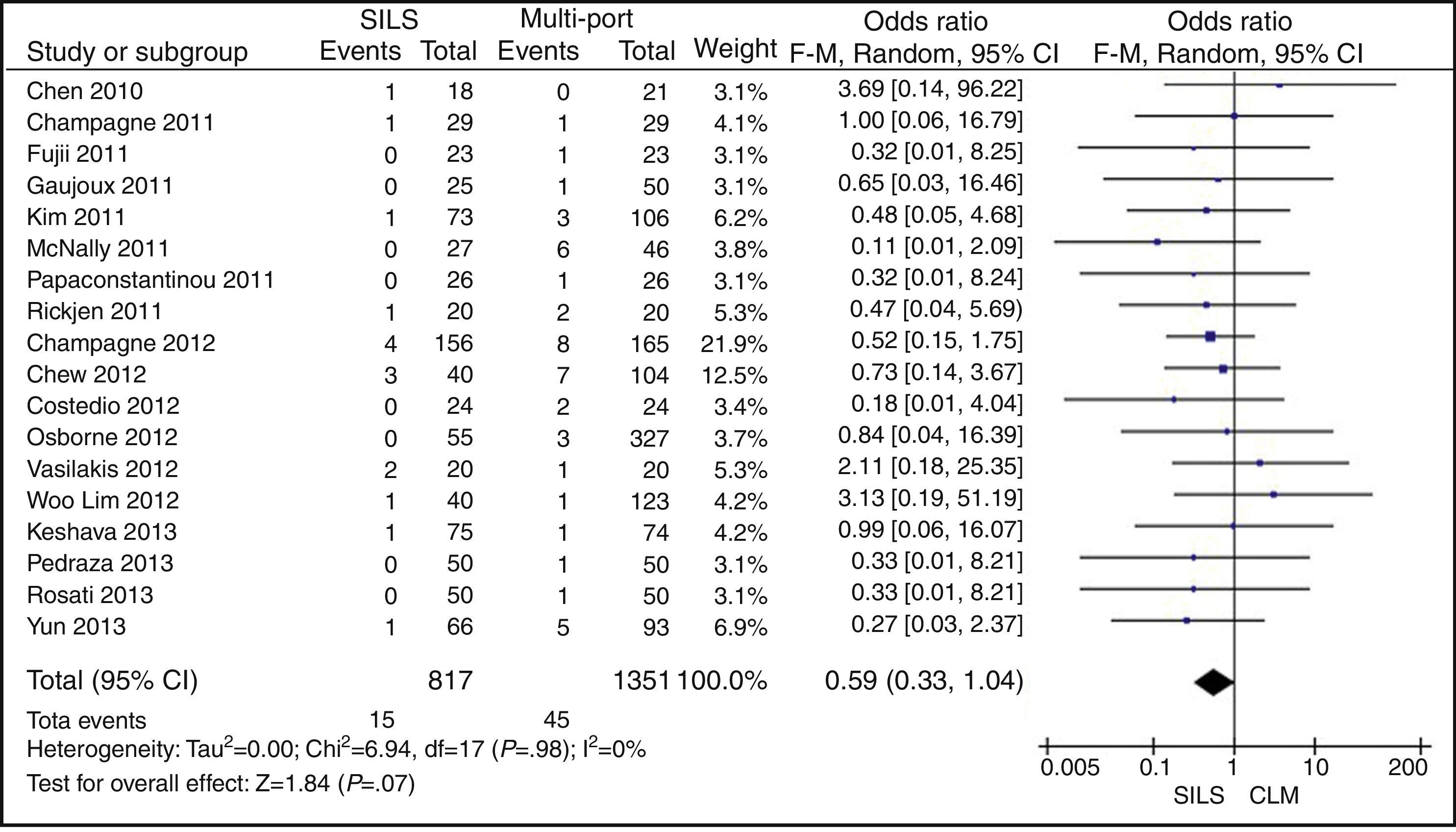

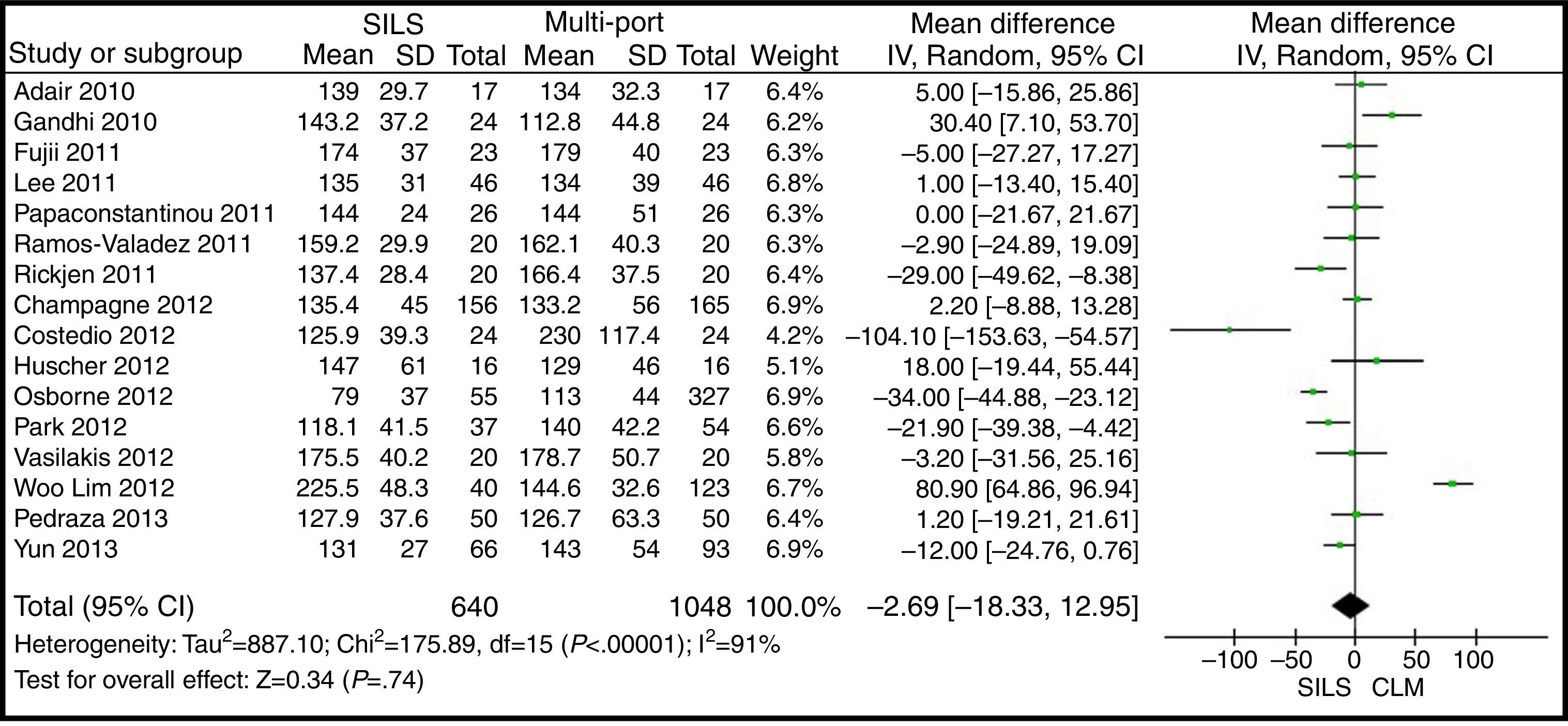

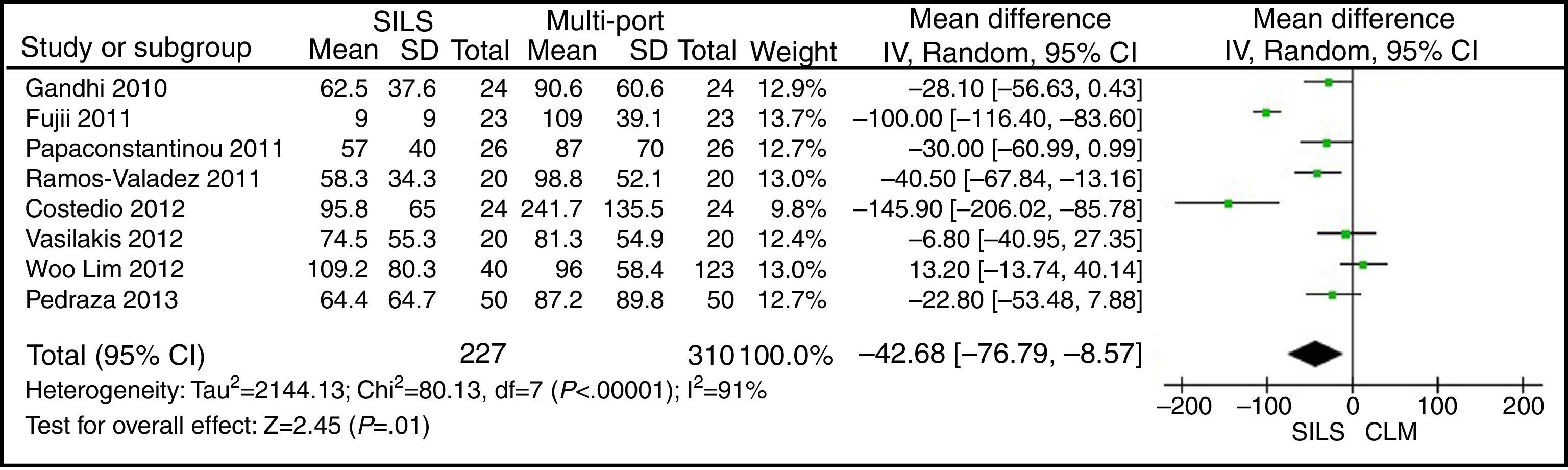

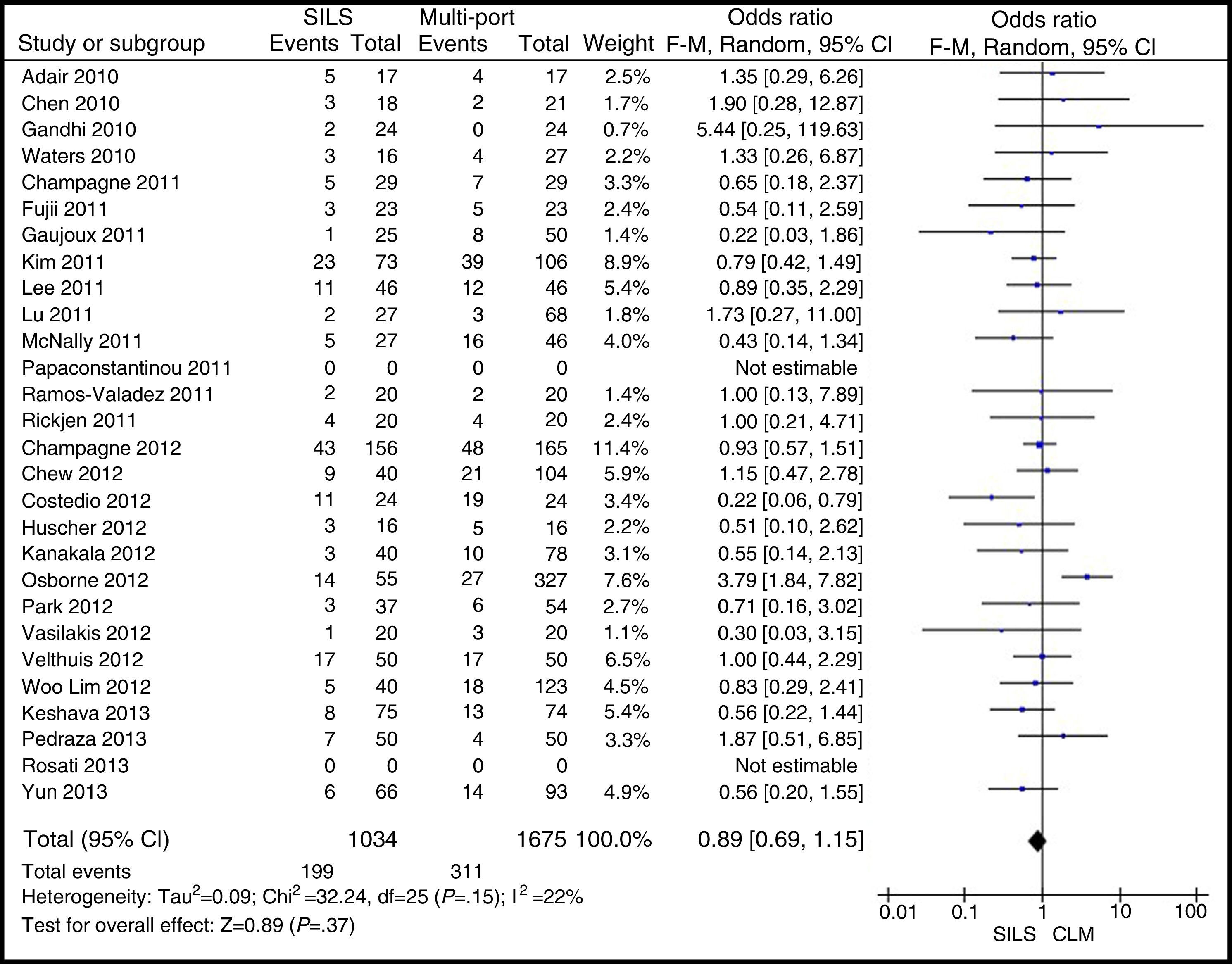

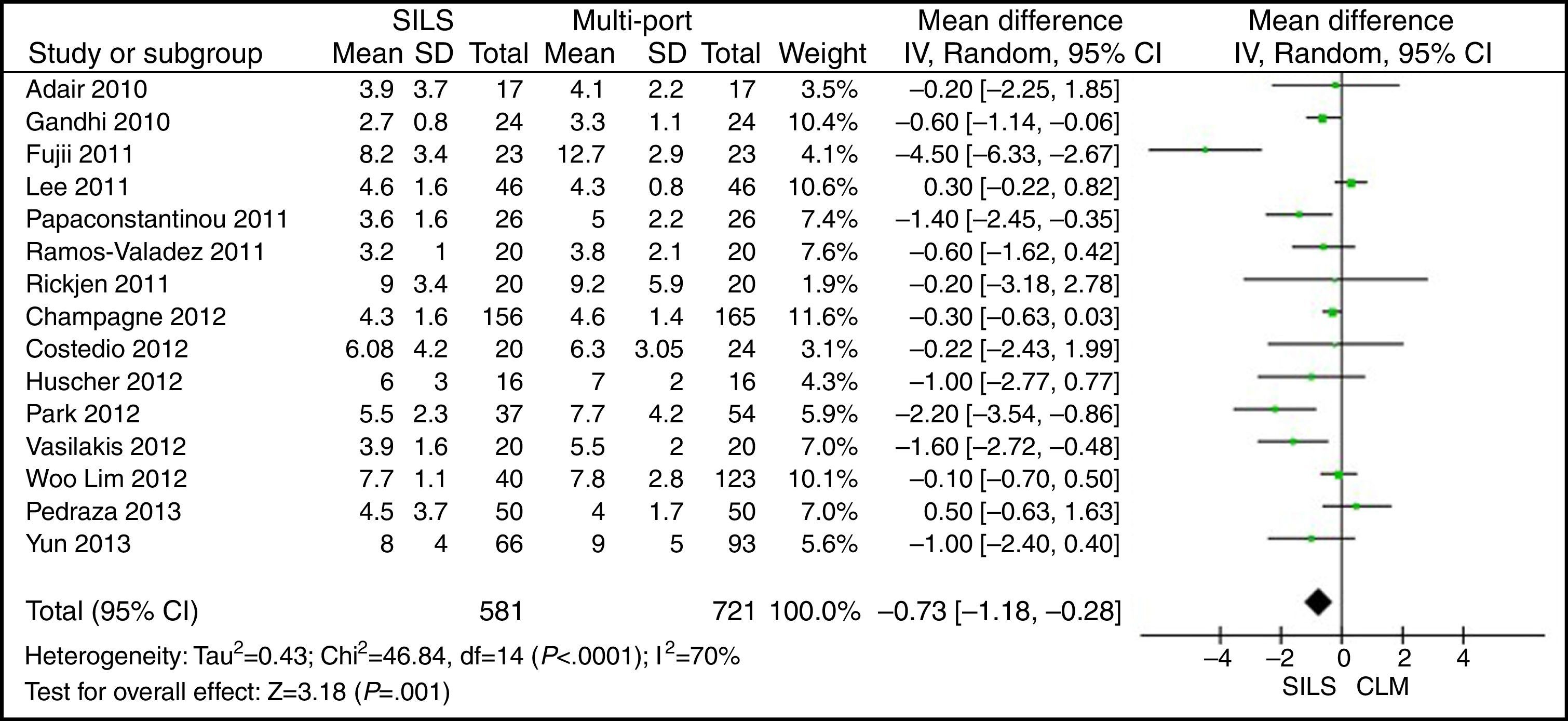

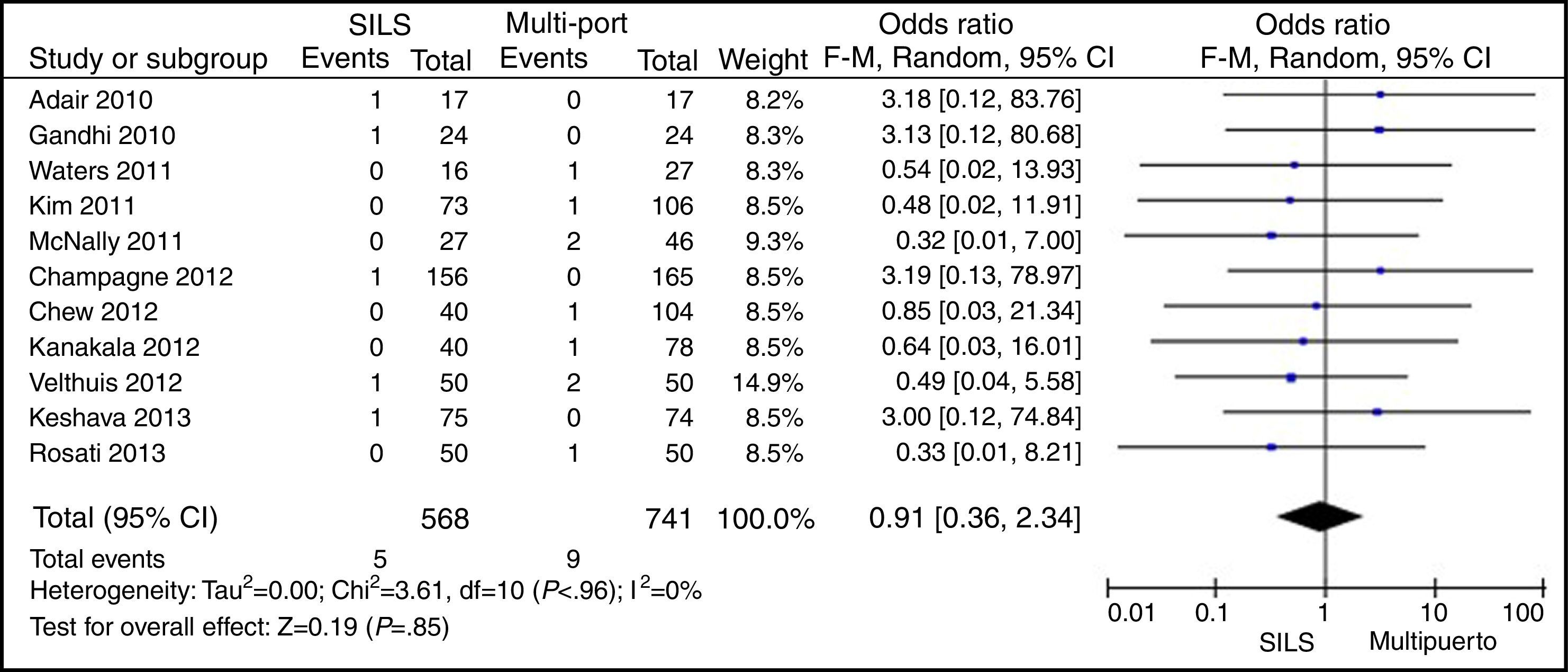

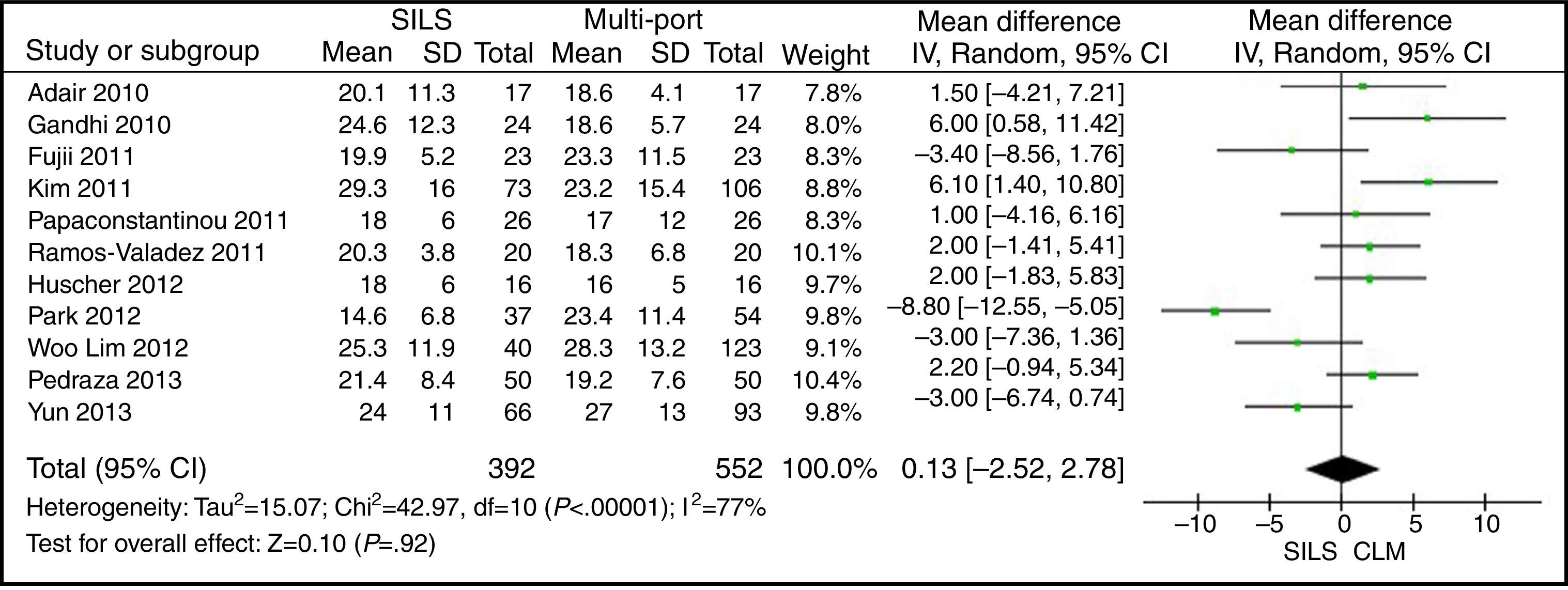

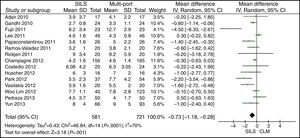

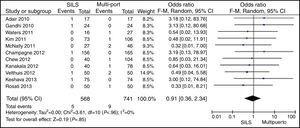

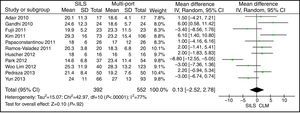

ResultsA total amount of 2870 procedures was analysed: 1119 SILS and 1751 MLC. We did not find statistically significant differences between SILS and MLC in age (WMD 0.28 [−1.13, 1.68]; P=.70), BMI (WMD −0.63 [−1.34, 0.08]; P=.08), ASA score (WMD −0.02 [−0.08, 0.04]; P=.51), length of incision (WMD −1.90 [−3.95, 0.14]; P=.07), operating time (WMD −2.69 (−18.33, 12.95]; P=.74), complications (OR=0.89 [0.69, 1.15]; P=.37), conversion to laparotomy (OR=0.59 [0.33, 1.04]; P=.07), mortality (OR=0.91 [0.36, 2.34]; P=.85) or number of lymph nodes harvested (WMD 0.13 [−2.52, 2.78]; P=.92). The blood loss was significantly lower in the SILS group (WMD −42.68 [−76.79, −8.57]; P=.01) and the length of hospital stay was also significantly lower in the SILS group (WMD −0.73 [−1.18, −0.28]; P=.001).

ConclusionSingle-port laparoscopic colectomy is a safe and effective technique with additional subtle benefits compared to multiport laparoscopic colectomy. However, further prospective randomised studies are needed before single-port colectomy can be considered an alternative to multiport laparoscopic surgery of the colon.

La cirugía laparoscópica multipuerto (CLM) ha demostrado su seguridad y efectividad en la cirugía del colon. Con la intención de reducir la agresividad surgen otras técnicas como la cirugía por puerto único (SILS). El objetivo de este metaanálisis es evaluar la seguridad y la viabilidad de la técnica SILS en la cirugía del colon.

Material y métodosSe realiza un metaanálisis de 27 estudios observacionales y uno prospectivo aleatorizado mediante el modelo de efectos aleatorios.

ResultadosSe han analizado 2.870 procedimientos: 1.119 SILS y 1.751 CLM. No se han encontrado diferencias estadísticamente significativas en la edad (DMP 0,28 [−1,13, 1,68]; p=0,70), IMC (DMP −0,63 [−1,34, 0,08]), ASA (DMP −0,02 [−0,08, 0,04]; p=0,51), longitud de incisión (DMP −1,90 [−3,95, 0,14]; p=0,07), tiempo operatorio (DMP −2,69 [−18,33, 12,95]; p=0,74), complicaciones (OR=0,89 [0,69, 1,15]]; p=0,37), conversión a laparotomía (OR=0,59 [0,33, 1,04]; p=0,07), mortalidad (OR=0,91 [0,36, 2,34]; p=0,85) o número de ganglios obtenidos (DMP 0,13 [−2,52, 2,78]; p=0,92). La pérdida de sangre (DMP −42,68 [−76,79, −8,57]; p=0,01) y la estancia hospitalaria (DMP −0,73 [−1,18, −0,28]; p=0,001) son significativamente menores en el grupo SILS.

ConclusionesLa cirugía colorrectal mediante SILS es segura y efectiva, con ligeros beneficios respecto a la CLM. Sin embargo, se necesitan más estudios aleatorizados antes de que la SILS se pueda considerar una alternativa a la CLM.

Multiport laparoscopic colectomy (MLC) is a safe and effective technique, a fact that has been confirmed by many prospective randomised studies that have shown a lower level of blood loss, a better postoperative recovery, a shorter length of hospital stay, and similar oncological results when compared to open colectomy.1–4 With the aim of reducing aggressiveness and improving MLC results, other procedures have been described, such as mini-laparoscopic surgery, natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES)5 and single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS). Due to its similarity to MLC, only SILS has been adopted by a wide group of surgeons, mainly in appendectomy and cholecystectomy, as well as in more complex procedures, such as colectomy, showing the safety and effectiveness of the intervention.6,7 In comparison with MLC, SILS could offer potential benefits like better aesthetics, less trauma to the abdominal wall, and a reduction in postoperative pain. However, some disadvantages are that it requires a learning curve, adequate technology, a longer operating time, it is difficult to expose and visualise and it may potentially compromise the oncological results of the malignant disease. This is why some surgeons question whether it is possible for SILS colectomy to offer tangible benefits in comparison with MLC, due to the lack of sufficient scientific evidence to that effect. Although there is an increasing number of studies reporting on SILS colectomy results, few of them compare SILS to MLC, making it necessary to rigorously evaluate the safety, the efficacy, and the oncological results in colorectal cancer before SILS methodology is used in a widespread manner.

The main purpose of this article is to review the published literature on SILS colectomy, using meta-analysis to evaluate comparative studies between MLC and SILS in colorectal disease.

MethodThis meta-analysis was prepared following the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA).8

Search StrategyWe have conducted a systematic search of the major databases, including MEDLINE and PUBMED, articles, clinical trials, reviews and works related to single-port laparoscopic colorectal surgery. The date of the last search was April 30, 2014. Only articles in English and Spanish have been included; papers in other languages have been excluded. The key words searched were: “single incision”, “single port”, “single access”, “colectomy”, “colorectal surgery.” Abstracts have been independently scrutinised by 2 authors (JL and MTS) to determine the eligibility for inclusion in the study. Disagreements were solved by means of a third author. The references mentioned in the selected articles have been analysed to identify possible relevant studies.

Criteria of Selection and Eligibility of the StudiesThe articles were selected if the abstract contained information about patients treated via SILS for colorectal diseases, benign and malignant. Prospective randomised and non-randomised studies have been included, as well as comparative case–control and cohort studies. Articles related to natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES), meta-analyses, reviews, editorials, case series, expert opinions and letters to the director have been excluded, as well as articles referring to series of patients with ≤15 SILS procedures. Multicentric studies containing units and hospitals data, already included in the studies, have also been excluded to avoid duplicating patients.

Data Extraction ProcessThree authors (JL, MTS, and JA) obtained the following data from each study, and then entered them in a database: year of publication, type of study, number of patients treated with each technique, demographic characteristics of the study population (age, gender, ASA score, body mass index [BMI], indication for surgery [benign pathology, malignant pathology, or both], type of surgical procedure, average operating time in minutes [min], blood loss measured in millilitres [ml], conversion to open surgery, length of the incision in centimetres [cm], postoperative complications, average length of hospital stay in days, and mortality. In the studies where oncological procedures have been conducted, the number of lymph nodes harvested was also obtained. The data analysed come exclusively from the published articles. No author was contacted to complete the information.

The parameters analysed in the meta-analysis were: BMI, ASA score, length of the incision, blood loss, operating time, postoperative complications, length of hospital stay, number of lymph nodes, and mortality.

A postoperative complication was defined as a complication that developed within 30 days of the intervention as a direct result of the surgery. The complications were classified by degree of severity, according to the Clavien–Dindo scale.9

The conversion to open surgery was defined as the performance of a laparotomy in both SILS and MLC.

Assessment of the Methodological Quality and of BiasThe quality of the articles included in this meta-analysis was assessed according to the revised and modified Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network,10,11 where the maximum punctuation is 20. A score of <8 equals poor quality; a score between 8 and 14 equals intermediate quality, and a score ≥15 equals very good quality.

Statistical AnalysisAll the data were extracted from the selected articles, tables, and figures, and then entered into an SPSS spreadsheet (SPSS version 19, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The odds ratio (OR) was calculated for binary and qualitative variables according to the random effects method of Mantel–Haenszel. OR is the probability of an event occurring in a group in relation with the probability of that event occurring in another group. This ratio was calculated for the studies that informed the occurrences and non-occurrences of events. The studies where the event did not occur in any of the groups were excluded. An OR<1 was favourable to the SILS group and the OR point estimation of P<.05 was considered to be statistically significant if 95% of the confidence interval (CI) did not include the value 1. The weighted mean difference (WMD) was used for the quantitative variables in the studies that included the mean and the standard deviation. Those studies that did not contain that information were excluded. A WMD<0 was favourable to the SILS group and was considered statistically significant with P<.05, if 95% of the CI did not include the value 0.

The degree of heterogeneity among studies was also analysed (the variation in the results among them), by means of τ2, χ2 (Cochrane Q) and I2, where τ2 values >1.00, χ2 values associated to P<.01 and I2 values >50 were indicators of heterogeneity.

Statistical analysis was performed with the statistical software Review Manager (REVMAN), version 5.0 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2008).

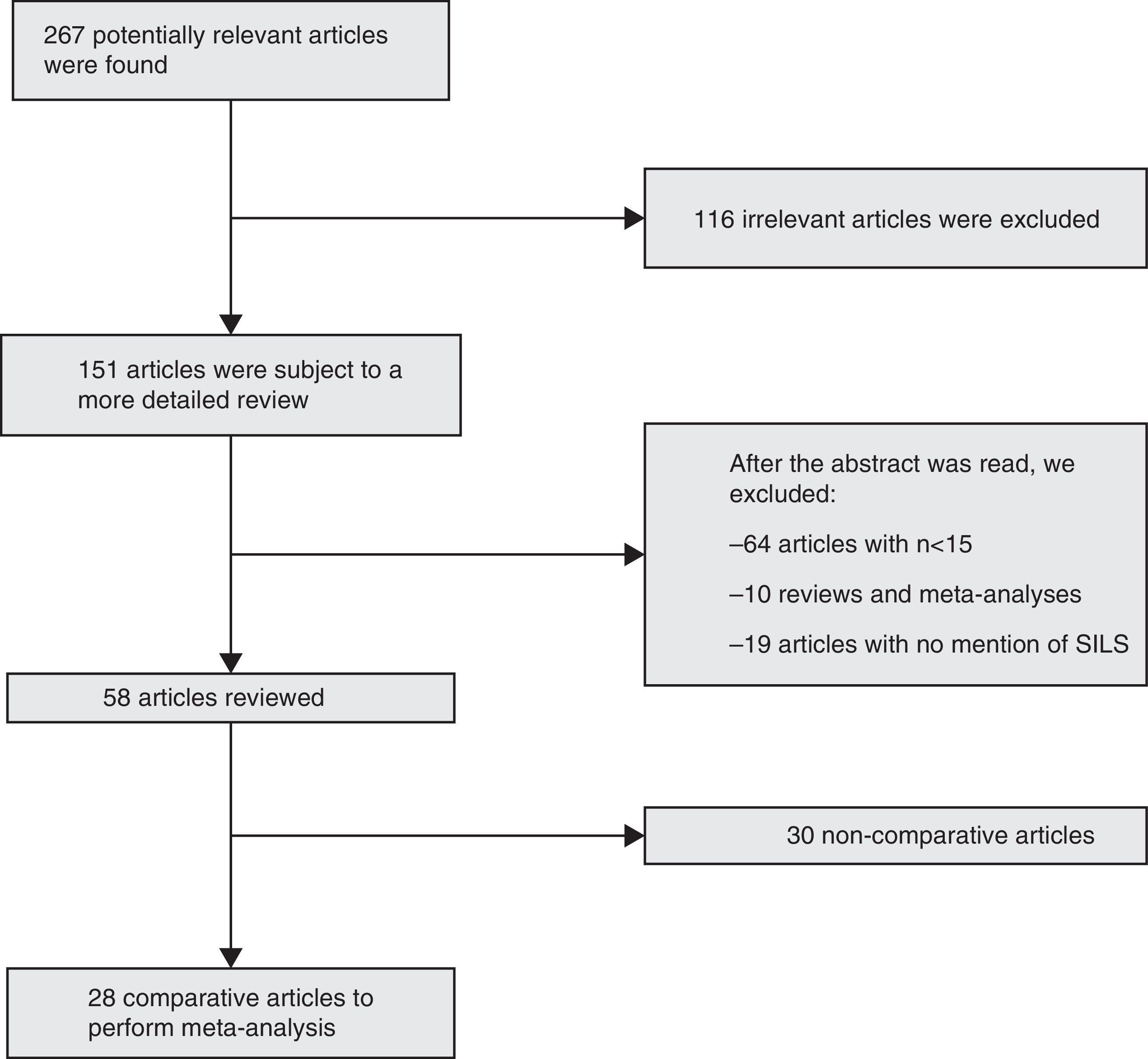

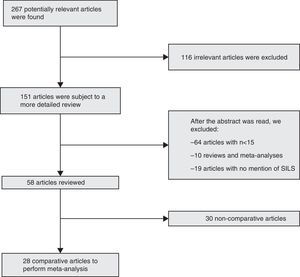

ResultsBibliographic SearchFrom January, 2008 to April, 2014, we collected 267 articles using the inclusion criteria for the search. After the exclusion criteria was used, we obtained 28 comparative articles to be included in the meta-analysis12–39: 27 comparative studies, and one prospective randomised study29 (Fig. 1).

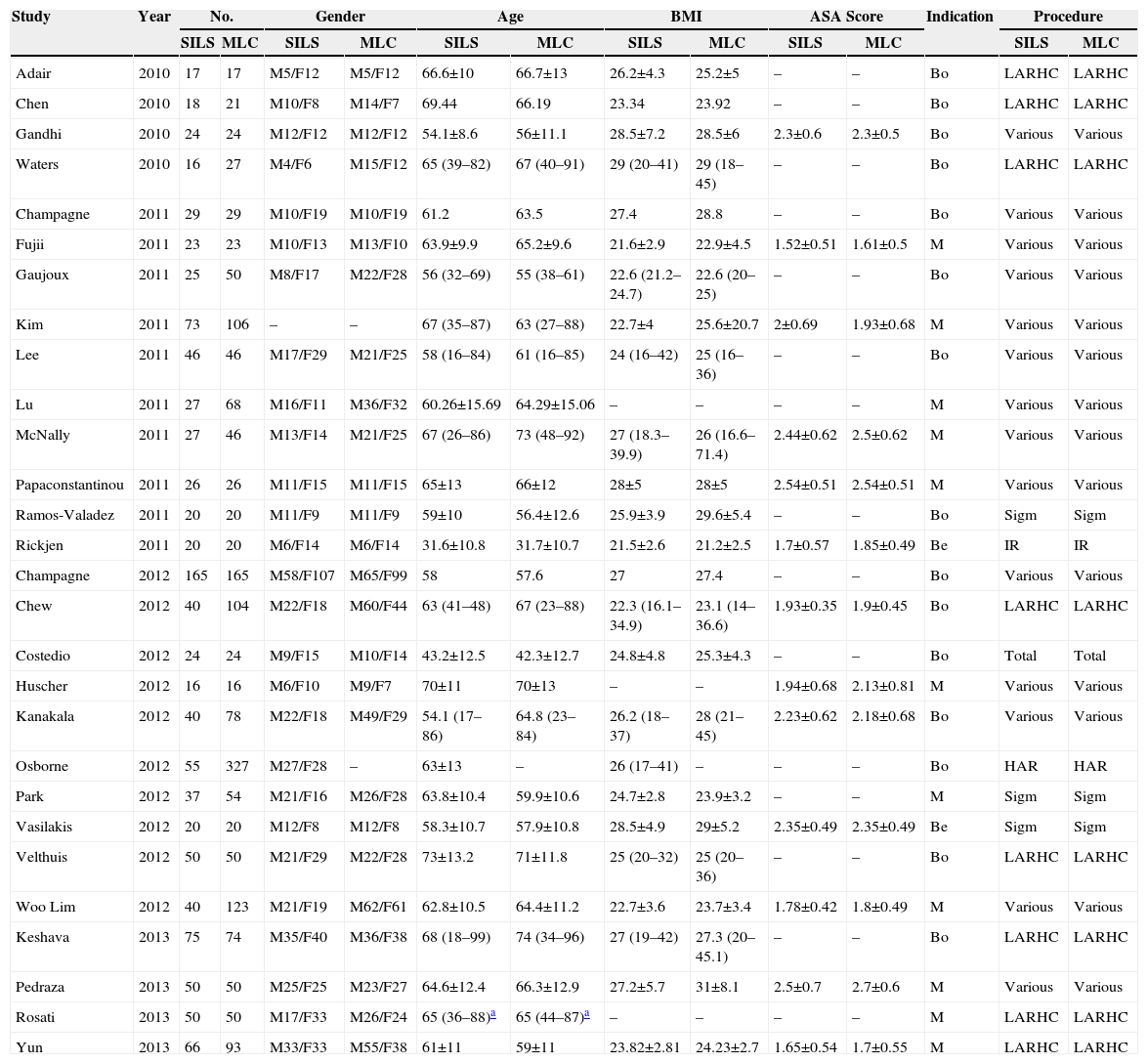

Characteristics of the StudiesAccording to the modified Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network classification,10,11 the average quality of the methodology used in the articles included in the meta-analysis was 13.21±1.87 with a range of (9–16). This means they are intermediate to good quality studies. The 28 studies of this meta-analysis included 2870 patients: 1119 treated via SILS and 1751 via MLC. Out of 28 studies, 11 compared malignant disease17,19,21–23,29,32,35,37–39; 2 compared benign diseases,25,33 and 15 compared benign and malignant diseases.12–16,18,20,24,26–28,30,31,34,36 The type of colectomy more frequently performed was the right hemicolectomy. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of all the procedures included. Table 2 shows the data collected individually from each study included in the meta-analysis.

Demographic Characteristics of Studies Included.

| Study | Year | No. | Gender | Age | BMI | ASA Score | Indication | Procedure | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SILS | MLC | SILS | MLC | SILS | MLC | SILS | MLC | SILS | MLC | SILS | MLC | |||

| Adair | 2010 | 17 | 17 | M5/F12 | M5/F12 | 66.6±10 | 66.7±13 | 26.2±4.3 | 25.2±5 | – | – | Bo | LARHC | LARHC |

| Chen | 2010 | 18 | 21 | M10/F8 | M14/F7 | 69.44 | 66.19 | 23.34 | 23.92 | – | – | Bo | LARHC | LARHC |

| Gandhi | 2010 | 24 | 24 | M12/F12 | M12/F12 | 54.1±8.6 | 56±11.1 | 28.5±7.2 | 28.5±6 | 2.3±0.6 | 2.3±0.5 | Bo | Various | Various |

| Waters | 2010 | 16 | 27 | M4/F6 | M15/F12 | 65 (39–82) | 67 (40–91) | 29 (20–41) | 29 (18–45) | – | – | Bo | LARHC | LARHC |

| Champagne | 2011 | 29 | 29 | M10/F19 | M10/F19 | 61.2 | 63.5 | 27.4 | 28.8 | – | – | Bo | Various | Various |

| Fujii | 2011 | 23 | 23 | M10/F13 | M13/F10 | 63.9±9.9 | 65.2±9.6 | 21.6±2.9 | 22.9±4.5 | 1.52±0.51 | 1.61±0.5 | M | Various | Various |

| Gaujoux | 2011 | 25 | 50 | M8/F17 | M22/F28 | 56 (32–69) | 55 (38–61) | 22.6 (21.2–24.7) | 22.6 (20–25) | – | – | Bo | Various | Various |

| Kim | 2011 | 73 | 106 | – | – | 67 (35–87) | 63 (27–88) | 22.7±4 | 25.6±20.7 | 2±0.69 | 1.93±0.68 | M | Various | Various |

| Lee | 2011 | 46 | 46 | M17/F29 | M21/F25 | 58 (16–84) | 61 (16–85) | 24 (16–42) | 25 (16–36) | – | – | Bo | Various | Various |

| Lu | 2011 | 27 | 68 | M16/F11 | M36/F32 | 60.26±15.69 | 64.29±15.06 | – | – | – | – | M | Various | Various |

| McNally | 2011 | 27 | 46 | M13/F14 | M21/F25 | 67 (26–86) | 73 (48–92) | 27 (18.3–39.9) | 26 (16.6–71.4) | 2.44±0.62 | 2.5±0.62 | M | Various | Various |

| Papaconstantinou | 2011 | 26 | 26 | M11/F15 | M11/F15 | 65±13 | 66±12 | 28±5 | 28±5 | 2.54±0.51 | 2.54±0.51 | M | Various | Various |

| Ramos-Valadez | 2011 | 20 | 20 | M11/F9 | M11/F9 | 59±10 | 56.4±12.6 | 25.9±3.9 | 29.6±5.4 | – | – | Bo | Sigm | Sigm |

| Rickjen | 2011 | 20 | 20 | M6/F14 | M6/F14 | 31.6±10.8 | 31.7±10.7 | 21.5±2.6 | 21.2±2.5 | 1.7±0.57 | 1.85±0.49 | Be | IR | IR |

| Champagne | 2012 | 165 | 165 | M58/F107 | M65/F99 | 58 | 57.6 | 27 | 27.4 | – | – | Bo | Various | Various |

| Chew | 2012 | 40 | 104 | M22/F18 | M60/F44 | 63 (41–48) | 67 (23–88) | 22.3 (16.1–34.9) | 23.1 (14–36.6) | 1.93±0.35 | 1.9±0.45 | Bo | LARHC | LARHC |

| Costedio | 2012 | 24 | 24 | M9/F15 | M10/F14 | 43.2±12.5 | 42.3±12.7 | 24.8±4.8 | 25.3±4.3 | – | – | Bo | Total | Total |

| Huscher | 2012 | 16 | 16 | M6/F10 | M9/F7 | 70±11 | 70±13 | – | – | 1.94±0.68 | 2.13±0.81 | M | Various | Various |

| Kanakala | 2012 | 40 | 78 | M22/F18 | M49/F29 | 54.1 (17–86) | 64.8 (23–84) | 26.2 (18–37) | 28 (21–45) | 2.23±0.62 | 2.18±0.68 | Bo | Various | Various |

| Osborne | 2012 | 55 | 327 | M27/F28 | – | 63±13 | – | 26 (17–41) | – | – | – | Bo | HAR | HAR |

| Park | 2012 | 37 | 54 | M21/F16 | M26/F28 | 63.8±10.4 | 59.9±10.6 | 24.7±2.8 | 23.9±3.2 | – | – | M | Sigm | Sigm |

| Vasilakis | 2012 | 20 | 20 | M12/F8 | M12/F8 | 58.3±10.7 | 57.9±10.8 | 28.5±4.9 | 29±5.2 | 2.35±0.49 | 2.35±0.49 | Be | Sigm | Sigm |

| Velthuis | 2012 | 50 | 50 | M21/F29 | M22/F28 | 73±13.2 | 71±11.8 | 25 (20–32) | 25 (20–36) | – | – | Bo | LARHC | LARHC |

| Woo Lim | 2012 | 40 | 123 | M21/F19 | M62/F61 | 62.8±10.5 | 64.4±11.2 | 22.7±3.6 | 23.7±3.4 | 1.78±0.42 | 1.8±0.49 | M | Various | Various |

| Keshava | 2013 | 75 | 74 | M35/F40 | M36/F38 | 68 (18–99) | 74 (34–96) | 27 (19–42) | 27.3 (20–45.1) | – | – | Bo | LARHC | LARHC |

| Pedraza | 2013 | 50 | 50 | M25/F25 | M23/F27 | 64.6±12.4 | 66.3±12.9 | 27.2±5.7 | 31±8.1 | 2.5±0.7 | 2.7±0.6 | M | Various | Various |

| Rosati | 2013 | 50 | 50 | M17/F33 | M26/F24 | 65 (36–88)a | 65 (44–87)a | – | – | – | – | M | LARHC | LARHC |

| Yun | 2013 | 66 | 93 | M33/F33 | M55/F38 | 61±11 | 59±11 | 23.82±2.81 | 24.23±2.7 | 1.65±0.54 | 1.7±0.55 | M | LARHC | LARHC |

Bo: both; Be: benign; LARHC: laparoscopically assisted right hemicolectomy; HAR: anterior resection; M: malignant; IR: ileocolic resection; Sigm: sigmoidectomy.

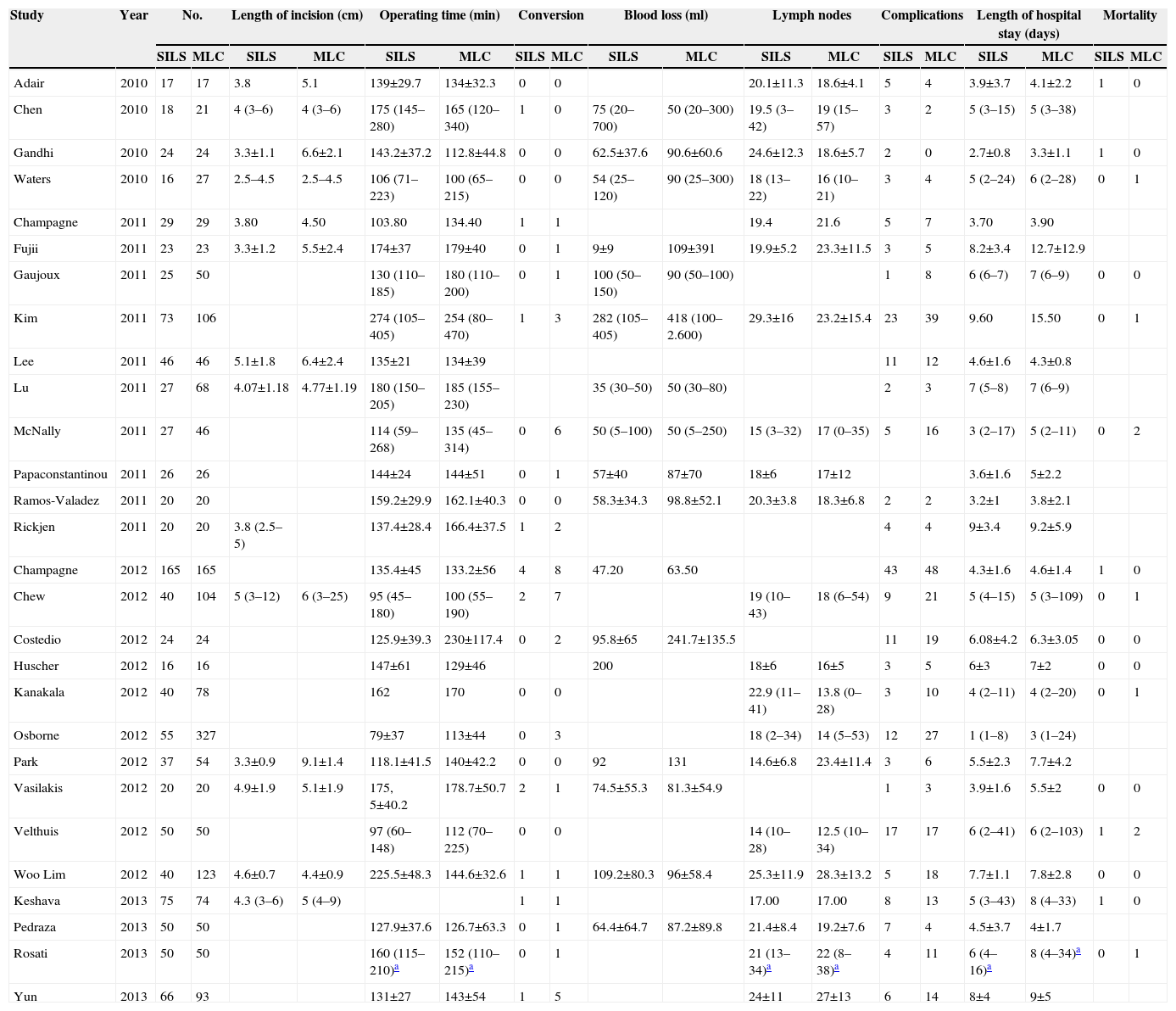

Variables Collected From the Studies Included.

| Study | Year | No. | Length of incision (cm) | Operating time (min) | Conversion | Blood loss (ml) | Lymph nodes | Complications | Length of hospital stay (days) | Mortality | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SILS | MLC | SILS | MLC | SILS | MLC | SILS | MLC | SILS | MLC | SILS | MLC | SILS | MLC | SILS | MLC | SILS | MLC | ||

| Adair | 2010 | 17 | 17 | 3.8 | 5.1 | 139±29.7 | 134±32.3 | 0 | 0 | 20.1±11.3 | 18.6±4.1 | 5 | 4 | 3.9±3.7 | 4.1±2.2 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Chen | 2010 | 18 | 21 | 4 (3–6) | 4 (3–6) | 175 (145–280) | 165 (120–340) | 1 | 0 | 75 (20–700) | 50 (20–300) | 19.5 (3–42) | 19 (15–57) | 3 | 2 | 5 (3–15) | 5 (3–38) | ||

| Gandhi | 2010 | 24 | 24 | 3.3±1.1 | 6.6±2.1 | 143.2±37.2 | 112.8±44.8 | 0 | 0 | 62.5±37.6 | 90.6±60.6 | 24.6±12.3 | 18.6±5.7 | 2 | 0 | 2.7±0.8 | 3.3±1.1 | 1 | 0 |

| Waters | 2010 | 16 | 27 | 2.5–4.5 | 2.5–4.5 | 106 (71–223) | 100 (65–215) | 0 | 0 | 54 (25–120) | 90 (25–300) | 18 (13–22) | 16 (10–21) | 3 | 4 | 5 (2–24) | 6 (2–28) | 0 | 1 |

| Champagne | 2011 | 29 | 29 | 3.80 | 4.50 | 103.80 | 134.40 | 1 | 1 | 19.4 | 21.6 | 5 | 7 | 3.70 | 3.90 | ||||

| Fujii | 2011 | 23 | 23 | 3.3±1.2 | 5.5±2.4 | 174±37 | 179±40 | 0 | 1 | 9±9 | 109±391 | 19.9±5.2 | 23.3±11.5 | 3 | 5 | 8.2±3.4 | 12.7±12.9 | ||

| Gaujoux | 2011 | 25 | 50 | 130 (110–185) | 180 (110–200) | 0 | 1 | 100 (50–150) | 90 (50–100) | 1 | 8 | 6 (6–7) | 7 (6–9) | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Kim | 2011 | 73 | 106 | 274 (105–405) | 254 (80–470) | 1 | 3 | 282 (105–405) | 418 (100–2.600) | 29.3±16 | 23.2±15.4 | 23 | 39 | 9.60 | 15.50 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Lee | 2011 | 46 | 46 | 5.1±1.8 | 6.4±2.4 | 135±21 | 134±39 | 11 | 12 | 4.6±1.6 | 4.3±0.8 | ||||||||

| Lu | 2011 | 27 | 68 | 4.07±1.18 | 4.77±1.19 | 180 (150–205) | 185 (155–230) | 35 (30–50) | 50 (30–80) | 2 | 3 | 7 (5–8) | 7 (6–9) | ||||||

| McNally | 2011 | 27 | 46 | 114 (59–268) | 135 (45–314) | 0 | 6 | 50 (5–100) | 50 (5–250) | 15 (3–32) | 17 (0–35) | 5 | 16 | 3 (2–17) | 5 (2–11) | 0 | 2 | ||

| Papaconstantinou | 2011 | 26 | 26 | 144±24 | 144±51 | 0 | 1 | 57±40 | 87±70 | 18±6 | 17±12 | 3.6±1.6 | 5±2.2 | ||||||

| Ramos-Valadez | 2011 | 20 | 20 | 159.2±29.9 | 162.1±40.3 | 0 | 0 | 58.3±34.3 | 98.8±52.1 | 20.3±3.8 | 18.3±6.8 | 2 | 2 | 3.2±1 | 3.8±2.1 | ||||

| Rickjen | 2011 | 20 | 20 | 3.8 (2.5–5) | 137.4±28.4 | 166.4±37.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 9±3.4 | 9.2±5.9 | |||||||

| Champagne | 2012 | 165 | 165 | 135.4±45 | 133.2±56 | 4 | 8 | 47.20 | 63.50 | 43 | 48 | 4.3±1.6 | 4.6±1.4 | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Chew | 2012 | 40 | 104 | 5 (3–12) | 6 (3–25) | 95 (45–180) | 100 (55–190) | 2 | 7 | 19 (10–43) | 18 (6–54) | 9 | 21 | 5 (4–15) | 5 (3–109) | 0 | 1 | ||

| Costedio | 2012 | 24 | 24 | 125.9±39.3 | 230±117.4 | 0 | 2 | 95.8±65 | 241.7±135.5 | 11 | 19 | 6.08±4.2 | 6.3±3.05 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Huscher | 2012 | 16 | 16 | 147±61 | 129±46 | 200 | 18±6 | 16±5 | 3 | 5 | 6±3 | 7±2 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Kanakala | 2012 | 40 | 78 | 162 | 170 | 0 | 0 | 22.9 (11–41) | 13.8 (0–28) | 3 | 10 | 4 (2–11) | 4 (2–20) | 0 | 1 | ||||

| Osborne | 2012 | 55 | 327 | 79±37 | 113±44 | 0 | 3 | 18 (2–34) | 14 (5–53) | 12 | 27 | 1 (1–8) | 3 (1–24) | ||||||

| Park | 2012 | 37 | 54 | 3.3±0.9 | 9.1±1.4 | 118.1±41.5 | 140±42.2 | 0 | 0 | 92 | 131 | 14.6±6.8 | 23.4±11.4 | 3 | 6 | 5.5±2.3 | 7.7±4.2 | ||

| Vasilakis | 2012 | 20 | 20 | 4.9±1.9 | 5.1±1.9 | 175, 5±40.2 | 178.7±50.7 | 2 | 1 | 74.5±55.3 | 81.3±54.9 | 1 | 3 | 3.9±1.6 | 5.5±2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Velthuis | 2012 | 50 | 50 | 97 (60–148) | 112 (70–225) | 0 | 0 | 14 (10–28) | 12.5 (10–34) | 17 | 17 | 6 (2–41) | 6 (2–103) | 1 | 2 | ||||

| Woo Lim | 2012 | 40 | 123 | 4.6±0.7 | 4.4±0.9 | 225.5±48.3 | 144.6±32.6 | 1 | 1 | 109.2±80.3 | 96±58.4 | 25.3±11.9 | 28.3±13.2 | 5 | 18 | 7.7±1.1 | 7.8±2.8 | 0 | 0 |

| Keshava | 2013 | 75 | 74 | 4.3 (3–6) | 5 (4–9) | 1 | 1 | 17.00 | 17.00 | 8 | 13 | 5 (3–43) | 8 (4–33) | 1 | 0 | ||||

| Pedraza | 2013 | 50 | 50 | 127.9±37.6 | 126.7±63.3 | 0 | 1 | 64.4±64.7 | 87.2±89.8 | 21.4±8.4 | 19.2±7.6 | 7 | 4 | 4.5±3.7 | 4±1.7 | ||||

| Rosati | 2013 | 50 | 50 | 160 (115–210)a | 152 (110–215)a | 0 | 1 | 21 (13–34)a | 22 (8–38)a | 4 | 11 | 6 (4–16)a | 8 (4–34)a | 0 | 1 | ||||

| Yun | 2013 | 66 | 93 | 131±27 | 143±54 | 1 | 5 | 24±11 | 27±13 | 6 | 14 | 8±4 | 9±5 | ||||||

min: minutes; ml: millilitres.

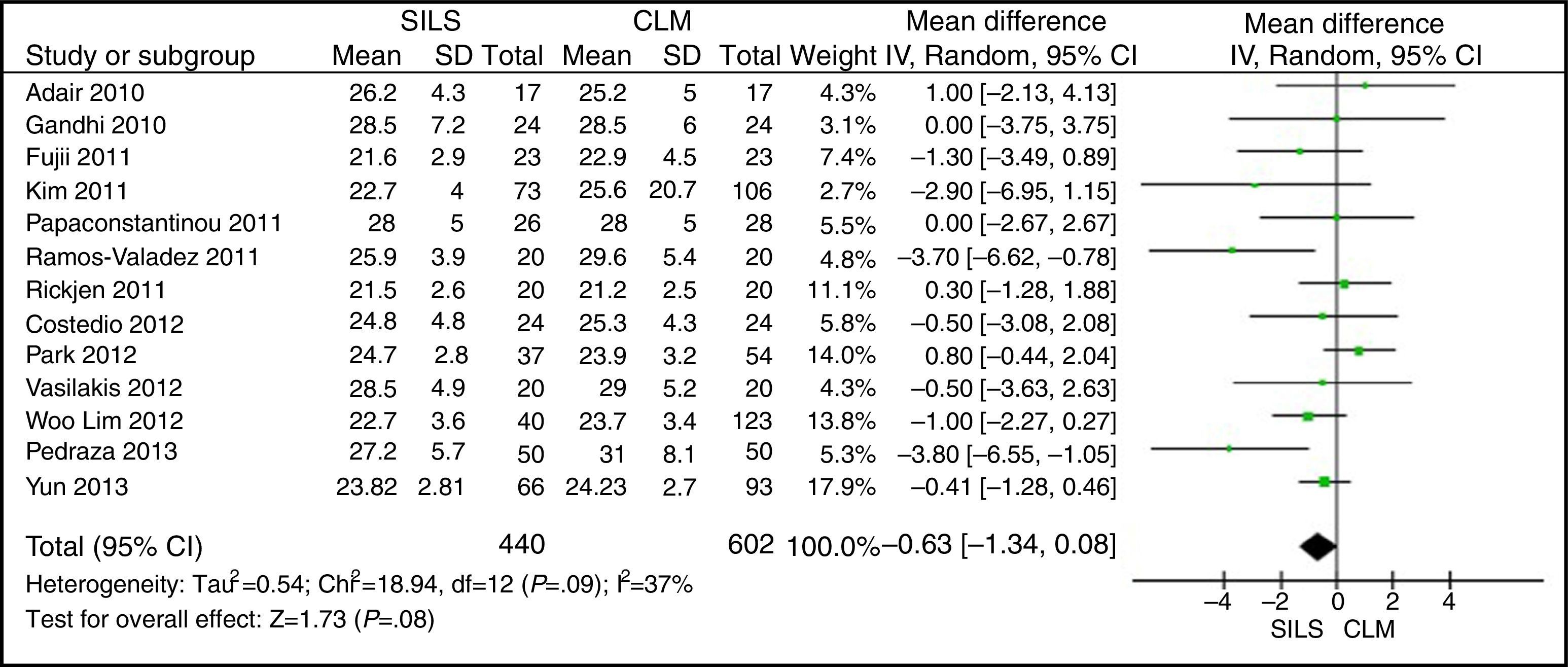

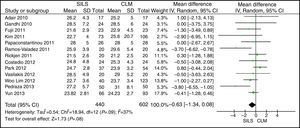

The meta-analysis did not show statistically significant differences between both groups, with a WMD: −0.63 (−1.34, 0.08); P=.08 (Fig. 2).

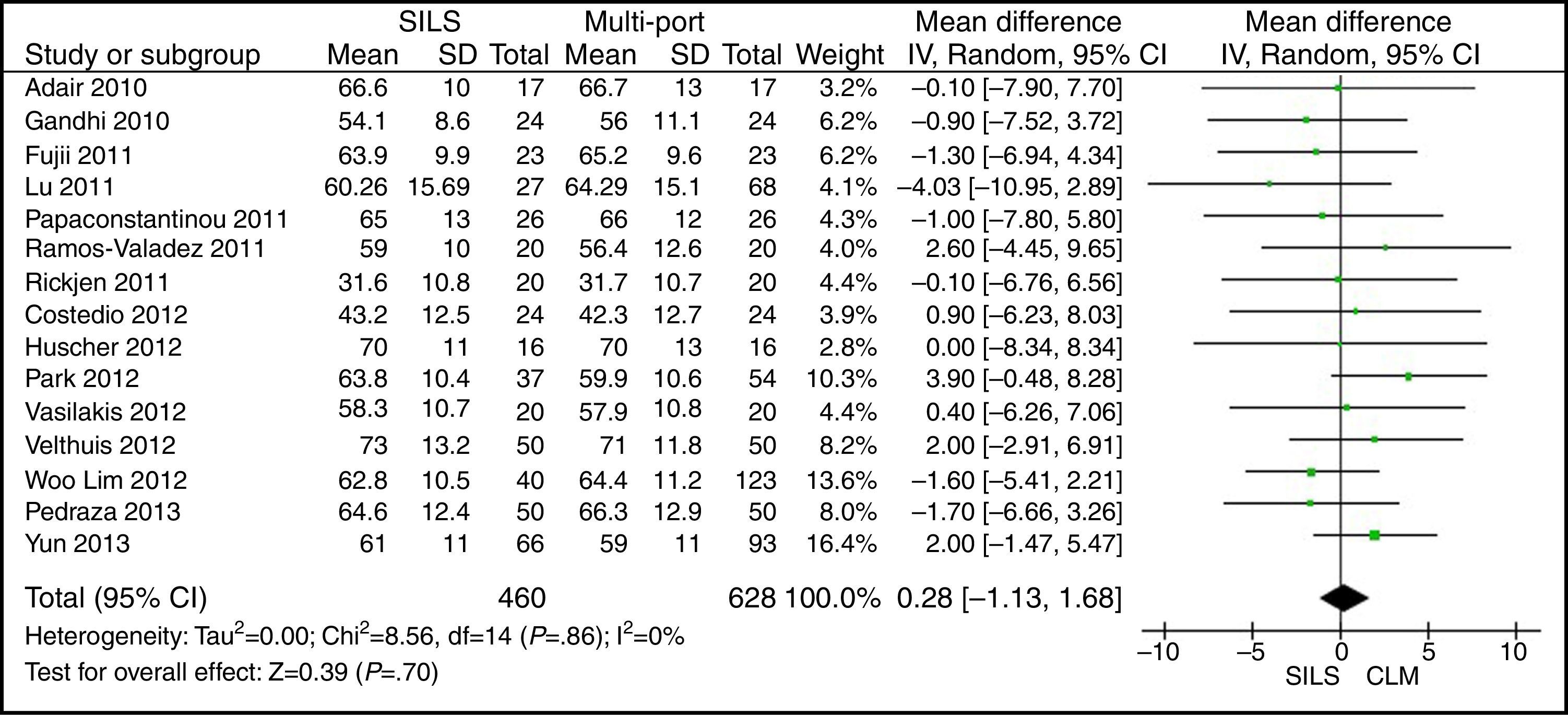

AgeThe meta-analysis estimation did not show statistically significant differences between both groups. WMD: 0.28 (−1.13, 1.68); P=.70 (Fig. 3).

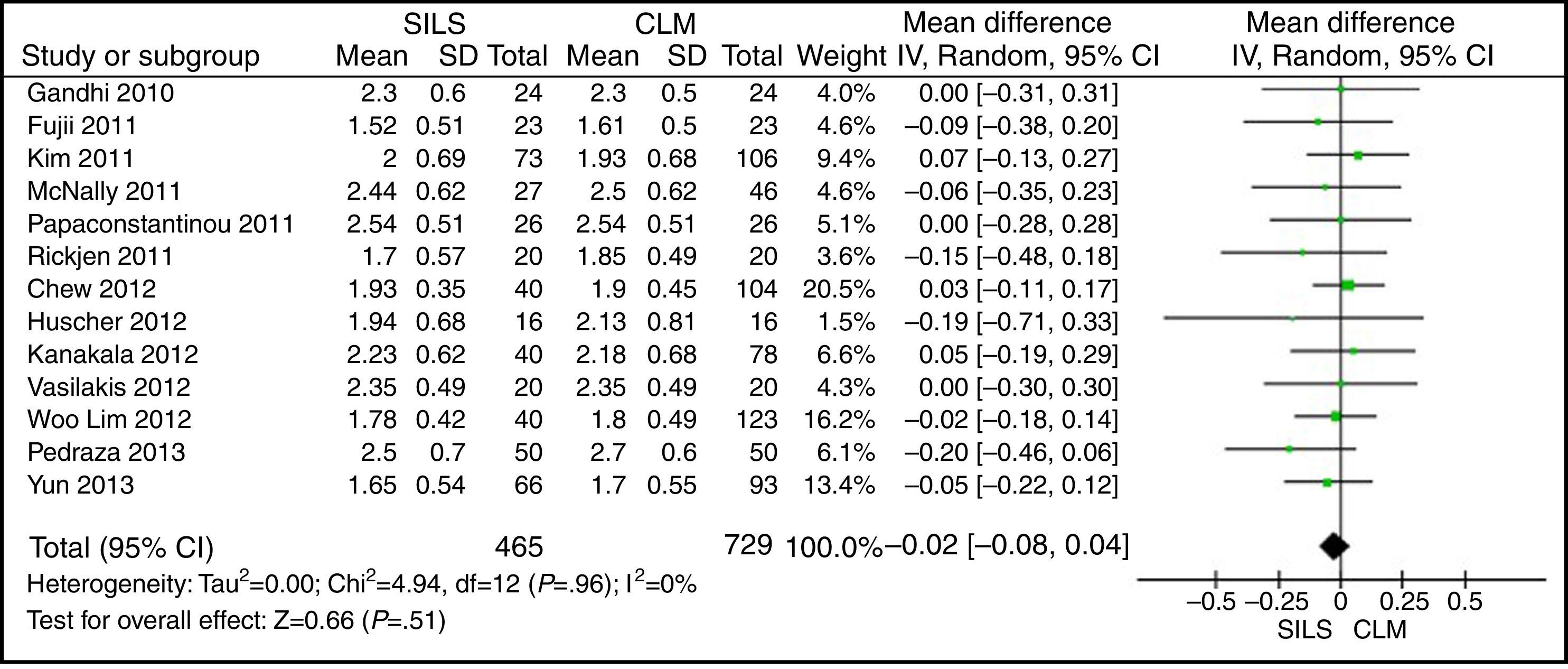

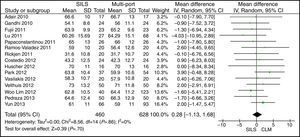

ASA ScoreThe ASA score was informed in 22 studies. Thirteen articles were included in the meta-analysis after the mean and SD were calculated in studies where it was possible to do so.14,17,19,22,23,25,27,29,30,33,35,37,39 The meta-analysis did not show statistically significant differences between both groups. WMD: −0.02 (−0.08, 0.04); P=.51 (Fig. 4).

Length of IncisionThe meta-analysis did not show statistically significant differences for both groups. WMD: −1.90 (−3.95, 0.14); P=.07 (Fig. 5).

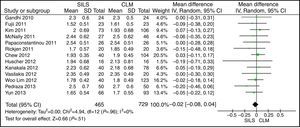

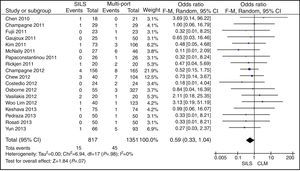

ConversionOut of 1119 SILS procedures, conversion to laparotomy was necessary in 15 (1.34%) patients. Out of 1751 MLC cases, conversion to open surgery was necessary in 45 (2.56%) patients. No statistically significant differences were shown with OR=0.59 (0.33, 1.04); P=.07 (Fig. 6).

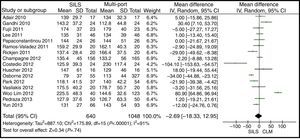

Operating TimeThe meta-analysis estimation did not show statistically significant differences between both groups. WMD: −2.69 (−18.33, 12.95); P=.74 (Fig. 7).

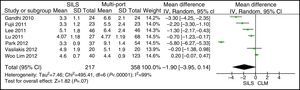

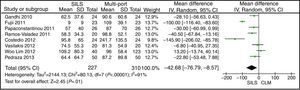

Blood LossThe meta-analysis showed a significantly lower blood loss in the SILS group. WMD: −42.68 (−76.79, −8.57); P=.01 (Fig. 8).

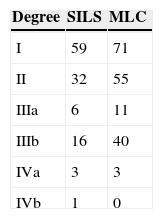

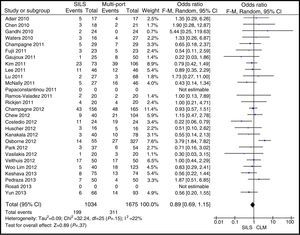

Postoperative ComplicationsPostoperative complications were reported in all studies but one.23 There were 199 (17.78%) postoperative complications in the SILS group and 311 (17.76%) in the MLC group. Table 3 shows complications according to the Clavien–Dindo classification.9 The most frequent complications in both groups were graded type I, excluding studies that did not contribute enough data to grade the complications. There were no differences in the postoperative complications with OR=0.89 (0.69, 1.15); P=.37 (Fig. 9).

Postoperative pain was reported in 6 articles.13,17,19,21,25,33 No statistical study was conducted due to the variability in the type of analgesia and the pain scale grading. Only 2 studies found significant differences: one with less pain in SILS colectomy during the first and second postoperative days, with no repercussions in the length of hospital stay33; and the other, with less pain in MLC colectomy,21 which is attributed to a longer length of umbilical incision in SILS, and to the fact that in the MLC, the specimen is extracted by means of McBurney's incision, which is less painful.

Hospital StayThe meta-analysis showed that the length of hospital stay was also significantly lower in the SILS group. WMD: −0.73 (−1.18, −0.28); P=.001 (Fig. 10).

MortalityOut of 1119 SILS cases, there were 5 (0.44%) deaths. Out of 1751 MLC interventions, 9 (0.51%) patients died. No statistically significant differences were shown with OR=0.91 (0.36, 2.34); P=.85 (Fig. 11).

Isolated Lymph NodesThe meta-analysis did not show statistically significant differences. WMD: 0.13 (−2.52, 2.78); P=.92 (Fig. 12).

DiscussionColon surgery via SILS, as well as in other diseases, is a surgeon's attempt to diminish surgery aggressiveness by reducing the number of ports of entry. The aim is to diminish postoperative pain, reduce complications, improve the time of recovery, and obtain a better aesthetic result, without jeopardising the safety and efficiency of the surgery. The vast majority of these advantages are based on cohort series studies, non-randomised comparative studies, sometimes with contradictory results which may raise more questions than answers. This meta-analysis has intended to answer whether SILS offers benefits as compared to MLC, using the best of the evidence available at present.

Operating time is similar in both groups, although longer in some MLC cases. It is difficult to explain how the operating time could be shorter in SILS colectomy. One possible explanation to this is that MLC procedures, most of the times, are performed by surgeons in training, while SILS are exclusively performed by surgeons with experience in laparoscopic procedures.18,34 Another argument could be the very nature of the patient selection, as with patients with a stoma, which is generally placed at the end of the intervention, since it could be time-saving as the stoma orifice is already made and protected by a wound retractor, so there is no need to close the fascia or the skin in the additional ports, as in the MLC.18 These two arguments, patient selection and the surgeon's expertise, could also be the cause of the increased blood loss in MLC patients.

Among the potential benefits of SILS over MLC is the shorter length of incision, which could contribute to an improvement in the aesthetics of the procedure and a reduction in postoperative pain. In this meta-analysis, the length of the incision was similar in both procedures. This could be so because in the laparoscopic colectomy, the length of the incision is not determined by the access path, whether it is SILS or MLC, but by the specimen size, the obesity and the depth of the abdominal wall, the mobility and thickness of the mesentery and omentum, and the amount of stool in the colon.

On the other hand, the advantage of better aesthetics attributed to SILS could be relevant for patients who underwent SILS cholecystectomy, but it is not clear, and it would probably be an irrelevant advantage for colon cancer patients.

The length of hospital stay was shorter in the SILS colectomy group. Discharge from hospital depends on the recovery programme implemented by each institution, on the operating time, the complexity of the surgery, and the morbidity associated to it. All of these parameters are very difficult to assess in non-prospective randomised studies. In a Cochrane review, comparing “fast track” surgery vs conventional postoperative care in colorectal surgery, the length of hospital stay was found to be shorter in health care centres that provided fast-track recovery programmes.40 Therefore, it is a variable that strongly depends on the centre that performs the study and, although this meta-analysis showed a statistically significant shorter length of hospital stay, results have to be taken with caution.

The majority of studies show that SILS colectomy is a safe technique when compared to MLC. In this meta-analysis, the complications have been similar in both surgical techniques. This shows the technique is safe. In the vast majority of the studies, the selected SILS patients had a low BMI. In addition, the surgeons performing the interventions were skilled in laparoscopic surgery. It is unknown whether the safety and effectiveness will remain the same when operating on patients with more complex health profiles and a higher BMI. Moreover, regarding BMI, the results obtained by meta-analysis show that patients intervened via SILS technique have lower BMIs. It leads to think that there is a selection bias, although the results obtained are not statistically significant. On the other hand, one of the theoretical advantages of the SILS interventions is that there are fewer complications related to trocar ports of entry. MLC requires 4–6 ports. Each port represents a potential risk of bleeding, hernia, or intraperitoneal organ lesions. SILS reduces invasiveness since it only performs a single incision, and this could consequently reduce complication rates. However, there are no conclusive clinical studies that show the actual incidence of these complications, among other things, due to the low incidence of complications related to trocars.

In patients with colon cancer, the number of isolated lymph nodes is relevant for staging, determining a prognosis, and defining therapeutic implications. At present, there are no prospective randomised studies or cohort studies to determine oncological results with SILS, in the long run. In 3 studies (2 retrospective studies,23,39 and one prospective randomised study29), the oncological results in adenocarcinoma of colon are compared in the short run, in both techniques: SILS colectomy and MLC. It is shown that in expert hands it is feasible to achieve a correct oncological resection with SILS, although there is no scientific evidence that proves the benefits via this intervention and no study has been able to show SILS colectomy advantages so far.29 In this meta-analysis, the oncological parameters available in the short run, as the number of isolated lymph nodes, have been the same in both groups: with a mean of 19.22 isolated lymph nodes in SILS colectomy, and 18.55 in MLC. Literature suggests that, for a correct oncological study, there should be a minimum of 12 isolated lymph nodes in colectomies performed for cancer.41 This leads to believe that SILS colectomy is as effective in oncology as MLC, provided the principles of laparoscopic resection of colorectal cancer are maintained: to perform an early ligation of the vascular pedicle, to avoid manipulating the tumour, and to protect the surgical wound for the specimen extraction.

This meta-analysis includes more studies and a larger amount of patients than other meta-analyses conducted before. The results indicated in those meta-analyses are surprising, in some respects: larger number of isolated lymph nodes during oncological resection performed by SILS, giving SILS colectomy a major improvement when compared to MLC.42 The authors are aware that this meta-analysis has some methodological limitations. Thus, in the design of the comparative studies, only one study was prospective randomised29 and the rest were observational studies. This may reduce the quality of the results.

The meta-analyses based on good quality observational studies generally produce estimates similar to those of meta-analyses based on prospective randomised studies,43 which is why observational studies should not be excluded from meta-analyses, as it was demonstrated by the meta-analyses conducted with non-randomised comparative studies of laparoscopic resection of colorectal cancer.44 Other biases in this meta-analysis is that in the majority of SILS colectomy studies, the intervention was conducted by surgeons with experience in laparoscopic surgery, while MLC is performed by surgeons in the process of being trained in laparoscopic colectomy. In addition, SILS studies select patients with lower BMIs, as obese and morbidly obese patients are a difficult population to be treated via SILS due to potential additional traction requirements. For this reason, the results obtained in this meta-analysis should be taken with caution.

In conclusion, based on the results of this meta-analysis, SILS is a safe and effective technique, with additional subtle benefits in comparison with MLC. Development in this area should continue, and prospective randomised studies are needed to be able to consider single-port laparoscopic colectomy an alternative to multi-port laparoscopic colectomy, as the evidence available at present is not enough to determine whether this practice should be a standard in laparoscopic colectomy.

Authors’ ContributionsJ. Luján: study design, data collection, draft of the manuscript; M.T. Soriano: data collection, draft of the manuscript; J. Abrisqueta: data collection, draft of the manuscript, statistical analysis; D. Pérez: data collection, statistical analysis; P. Parrilla: data collection, draft and review of the manuscript.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests.

Please cite this article as: Luján JA, Soriano MT, Abrisqueta J, Pérez D, Parrilla P. Colectomía mediante puerto único vs. colectomía mediante laparoscopia multipuerto. Revisión sistemática y metaanálisis de más de 2.800 procedimientos. Cir Esp. 2015;93:307–319.