Since the first laparoscopic hepatectomy was performed in 19921 and after years of technical and technological improvements, laparoscopic liver surgery is now regarded a feasible and safe technique for selected patients.2,3 Laparoscopy has advantages including less post-operative pain, a shorter hospital stay, an aesthetic benefit and lower blood loss. Furthermore, oncological results have been demonstrated which are comparable to open surgery.4–6

The anatomy of the left lateral sector and the distribution of its portal and suprahepatic pedicles facilitate a laparoscopic approach; many liver surgery groups consider this the technique of choice for a great many lesions located in segments ii and ii–iii.7,8

New laparoscopic techniques have been developed aimed at further minimising aggressive surgery. There is, on the one hand, surgery through natural orifices (NOTES) which presents major technical issues (difficult spatial orientation, contamination of the abdominal cavity and safe closure of the orifice made in access organs) and on the other hand there is surgery through a single incision. This remains a minimally invasive technique and is available to surgeons with experience in laparoscopic surgery as it does not require a multi-disciplinary team and has a relatively short learning curve.9

Single-port laparoscopic surgery has been accepted by digestive surgeons because of its theoretical advantages (less aggressive with earlier recovery and better aesthetic results). There are numerous studies on its application in cholecystectomy, colectomy, bariatric surgery, splenectomy and appendicectomy.10 However, little work on single-port liver resections has been done; the majority is on isolated cases or short series.11,12

Laparoscopic liver resections, for benign and malignant disease, were started in the Hepatobiliary Pancreatic Surgery Unit in February 2002 and single-port cholecystectomy was started in 2009. This background opened the way to considering single-port liver resection.

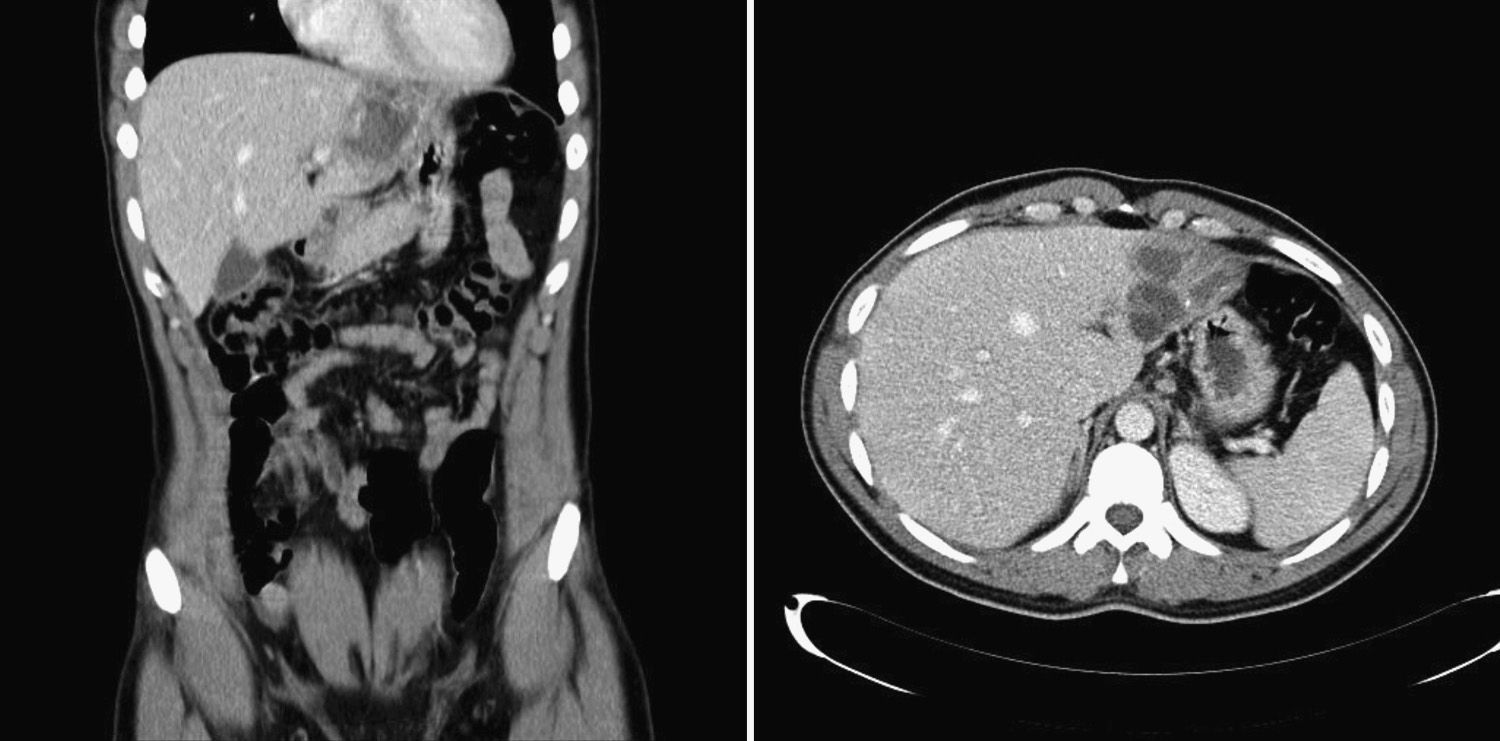

The following is the case of a 27 year-old male patient with no significant medical history, who was admitted via the Accident and Emergency Department with abdominal pain and fever. A slightly elevated serum bilirubin level was detected. Ultrasound, CT and C-MRI showed a 60×53mm cystic lesion in liver segment ii–iii with thickening of the walls and partially calcified trabeculations, indicative of hydatidic cyst (Fig. 1), with no dilatation of the intrahepatic bile duct or communication of the bile duct with the cystic formation. Echinococcus granulosus serology tested positive. After treatment with albendazole for four weeks showing a good clinical outcome, resection of the liver lesion was indicated.

Under general anaesthetic and with the patient in the supine position, legs apart (French position) and in a reverse Trendelenburg position, a transverse incision of approximately 3cm in length was made about 5cm above the umbilicus, slightly lateralised to the right of the patient. The Endocone® (Karl Storz GmbH & Co., Germany) single-port device was placed at this level, it offers six ports of 5mm and two of 10–12mm. A 10mm optic with variable direction of view was used which allowed angles of view from 0° to 120° (Endocameleon®, Karl Storz GmbH & Co., Germany). Intra-operative laparoscopic ultrasound ruled out the presence of other liver lesions and confirmed the irregular cystic lesion of about 6cm in diameter located in segment ii–iii near the exit of the portal branches of both segments.

A bi-segmentectomy ii–iii was performed without hilar clamping, using a harmonic scalpel (Ultracission®, Ethicon Endosurgery Inc., USA) for the parenchymal transection and monopolar coagulation (Tissuelink, EndoFB3.0 Floating Ball, Medtronic Advanced Energy, USA). Three endo-GIA with vascular load were used (ETS 45mm, Ethicon Endosurgery Inc., USA) for the section of the portal branches of segments ii–iii and the left suprahepatic vein. Straight laparoscopic forceps were used to perform traction of the round ligament and to open the transection line, as described in the conventional laparoscopy technique.7

A sheet of sealant, haemostatic material (Tachosil®, Takeda) was placed over the resection bed. The specimen was extracted in a pouch (Endo Catch™ II 15mm Specimen Pouch, Covidien, USA) by expanding the single-port incision at the level of the aponeurosis to 7cm and 5cm at skin level. No drain was left. The incision was closed using a continuous absorbable suture in the peritoneal plane and aponeurosis, and the skin was closed with a 3/0 absorbable subcuticular suture (Fig. 2). The operating time was 120min. The post-operative period was satisfactory and the patient started an oral diet seventeen hours after surgery. Analgesia was administered intravenously for the first 24h and then orally. The patient was discharged on the third post-operative day.

Single-port laparoscopic anatomical liver resection is a feasible, although technically very demanding, approach and can be performed safely in carefully selected cases, with lesions located in the segments where the laparoscopic approach is considered favourable. Greater experience of surgical teams and future technological improvements will determine the role that this single-port approach will play in liver surgery.

Please cite this article as: Cugat Andorra E, Herrero Fonollosa E, Camps Lasa J, García Domingo MI, Carvajal López F. Bisegmentectomía ii–iii hepática laparoscópica por puerto único. Cir Esp. 2013;91:679–681.