Malignization of hidradenitis suppurativa is a rare complication.1 With just over 85 cases published in the English-speaking international literature,2 it is likely an under-diagnosed entity.3 However, in light of the severity and poor prognosis of this well-known complication, it is surprising that there are still patients whose disease progresses to such an extent.

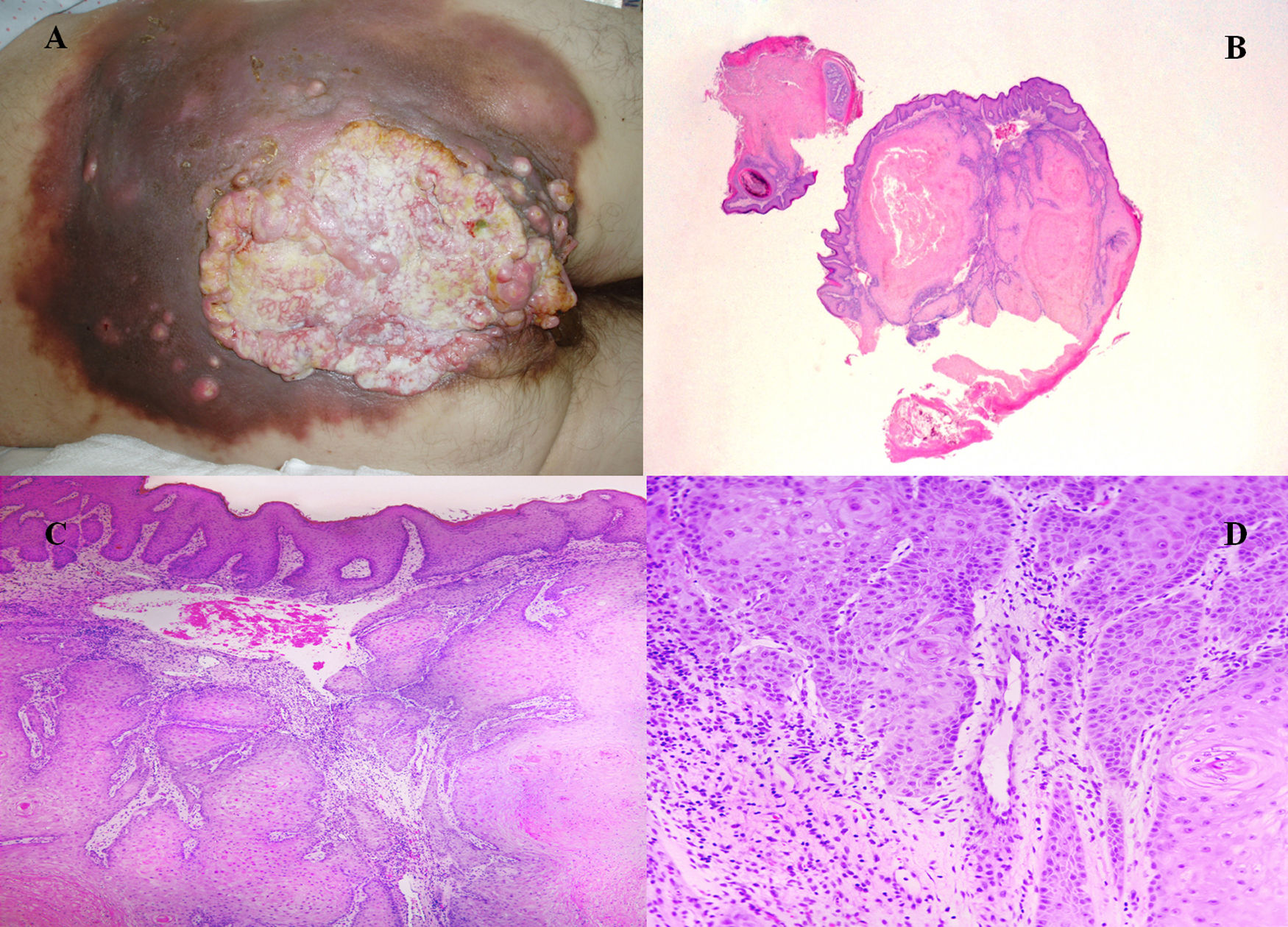

We present a case treated by our service. The patient was a 54-year-old male with a history of perineal and sacral hidradenitis suppurativa that had been treated surgically when he was 14. In adulthood, he developed a bipolar personality disorder that led him to a situation of social isolation; he had been living in poverty for the last several years. The patient came to the emergency department one day due to general malaise and reported losing 15–20kg in the last 6 months, difficulty walking due to the pain, pain in the hypogastrium and rectal tenesmus. He also reported an ulcerated suppurative lesion in the sacral region for the past 3 months. Physical examination revealed a large vegetative sacral lesion extending to both buttocks, with indurated necrotic edges, and multiple suppurative ulcers of a fetid nature (Fig. 1A). Several biopsy samples were taken, and an abdominal-pelvic CT scan was requested due to the suspicion of malignization and to rule out the presence of subcutaneous collections requiring surgical drainage or debridement.

(A) Image of the perineal, bilateral buttock and sacral lesion with suppurative areas and areas of suspected tumor invasion; (B) Well-differentiated endophytic squamous lesion (H&E ×4); (C) Nests of squamous cells with densely eosinophilic cytoplasm (H&E ×40); (D) Epithelial-stromal interface (H&E ×200).

The biopsy study established the diagnosis of well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (Fig. 1B–D).

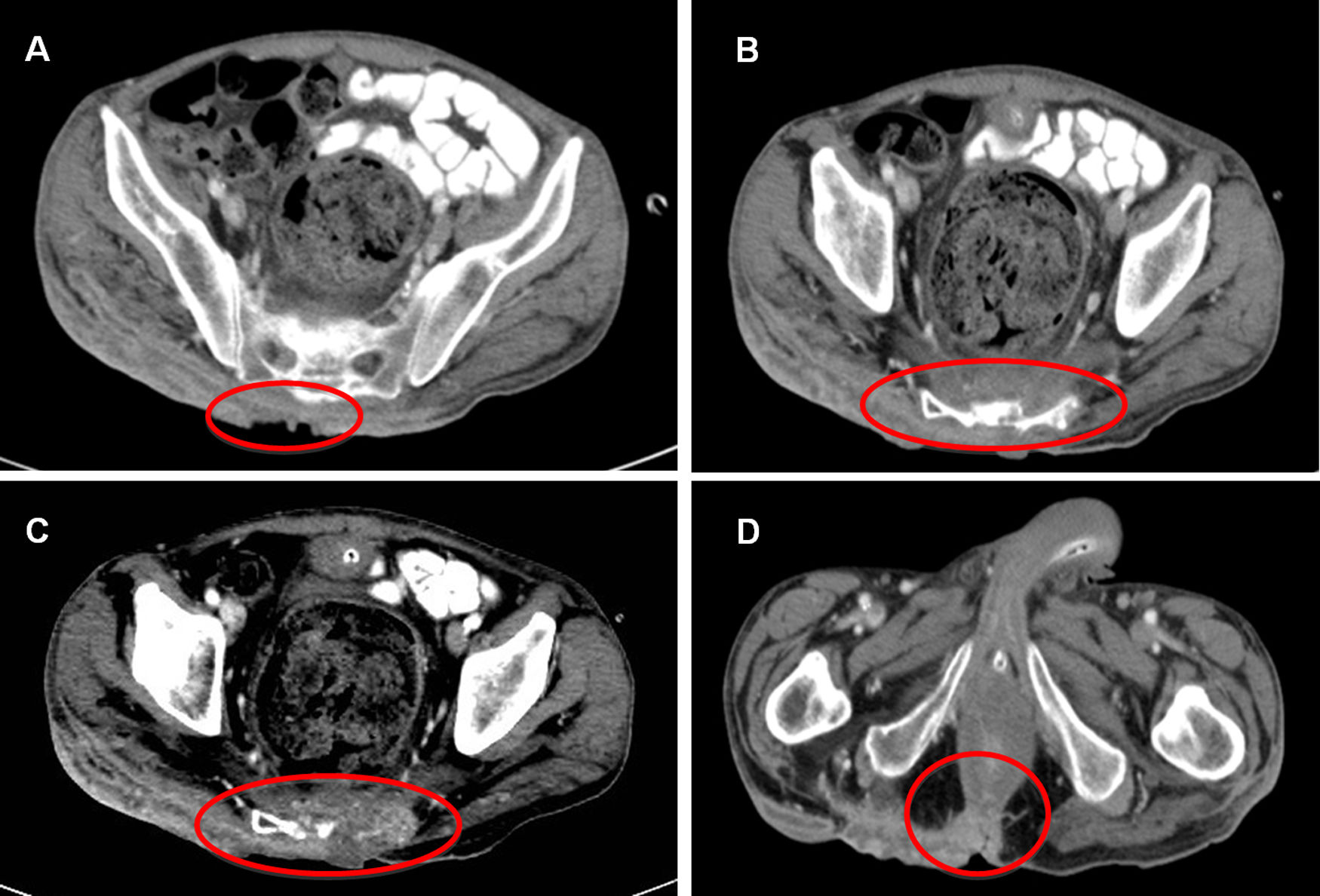

Abdominal CT scan showed extensive involvement of the subcutaneous tissue from approximately L4 to the coccyx, with erosion of the sacrum and destruction of the coccyx. In one area, the external anal sphincter was also involved on the posterior side (Fig. 2A–D).

With the diagnosis of sacral infiltration secondary to well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, and after multidisciplinary assessment, we decided to initiate palliative treatment given the large extent of the tumor and the poor physical state of the patient (Karnofsky index: <50). The patient was hospitalized and died in less than 4 months.

The mechanisms by which this malignization occurs are still not well understood, although it has been suggested that the sustained chronic inflammation of the tissues leads to alterations in cell replication and may end up causing the mutation necessary to generate cancer. This form of malignant transformation would be shared by some other diseases or situations where there may be chronic inflammation, such as the presence of long-term stomata4 or Marjolin ulcers.5 Some other options have been postulated, such as the presence of the human papillomavirus (HPV), given its relationship with the perianal, perineal, inguinal and gluteal regions, which have not been universally accepted.6

Although we do not know the mechanisms, the most important risk factors have been well established, including male sex, gluteal and perineal location and the progression of the disease over an extended period of time.6 All of these factors were present in our patient. Some authors emphatically insist that a more vigilant and aggressive approach should be maintained in these cases to avoid this risk.7

Once malignant transformation has occurred, the ideal treatment is surgical, with wide resection margins and special attention to possible subcutaneous extension. In spite of radical treatment, the prognosis is ill-fated in most cases, with 2-year mortality rates between 23% and 57%, even in the absence of disseminated disease.8 Given the poor prognosis of the disease, despite very aggressive surgical treatments, a palliative approach in certain cases is not unusual.8

Given the most frequent location of these tumors in the buttocks and perineum, the invasion of pelvic bone structures is relatively frequent, as in our patient.

The effect of radiotherapy on these tumors is minimal, but its palliative use to control symptoms such as pain from the invasion of deep tissues is still feasible.9 In our case, we could not offer our patient this option because of his poor general condition.

In short, hidradenitis suppurativa is a chronic disease with a poor response to treatment that is often met with a certain degree of resignation from patients and doctors, as well as a certain degree of abandonment. However, we must be aware that there is a risk of developing squamous cell carcinoma, mainly in young patients who have a long period of disease progression ahead of them, mostly males, and in perianal, perineal and gluteal locations. In this context, we recommend more aggressive management of the disease, especially those cases that meet the high-risk criteria mentioned, in order to try to minimize the incidence of this type of tumors with such a severe prognosis.

Please cite this article as: Cerdán Santacruz C, Santos Rancaño R, Díaz del Arco C, Ortega Medina L, Cerdán Miguel J. Carcinoma escamoso sobre hidrosadenitis supurativa perineal. Cir Esp. 2019;97:602–604.