Surgical treatment of oesophagogastric junction adenocarcinomas is based on total gastrectomies or oesophagectomies, which are complex procedures with potentially high morbidity and mortality. Population-based registers show a considerable variability of protocols and outcomes among different hospitals and regions. One of the main strategies to improve global results is centralization at high-volume hospitals, a process that should take into account the benchmarking of processes and outcomes at referral hospitals. Minimally invasive surgery can improve postoperative morbidity while maintaining oncological guaranties, but is technically more demanding than open surgery. This fact underlines the need for structured training and mentorship programs that minimize the impact of surgical teams’ training curves without affecting morbidity, mortality or oncologic radicality.

El tratamiento quirúrgico de los adenocarcinomas de la unión esofagogástrica se basa en gastrectomías totales o esofaguectomías oncológicas, procedimientos de alta complejidad y considerable morbimortalidad. Los datos obtenidos del análisis de registros quirúrgicos poblacionales muestran una elevada variabilidad en el enfoque terapéutico y los resultados entre diferentes centros hospitalarios y zonas geográficas. Una de las principales medidas destinadas a reducir esta variabilidad, mejorando los resultados globales, es la centralización de la enfermedad en centros de referencia, proceso que debe basarse en el cumplimiento de unos estándares de calidad e ir acompañada de la armonización de protocolos terapéuticos. La cirugía mínimamente invasiva puede disminuir la morbilidad postoperatoria sin comprometer la supervivencia, pero es técnicamente más demandante que la cirugía abierta. Los programas de formación quirúrgica tutelada permiten incorporar la cirugía mínimamente invasiva a la práctica de los equipos quirúrgicos sin que la curva de aprendizaje condicione la morbimortalidad ni la radicalidad oncológica.

Oesophagogastric junction (OGJ) adenocarcinomas are tumours of increasing incidence in Western countries, whose treatment is based on a multimodal approach with chemotherapy, radiotherapy and surgery.1,2 Surgery continues to be the only treatment with curative intent, based on extended total gastrectomies or oncological oesophagectomies, which are highly complex procedures with considerable morbidity and mortality. Current data show significant variability in the approach and results of neoadjuvant, surgical and adjuvant treatment of OGJ tumours among different hospitals and geographical areas.3 To minimize this variability and improve overall results, several countries have promoted centralization processes at reference hospitals in recent decades, with globally positive results.4,5 In addition, with the introduction of minimally invasive surgical procedures that are technically more demanding, the need for standardized training for surgeons from oesophagogastric surgery units has become apparent so that their learning curve is not detrimental to oncological radicality and patient safety.6

This article reviews the heterogeneity in the therapeutic approach and the results of the treatment of OGJ tumours according to data from population registries. Standardization initiatives for centralized disease management and surgical training are also discussed.

CentralizationSurgical treatment of tumours in the oesophagus and OGJ is associated with considerable postoperative morbidity and mortality as well as low survival.3,7 Several studies have shown that these results are better in high-volume hospitals,8–15 although there is no consensus.16 In a 2012 meta-analysis, Wouters et al.9 analyzed 32 articles that demonstrated the inverse relationship between hospital volume and postoperative mortality after oesophagectomy (OR 2.30, 95%CI 1.89–2.80), while 7 established an association between hospital volume and survival (OR 1.17, 95%CI 1.05–1.31). However, many of these studies were observational and based on administrative data, and it has been stressed that the positive effects of higher hospital volume are less pronounced in prospective studies than in retrospective studies.17 In any case, no study has shown worse results at high-volume hospitals. Consequently, there have been several proposals for a minimum recommended annual volume per hospital: Henneman et al.13 demonstrated that Dutch surgical teams that performed more than 40 oesophagectomies per year had a lower 6-month mortality (HR 0.73, 95%CI 0.65–0.83) and 2-year mortality (HR 0.88, 95%CI 0.83–0.93), so they considered that this should be the minimum number required for a specialized surgical team. Following a similar method, other authors have established cut-off points at a minimum of 13 or 20 oesophagectomies per year.18,19

These findings have justified the implementation of different centralization processes for carcinoma of the oesophagus and the OGJ. Vonlanthen et al.17 analyzed the centralized care policies for cancer surgery in 20 European countries, USA and Canada, finding that the majority (15 out of 22) had defined a minimum annual volume of oesophagectomies per hospital, with a very wide range from 7 in Canada to 80 in Denmark. In 2 countries (United Kingdom and USA), a minimum volume per surgeon was also proposed. However, these measures were legally imposed in only 6 countries. These centralization processes have demonstrated their effectiveness in countries such as the Netherlands, where postoperative mortality was reduced from 12% to 5% (P=.003) and hospital stay from 21 to 17 days (P=.002), increasing the 2-year survival from 38% to 54% (P=.001).5

Most of these initiatives do not consider OGJ tumours as a separate case and are based on the definition of the type of surgical resection. In oncological gastrectomies, the correlation between hospital volume and postoperative mortality, the extension of the lymphadenectomy and long-term survival has also been described, although less significantly than with oesophagectomies.14,17 Some countries have also promoted processes to centralize gastrectomies, with good results, such as Denmark, where the anastomotic dehiscence rate decreased from 6.1% to 5% (HR 5.2, 95%CI 3.2–7.7), 30-day mortality from 8.2% to 2.4% (HR 2.8, 95%CI 1.2–4.4) and the percentage of patients with at least 15 resected lymph nodes from 19% to 76% (P<.001).20

In Spain, several autonomous communities have carried out centralization processes for oesophagogastric cancer in recent years in a more or less spontaneous or directed manner. In the first decade of this century, the number of hospitals authorized to perform this surgery in Catalonia decreased from 69 to 17, with the consequent increase in oesophagectomies and gastrectomies per hospital and year (from 3.4 to 7.4 and from 7.2 to 17, respectively). A decrease in postoperative morbidity and mortality was observed, together with an increase in transthoracic access and extended lymph node dissections, as well as a greater uniformity of multimodal treatments.21,22 Recently, the regional government of Catalonia has established a minimum of 11 gastrectomies and 11 oesophagectomies per year to authorize a hospital to treat oesophagogastric epithelial neoplasms with radical intent.

But centralization policies based exclusively on hospital volume may not translate into an optimal benefit, since there are other factors that play an important role.17,20 This was demonstrated by Simunovic et al.,23 comparing the results of the regionalization of pancreatic cancer treatment in 2 provinces of Canada, where they implemented different quality care measures, with very different results. In addition, the choice of referral hospital should not be based only on the number of annual procedures performed by each hospital at the time of initiating the centralization process, but above all on compliance with the requirements for structure, processes and results.17,24 Low et al.25 defined the postoperative reference results (benchmarking) that would be reasonable to require from a specialized surgical unit, based on the rates of complications, mortality and readmissions of 2704 oesophagectomies from the registry promoted by the Oesophageal Complication Consensus Group. Recently, new concepts have been described, such as the Failure to Rescue (percentage of patients with a postoperative complication who die as a result) and the Textbook Outcome (percentage of patients who meet a series of ideal perioperative results), which are also criteria of hospital care quality.26,27 Some authors and institutions, such as the European CanCer Organization, have developed lists of the structural resources and quality parameters required to perform oncological gastrectomies and oesophagectomies according to published evidence: the number of patients treated per year is only one of those factors, together with many others such as hospital structure, staff training, surgical radicalism, postoperative morbidity and mortality rates, compliance with multimodal protocols and participation in audited multicentre registries.28–30

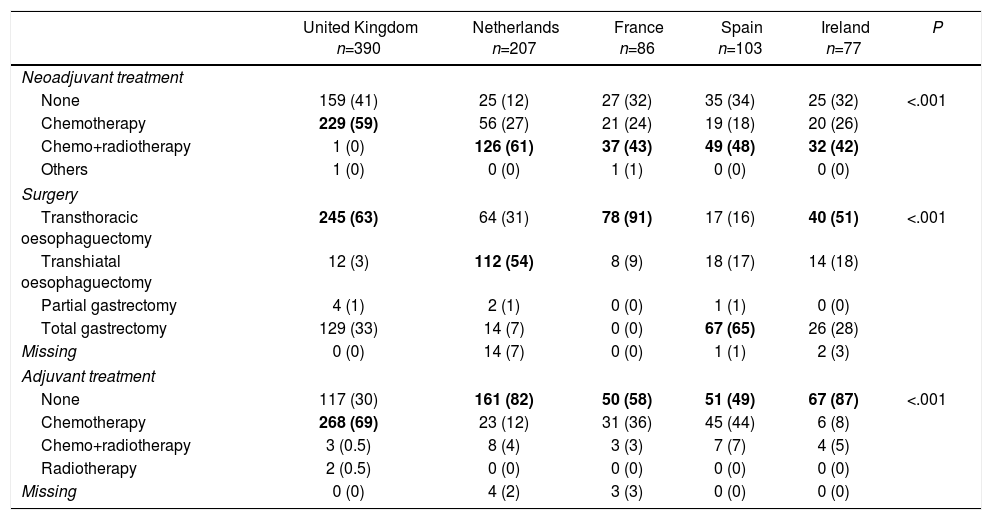

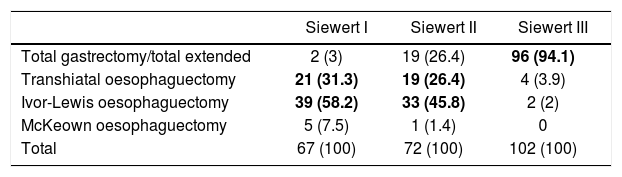

RegistriesOncological registries are useful to identify differences in the presentation of the disease and compare therapeutic approaches and outcomes among different geographic areas and hospitals.3,31,32 A comparative study of 5 clinical population registries within the EURECCA project identified large variations in the therapeutic approach of patients with OGJ tumours: in the United Kingdom the majority received neoadjuvant chemotherapy (59%), while in the Netherlands chemoradiotherapy was the most frequent regimen (54%). The most common surgical resection was transthoracic oesophagectomy in France (91%) and England (63%), while in Spain more total extended gastrectomies (65%) were recorded (Table 1). These differences can be explained in part by the tumour location and the degree of preparation of the team in thoracic surgery. The Spanish EURECCA registry recently analyzed 2024 patients operated on between 2014 and 2017, 241 of which (12%) were OGJ surgeries. More total extended gastrectomies were indicated in Siewert III type tumours (94%); meanwhile, in Siewert I and II, more Ivor-Lewis (52%) and transhiatal (28%) oesophagectomies were performed (Table 2). Regarding neoadjuvant treatment, most patients with Siewert III type tumours received chemotherapy (44%) or initial surgery (41%), while in Siewert I and II, chemoradiotherapy was indicated more frequently (52%) (Table 3). The Dutch registry analyzed 266 resectable OGJ tumours, 86% of which were treated by oesophagectomy and 14% by gastrectomy. In patients with Siewert II tumours (n=176), gastrectomies were associated with a greater risk of involvement of the oesophageal circumferential margin (29 vs 11%, P=.025) and more limited lymphadenectomies (5 vs 34%, P<.001).33

Variability in the Therapeutic Approach of Oesophagogastric Junction Tumours in Different National Registries.

| United Kingdom n=390 | Netherlands n=207 | France n=86 | Spain n=103 | Ireland n=77 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neoadjuvant treatment | ||||||

| None | 159 (41) | 25 (12) | 27 (32) | 35 (34) | 25 (32) | <.001 |

| Chemotherapy | 229 (59) | 56 (27) | 21 (24) | 19 (18) | 20 (26) | |

| Chemo+radiotherapy | 1 (0) | 126 (61) | 37 (43) | 49 (48) | 32 (42) | |

| Others | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Surgery | ||||||

| Transthoracic oesophaguectomy | 245 (63) | 64 (31) | 78 (91) | 17 (16) | 40 (51) | <.001 |

| Transhiatal oesophaguectomy | 12 (3) | 112 (54) | 8 (9) | 18 (17) | 14 (18) | |

| Partial gastrectomy | 4 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Total gastrectomy | 129 (33) | 14 (7) | 0 (0) | 67 (65) | 26 (28) | |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 14 (7) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | |

| Adjuvant treatment | ||||||

| None | 117 (30) | 161 (82) | 50 (58) | 51 (49) | 67 (87) | <.001 |

| Chemotherapy | 268 (69) | 23 (12) | 31 (36) | 45 (44) | 6 (8) | |

| Chemo+radiotherapy | 3 (0.5) | 8 (4) | 3 (3) | 7 (7) | 4 (5) | |

| Radiotherapy | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 4 (2) | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

Values expressed as n (%). The most frequent variables for each case are highlighted in bold.

Adapted from Messager et al.,3 with permission.

Results From the Spanish EURECCA Registry 2014–2017: Surgical Technique Indicated for Tumours of the Oesophagogastric Junction According to Locations (n=241) (Unpublished Data).

| Siewert I | Siewert II | Siewert III | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total gastrectomy/total extended | 2 (3) | 19 (26.4) | 96 (94.1) |

| Transhiatal oesophaguectomy | 21 (31.3) | 19 (26.4) | 4 (3.9) |

| Ivor-Lewis oesophaguectomy | 39 (58.2) | 33 (45.8) | 2 (2) |

| McKeown oesophaguectomy | 5 (7.5) | 1 (1.4) | 0 |

| Total | 67 (100) | 72 (100) | 102 (100) |

Values expressed as n (%). The most frequent variables for each case are highlighted in bold.

Results From the Spanish EURECCA Registry, 2014–2017: Neoadjuvant Treatment Indicated for Tumours of the Oesophagogastric Junction According to Locations (n=241) (Unpublished Data).

| Siewert I | Siewert II | Siewert III | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial surgery | 19 (28.3) | 22 (30.6) | 42 (41.2) |

| Radiotherapy+chemotherapy | 37 (55.2) | 35 (48.6) | 15 (14.7) |

| Radiotherapy | 2 (3) | 0 | 0 |

| Chemotherapy | 9 (13.5) | 15 (20.8) | 45 (44.1) |

| Total | 67 (100) | 72 (100) | 102 (100) |

Values expressed as n (%). The most frequent variables for each case are highlighted in bold.

However, there are differences in the nature of the registries that may limit the interpretation and comparison of the data. For instance, only in certain countries are registries mandatory and financed with public resources: DUCA (Holland), FREGAT (France) and NOGCA (England and Ireland). In other countries, they are occasional and voluntary or non-existent.34–36 The items collected are not always well defined or standardized to facilitate comparisons.37 In addition, only 2 of them (DUCA and the NREV in Sweden) have been audited to validate the reliability of the data.34,38

In Spain, the EURECCA gastro-oesophageal cancer registry began in 2013 in Catalonia and Navarra, taking advantage of the centralization of the disease. It is a population and clinical registry, which is not administrative as in previous publications.22,39 In 2015, the Basque Country was incorporated and subsequently La Rioja, coinciding with the online launch of the registry and the more precise, standardized definition of the items, following the consensus recommendations of international groups.7,40–43 Today, 30 hospitals from 4 regions of Spain participate in the Spanish EURECCA registry and an audit is underway, following the Swedish NREV model, to ensure the accuracy and consistency of the data.38

TrainingIt is impossible to contemplate the process of centralizing care for an oncological pathology without facing the new challenges of the referral hospitals. The surgical and multimodal treatment of OGJ tumours is complex, which requires specific training of the teams involved.17 The Union Européene des Médicins Spécialistes (www.uems.eu) recommends that specialized postgraduate training be accredited, including stays at qualified medical centres (fellowships) and exams. Both the American College of Surgeons (http://www.facs.org/education/resources/medical-students/postres) and the European Society of Surgical Oncology (https://www.essoweb.org/fellowships/training-fellowships/) promote training programs that include fellowships of one or 2 years and seek to ensure competency in indication, surgical technique, management of complications and research.

The training of surgical teams should not be short-lived, but instead it should be continuous and adapt to technological advances. Minimally invasive surgery (MIS) has been gaining space in recent years in the treatment of oesophageal and OGJ cancer.44–47 However, it is technically more complex than open surgery and is associated with a learning curve, during which oncological radicality can be compromised, increasing postoperative morbidity and the rate of reinterventions.48–51 Mentorship or proctorship programs aim to minimize the impact on the patient of these learning curves in MIS through a process of progressive and tutored involvement of surgeons before functioning autonomously. Nevertheless, oncological radicalism and patient safety must always take precedence over the type of approach.

In 2003, a national training program for robot-assisted minimally invasive oesophagectomies (RAMIE) was initiated in the Netherlands. First, surgical time, blood loss and conversion rate of the “mentors” were prospectively studied, and the authors assessed how many interventions were required for these parameters to reach equal or above-average values. The mentor learning curve was completed after 70 procedures in 5 years. In a second phase, the “students” were incorporated successively, first as observers and then as the mentors’ assistants, to later become assisted by the mentors and, finally, working autonomously under supervision. The students’ learning curve required 24 procedures in one year, 70% less than the mentors who helped and supervised them.6

In Spain, the EURECCA registry has shown that only 37% of gastrectomies and 41% of oesophagectomies are performed as MIS (unpublished data). The Spanish EURECCA group created a training committee that has designed a program based on the “clinical immersion” format, which combines live surgery with interactive clinical sessions, aimed at surgeons experienced in open surgery of the stomach, oesophagus and OGJ, who desire training in or improving MIS techniques. This initiative is based on the assumption that the initiated team will carry out a minimum number of annual procedures that will guarantee its continuity. The objective of this and other training programs should be that patients can benefit from the advantages of MIS without the learning curve of the surgical team compromising patient safety or survival.

In conclusion, multicentre surgical registries are able to identify the variability in the processes and results of OGJ tumour treatment. One of the main measures aimed at reducing this variability and improving overall results is the centralization of disease management at referral hospitals, a process that should be based on compliance with quality standards by specialized units and be accompanied by the harmonization of therapeutic protocols. In the hands of experienced surgeons, MIS can decrease postoperative morbidity without compromising survival, but it is technically more demanding. Mentored surgical training programs allow for MIS to be incorporated into the practice of referral hospital teams without the learning curve affecting morbidity and mortality rates or oncological radicalism.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Spanish EURECCA Group for oesophagogastric cancer.

Please cite this article as: Osorio J, Rodríguez-Santiago J, Roig J, Pera M. Proyectos de estandarización del tratamiento del cáncer de la unión esofagogástrica: centralización, registros y formación. Cir Esp. 2019;97:470–476.