Laparoscopic surgery is the gold standard treatment of symptomatic gallstones. For some, it is also the treatment of choice for choledocholithiasis. Certain special and rare circumstances regarding the number, size and location of bile duct stones or altered bile duct anatomy (embryonic or acquired), can be challenging to resolve with usual laparoscopic techniques. For these situations, we describe 10 surgical strategies that are relatively simple and inexpensive to apply, making them appropriate to be used in most surgical centers.

El abordaje laparoscópico es el método de elección para el tratamiento de la litiasis vesicular sintomática, y para muchos también lo es para la coledocolitiasis. Algunas situaciones especiales e infrecuentes en el tamaño, número y ubicación de los cálculos o en alteraciones de la anatomía biliar embriológicas o adquiridas pueden generar dificultades para la resolución de estas afecciones con técnicas laparoscópicas habituales. Para estas situaciones describimos 10 estrategias quirúrgicas de aplicación relativamente sencilla y que requieren de escasos recursos económicos, por lo que creemos que pueden adaptarse a la mayor parte de los centros quirúrgicos.

For decades, the laparoscopic approach has been the gold standard for the treatment of gallstones, and currently also for choledocholithiasis.1

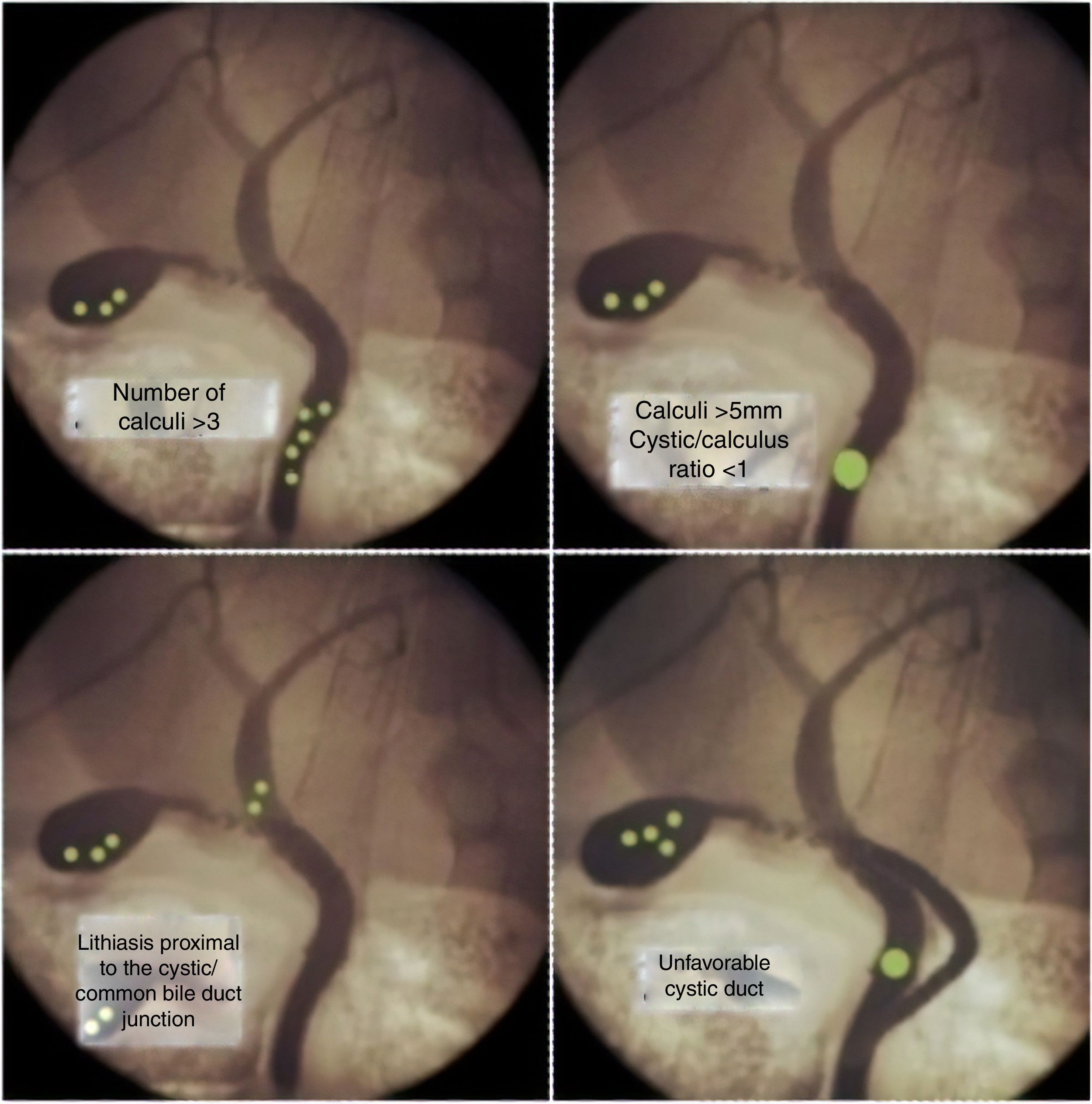

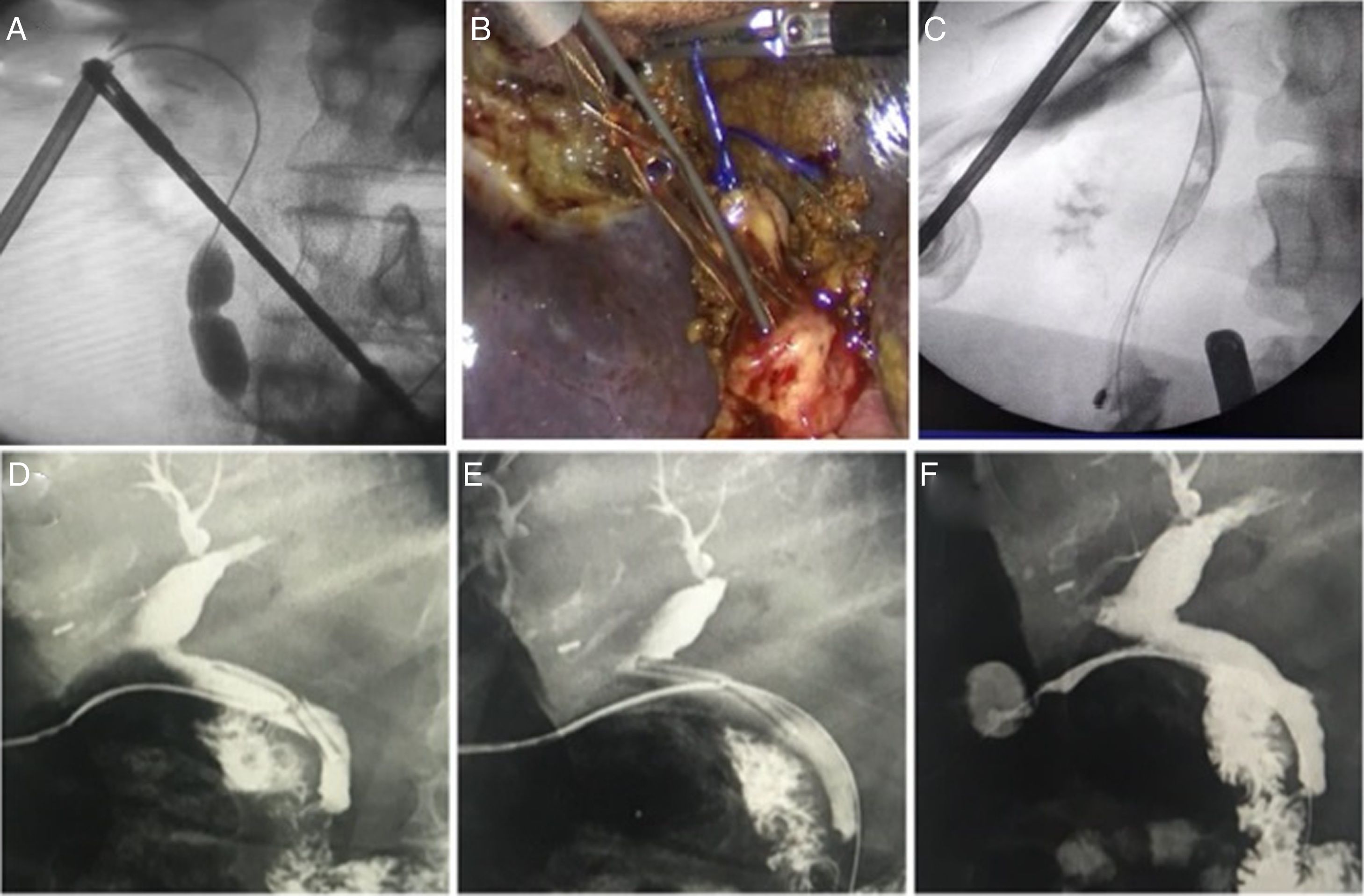

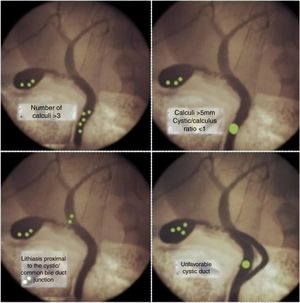

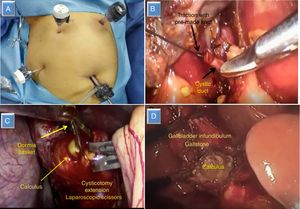

When inflammation alters the normal anatomy of Calot’s triangle, or rare conditions occur associated with the choledocholithiasis, resolution can be difficult. Unfavorable situations may be related to the size, number and location of the stones or anatomical variables of the biliary tree2–4 (Fig. 1).

The objective of this study is to describe techniques used in our department to try to improve the efficacy of laparoscopic biliary surgery in unfavorable situations.

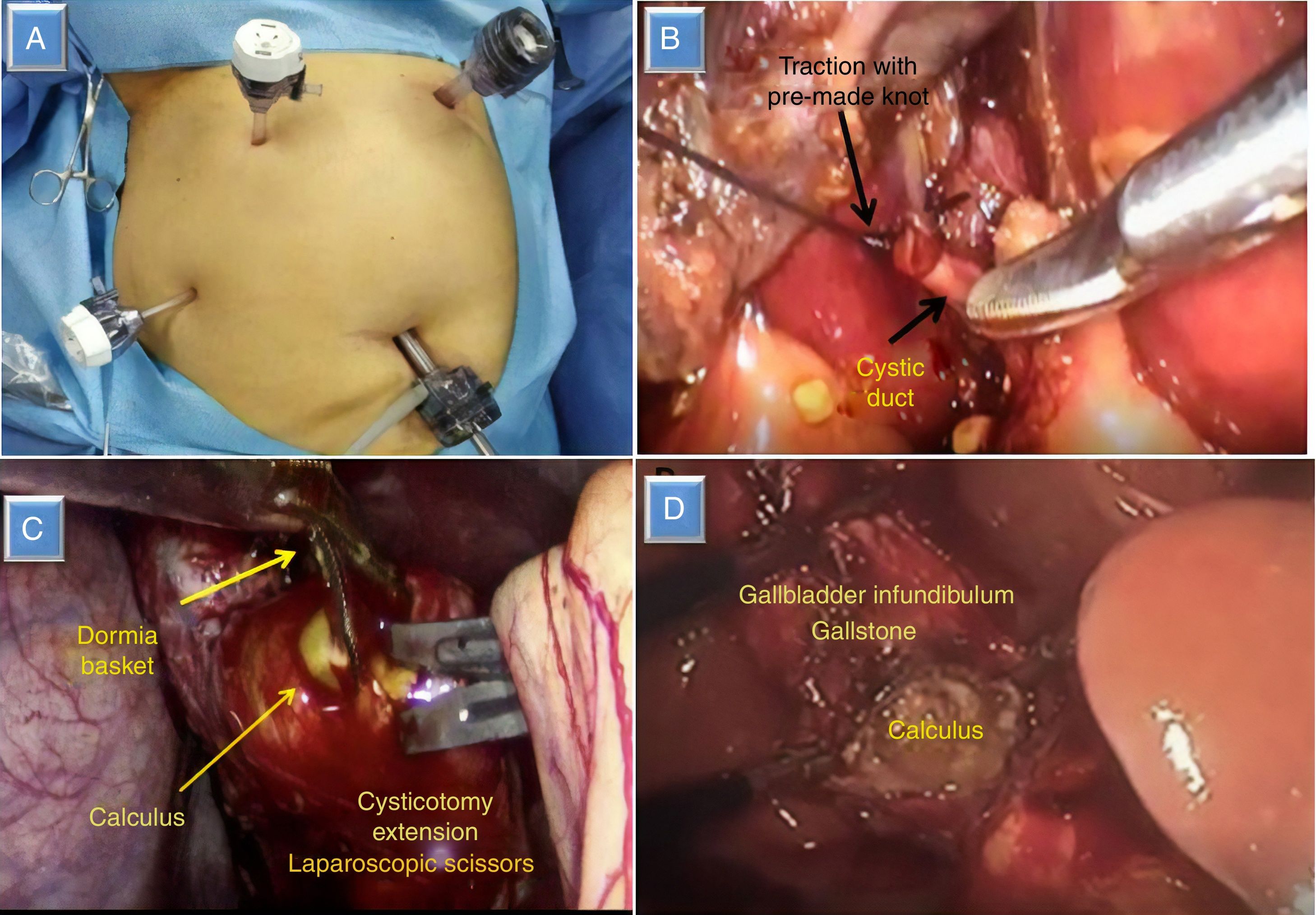

Surgical techniqueModified port placementWe use the classic American location of the ports for laparoscopic cholecystectomy, with the surgeon standing to the left of the patient. In cases where we suspect choledocholithiasis, and in anticipation of the need to perform intracorporeal stitches, we believe that the optimal location of the epigastric port is to the left of the midline and the round ligament, in the left hypochondrium, which provides better angulation for advanced maneuvers (Fig. 2A).

Cystic duct ligation and new cysticotomyWhen faced with involuntary total division of the cystic duct after cysticotomy, it is often difficult to grasp with forceps in order to insert a cholangiography catheter or a basket, especially when the residual length is short. A simple way to solve this is to ligate the divided duct with a pre-made endoloop knot, pulling it to perform a new cysticotomy and subsequent reinsertion of a catheter (Fig. 2B).

Enlargement of cysticotomy over a calculusWhen the cystic duct/calculus ratio is <1 (meaning that the diameter of the cystic duct is smaller than the choledochal calculus), the potential success of transcystic instrumentation is drastically lower.4

The maneuver we use involves snaring the stone with the basket, dragging it to the cystic duct, and expanding the cysticotomy over the stone (Fig. 2C).

Opening of gallbladder and extraction of a stone embedded in the infundibulumAdequate traction of the infundibulum of the gallbladder is one of the requirements for a safe cholecystectomy.5,6 When a large calculus completely occupies it, adequate traction is difficult and is a limitation to achieve the critical view of safety, increasing the conversion rate.5

Opening the gallbladder on the surgical side allows for the stone to be removed and adequate traction is achieved (Fig. 2D). In some cases, this maneuver can create an added complication as stones can fall into the peritoneal cavity, so we only use it in selected cases of great difficulty, such as Mirizzi syndrome type I.

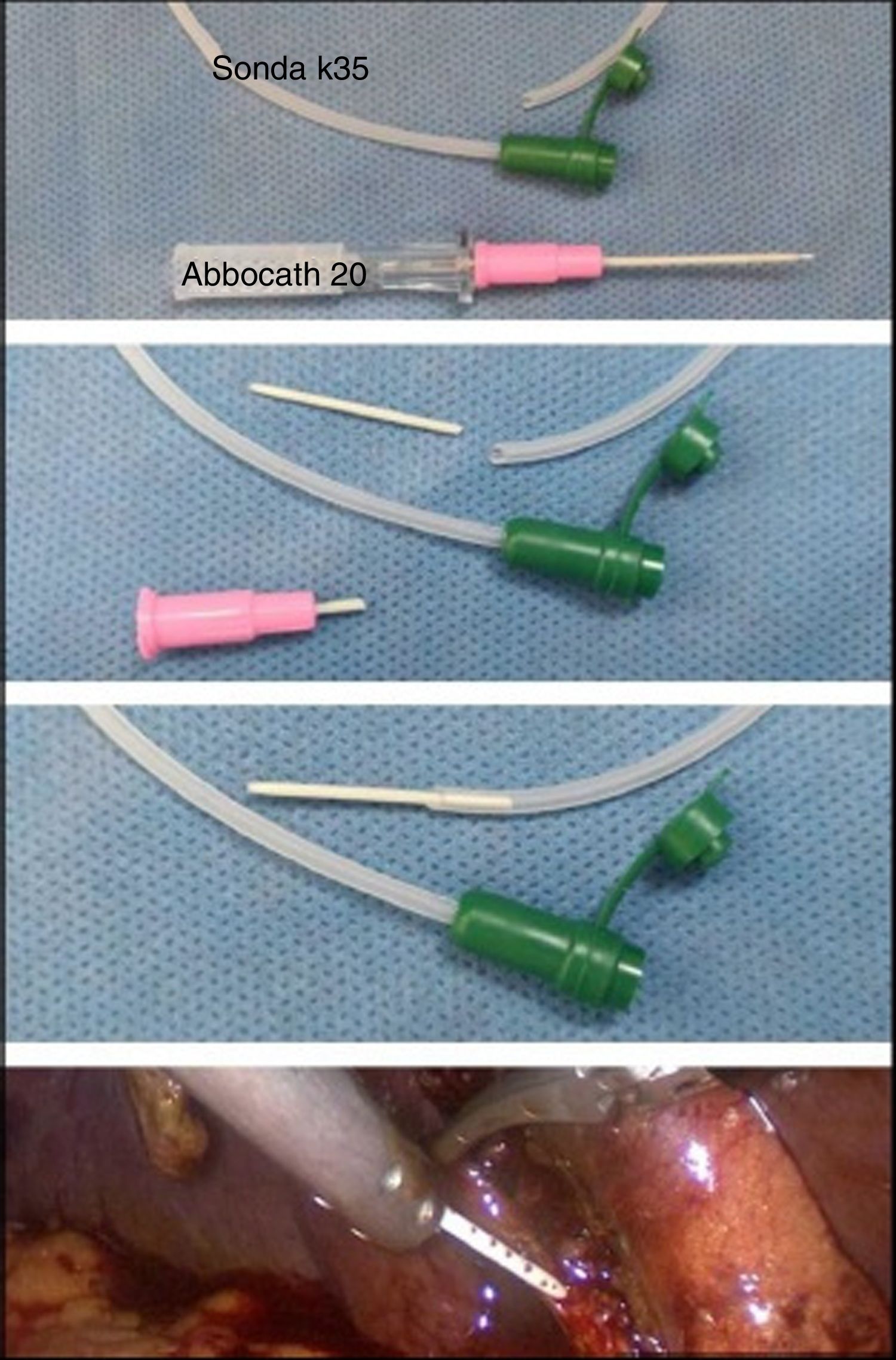

Reduction of the cholangiography catheter caliberWhen the diameter of the cystic duct is smaller than that of the catheter used for intraoperative cholangiography, a maneuver we perform is the insertion of the plastic cap of an Abbocath-type catheter into the lumen of the cholangiography catheter. When introducing it into the cysticotomy, we use atraumatic forceps so that no leaks occur that would interfere with the sharpness of the image (Fig. 3). This resource was necessary in very few cases, but it enabled us to achieve intraoperative cholangiography in 100%.

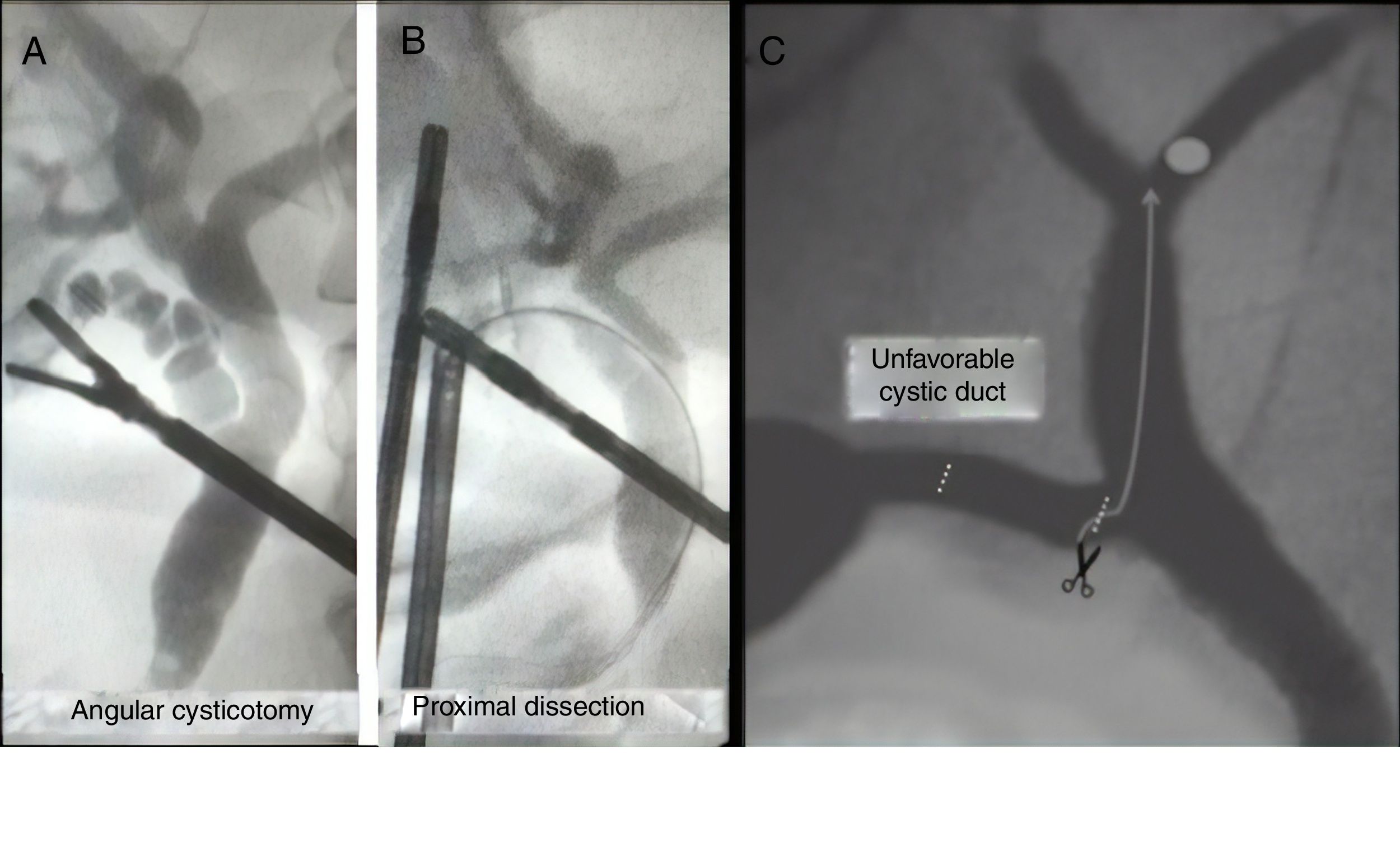

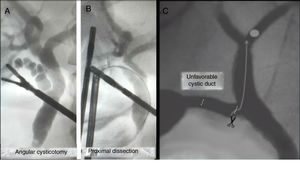

New dissection of the cystic ductAdequate dissection of the cystic duct provides a critical view of safety. However, in unfavorable cystic ducts (twisted or presenting cystic duct stones7,8), it is difficult to perform intraoperative cholangiography, and even more so transcystic instrumentation.

In these cases, a new dissection of the duct closest to the main bile duct is necessary, allowing us to straighten the pathway and perform a new cysticotomy while facilitating canalization and subsequent instrumentation (Fig. 4A and B).

Angular cysticotomy or minimal choledochotomyThe presence of intrahepatic stones is uncommon, and even more so is the impossibility of descending them beyond the cystic-choledochal junction. When faced with this exceptional situation, we perform a new cysticotomy on the lower side, close to the junction, which allows us to direct the basket snare towards the intrahepatic bile duct.9

In some cases, closure must be performed with stitches due to the proximity with the main bile duct (Fig. 4C).

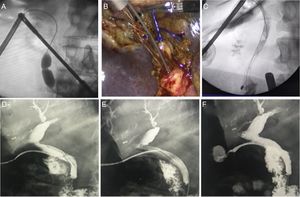

Progressive antegrade papillary dilation controlled with percutaneous balloonUnder imaging guidance, we insert a percutaneous dilatation balloon over a 0.035” hydrophilic guidewire (Roadrunner-Cook Medical®) through the cystic duct, positioning it in the papilla. Dilation is conducted progressively using balloons (Quantum TTC-Cook Medical®) of 8mm–20mm in diameter for 20s to a pressure of 6atm. We have registered no morbidity with the use of hydrophilic guidewire and no false pathways. We use this strategy in the following situations:

- -

Choledochorrhaphy: after complete removal of the calculi by choledochotomy, and in cases with unsatisfactory or uncertain papillary evacuation, we perform papillary balloon dilation and primary closure of the common bile duct. The goal of dilation is to decrease intracholedochal pressure during the healing period and to avoid placing a T-tube or antegrade stent.

- -

Total acute choledochal occlusion syndrome: this uncommon and adverse situation occurs when a calculus is embedded in the mid or distal common bile duct, preventing the passage of contrast material and the basket into the duodenum. Treatment consists of trying to pass a guidewire into the duodenum to introduce a percutaneous balloon, which dislodges the stone for later extraction with a basket or progression to the duodenum10 (Fig. 5A).

In cases of total acute choledochal occlusion syndrome, a maneuver that we use prior to antegrade papillary dilation is the insertion of a hydrophilic 0.035” guidewire (Roadrunner-Cook Medical®) and a Dormia basket in parallel or in tandem. The wire is able to pass between the bile duct and the stone, achieving mobilization, after which the basket is used for extraction (Fig. 5B and C).

T-tube removal with guidewireThe T-tube is extracted 6–8 weeks after its placement and after having performed a fistulogram 10 days after surgery to confirm the absence of lithiasis and correct papillary drainage. The main complication of its removal is the rupture of the tract and posterior leakage or choleperitoneum. To avoid this, we insert a 0.035” hydrophilic guidewire (Roadrunner-Cook Medical®) through the T-tube to the duodenum under fluoroscopy, and then remove the tube, leaving the wire in the duodenum. We corroborate the integrity of the tract by performing a fistulogram through the cutaneous orifice. Then, the procedure is either concluded if there are no leaks, or a catheter is placed with the wire as a guide if there was contrast leakage due to rupture (Fig. 5D–F).

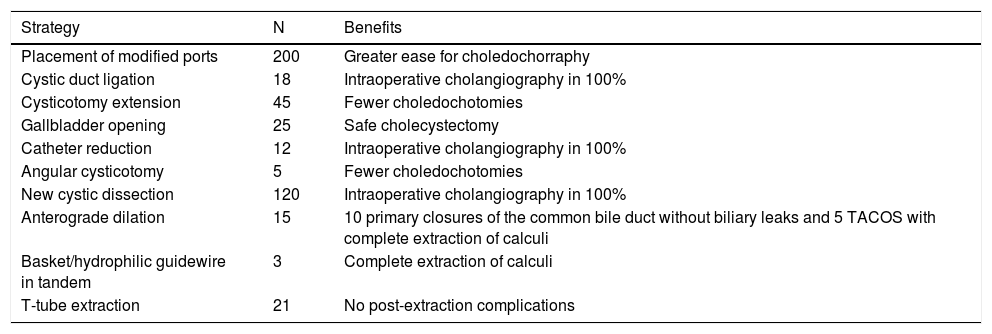

DiscussionThe 10 strategies we have presented could be useful to improve the effectiveness of the laparoscopic approach in complex and uncommon situations, minimizing intraoperative and postoperative complications. They have arisen over 20 years of experience in laparoscopic surgery at a referral center for complex biliary disease and were developed respecting the precepts of surgical safety (Table 1).

Results of strategies to improve the efficacy of laparoscopic biliary surgery.

| Strategy | N | Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Placement of modified ports | 200 | Greater ease for choledochorraphy |

| Cystic duct ligation | 18 | Intraoperative cholangiography in 100% |

| Cysticotomy extension | 45 | Fewer choledochotomies |

| Gallbladder opening | 25 | Safe cholecystectomy |

| Catheter reduction | 12 | Intraoperative cholangiography in 100% |

| Angular cysticotomy | 5 | Fewer choledochotomies |

| New cystic dissection | 120 | Intraoperative cholangiography in 100% |

| Anterograde dilation | 15 | 10 primary closures of the common bile duct without biliary leaks and 5 TACOS with complete extraction of calculi |

| Basket/hydrophilic guidewire in tandem | 3 | Complete extraction of calculi |

| T-tube extraction | 21 | No post-extraction complications |

TACOS: total acute choledochal obstruction syndrome.

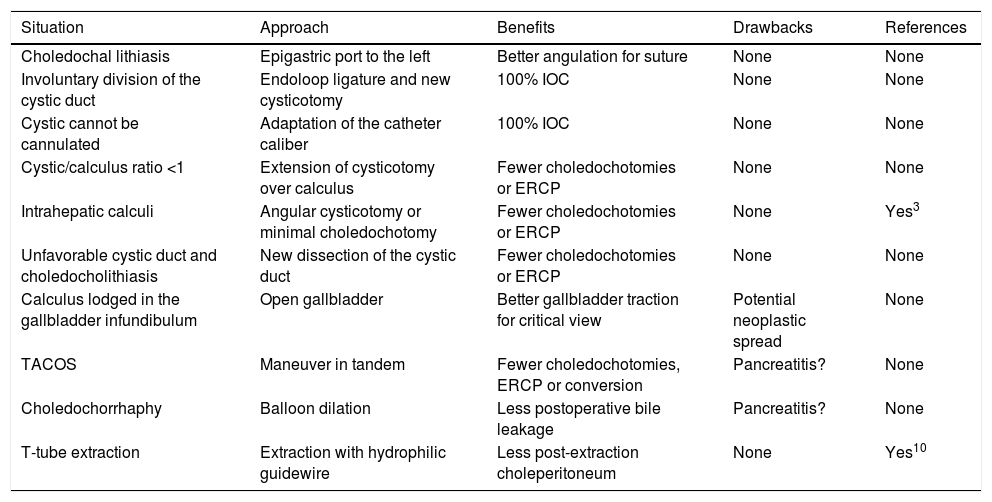

It would be difficult to compare these strategies with the literature available, and this would also exceed the objective of this paper. Nonetheless, we have found citations for only 3 of these approaches (angulated cysticotomy, antegrade papillary dilation and T-tube extraction).9–11

With regard to angulated cysticotomy and minimal choledochotomy, we found a publication for the resolution of choledocholithiasis in elderly patients that the authors used for the introduction of a choledochoscope, while we used it to direct a Dormia basket to the intrahepatic bile duct.9

Existing publications on antegrade papillary dilation evaluate its role in the management of choledocholithiasis and how to improve the effectiveness of the laparoscopic approach to achieve complete extraction. This is usually achieved by passage of multiple stones through the dilated papilla. We did not find any publications referring to its use in reducing bile leaks in the event of primary closure of the common bile duct in patients with delayed papillary evacuation. We believe that papillary dilation is a valid strategy to improve papillary evacuation, thereby avoiding the placement of a T-tube or an antegrade stent, which would later require endoscopy for its extraction10 (Table 2).

Utility and benefits of strategies to improve laparoscopic biliary surgery.

| Situation | Approach | Benefits | Drawbacks | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choledochal lithiasis | Epigastric port to the left | Better angulation for suture | None | None |

| Involuntary division of the cystic duct | Endoloop ligature and new cysticotomy | 100% IOC | None | None |

| Cystic cannot be cannulated | Adaptation of the catheter caliber | 100% IOC | None | None |

| Cystic/calculus ratio <1 | Extension of cysticotomy over calculus | Fewer choledochotomies or ERCP | None | None |

| Intrahepatic calculi | Angular cysticotomy or minimal choledochotomy | Fewer choledochotomies or ERCP | None | Yes3 |

| Unfavorable cystic duct and choledocholithiasis | New dissection of the cystic duct | Fewer choledochotomies or ERCP | None | None |

| Calculus lodged in the gallbladder infundibulum | Open gallbladder | Better gallbladder traction for critical view | Potential neoplastic spread | None |

| TACOS | Maneuver in tandem | Fewer choledochotomies, ERCP or conversion | Pancreatitis? | None |

| Choledochorrhaphy | Balloon dilation | Less postoperative bile leakage | Pancreatitis? | None |

| T-tube extraction | Extraction with hydrophilic guidewire | Less post-extraction choleperitoneum | None | Yes10 |

IOC: intraoperative cholangiography; ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; TACOS: total acute choledochal obstruction syndrome.

Regarding the removal of the T-tube, there is a management strategy for immunocompromised patients in which the authors inject contrast through the skin lateral to the tube in order to verify the integrity of the tract prior to extraction. If it is not undamaged, they repeat the procedure 2 weeks later.11 We believe that our strategy would make it possible to treat the rupture of the tract immediately and without delay, and always after and not before the removal of the T-tube. The use of a guidewire allows the T-tube to be replaced by a percutaneous catheter, thus avoiding the occurrence of bile leakage, biloma or choleperitoneum.

The rest of the strategies mentioned are technical innovations that, to our knowledge, have not yet been published. Some, such as modified port placement, have more to do with greater ease than improved outcomes, and others are strategies for very rare cases, which makes their utility difficult to assess. The aim this document is simply to introduce and describe them, so it would be desirable for future publications to validate or contradict them.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Canullán C, Baglietto N, Merchán del Hierro P, Petracchi E. Diez estrategias para mejorar la eficacia de la cirugía biliar laparoscópica. Cir Esp. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ciresp.2020.05.027