Numerous studies have shown a high prevalence of cardiovascular disease in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The aim of this study was to analyse the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidity in a Canary Islands population diagnosed with COPD, and compared it with data from the general population.

Patients and methodsA cross-sectional study was carried out in 300 patients with COPD and 524 subjects without respiratory disease (control group). The two groups were compared using standard bivariate methods. Logistic regression models were used to estimate the cardiovascular risks in COPD patients compared to control group.

ResultsPatients with COPD showed a high prevalence of hypertension (72%), dyslipidaemia (73%), obesity (41%), diabetes type 2 (39%), and sleep apnoea syndrome (30%) from mild stages of the disease (GOLD 2009). There was a 22% prevalence of cardiac arrhythmia, 16% of ischaemic heart disease, 16% heart failure, 12% peripheral vascular disease, and 8% cerebrovascular disease. Compared to the control group, patients with COPD had a higher risk of dyslipidaemia (OR 3.24, 95% CI; 2.21–4.75), diabetes type 2 (OR 1.52, 95% CI; 1.01–2.28), and ischaemic heart disease (OR 2.34, 95% CI; 1.22–4.49). In the case of dyslipidaemia, an increased risk was obtained when adjusted for age, gender, and consumption of tobacco (OR 5.04, 95% CI; 2.36–10.74).

ConclusionsPatients with COPD resident in the Canary Islands have a high prevalence of hypertension, dyslipidaemia, ischaemic heart disease, and cardiac arrhythmia. Compared to general population, patients with COPD have a significant increase in the risk of dyslipidaemia.

Múltiples estudios han revelado una alta prevalencia de patología cardiovascular en pacientes con enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica (EPOC). El objetivo de este estudio ha sido analizar la prevalencia de factores de riesgo y comorbilidad cardiovascular en una muestra de pacientes canarios diagnosticados de EPOC y compararla con datos procedentes de la población general de Canarias.

Pacientes y métodosEstudio trasversal en 300 pacientes con EPOC y en 524 sujetos del grupo control sin patología respiratoria. Los pacientes fueron seleccionados según criterios de inclusión de las consultas ambulatorias de Neumología, mientras que los grupos control procedían de la población general adulta. Se registró información referente a: edad, sexo, hábito tabáquico, pruebas de función pulmonar y comorbilidad cardiovascular. Se compararon mediante análisis bivariado las dos muestras en cuanto al riesgo cardiovascular y, mediante modelos de regresión logística, se estimaron los riesgos en relación con la morbilidad cardiovascular de los pacientes con EPOC sobre la del grupo control.

ResultadosLos pacientes con EPOC presentaron una elevada prevalencia de hipertensión arterial (72%), dislipidemia (73%), obesidad (41%), diabetes tipo 2 (39%) y síndrome apnea-hipopnea del sueño (30%) desde estadios leves de la enfermedad (GOLD 2009). La prevalencia de arritmia cardíaca fue del 22%, la de cardiopatía isquémica del 16%, la de insuficiencia cardíaca del 16%, la de enfermedad vascular periférica del 12% y la de enfermedad cerebrovascular del 8%. Respecto al grupo control, los pacientes con EPOC presentaban un mayor riesgo de tener dislipidemia (OR 3,24; IC del 95%: 2,21–4,75), diabetes tipo 2 (OR 1,52; IC del 95%: 1,01–2,28) y cardiopatía isquémica (OR 2,34; IC del 95%: 1,22–4,49). En el caso de la dislipidemia, se obtuvo un incremento del riesgo cuando se ajustó por edad, sexo y consumo de tabaco acumulado (OR 5,04; IC del 95%:2,36–10,74).

ConclusionesLos pacientes con EPOC residentes en Canarias tienen una alta prevalencia de hipertensión arterial, dislipidemia, cardiopatía isquémica y arritmia cardíaca. Frente a población general, los pacientes con EPOC presentan un importante incremento en el riesgo de presentar dislipidemia.

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is one of the main causes of mortality in the developed world.1,2 Several epidemiological case–control studies have shown that patients with COPD present with a greater number of classic cardiovascular risk factors such as obesity, type 2 diabetes (T2D), arterial hypertension (HTN) or metabolic syndrome.3–15 This gives rise to a high rate of cardiovascular death in these patients, especially those with less severe forms of COPD.16–18 In terms of the Spanish population, the CONSISTE study reports a greater prevalence of these factors in patients with COPD than in the general population, as well as a significantly higher incidence of ischaemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease and peripheral vascular disease.19

Furthermore, recent data from a cohort of the general population revealed that the population of the Canary Islands has an unfavourable cardiovascular risk profile, with the highest rates of obesity, T2D, dyslipidaemia and HTN in Spain in the active population under the age of 65.20–23 Given this context, it would be of interest to ascertain the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with COPD residing on the Canary Islands; an aspect that has never been investigated to date. The primary objective of this study was to analyse the prevalence of risk factors and cardiovascular disease in a sample of patients diagnosed with COPD on the Canary Islands, both globally and by severity of the disease according to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2009 guidelines, with grading defined by the GOLD 2011 guidelines. The study's secondary objective was to compare morbidity in these patients with the morbidity of a sample of the general Canary Island population.

Patients and methodsAn observational, cross-sectional study of a cohort of patients with COPD (n=300) and a sample of adults with no respiratory disease (n=524) from the “CDC de Canarias” (Canary Islands cardiovascular, diabetes and cancer) cohort.20 The 300 patients were enrolled from Pulmonology outpatient clinics of the Tenerife Health Area, specifically the south and metropolitan regions, from January 2012 to December 2015. They had all been previously diagnosed with COPD (codes ICD-10: J44-J44.9) and met the following inclusion criteria: aged over 40; active smoker or former smoker of more than 10 pack-years; forced expiratory volume in 1s (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio less than 70% after the administration of salbutamol, previous follow-up by a pulmonologist of at least 6 months; and the ability to understand the study and complete the necessary procedures. The exclusion criterion comprised the presence of any chronic respiratory disease other than COPD. Patients were consecutively enrolled in the study by participating pulmonology specialists in the order in which they were seen. No other screening criteria were applied, with the exception of the inclusion and exclusion criteria detailed above. The following patient information was collected from their electronic medical records (EMR) and from a face-to-face interview with their pulmonologist: age; gender; smoking habits (smoker or former smoker), including smoking intensity measured by pack-years; weight (kg); height (m); associated cardiovascular risk factors, such as HTN, T2D, dyslipidaemia, sleep apnoea–hypopnoea syndrome (SAHS) and obesity; cardiovascular disease such as arrhythmia, ischaemic heart disease, congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular accident, peripheral arterial disease and chronic kidney disease; dyspnoea determined by the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) scale; number of exacerbations in the last year; and Charlson comorbidity index. The results of the pulmonary function tests were also recorded and the patients were stratified in accordance with the four stages of severity specified in the GOLD 2009 guidelines and according to the GOLD 2011 grading system. Patients from all protocols underwent prior follow-up of at least 6 months, so all the study-related data were collected from the medical records of the participating centres, although they were only confirmed when the patient was enrolled in the study. COPD diagnosis had to be confirmed by pulmonary function tests in order to classify the disease. Risk factors and/or comorbidity were diagnosed based on the notes of each of the participating doctors that were recorded in the EMR.

The sample from the “CDC de Canarias” cohort (n=524) was selected based on the following inclusion criteria: aged over 40 and no COPD or any other respiratory disease. This cohort was recruited from the year 2000 to 2005 from the general adult population of the Canary Islands. In short, each patient was subjected to an anthropometric examination and blood pressure monitoring, a blood test that included lipid and glucose profile, and a comprehensive questionnaire that covered any family or personal history of cardiovascular risk factors. All this information can be viewed at: http://www.cdcdecanarias.org/. They were all inhabitants of Tenerife or the other provincial islands and were registered at the Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria (HUNSC), which is the referral hospital for COPD patients used in the study.

This study was submitted to and approved by HUNSC's Bioethics Committee prior to its commencement.

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis of all the study variables was performed. The qualitative variables were expressed as percentages and 95% CI, while the quantitative variables were expressed as means±standard deviations. The Student's t test was used to compare means, or an ANOVA to compare two or more groups. The chi-square test was used to compare proportions. Logistic regression models were used to estimate patient risk versus the control group, where the dependent variable was each of the cardiovascular risk variables; models were initially adjusted for age and gender, and then for age, gender and pack-years in the final models. The analyses were performed with the SPSS v2.0 statistical software, and differences with a p-value <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant in all cases.

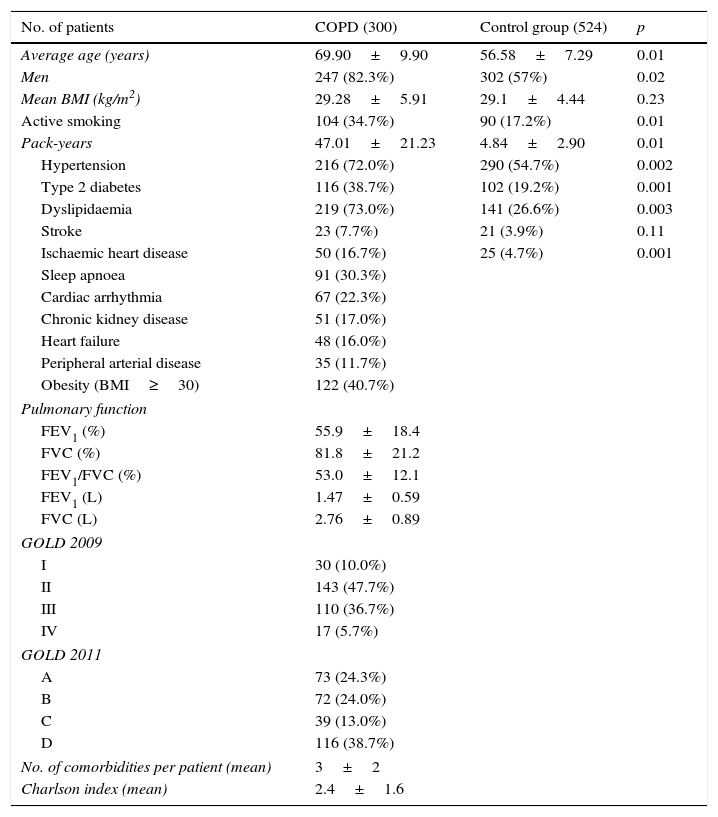

ResultsThree hundred patients with COPD were enrolled, together with 524 subjects with no respiratory disease in the control group. The characteristics of the COPD patients are detailed in Table 1. They were mostly men, with a mean age of almost 70 and a high prevalence of obesity, and more than one third of our sample were active smokers. According to the four stages of severity specified in the GOLD 2009 guidelines, 30 patients (10%) were classified as GOLD I, 143 (47.7%) GOLD II, 110 (36.7%) GOLD III and 17 (5.7%) GOLD IV. According to the GOLD 2011 grading system, 73 (24.3%) were graded as GOLD A, 72 (24%) GOLD B, 39 (13%) GOLD C and 116 (38.7%) GOLD D.

Cardiovascular risk profile characteristics of COPD patients and the control group.

| No. of patients | COPD (300) | Control group (524) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average age (years) | 69.90±9.90 | 56.58±7.29 | 0.01 |

| Men | 247 (82.3%) | 302 (57%) | 0.02 |

| Mean BMI (kg/m2) | 29.28±5.91 | 29.1±4.44 | 0.23 |

| Active smoking | 104 (34.7%) | 90 (17.2%) | 0.01 |

| Pack-years | 47.01±21.23 | 4.84±2.90 | 0.01 |

| Hypertension | 216 (72.0%) | 290 (54.7%) | 0.002 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 116 (38.7%) | 102 (19.2%) | 0.001 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 219 (73.0%) | 141 (26.6%) | 0.003 |

| Stroke | 23 (7.7%) | 21 (3.9%) | 0.11 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 50 (16.7%) | 25 (4.7%) | 0.001 |

| Sleep apnoea | 91 (30.3%) | ||

| Cardiac arrhythmia | 67 (22.3%) | ||

| Chronic kidney disease | 51 (17.0%) | ||

| Heart failure | 48 (16.0%) | ||

| Peripheral arterial disease | 35 (11.7%) | ||

| Obesity (BMI≥30) | 122 (40.7%) | ||

| Pulmonary function | |||

| FEV1 (%) | 55.9±18.4 | ||

| FVC (%) | 81.8±21.2 | ||

| FEV1/FVC (%) | 53.0±12.1 | ||

| FEV1 (L) | 1.47±0.59 | ||

| FVC (L) | 2.76±0.89 | ||

| GOLD 2009 | |||

| I | 30 (10.0%) | ||

| II | 143 (47.7%) | ||

| III | 110 (36.7%) | ||

| IV | 17 (5.7%) | ||

| GOLD 2011 | |||

| A | 73 (24.3%) | ||

| B | 72 (24.0%) | ||

| C | 39 (13.0%) | ||

| D | 116 (38.7%) | ||

| No. of comorbidities per patient (mean) | 3±2 | ||

| Charlson index (mean) | 2.4±1.6 | ||

Values expressed as number of patients (percentage) or mean±standard deviation.

BMI, body mass index; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1s; FVC, forced vital capacity; GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; No., number.

In terms of cardiovascular profile, our COPD patients had a high incidence of dyslipidaemia, HTN, T2D and SAHS, while in terms of cardiovascular disease, a high prevalence of ischaemic heart disease, cardiac arrhythmia and heart failure was found. The mean number of cardiovascular comorbidities per patient was 3±2 (Table 1).

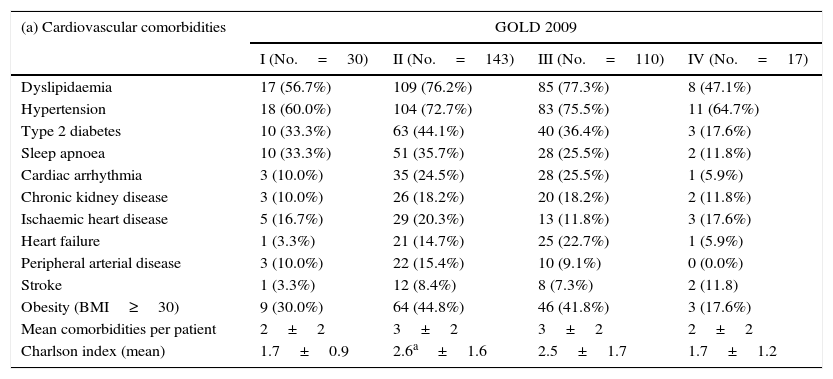

Having stratified the patients by disease severity according to the GOLD 2009 guidelines, no significant differences were found between the four groups in terms of cardiovascular risk factors (Table 2a). Conversely, having stratified by 2011 GOLD grades, HTN and SAHS were found to be more prevalent in GOLD grade B and D patients (Table 2b). In terms of cardiovascular disease, no significant differences were found between the different GOLD 2009 stages (Table 2a). However, the difference between the GOLD 2011 grade B and D groups (Table 2b) was significant, with patients also presenting significantly more comorbidities.

Prevalence of cardiovascular comorbidity in COPD patients according to the GOLD 2009 guidelines (a) and the GOLD 2011 guidelines (b).

| (a) Cardiovascular comorbidities | GOLD 2009 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I (No.=30) | II (No.=143) | III (No.=110) | IV (No.=17) | |

| Dyslipidaemia | 17 (56.7%) | 109 (76.2%) | 85 (77.3%) | 8 (47.1%) |

| Hypertension | 18 (60.0%) | 104 (72.7%) | 83 (75.5%) | 11 (64.7%) |

| Type 2 diabetes | 10 (33.3%) | 63 (44.1%) | 40 (36.4%) | 3 (17.6%) |

| Sleep apnoea | 10 (33.3%) | 51 (35.7%) | 28 (25.5%) | 2 (11.8%) |

| Cardiac arrhythmia | 3 (10.0%) | 35 (24.5%) | 28 (25.5%) | 1 (5.9%) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 3 (10.0%) | 26 (18.2%) | 20 (18.2%) | 2 (11.8%) |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 5 (16.7%) | 29 (20.3%) | 13 (11.8%) | 3 (17.6%) |

| Heart failure | 1 (3.3%) | 21 (14.7%) | 25 (22.7%) | 1 (5.9%) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 3 (10.0%) | 22 (15.4%) | 10 (9.1%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Stroke | 1 (3.3%) | 12 (8.4%) | 8 (7.3%) | 2 (11.8) |

| Obesity (BMI≥30) | 9 (30.0%) | 64 (44.8%) | 46 (41.8%) | 3 (17.6%) |

| Mean comorbidities per patient | 2±2 | 3±2 | 3±2 | 2±2 |

| Charlson index (mean) | 1.7±0.9 | 2.6a±1.6 | 2.5±1.7 | 1.7±1.2 |

| (b) Cardiovascular comorbidities | GOLD 2011 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (No.=73) | B (No.=72) | C (No.=39) | D (No.=116) | |

| Dyslipidaemia | 46 (63.0%) | 58 (80.6%) | 30 (76.9%) | 85 (73.3%) |

| Hypertension | 41 (56.2%) | 60 (83.3%)b | 26 (66.7%) | 89 (76.7%)b |

| Type 2 diabetes | 23 (31.5%) | 36 (50.0%) | 14 (35.9%) | 43 (37.1%) |

| Sleep apnoea | 27 (37.0%) | 29 (40.3%)c | 6 (15.4%) | 29 (25.0%) |

| Cardiac arrhythmia | 7 (9.6%) | 23 (31.9%)b | 6 (15.4%) | 31 (26.7%)b |

| Chronic kidney disease | 6 (8.2%) | 18 (25.0%)b | 4 (10.3%) | 23 (19.8%) |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 5 (6.8%) | 23 (31.9%)b,c | 1 (2.6%) | 21 (18.1%) |

| Heart failure | 6 (8.2%) | 12 (16.7%) | 3 (7.7%) | 27(23.3%)b |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 4 (5.5%) | 17 (23.6%)b | 2 (5.1%) | 12 (10.3%) |

| Stroke | 2 (2.7%) | 6 (8.3%) | 1 (2.6%) | 14 (12.1%) |

| Obesity (BMI≥30) | 29 (39.7%) | 38 (52.8%) | 15 (38.5%) | 40 (34.5%) |

| Mean comorbidities per patient | 2±2 | 4±2b,c | 2±2 | 3±2b |

| Charlson index (mean) | 1.9±1.3 | 2.8±1.5b,c | 1.8±1.2 | 2.6±1.8b,c |

Values expressed as number of patients (percentage).

BMI, body mass index; No., number.

The comparative analysis between the COPD group and the control group (Table 1) found the proportion of male patients and the average age to be higher in the COPD group. HTN, T2D, dyslipidaemia and ischaemic heart disease were also significantly more prevalent in COPD patients. However, no differences in obesity or cerebrovascular accidents were identified.

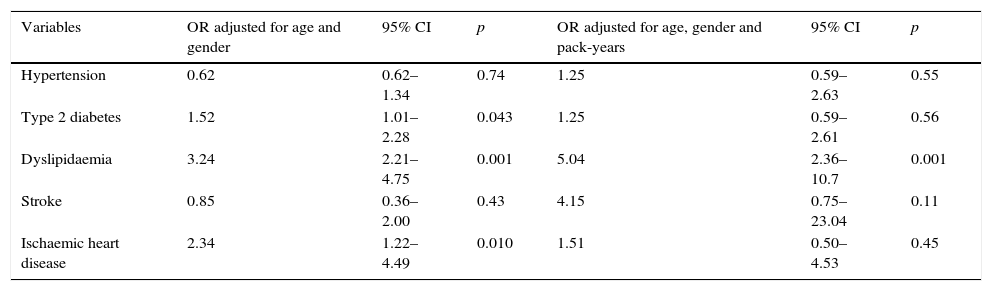

The estimated risk of onset of cardiovascular disease in COPD patients versus the control group and the analysed risk factors are shown in Table 3. After adjusting for gender and age, the logistic regression model found that patients with COPD were three times more likely to develop dyslipidaemia (OR 3.24; 95% CI: 2.21–4.75), twice as likely to develop ischaemic heart disease (OR 2.34; 95% CI: 1.22–4.49) and had a 50% greater chance of suffering from T2D (OR 1.52; 95% CI: 1.01–2.28) versus the Canary Islands’ general population. No differences in the risk of onset of HTN or cerebrovascular accident were found. When the models were also adjusted for pack-years, the risk of patients developing dyslipidaemia versus the control group increased (OR 5.04; 95% CI: 2.36–10.74), while the findings for the other variables were not significant.

Logistic regression models to estimate the risk of onset of cardiovascular disease in COPD patients versus the control group.

| Variables | OR adjusted for age and gender | 95% CI | p | OR adjusted for age, gender and pack-years | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | 0.62 | 0.62–1.34 | 0.74 | 1.25 | 0.59–2.63 | 0.55 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 1.52 | 1.01–2.28 | 0.043 | 1.25 | 0.59–2.61 | 0.56 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 3.24 | 2.21–4.75 | 0.001 | 5.04 | 2.36–10.7 | 0.001 |

| Stroke | 0.85 | 0.36–2.00 | 0.43 | 4.15 | 0.75–23.04 | 0.11 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 2.34 | 1.22–4.49 | 0.010 | 1.51 | 0.50–4.53 | 0.45 |

To estimate risks (OR), being a patient with COPD was taken as a risk category versus the reference (control group).

PYI, pack-years index.

Our results found a high prevalence of cardiovascular disease among COPD patients residing in any of the provinces of the Canary Islands, including from the earliest stages of the disease. Risk of dyslipidaemia among COPD patients was found to be five times higher compared to the island group's general population.

The prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors is higher in our sample than in other similar studies conducted in Europe, the USA and Latin America, particularly HTN, dyslipidaemia and obesity.24–27 Concerning the North American population in particular, Barr et al.24 found that 57% of patients with COPD were hypertensive, 49% had dyslipidaemia and 26% were diabetic, all of which are below the findings in our population. In comparison with other studies conducted in Spain, the prevalence of HTN, dyslipidaemia and obesity was found to be higher in our sample than in the CONSISTE study, which reported figures of 51.8%, 48.3% and 35.2%, respectively.19 However, the prevalence of T2D in our cohort was not greater than that found in patients on mainland Spain.

The high prevalence of cardiovascular disease in COPD patients is noteworthy.9,10,19,28,29 In our study, the high rate of cardiac arrhythmia and ischaemic heart disease is particularly striking, including in the mild stages of the disease. These results are consistent with the latest epidemiological evidence, which highlights the role of systemic inflammation in the pathogenesis of arteriosclerosis, especially in patients with COPD,30–33 in whom increased CRP, fibrinogen or oxidised LDL levels have been reported in stable conditions. Furthermore, the Charlson comorbidity index values were 2.6±1.6 in stage II of the GOLD 2009 guidelines, which are similar to those reported in the ECCO study (2.7±2.0), in which the COPD population presented with greater airflow obstruction (stage III of the GOLD 2009 guidelines).34 All of the above paints a bleak clinical picture for COPD patients and a shorter life expectancy, including from the earliest stages of the disease.

In addition, epidemiological studies conducted on the Canary Islands have shown that the archipelago's population is overfed and has a high rate of physical inactivity, giving rise to obesity20 and a predicted increase in the risk of developing SAHS. Soler et al. recently established that up to 65% of COPD patients with moderate–severe airflow obstruction had an apnoea–hypopnoea index-greater than 5.35 The prevalence identified in our sample is likely to be underestimated owing to those subjects without excessive daytime sleepiness, in whom a lack of treatment could give rise to cardiovascular disease.36 Furthermore, the prevalence of cerebrovascular disease and peripheral arterial disease were slightly lower than that reported in COPD patients on the Spanish mainland.19

Of course, the high cardiovascular morbidity found in patients with COPD could simply be a reflection of that reported for the general population of the Canary Islands. Upon comparison of the patient group versus the general population from which the patient group derives, it can be seen that the prevalence of cardiovascular disease and risk factors is higher in the COPD group, although this could be explained by the higher proportion of male patients and the higher average age in the patient group. However, having adjusted the multivariate models for age and gender, this high risk was maintained in the COPD patients versus the control group. This increased risk was particularly striking for dyslipidaemia, which rose even further after adjusting for tobacco consumption. This may be explained by the fact that more of the COPD patients were smokers and therefore consumed more tobacco. In any case, this finding may indicate that smoking plays a fundamental role in the atherogenic profile in COPD patients regardless of whether or not there is an underlying proinflammatory state that could give rise to lipid fraction abnormalities. In this sense, several studies have shown that patients with COPD have elevated triglyceride and HDL levels compared to the control population, although their involvement in the onset of cardiovascular events in these patients is still open to debate.33,37

This study does have several limitations. The first concerns the small and localised sample studied. Obviously, a larger sample would have revealed significant differences that were not possible to identify in our study. In addition, patients were recruited from the outpatient clinics of a single hospital, and it would be interesting to recruit a larger sample from across the islands that is representative of all COPD patients residing on the archipelago. Secondly, the subjects selected for the control group did not undergo forced spirometry. Although it could lead to information bias, which should be assessed with caution, given the low smoking prevalence, coupled with very little tobacco exposure assessed by pack-years in the control group, it can be reasonably assumed that these people did not have COPD, as ascertained in the health interview. Furthermore, the COPD patient group and the control group were not established simultaneously, which could account for some variation in the prevalences found. We would expect these prevalences in the control group to be higher if measured today. Even so, we believe that the dyslipidaemia difference detected between COPD patients and the control group would be maintained, albeit somewhat less pronounced. Further information bias may have arisen as the variables were taken from the patients’ medical records, although the current standardisation of diagnostic criteria should have minimised any differences in criteria applied by the studies consulted. Finally, it must be noted that it was not possible to obtain all the information necessary from the control group to calculate the Charlson comorbidity index as many of the variables required were not recorded in the database of the “CDC de Canarias” cohort. As a result, this index could not be compared between the groups.

That said, one of the strengths of our study concerns the COPD severity stages, where it was found that the mildest forms of the disease (GOLD 2009 stages I and II) accounted for 57% of the sample, which obviously includes patients that may have been treated in primary care and in whom detected cardiovascular comorbidity is even more relevant. It is also important to mention that this is the first study on COPD patients of the Canary Islands to evaluate the prevalence of cardiovascular comorbidity. The lipid and atherogenic profile of these patients should be further studied with a view to establishing even clearer correlations between this disease and associated increased cardiovascular risk.

In conclusion, our data show that COPD patients residing in the Canary Islands have a high prevalence of cardiovascular disease, including in the earliest stages of the condition. These patients should be closely monitored for the onset of coronary events and cardiac arrhythmia, which would increase the complexity of their care.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related directly or indirectly to the content of this article.

Please cite this article as: Figueira Gonçalves JM, Dorta Sánchez R, Rodríguez Pérez MC, Viña Manrique P, Díaz Pérez D, Guzmán Saenz C, et al. Comorbilidad cardiovascular en pacientes con enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica en Canarias (estudio CCECAN). Clin Invest Arterioscler. 2017;29:149–156.