The cardiovascular prevention strategy by autonomous communities can be variable since the competences in health are transferred. The objective of the study was to determine the degree of dyslipidaemia control and the lipid-lowering pharmacological therapy used in patients at high/very high cardiovascular risk (CVR) by autonomous communities.

MethodsObservational, cross-sectional, descriptive study based on a consensus methodology. Information on the clinical practice of 145 health areas belonging to 17 Spanish autonomous communities was collected through face-to-face meetings and questionnaires administered to the 435 participating physicians. Furthermore, aggregate non-identifiable data were compiled from 10 consecutive dyslipidaemic patients that each participant had recently visited.

ResultsOf the 4,010 patients collected, 649 (16%) had high and 2,458 (61%) very high CVR. The distribution of the 3,107 high/very high CVR patients was balanced across regions, but there were inter-regional differences (P < 0.0001) in the achievement of target LDL-C<70 and <55 mg/dL, respectively. High-intensity statins in monotherapy or in combination with ezetimibe and/or PCSK9 inhibitors were used in 44, 21 and 4% of high CVR patients, while in those at very high CVR it rose to 38, 45 and 6%, respectively. The use of these lipid-lowering therapies at national level was significantly different between regions (P = 0.0079).

ConclusionsEven though the distribution of patients at high/very high CVR was similar between autonomous communities, inter-territorial differences were identified in the degree of achievement of LDL cholesterol therapeutic goal and use of lipid-lowering therapy.

La estrategia de prevención cardiovascular en las comunidades autónomas (CCAA) puede ser variable, al estar transferidas las competencias en sanidad. El objetivo del estudio fue conocer el control de la dislipemia y terapia hipolipemiante utilizada en pacientes de alto/muy alto riesgo cardiovascular (RCV) por CCAA.

MétodosEstudio descriptivo, transversal, multicéntrico no aleatorizado basado en una metodología de consenso. Se recogió información de práctica clínica en 145 áreas sanitarias de 17 CCAA españolas mediante reuniones presenciales y cuestionarios realizados a los 435 médicos participantes. Se recopilaron datos agregados no identificables de 10 pacientes dislipémicos consecutivos que cada participante hubiera visitado recientemente.

ResultadosDe los 4.010 pacientes compilados, 649 (16%) eran de alto y 2.458 (61%) de muy alto RCV. La distribución de los 3.107 pacientes de alto/muy alto RCV fue equilibrada entre regiones, pero hubo diferencias interterritoriales (P < 0,0001) en la consecución del objetivo de cLDL<70 e <55 mg/dL, respectivamente. Las estatinas de alta intensidad en monoterapia o combinadas con ezetimiba y/o inhibidores PCSK9 se utilizaron en el 44, 21 y 4% de los pacientes de alto RCV, mientras que en los de muy alto RCV era del 38, 45 y 6%, respectivamente. El uso de estas terapias hipolipemiantes a nivel nacional fue significativamente diferente entre regiones (P = 0,0079).

ConclusionesA pesar de que la distribución de los pacientes de alto/muy alto RCV fue similar entre CCAA, se identificaron diferencias interterritoriales en el grado de consecución del objetivo terapéutico en cLDL y de utilización de la terapia hipolipemiante.

Diseases of the circulatory system remain the leading cause of death according to data from the Spanish National Institute of Statistics (INE) in 2020,1 at 119,853 deaths, which represents 24.3% of all deaths. Despite the multifactorial origin of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and the large number of risk factors described, the INTERHEART study2 showed that nine modifiable factors account for 90% of the population attributable risk in men and 94% in women. Dyslipidaemia, specifically, as assessed by the apolipoprotein (Apo) B/Apo A1 ratio, was responsible for 54% of the attributable risk of myocardial infarction. In Spain, the ZACARIS study3 found that obesity, smoking, and hypercholesterolaemia were, in that order, the factors with the greatest population impact on ischaemic heart disease, independently of sex, age, and other risk factors.

Despite strong scientific evidence supporting the causal role of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol4,5 in atherogenesis, international6,7 and national8,9 multicentre clinical practice studies repeatedly indicate that dyslipidaemic patients, especially those at high/very high cardiovascular risk (CVR), are undertreated and, therefore, the success rate in achieving therapeutic targets in LDL cholesterol is unacceptably low. The causes of poor control are diverse and affect the different strata involved in health care, namely the administration, health professionals, and patients.

Differences in access to and use of healthcare systems, together with the health status of the population, make place of residence one of the essential determinants of health.10,11 In Spain, healthcare competences are devolved to the autonomous communities (ACs), and therefore strategies for effective cardiovascular prevention can be variable and heterogeneous. In this regard, a national study outlining the care map for dyslipidaemic patients showed that most of the differences were geographical in nature, and that there is some discrepancy in the use of a shared protocol between care levels.12 However, it is not known whether there are regional differences in cholesterolaemia control in Spain and specifically in patients with high/very high CVR.

The Observatorio del Manejo del Paciente Dislipémico (Observatory for the Management of the Dyslipaedimic Patient),13 a project led by the Spanish Society of Cardiology (SEC) and the Spanish Society of Arteriosclerosis (SEA), has provided insight into actual healthcare practice in the control of dyslipidaemia, and uses as a reference the lipid targets recommended by the 2019 European guidelines.14 Drawing from this experience, the aim of the present study was to determine the different healthcare situations by autonomous community based on the rate of achievement of the therapeutic targets for LDL cholesterol in patients at high/very high CVR and the cholesterol-lowering pharmacological strategy used.

MethodsSpain’s Observatorio del Manejo del Paciente Dislipémico is a descriptive, cross-sectional, multicentre, non-randomised study, whose design, selection of participants, healthcare areas, and analysis materials have been described previously.13 In short, information was collected on clinical practice in 145 health areas, representing 86% of the national health areas, belonging to 17 AC in Spain, by means of multidisciplinary face-to-face meetings and questionnaires to participating physicians (3 per health area). Of the 435 physicians who participated in the interviews, 125 (28.7%) were specialists in family and community medicine, 142 (32.6%) in cardiology, 103 (23.7%) in internal medicine, 61 (14%) in endocrinology, 3 (.7%) in nephrology, and 1 (.2%) in neurology. In addition, aggregate data were collected from 10 consecutive dyslipidaemic patients that each participant had recently visited: type of patient (primary/secondary prevention), relevant comorbidities, CVR profile, lipid-lowering treatment received (therapeutic group), and LDL-cholesterol range achieved. All information collected was based on the experience and perception of the different participating physicians, of whom 401 (92.2%) submitted valid questionnaires. Approval by the relevant ethics committee or the patient's signed informed consent were not required because no individual patient or medical history data were recorded.

Statistical analysisQuantitative data were analysed descriptively including mean, standard deviation (SD), median, and interquartile range, maximum and minimum, for continuous variables; and n (%) for categorical variables. The results were disaggregated by autonomous community. The chi-squared test (χ2) was used to compare the percentage of attainment of therapeutic targets for LDL cholesterol and the use of lipid-lowering drug therapy between the ACs. A p-value of < .05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS statistical package (version 19.0, Chicago, IL, USA).

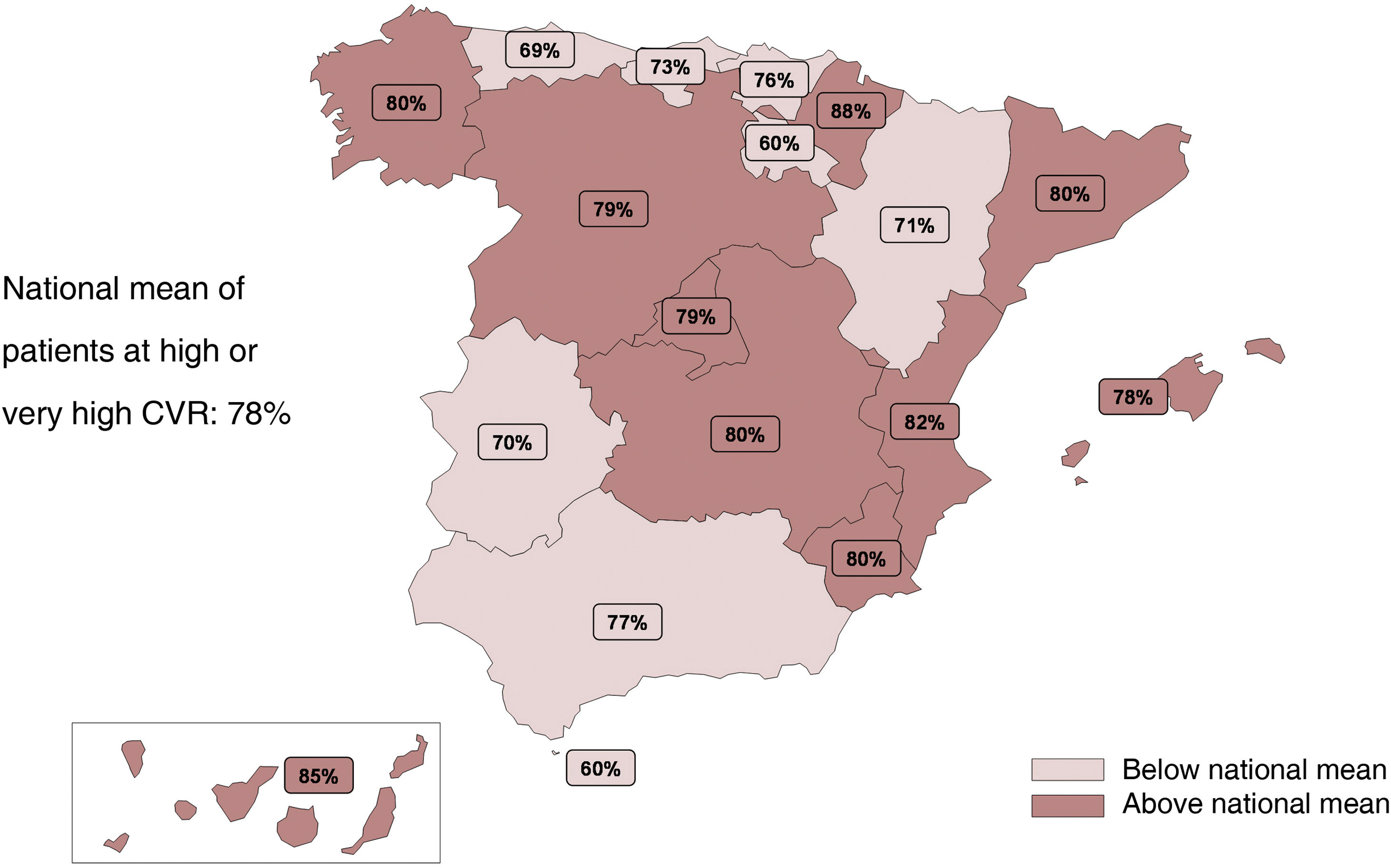

ResultsThe representativeness of the multidisciplinary meetings by AC was proportional to that of the general population over the total Spanish population. The 401 physicians who submitted valid questionnaires provided a sample of 4,010 patients with aggregated data from actual clinical practice. Of the 4,010 patients, 649 (16%) were at high and 2,458 (61%) were at very high CVR. Eighty-nine per cent of the very high CVR patients were in secondary prevention. In addition, 14% of the high/very high CVR patients had familial hypercholesterolaemia, 56% diabetes mellitus, and 27% chronic kidney disease. The distribution of the 3,107 high/very high CVR patients was balanced across the regions, ranging from 88% in Navarra to 60% in La Rioja and Ceuta (Fig. 1).

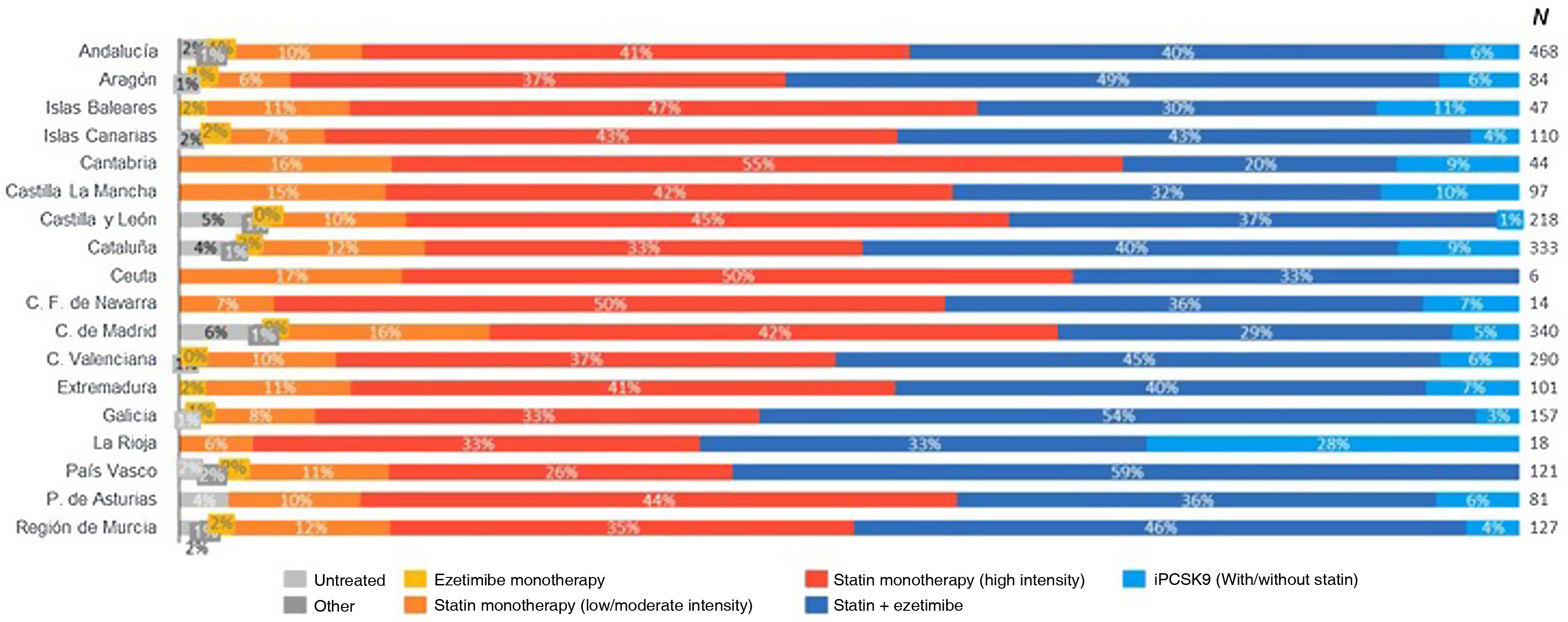

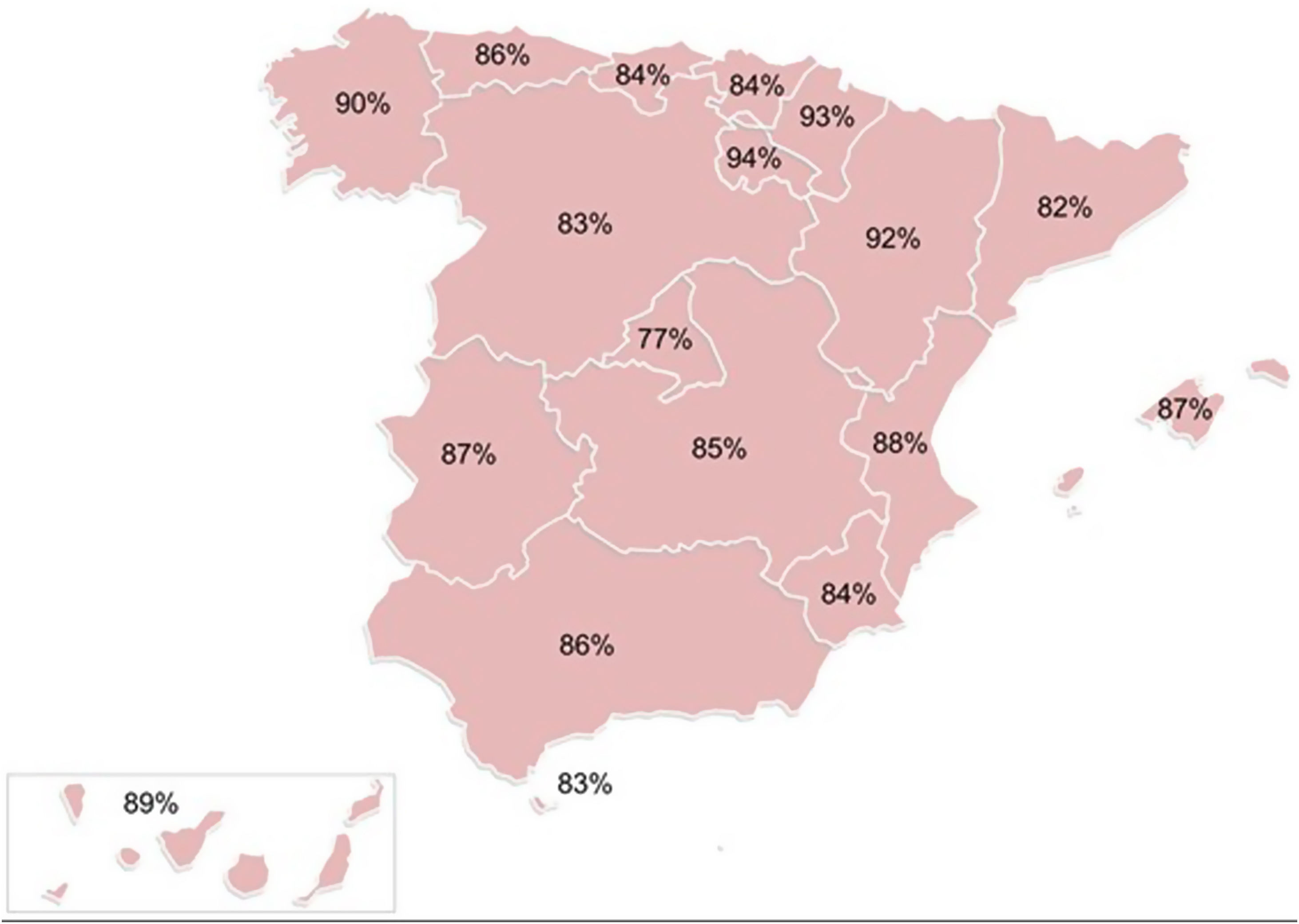

It should be noted that in the patients with high CVR the most commonly used therapeutic strategies were, in decreasing order, high-intensity statin monotherapy (44%), followed by low/moderate intensity statins (21%), and statin plus ezetimibe combination therapy (21%); in contrast, in the patients at very high CVR, statin plus ezetimibe combination therapy was the most commonly used treatment (45%), followed by high-intensity statin monotherapy (38%). Specifically, high-intensity statin monotherapy was used by up to 55% in Cantabria and statins with ezetimibe by up to 59% in the Basque Country. It would be fair to mention at this point that in patients at high/very high CVR, low/moderate intensity statins in monotherapy are still used in more than 15% in different ACs, such as Cantabria, Castilla-La Mancha, Madrid, or Ceuta (Fig. 2). When analysing at national level, the use of high-intensity statin treatment in monotherapy or statins in combination with ezetimibe and/or a proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitor, statistically significant differences were found between regions (p = .0079), ranging from 94% in La Rioja to 77% in the Community of Madrid (Fig. 3).

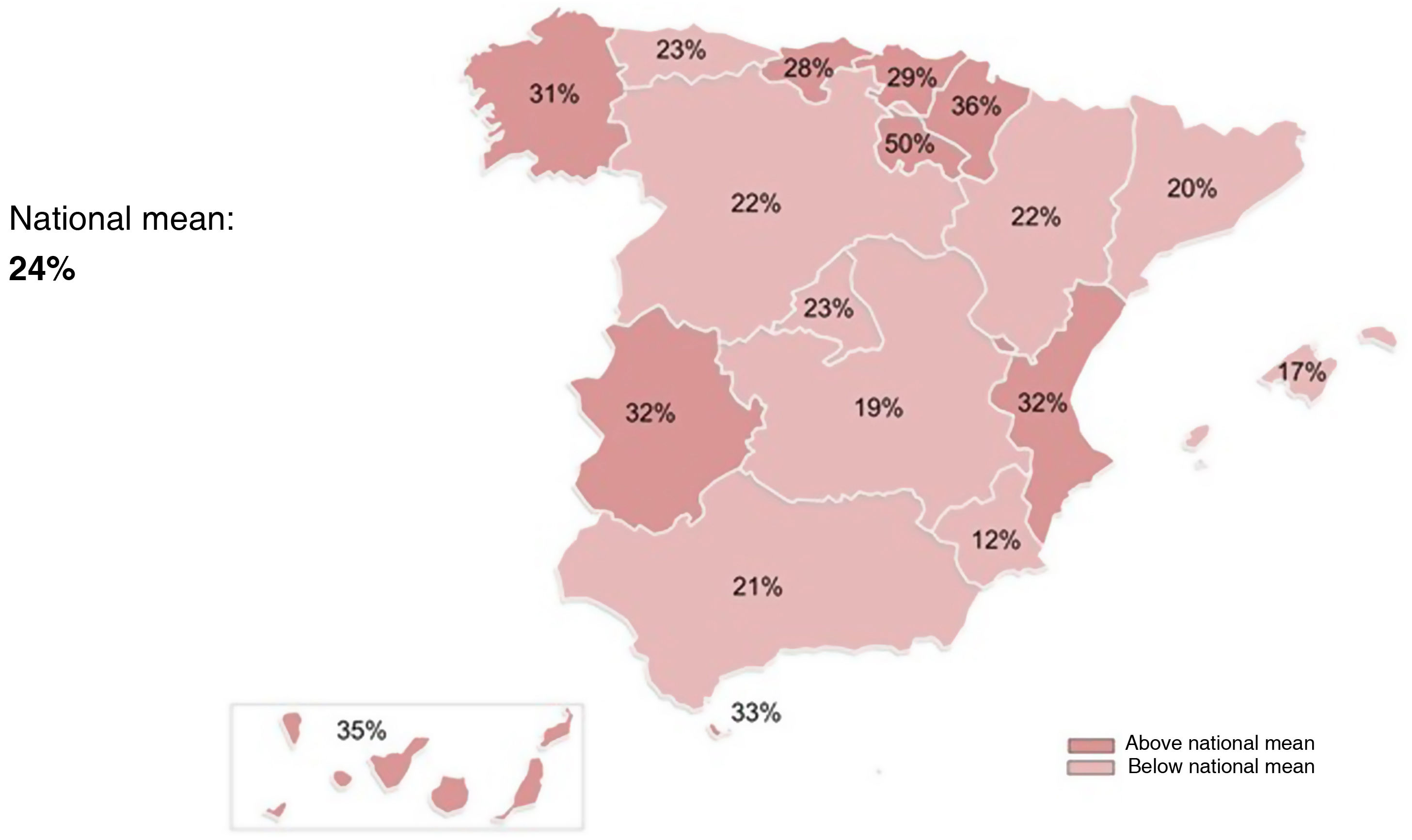

Of the high CVR patients, only 22% achieved the therapeutic target of LDL cholesterol <70 mg/dl, and of the very high CVR patients, 25% achieved LDL cholesterol <55 mg/dl. If we group the patients at high/very high CVR who achieved the therapeutic target, it is worth noting firstly that there are differences between regions (p < .0001), fluctuating between 50% in La Rioja and 12% in the Region of Murcia (Fig. 4). Secondly, the use of statin plus ezetimibe and/or a PCSK9 inhibitor combination therapy had a decisive impact on the achievement of LDL-cholesterol targets in patients at high and at very high CVR, achieving success rates of 52% and 69%, respectively.

Distribution of patients at high/very high cardiovascular risk achieving the therapeutic target for LDL-cholesterol according to the ESC/EAS 2019 guidelines14 by autonomous community.

The present study highlights the disparity in the control of hypercholesterolaemia in patients at high/very high CVR between the different Spanish autonomous regions, resulting from the use of different pharmacological strategies to reduce LDL cholesterol.

The most commonly used pharmacological regimen in patients at high CVR was high-intensity statin monotherapy, and in those at very high CVR, statin plus ezetimibe combination therapy. In this regard, it is worth noting that the usage rate of the statin plus ezetimibe combination was 45% in patients at very high CVR, which is significantly higher than that reported in other studies.6,7 However, in different regions, such as Cantabria, Castilla-La Mancha, Community of Madrid, and Ceuta, more than 15% of patients at high/very high CVR continue to receive low/moderate intensity statins in monotherapy. Although these data show a clear improvement with respect to previous studies,6–9 we should not forget that this lipid-lowering regimen in patients at high/very high CVR usually implies undertreatment, as it is unlikely to lead to a reduction of LDL cholesterol of at least 50%.

Of note in the present study are the differences between ACs (p = .0079) in the use of high-intensity statin therapy in monotherapy or statins in combination with ezetimibe and/or a PCSK9 inhibitor. Despite the underutilisation of PCSK9 inhibitors (5% and 6% of high and very high CVR patients, respectively), their use with/without statin and/or ezetimibe achieved a therapeutic target achievement rate in very high CVR patients of 69%. A recent national survey of PCSK9 inhibitor requirements revealed important differences between ACs due to barriers to PCSK9 inhibitor prescribing by regional regulatory agencies and hospital pharmacy commissions. In general, the use of PCSK9 inhibitors was more widespread in hospitals and in the autonomous communities with SEA lipid units.15

Nationally, 22% of patients at high and 25% of those at very high CVR achieved the therapeutic targets for LDL cholesterol according to the 2019 European guidelines14 data which, while clear opportunity for improvement, are higher than those reported in the DA VINCI7 and, recently, REALITY16 studies. Variations ranged from 50% of patients at high/very high CVR controlled in La Rioja to 12% in the Murcia region. Overall, these data confirm the poor rate of achievement of therapeutic targets for LDL cholesterol, which is partly attributable to the underuse of currently available lipid-lowering drugs. These regional differences could be related to the different presence of physicians from specialised units (cardiac rehabilitation or lipid units) in the participating groups as a determinant of optimal use of lipid-lowering drug treatment, although this study was not designed for that purpose. In this context, we consider it appropriate to advocate a conceptual change in cardiovascular prevention by emphasising, based on the results of new regression studies with PCSK9 inhibitors using innovative intravascular imaging techniques,17 that in patients with cardiovascular disease the achievement of recommended or lower LDL cholesterol levels is accompanied by a reduction in atherosclerotic burden and beneficial effects on plaque composition, therefore we can claim that we are providing aetiological treatment of the disease.

The present study is not without limitations. Thus, due to the non-randomised nature of the study, quantitative patient parameters to assess the achievement of LDL-cholesterol targets were collected in a range of levels. Moreover, the participating physicians had a special clinical interest in the management of dyslipidaemia and CVR, and very many belonged to cardiac rehabilitation units of the SEC or lipid and CVR units of the SEA. Therefore, it is possible that the actual clinical practice outcomes are even worse than those described.

ConclusionAchieving lipid control targets is the cornerstone of effective cardiovascular prevention, but we are far from achieving this goal. Although the distribution of patients at high/very high CVR was similar between the autonomous regions, differences between regions were identified in the control of dyslipidaemia and in the use of lipid-lowering drug therapy. These data highlight the inequalities that exist in Spanish territory, highlighting the need for actions to cover unmet needs, improve dyslipidaemia control, and achieve therapeutic targets in LDL cholesterol, especially in those communities with a suboptimal degree of control.

FundingThe present paper is a study of the Research Agency of the Spanish Society of Cardiology and the Spanish Society of Arteriosclerosis, sponsored by an unconditional grant from Daiichi Sankyo Spain.

Conflict of interestsJuan Cosin-Sales has received lecture fees from Almirall, Amgen, Daiichi Sankyo, Ferrer, MSD, Novartis, Organon, Rovi and Sanofi; has participated in consultancies for Almirall, Amgen, MSD, and Sanofi; and has received research grants from Amgen, Ferrer, MSD, and Sanofi.

Raquel Campuzano has received lecture fees from Amgen, Daiichi Sankyo, Ferrer, Mylan, MSD, Organon, Sanofi, Servier and Novartis; has participated in consultancies from Novartis, Amgen, Sanofi, and Servier; and has received scientific or research project collaborations from Amgen, Daiichi Sankyo, Ferrer, Organon, Servier and Novartis.

José Luis Díaz has received fees for lectures, consultancies, and scientific collaborations from Amgen, Bayer, Boëringher, BMS, Lilly, MSD, Mylan, Novartis, Novo-Nordisk, Pfizer, Rovi, Rubió, Sanofi, Daiichi Sankyo, and Servier.

Carlos Escobar has received lecture/consulting fees from Almirall, Amgen, Daiichi Sankyo, Esteve, Ferrer, MSD, Novartis, Organon, Rovi, Sanofi, Servier, and Viatris.

María Rosa Fernández has received lecture fees from Amgen, Sanofi, Ferrer, Daiichi Sankyo, Organon and Rovi; she has participated in consultancies for Novartis, Amgen, Sanofi, and Amarin.

Juan José Gómez-Doblas has received lecture fees from Amgen, Sanofi, Daiichi Sankyo, Organon, and MSD; has participated in consultancies for Amgen, Sanofi, and Amarin; and has received scientific and research project collaborations from Amgen, Sanofi, Ferrer, and Daiichi Sankyo.

José María Mostaza has participated in consultancies and/or conferences, and has undertaken projects for Pfizer, Amarin, Ferrer, Sanofi, Amgen, Alter, Servier, Novartis, and Daiichi Sankyo.

Juan Pedro-Botet has received lecture fees from Amarin, Amgen, Daiichi Sankyo, Esteve, MSD, Sanofi, and Viatris; and has participated in consultancies for Amarin, Amgen, Daiichi Sankyo, Esteve, Ferrer, Sanofi, and Viatris.

Núria Plana has received lecture fees from Amgen, Sanofi, Daiichi Sankyo Mylan, and Alexion.

Pedro Valdivielso has received lecture fees from Amgen, Sanofi, Ferrer, Amarin, Akcea, Sobi, MSD, Novartis, Viatris, PTC therapeutics, and Daiichi Sankyo; has participated in consultancies from Daiichi Sankyo, Amgen, Sanofi, Akcea, Alexion, and Amarin; and has received research grants from Ferrer, Akcea, and Sobi.

We would like to thank all the participants in the Dyslipidaemia Observatory for the information provided to identify potential areas for improvement in the management of dyslipidaemic patients in each care area. IQVIA supported the development of the study in conducting and moderating the sessions.