GALIPEMIAS is a study designed to establish the prevalence of familial dyslipidemia in the general population of Galicia. The objective of the present study was to assess the prevalence of atherogenic dyslipidemia (AD), its relationship with other cardiovascular risk (CVR) factors, and the degree of lipid control.

MethodsCross-sectional study carried out in the general population over 18 years of age residing in Galicia and with a health card from the Galician Health Service (N = 1000). Selection of the sample by means of random sampling by conglomerates. The AD prevalence adjusted for age and sex and the related variables were analyzed.

ResultsThe prevalence of AD adjusted for age and sex was 6.6% (95% CI: 5.0%–8.3%). Arterial hypertension, altered basal glycemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease were more frequent in subjects with AD than in the rest of the population. 47.5% of the subjects with AD had a high or very high CVR. Lipid-lowering drugs were received by 38.9% (30.5% statins) of the participants with AD (46.1% of those with high and 71.4% of those with very high CVR). 25.4% of the subjects with AD had target LDL-C levels, all of them with low or moderate CVR.

ConclusionsThe prevalence of AD in the general adult population of Galicia is not negligible, and it was related to several CVR factors and cardiovascular disease. Despite this, this lipid alteration was underdiagnosed and undertreated.

GALIPEMIAS es un estudio diseñado para establecer la prevalencia de las dislipemias familiares en la población general de Galicia. El objetivo del presente estudio fue determinar la prevalencia de dislipemia aterogénica (DA), su relación con otros factores de riesgo de riesgo cardiovascular (RCV) y el grado de control lipídico.

MétodosEstudio transversal realizado en población general mayor de 18 años de edad residente en Galicia y con tarjeta sanitaria del Servicio Gallego de Salud (N = 1.000). Selección de la muestra mediante muestreo aleatorio por conglomerados. Se analizó la prevalencia de DA ajustada por edad y sexo y, las variables relacionadas.

ResultadosLa prevalencia de DA ajustada por edad y sexo fue de un 6,6% (IC 95%: 5,0%–8,3%). La hipertensión arterial, glucemia basal alterada, diabetes mellitus tipo 2 y enfermedad cardiovascular aterosclerótica fueron más frecuentes en individuos con DA que en el resto de la población. El 47,5% de los sujetos con DA presentaba un RCV alto o muy alto. Recibían fármacos hipolipemiantes el 38,9% (30,5% estatinas) de los participantes con DA (46,1% de los de alto y el 71,4% de los de muy alto RCV). El 25,4% de los sujetos con DA presentaban niveles de cLDL en objetivo, siendo todos ellos de bajo o moderado RCV.

ConclusionesLa prevalencia de dislipemia aterogénica en población general adulta de Galicia no es despreciable, se relacionó con varios factores de RCV y la enfermedad cardiovascular aterosclerótica. A pesar de ello, estuvo infradiagnosticada e infratratada.

Atherogenic dyslipidaemia (AD), characterised by the coexistence of increased plasma triglyceride (TG) levels and decreased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), reflects an imbalance between TG-rich lipoproteins containing apolipoprotein B100 (Apo B-100) and anti-atherogenic lipoproteins containing apolipoprotein AI (Apo AI). In this dyslipidaemia, although low-density lipoprotein (LDL-C) cholesterol concentrations are in the normal range or slightly elevated, there is a predominance of small dense LDL particles or phenotype B of Austin et al.1,2 Its pathogenesis underlies insulin resistance and is therefore common in obesity, metabolic syndrome,3 type 2 diabetes mellitus4 or polycystic ovary syndrome.5

Epidemiological studies have shown an increased risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ACVD) in individuals with AD,6 and this risk is considered to be 2–3 times higher than in the general population.7 Based on post hoc analysis of different clinical studies.8–13 AD is considered to be responsible for the residual lipid-mediated cardiovascular risk (CVR) in patients treated with statins and controlled LDL-C.14

In the EURIKA study, the prevalence of AD in the European population over 50 years of age without ACVD was 9.9%.15 In Spain, its prevalence in the working population is 5.7%, 7%16 11.1% in the hypertensive population,17 13.1% in subjects treated with statins,18 17.9% in patients seen in lipid units19 and 27.1% in those with moderate to high CVR seen in primary care.20 Recently, the SIMETAP study conducted in the autonomous community of Madrid found an age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of AD of 13.1%.21 However, its prevalence and relationship with ACVD in the general population is unknown.

Differences in access to and use of health systems, together with the health status of the population, contribute to the fact that place of residence is one of the essential determinants of health.22,23 In this sense, GALIPEMIAS was designed to establish the prevalence of familial dyslipidaemia, ACVD and the degree of lipid control in the general population of Galicia. The aim of the present study was to determine the prevalence of AD, its relationship with other CVR and ACVD risk factors, as well as the extent of lipid control.

Material and methodsGALIPEMIAS is a cross-sectional study conducted in the general population residing in Galicia, aged ≥ 18 years and with a Galician Health Service (SERGAS) health card. Subjects with advanced neurodegenerative processes (unable to attend a consultation), institutionalised in geriatric centres and those living outside Galicia during the study period were excluded.

A sample size of 1000 participants was calculated based on an estimated joint prevalence of the main familial dyslipidaemias (familial combined hyperlipidaemia, familial hypertriglyceridaemia and familial hypercholesterolaemia) of around 3.5% and a design effect of 1.7% due to the type of sampling, with a 95% confidence interval (CI). We sampled by clusters (basic health areas) which were assigned a sample size proportional to their population size. Finally, due to feasibility criteria, 70 municipalities belonging to the 8 basic health areas were selected, which included a population of 1.4 million inhabitants (61.3% of the resident population in Galicia), 99% of which were SERGAS beneficiaries.

The methodology of the study has been described previously.24 Briefly, the fieldwork was carried out in 3 phases. In the first stage, trained staff contacted 1507 SERGAS users by telephone (4717 random calls were required) to finally obtain a sample of 1003 users who met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate, after a detailed explanation of the study. In a second phase, 13 medical researchers from SERGAS (7 internists, 4 family and community medicine doctors and 2 endocrinologists), trained for the study in 2 previous sessions, reviewed the electronic medical records of all participants - IANUS online platform - to collect epidemiological, clinical, analytical and therapy data. In the absence of a complete lipid profile analysis not older than 6 months, the participant was sent a leaflet by post to complete at their health centre. In this phase, participants with dyslipidaemia were selected, and were considered as such those who presented in the last analysis a concentration of total cholesterol (TC) ≥ 240 mg/dl or TG ≥ 150 mg/dl or HDL-C < 50 mg/dl (women) or <40 mg/dl (men) or LDL-C ≥ 160 mg/dl, as well as those currently treated with lipid-lowering drugs.

In a final phase, dyslipidaemic participants were assessed in person for family history, detailed physical examination and new laboratory tests. All study processes were carried out between December 2012 and January 2015. The analytical parameters included in this study correspond to those collected in the second phase and those from the physical examination to the third phase.

AD was defined by the joint presence of hypertriglyceridaemia, defined as a TG ≥ 150 150 mg/dl concentration and an HDL-C deficit, defined as an HDL-C concentration < 50 mg/dl in women or <40 mg/dl in men. For the stratification of CVR and lipid control targets (LDL-C), the recommendations of the 2019 European guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias25 and the consensus document of the Atherogenic Dyslipidaemia Group of the Spanish Society of Arteriosclerosis26 were followed.

Statistical analysisContinuous variables with normal distribution are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD); otherwise, they are presented as median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables are shown as absolute and relative frequencies. For comparison of quantitative variables between groups, Student's t-test or Mann-Whitney U test was used depending on whether the variable followed a normal distribution or not. The Chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables between the same groups. A rate adjustment by the direct method was performed to calculate the age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of AD taking as reference the population of Galicia in 2012 stratified into 4 age groups (<30, 30–59, 60–69 and ≥70 years). A bilateral level of statistical significance was considered with a value of P < .05. SPSS® version 18 for Windows (SPSS Inc.; Chicago, IL, USA) and EPIDAT version 4.2 were used for database and statistical analysis.

The study was promoted by SERGAS, classified by the Spanish Agency for Medicines and Health Products (AEMPS) as a Non-Post-Authorisation Observational Study (Non-EPA) and approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Galicia.

ResultsOf the 1003 subjects who met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate, 35 were excluded because they did not have a recent blood test and refused a new one, and another 35 because of loss of contact. This resulted in a sample of 933 participants, 925 of whom had complete data for analysis.

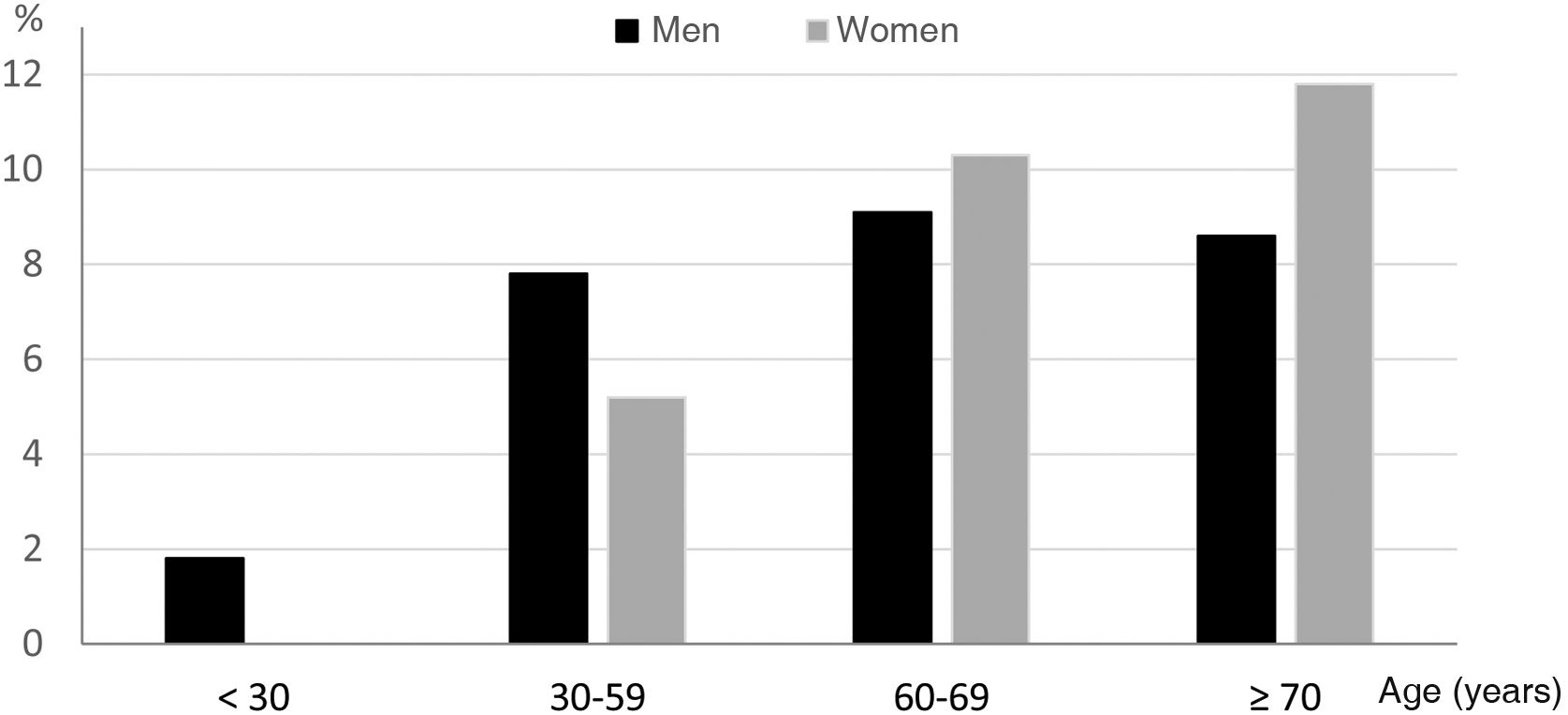

A total of 59 participants met criteria for AD. The age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of AD was 6.6% (95% CI 5.0–8.3), higher in men (7.3%; 95% CI 4.7–11.1) than in women (6.4%; 95% CI 3.4–10.3), although not for all age groups as shown in Fig. 1. It should be noted that no cases of AD were observed in women younger than 30 years and that from the age of 70 years onwards AD was more prevalent in women.

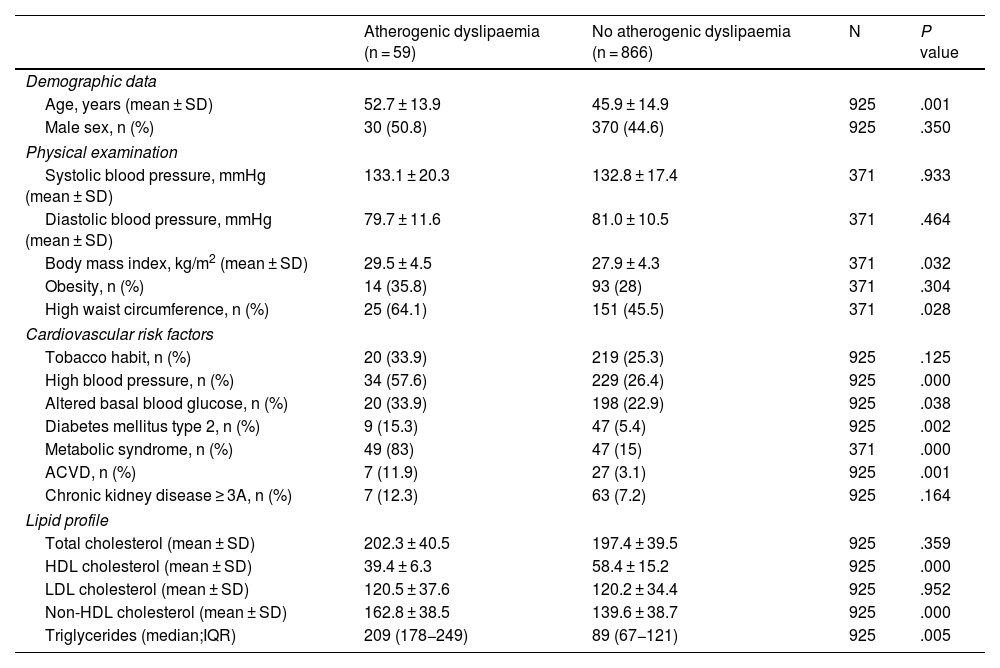

The clinical characteristics of the subjects, according to the presence or absence of AD are shown in Table 1. It should be noted that body mass index, prevalence of hypertension, altered basal glycaemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus and CVD were higher in individuals with AD compared to those without AD. The prevalence of ACVD was twice as high in individuals with AD as in the overall study population.

Main clinical characteristics of the GALIPEMIAS study subjects.

| Atherogenic dyslipaemia (n = 59) | No atherogenic dyslipaemia (n = 866) | N | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | ||||

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 52.7 ± 13.9 | 45.9 ± 14.9 | 925 | .001 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 30 (50.8) | 370 (44.6) | 925 | .350 |

| Physical examination | ||||

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg (mean ± SD) | 133.1 ± 20.3 | 132.8 ± 17.4 | 371 | .933 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg (mean ± SD) | 79.7 ± 11.6 | 81.0 ± 10.5 | 371 | .464 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 (mean ± SD) | 29.5 ± 4.5 | 27.9 ± 4.3 | 371 | .032 |

| Obesity, n (%) | 14 (35.8) | 93 (28) | 371 | .304 |

| High waist circumference, n (%) | 25 (64.1) | 151 (45.5) | 371 | .028 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | ||||

| Tobacco habit, n (%) | 20 (33.9) | 219 (25.3) | 925 | .125 |

| High blood pressure, n (%) | 34 (57.6) | 229 (26.4) | 925 | .000 |

| Altered basal blood glucose, n (%) | 20 (33.9) | 198 (22.9) | 925 | .038 |

| Diabetes mellitus type 2, n (%) | 9 (15.3) | 47 (5.4) | 925 | .002 |

| Metabolic syndrome, n (%) | 49 (83) | 47 (15) | 371 | .000 |

| ACVD, n (%) | 7 (11.9) | 27 (3.1) | 925 | .001 |

| Chronic kidney disease ≥ 3A, n (%) | 7 (12.3) | 63 (7.2) | 925 | .164 |

| Lipid profile | ||||

| Total cholesterol (mean ± SD) | 202.3 ± 40.5 | 197.4 ± 39.5 | 925 | .359 |

| HDL cholesterol (mean ± SD) | 39.4 ± 6.3 | 58.4 ± 15.2 | 925 | .000 |

| LDL cholesterol (mean ± SD) | 120.5 ± 37.6 | 120.2 ± 34.4 | 925 | .952 |

| Non-HDL cholesterol (mean ± SD) | 162.8 ± 38.5 | 139.6 ± 38.7 | 925 | .000 |

| Triglycerides (median;IQR) | 209 (178−249) | 89 (67−121) | 925 | .005 |

ACVD, Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; HDL, High-density lipoprotein; IQR, Interquartile range; LDL, Low-density lipoprotein; SD, Standard deviation.

Subjects with AD showed low, moderate, high and very high CVR in 39%, 13.5%, 23.7% and 23.7%, respectively. When the electronic medical records of the study participants were reviewed, none of the subjects with AD had the presence of this condition reflected in the clinical document.

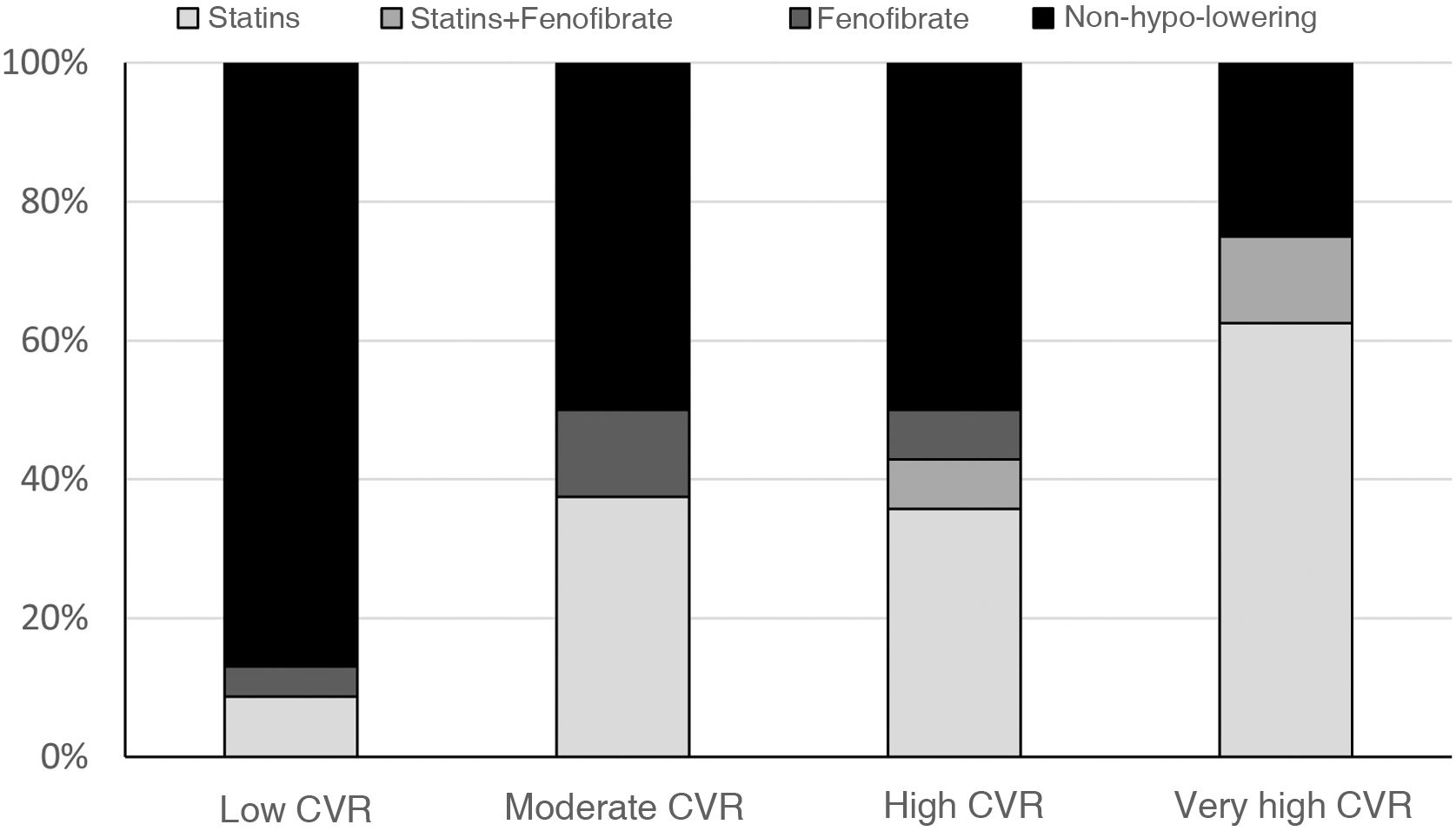

At the time of the study, 38.9% of the participants with AD were receiving lipid-lowering drug treatment, with 13% in those with low CVR, 50% in those with moderate CVR, 46.1% in those with high CVR and 71.4% in those with very high CVR (Fig. 2). Of all subjects with AD, 30.5% were being treated with statins (1/3 of them with high-intensity statins), 5% with combination therapy (statin-fenofibrate) and 3.4% with fenofibrate monotherapy. None of them received treatment with ezetimib.

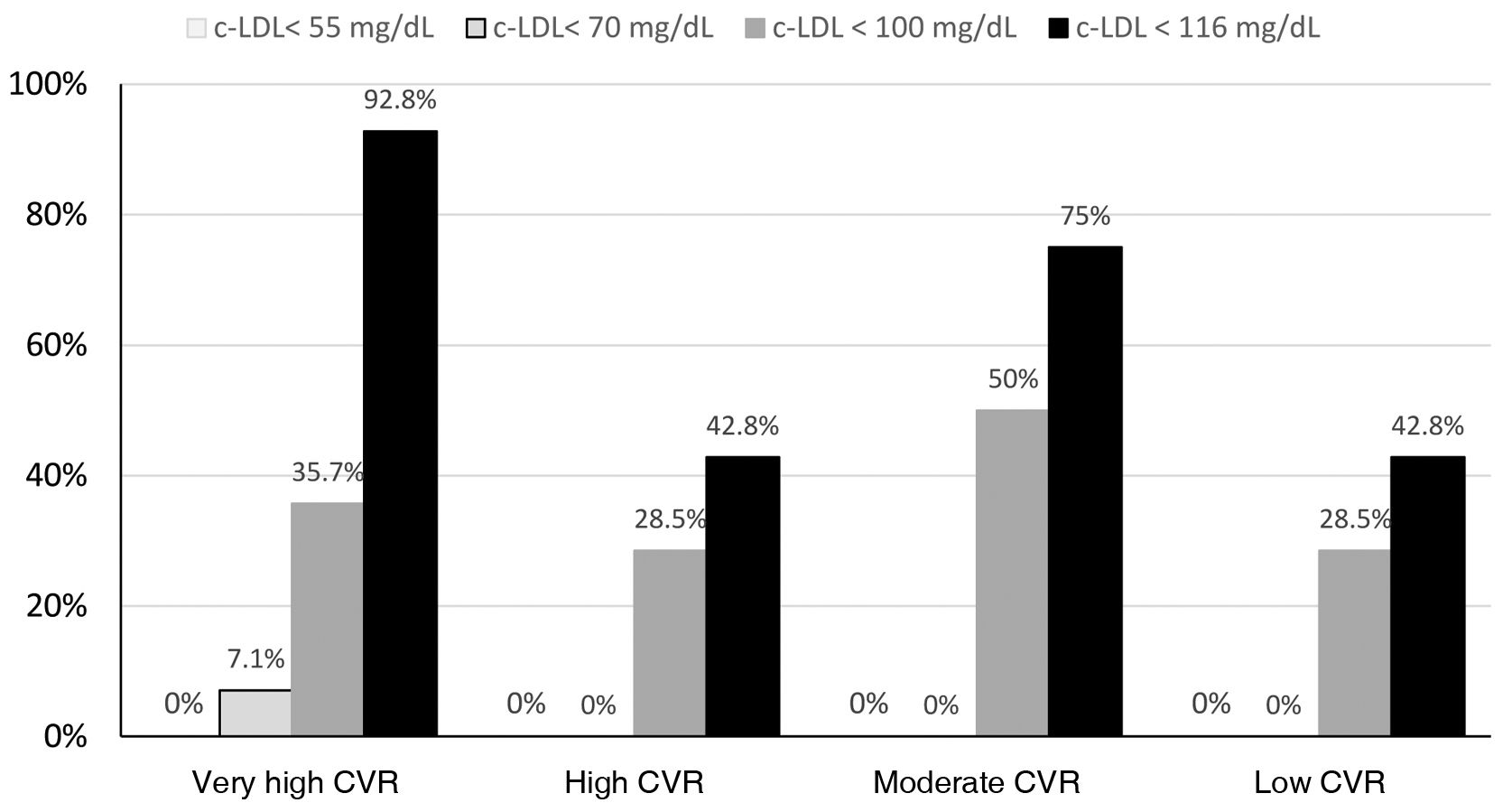

Twenty-five point four per cent (n = 15) of subjects with AD had LDL-C levels on target according to the 2019 European guidelines, all of them being of low or moderate CVR. 47.8% of participants with AD and low CVR and 50% with moderate CVR had LDL-C levels on target, with 18.1% and 75% being treated with statins, respectively. None of the subjects with AD and high or very high CVR had reached the 2019 European guidedline LDL-C targets (Fig. 3), or the non-HDL-cholesterol targets.

DiscussionIn the present analysis of the GALIPEMIAS study, carried out in the general adult population living in Galicia, a prevalence of subjects with AD of 6.6% was observed. These individuals had more CVRFs and more CVD, with almost half of them having a high or very high CVR, despite which barely 40% received lipid-lowering treatment and only one in four had LDL-C concentrations at therapeutic target.

In this study, we observed a lower prevalence of AD compared to the SIMETAP-DA study (13.1% vs. 6.6%). The different design of the two studies may partly explain these differences. Thus, while in SIMETAP-DA21 the population was randomly sampled from a population >18 years of age assigned to 121 family doctors from the health service of the Community of Madrid interested in participating in the project and the population without information on biochemical variables was excluded, in the GALIPEMIAS study, randomised sampling was carried out in the Galician population over 18 years of age benefiting from SERGAS (99% of the population), including subjects without initial information on biochemical variables, but who agreed to undergo a blood extraction test to obtain them. The impact of the different distribution of factors associated with AD between the two populations, which could be explained by hereditary or social factors, cannot be ignored.

AD is not a lipid disorder that is difficult to identify, although none of the subjects in our study had previously been identified. This highlights its frequent under-diagnosis,27 although 87.6% of the professionals reported that they routinely assessed AD in their clinical practice.28 It is possible that the prioritisation of the therapeutic target of LDL-C in cardiovascular prevention, especially in subjects with high and very high CVR, has led to a certain lack of confidence in the role of AD as a vascular risk factor. Moreover, as of 2019, intervention studies with drugs that reduce plasma TG concentrations, such as extended-release niacin with laropiprant29,30 and fibrates31,32 have not shown cardiovascular benefits when administered alongside conventional medical therapy, including statins. The only evidence comes from post hoc analyses of patients with AD or one of its components treated with fibrates.33–36 This may have undoubtedly contributed to the low recognition of this dyslipidaemia in clinical practice.

The GALIPEMIAS study found a higher prevalence of CVRF and ACVD in individuals with AD, results in line with other studies in other populations.15–21 Despite this, less than half of the individuals with AD were categorised as having a high or very high CVR. This fact should lead us to reflect on the possible underestimation of CVR with the tools used to calculate it in subjects with AD.27 In this regard, it should be noted that the new SCORE-2 and SCORE-OP CVR calculation tables use non-HDL cholesterol, which includes all atherogenic lipoprotein cholesterol.37

Overall, only one in four patients with AD achieved the therapeutic LDL-C targets. It is therefore not surprising that only 35.5% of the subjects with AD were prescribed a statin. It is also striking that none of the 28 subjects with AD and high or very high CVR showed target LDL-C levels, considering that LDL-C concentrations in AD are characteristically normal or slightly elevated. The explanation is twofold: 40% were not being treated with statins and the rest were not receiving high-intensity statins.

The main limitation of our study is that informed consent was obtained by telephone, which could have influenced a low participation rate and which we tried to mitigate with different strategies. In any case, this circumstance would fundamentally influence its external validity. On the other hand, it is worth mentioning the lack of data on LDL particle size, which is only measured for research purposes, and on serum Apo-100 concentration, which is not available in all health care laboratories.

ConclusionsSome 6.6% of the adult population residing in Galicia has AD. This population had not been previously identified and AD was associated with several CVR factors and twice the prevalence of CVD compared to the general population, four times higher compared to subjects without AD. None of the subjects with AD and high or very high CVR had LDL-C within therapeutic targets. Overall, the majority of cases either did not receive lipid-lowering drug treatment or received insufficient treatment.

FundingThis study was partially funded by a grant from AstraZeneca, who was not involved in the study design, data analyses or the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.