Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia. To assess the need for anticoagulation is essential for its management. Our objective was to investigate whether the indication of anticoagulation was adequate in patients diagnosed with non-valvular AF, given the CHA2-DS2-VASc scale, measuring the International Normalized Ratio range (INR) in patients treated with anti-vitamin K drugs.

MethodsThis is an observational and cross sectional study. 232 patients with atrial fibrillation were included. We analysed demographic, the CHA2-DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED variables, the treatment and INR values for 6 consecutive months. The confrontation of variables was performed using chi-square and Mantel-Haenzel test.

ResultsThe prevalence of AF was 1.05%. The 88.4% had CHA2-DS2-VASc ≥2. The 71.1% were taking anticoagulants, of which 58.2% were under antivitamin K. The 46.7% of patients taking antivitamin K, presented inadequate range of INR. There was a greater prescription of antivitamin K in patients with persistent or permanent AF compared to the paroxysmal form (62.8 vs. 37.2% p<0.001). The use of drugs that increase bleeding was associated with a worse control of INR after adjustment for the main variables of clinical relevance (odds ratio 2.17 [1.02–4.59], p=0.043).

ConclusionsThe level of anticoagulation with antivitamin K was inadequate in our sample, despite a proper follow up and adherence to treatment. Patients with paroxysmal AF received less antivitamin K than those with persistent/permanent AF.

La fibrilación auricular (FA) es la arritmia cardiaca más frecuente. En su manejo, es clave valorar la necesidad de anticoagulación. Nuestro objetivo fue valorar en pacientes diagnosticados de FA no valvular si la indicación de anticoagulación es adecuada en función de la escala CHA2DS2-VASc y la adecuación del rango del International Normalizad Ratio (INR) en los pacientes en tratamiento con antivitamina K.

MétodosEstudio observacional, analítico transversal. Se seleccionaron 232 pacientes con diagnóstico de FA no valvular. Se han analizado variables demográficas, variables de la escala CHA2DS2-VASc, tratamiento prescrito y valores de INR durante 6 meses consecutivos. La comparación de variables se realizó con ji cuadrado y la tendencia lineal entre grupos por Mantel Haenzel, siendo calculadas las odds ratios.

ResultadosLa prevalencia total de FA no valvular en el área fue 1,05%. El 88,4% presentó un CHA2DS2-VASc ≥ 2. Un 71,1% de pacientes con fibrilación auricular estaban anticoagulados, de los que el 58,2% tomaban fármacos antivitamina K. El 46,7% de los pacientes en tratamiento con acenocumarol presentó un INR con un tiempo en rango terapéutico directo insuficiente. La prescripción de antivitamina K en los pacientes con FA permanente fue superior que en pacientes con FA paroxística (62,8 vs. 37,2%, p<0,001). El consumo de fármacos que aumentan el sangrado se asoció a un peor control de INR (tras ajuste por las principales variables de relevancia clínica (odds ratio 2,17 [1,02-4,59], p=0,043).

ConclusionesEl control de la anticoagulación oral con antivitamina K fue subóptimo pese a la adecuada adherencia de los pacientes. Los pacientes con FA paroxística recibieron menos antivitamina-K que los de FA persistente/permanente.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia. It affects 1–2% of the population1,2 and 8.5% of the Spanish population over the age of 60.3 It is characterised by chaotic (disorganised and rapid) electrical activity within the atria, which causes a decreased blood flow rate to certain parts of the atria, mainly the left atrial appendage, which promotes coagulation and intra-atrial thrombus formation. Its association with thromboembolic events, therefore, is clear.4 Moreover, the natural course of the disease5,6 results in atrial remodelling, perpetuating AF over time.7

Numerous independent risk factors for the development of AF have been identified,8 with the most characteristic being age and hypertension in population-based samples.9 In addition, AF not only has a higher risk of mortality compared to patients in sinus rhythm,9 but also a higher risk of thromboembolic events,10–13 with the most common being cardioembolic stroke, which has the highest rate of recurrence and a lower survival rate.14,15 The risk of stroke and other thromboembolic episodes is not homogeneous and depends on certain clinical conditions that have been grouped into different risk stratification models. Of these models, the CHA2DS2-VASc scoring system is the most appropriate for identifying non-valvular AF patients with a truly low risk of stroke (CHA2DS2-VASc=0), recommended in anticoagulation guidelines,16–19 and also for identifying patients with a high risk of stroke and thromboembolic complications (CHA2DS2-VASc ≥2).19

However, the HAS-BLED scoring system is recommended for estimating risk of bleeding, with a score of ≥3 indicating exhaustive correction of reversible risk factors for bleeding, and for performing regular, closer follow-up of these patients.3

Despite the importance of assessing the risk of thromboembolism in patients with AF, very few primary care studies have been conducted in relation to this risk3,10,19–21 and the level of anticoagulation control required based on the International Normalised Ratio (INR).

Therefore, the objectives of this study were: to assess whether patients with non-valvular AF are correctly classified according to the CHA2DS2-VASc scoring system and anticoagulated based on this classification; to assess the anticoagulant prescribed; and, in those patients prescribed a vitamin K antagonist, to assess the effectiveness of this treatment using the INR and adherence to the required blood testing schedule. If the patient's INR was not within the therapeutic range, it was also necessary to assess associated variables.

Material/patients and methodStudy populationThe study's reference population included all individuals receiving care within a basic health area with 21,700 users.

Study design and participantsThis was an observational and analytical cross-sectional study. The sample selection period was between February and May 2016. In order to study the effectiveness of vitamin K antagonist therapy using serial INR measurements and adherence to this therapy and check-ups, INR values for each patient for the 6 months prior to inclusion were studied, i.e. from August–November 2015 until the patient's date of inclusion.

All users, of both genders, from the pre-determined area who met the following criteria were selected: 14 years of age and over and with a record of a non-valvular AF episode in their electronic medical records, logged in both the Primary Care software (OMI-AP) and the hospital's medical record software (Selene). Patients with valvular AF, defined as AF related to rheumatic valvular disease or prosthetic heart valves, were excluded from the analysis.

Variables and measurementsPrimary variable: adaptation of indications for oral anticoagulant therapy according to the thromboembolic risk and measured using the CHA2DS2-VASc scoring system, with DOAC therapy considered appropriate for patients with non-valvular AF and CHA2DS2-VASc ≥2.

Socio-demographic variables: age and genderVariables related to classification of AF: AF was classified as paroxysmal when the arrhythmia was self-limiting and lasted less than 7 days. It was classified as persistent when it required electrical or pharmacological cardioversion or if it lasted longer than 7 days. AF was permanent if a rhythm- or rate-control strategy was not adopted for its management. To simplify calculations, the sample was divided into 2 groups, one with those patients with paroxysmal AF and the other with those patients with persistent and permanent AF, due to its continuous nature.

Variables related to the CHA2DS2-VASc scoring system: aged between 65 and 74, female, transient ischaemic attack (TIA) or thromboembolism, congestive heart failure and/or left ventricular dysfunction, hypertension (having SBP >140 and/or DBP >90mmHg), diabetes mellitus (according to the American Heart Association diabetes criteria) and prior myocardial infarction and/or peripheral artery disease. Each of these factors was assigned one point, except when the patient had suffered a previous stroke and/or was aged >75, in which case they were assigned two points. Based on the score obtained, patients were classified as being at high risk (≥2 points), moderate risk (1 point) and low risk (0 points) of suffering thromboembolic episodes, according to the scale's scoring criteria.

Variables related to the HAS-BLED scoring system: age ≥65; uncontrolled blood pressure (systolic blood pressure ≥160mmHg); impaired renal function (haemodialysis, kidney transplant, serum creatinine ≥2.2mg/dl or MDRD <60ml/min/1.73m2); impaired hepatic function (chronic liver disease, bilirubin twice the upper limit of normal and/or transaminases 3 times the upper limit of normal); history of significant bleeding or predisposition to bleeding; prescription of concomitant drugs that increase the risk of bleeding (drugs prescribed to the patient for chronic conditions were considered): acetylsalicylic acid, amiodarone, disulfiram, lovastatin, omeprazole, piroxicam, propranolol, tamoxifen; record of alcohol abuse (if documented in medical records); labile INRs (not contemplated since this information was not available at the start of the study as it was calculated during the results part). Once these variables were recorded, the HAS-BLED score was obtained by assigning each factor one point and classifying patients as having a low or high risk of bleeding (if the score was <3 or ≥3 points, respectively).

Variables related to prescribed treatment according to the following categories: vitamin K antagonists, direct-acting anticoagulants (with no distinction among them), antiplatelet therapy and those patients with no anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy.

Variables derived from anticoagulation control: time in therapeutic range. INR control was considered to be adequate when time in therapeutic range was equal to or greater than 60%. This is defined as the percentage of INR values within therapeutic range over 6 consecutive months.22,32

To all intents and purposes, information relating to the identity of patients is considered confidential. Data were collected in accordance with current ethical guidelines on the principles of confidentiality (according to Law 14/2007). Data were saved in the electronic medical records as secure, anonymous data, with an assigned code (patient number), so that only the investigator could link these data to an identified or identifiable person.

Statistical analysisQualitative variables were expressed as an exact value and percentage, while quantitative variables were expressed as the mean and standard deviation. The association between qualitative variables was examined using the chi-square test (comparison of proportions), the linear trend was analysed using the Mantel-Haenszel test and means were compared using Student's t-test for independent groups. In order to assess which variables with high thromboembolic risk were associated with a poor INR range, the crude odds ratios and odds ratios adjusted for those variables with good theoretical justification were calculated, but without exceeding 10 events per variable in order to avoid unstable models. Statistical significance was set at p≤0.05. The statistical analysis used the SPSS 20.0 software programme.

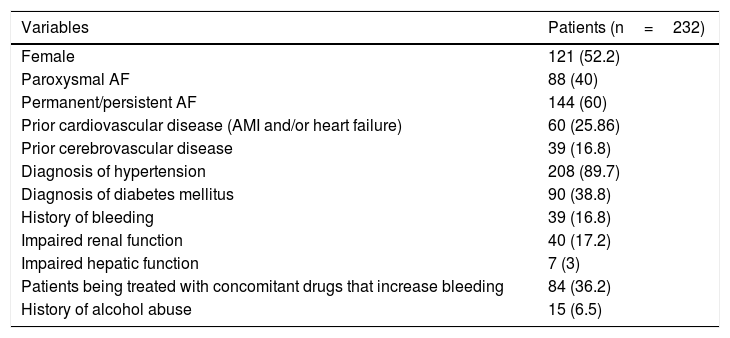

ResultsThe study included 232 patients diagnosed with AF. The prevalence of AF in the population of the health area included in the study was 1.05%. The mean age was 76.4±6.5 years (range 30–96 years). The mean age was 78.7±5.7 years for women and 73.7±8.3 years for men (p=0.005). Table 1 shows the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of the population studied, with a predominance of cases of permanent/persistent AF (60%). Most of the patients had normal renal (79.3%) and hepatic function (87.1%).

Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of the study sample.

| Variables | Patients (n=232) |

|---|---|

| Female | 121 (52.2) |

| Paroxysmal AF | 88 (40) |

| Permanent/persistent AF | 144 (60) |

| Prior cardiovascular disease (AMI and/or heart failure) | 60 (25.86) |

| Prior cerebrovascular disease | 39 (16.8) |

| Diagnosis of hypertension | 208 (89.7) |

| Diagnosis of diabetes mellitus | 90 (38.8) |

| History of bleeding | 39 (16.8) |

| Impaired renal function | 40 (17.2) |

| Impaired hepatic function | 7 (3) |

| Patients being treated with concomitant drugs that increase bleeding | 84 (36.2) |

| History of alcohol abuse | 15 (6.5) |

AF: atrial fibrillation; AMI: acute myocardial infarction.

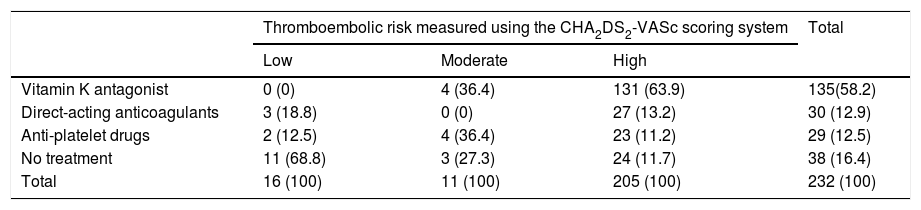

With regard to thromboembolic risk according to the CHA2DS2-VASc scoring system, as can be observed in Table 2, 205 patients (88.4%) had a high thromboembolic risk, 11 patients (4.7%) had a moderate risk and 16 patients (6.9%) had a low risk. Of those patients deemed to be at moderate risk (CHA2DS2-VASc=1 point), 4 had this score simply due to being female.

Association between thromboembolic risk and anticoagulation.

| Thromboembolic risk measured using the CHA2DS2-VASc scoring system | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Moderate | High | ||

| Vitamin K antagonist | 0 (0) | 4 (36.4) | 131 (63.9) | 135(58.2) |

| Direct-acting anticoagulants | 3 (18.8) | 0 (0) | 27 (13.2) | 30 (12.9) |

| Anti-platelet drugs | 2 (12.5) | 4 (36.4) | 23 (11.2) | 29 (12.5) |

| No treatment | 11 (68.8) | 3 (27.3) | 24 (11.7) | 38 (16.4) |

| Total | 16 (100) | 11 (100) | 205 (100) | 232 (100) |

Figures are expressed as exact value and (percentage). Groups were compared using the chi-square test (p<0.001). Mantel-Haenszel test: p<0.001.

Of the total of 232 patients, 17 patients (7.3%) had a high risk of bleeding, while 170 (73.3%) had a low risk of bleeding. This risk could not be calculated for 45 patients (19.4%) due to missing one or more of the parameters required to calculate the HAS-BLED score.

Table 2 shows the distribution of anticoagulation therapy. Of the total of 232 patients, 135 (58.2%) were being treated with vitamin K antagonists, 30 patients (12.9%) were taking direct-acting anticoagulants and 29 (12.5%) were receiving antiplatelet drugs. The remaining 38 patients (16.4%) had not been prescribed any antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy.

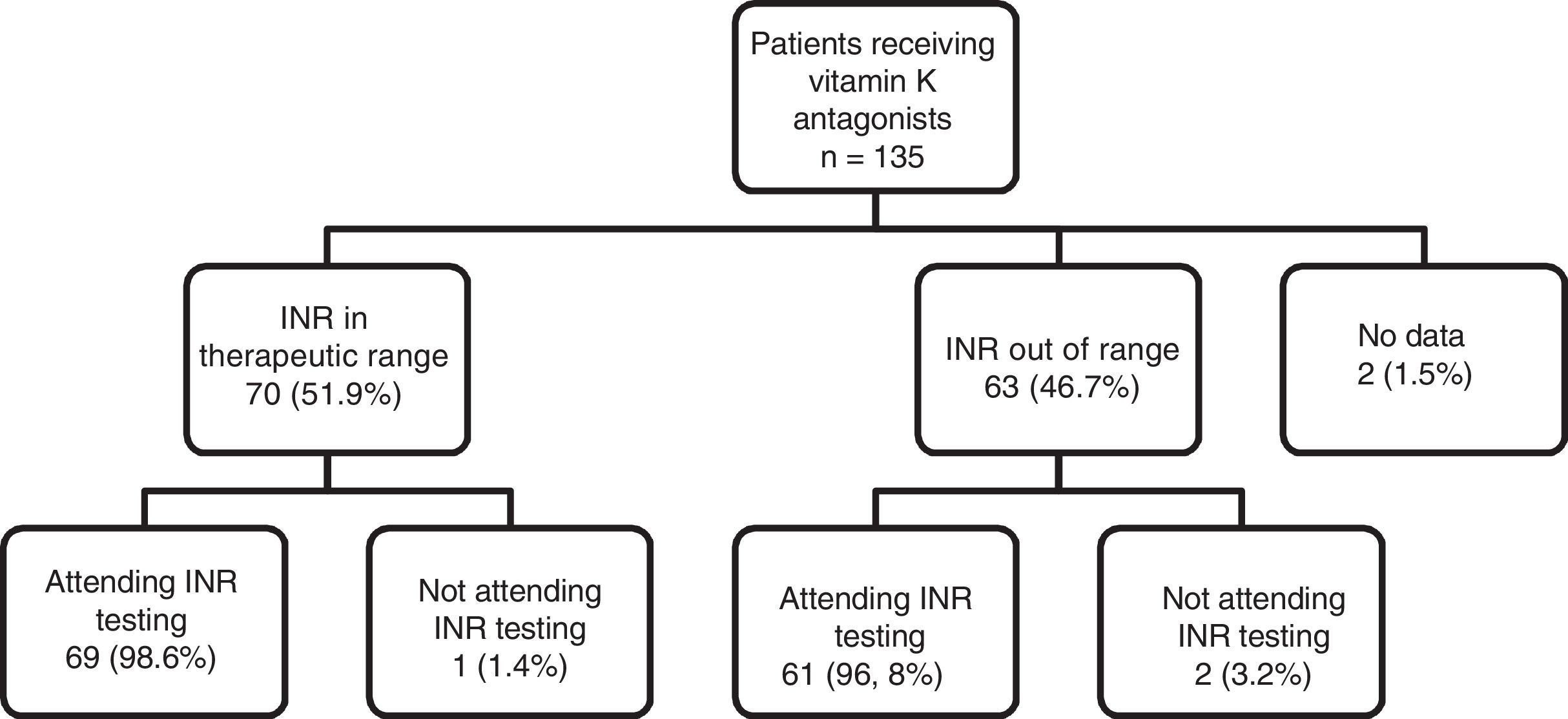

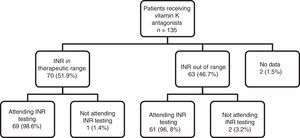

As can be observed in Fig. 1, the percentage of patients with good INR control (51.9%) was higher than the percentage of patients with poor control (46.7%). With regard to adherence to INR testing and dose adjustment schedules, of the total number of patients being treated with vitamin K antagonists (n=135), 130 (96.29%) showed good adherence to INR testing and dose adjustment schedules (they attended appointments on the right day), 3 patients (2.2%) did not show up for testing on the right day and there is no information for 2 patients (1.5%). This figure shows the distribution of adherence to INR testing, indicating that almost all patients who are in therapeutic range attend their INR testing and dose adjustment appointments (98.6%), compared to a slightly lower percentage of patients (96.8%) who do not have good INR control, but with no clinically and statistically significant differences.

With regard to the therapy prescribed for patients with thromboembolic risk, based on the CHA2DS2-VASc scoring system, the following results were obtained: 63.9% of patients at high thromboembolic risk were anticoagulated with vitamin K antagonists, compared to 36.4% of patients at moderate risk and none at low risk. Direct-acting anticoagulants were prescribed to 13.2% of high-risk patients, 18.8% of low-risk patients and no moderate-risk patients. Antiplatelet drugs, however, were only prescribed to 12.5% of patients at low thromboembolic risk compared to 11.2% at high risk and 36.4% at moderate risk. Up to 68.8% of patients at low risk were not prescribed any anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy compared to 27.3% of patients at moderate risk and 11.7% at high risk (p<0.001). Table 2 shows these data. Of all the patients receiving anticoagulant therapy, 43 (26.1%) were also taking concomitant antiplatelet therapy.

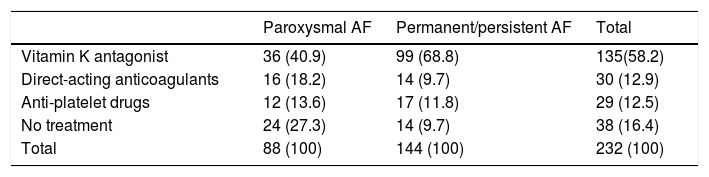

Table 3 shows the treatments prescribed according to type of AF, where almost twice the percentage of patients with permanent/persistent AF were treated with vitamin K antagonists compared to patients with paroxysmal AF. More patients diagnosed with paroxysmal AF were prescribed direct-acting anticoagulants and antiplatelet therapy alone than those patients with permanent/persistent AF (p<0.001).

Treatment prescribed according to permanent/persistent or paroxysmal atrial fibrillation.

| Paroxysmal AF | Permanent/persistent AF | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin K antagonist | 36 (40.9) | 99 (68.8) | 135(58.2) |

| Direct-acting anticoagulants | 16 (18.2) | 14 (9.7) | 30 (12.9) |

| Anti-platelet drugs | 12 (13.6) | 17 (11.8) | 29 (12.5) |

| No treatment | 24 (27.3) | 14 (9.7) | 38 (16.4) |

| Total | 88 (100) | 144 (100) | 232 (100) |

Figures are expressed as exact value and (percentage). Groups were compared using the chi-square test (p<0.001).

AF: atrial fibrillation.

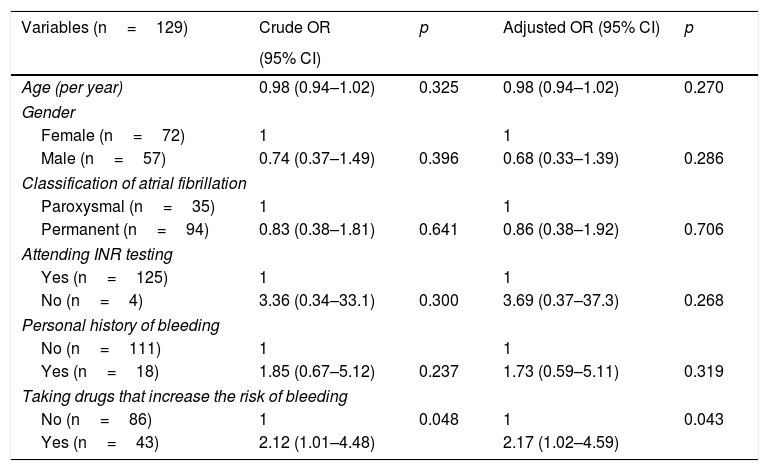

After determining that most patients were at high risk according to the CHA2DS2-VASc scoring system and that the INR of 46.7% of these was out of range, odds ratios were calculated in order to determine which variables may be related to poor INR control. As shown in Table 4, taking drugs that increase bleeding is closely associated with poor INR control (odds ratio 2.12 [1.01–4.48], p=0.048). After adjusting for variables that show greater theoretical justification (age, gender, classification of atrial fibrillation, adherence to INR testing, personal history of bleeding and taking drugs that increase bleeding), the relationship was still statistically significant (odds ratio 2.17 [1.02–4.59], p=0.043).

Crude odds ratio and odds ratio adjusted for different variables in those patients at high thromboembolic risk, according to the CHA2DS2-VASC scoring system, whose INR is not in therapeutic range.

| Variables (n=129) | Crude OR | p | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (95% CI) | ||||

| Age (per year) | 0.98 (0.94–1.02) | 0.325 | 0.98 (0.94–1.02) | 0.270 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female (n=72) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Male (n=57) | 0.74 (0.37–1.49) | 0.396 | 0.68 (0.33–1.39) | 0.286 |

| Classification of atrial fibrillation | ||||

| Paroxysmal (n=35) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Permanent (n=94) | 0.83 (0.38–1.81) | 0.641 | 0.86 (0.38–1.92) | 0.706 |

| Attending INR testing | ||||

| Yes (n=125) | 1 | 1 | ||

| No (n=4) | 3.36 (0.34–33.1) | 0.300 | 3.69 (0.37–37.3) | 0.268 |

| Personal history of bleeding | ||||

| No (n=111) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes (n=18) | 1.85 (0.67–5.12) | 0.237 | 1.73 (0.59–5.11) | 0.319 |

| Taking drugs that increase the risk of bleeding | ||||

| No (n=86) | 1 | 0.048 | 1 | 0.043 |

| Yes (n=43) | 2.12 (1.01–4.48) | 2.17 (1.02–4.59) | ||

CI: confidence interval for OR; n: number of participants in each subgroup; OR: odds ratio; p: significance level.

The prevalence of AF in our population was similar to that described in other studies.23–27

The results of our study show that 77.1% of patients with a high thromboembolic risk were anticoagulated compared to 81.3% (antiplatelet therapy, 12.5%, plus those who were not receiving any treatment, 68.8%) of low-risk patients who were not anticoagulated. In moderate-risk patients, 36.4% were anticoagulated with vitamin K antagonists. Treatment criteria or guidelines according to risk group are clearly established, except for patients with CHA2DS2-VASc=1, and it can therefore be stated that the dominant percentage of treatment prescribed in each group matches that suggested in the European Society of Cardiology Guidelines19 and the indications suggested for each score according to the Spanish Ministry of Health.22 It should be highlighted that 18.8% of low-risk patients are anticoagulated. This study has not been designed to evaluate other indications for anticoagulation that may be present in this percentage of patients. Nevertheless, there is a growing trend that supports assessing this group in which anticoagulation and all related risks could be avoided.19

The AFABE study27 observed half the number of patients with a CHA2DS2-VASC score <2 (5.9%) compared to those detected in this study (11.6%), with a slightly higher number of patients with a score ≥2 (94.1% versus 88.4% in this study). In both studies, the percentage receiving anticoagulation therapy and the percentage not receiving such therapy is very similar. With regard to the distribution of anticoagulation in low-risk patients, the percentages observed are not comparable since the AFABE study did not discriminate between patients with a score <2 on the scale.

Of the total number of patients in the study sample, it can be observed that 71.1% were taking anticoagulants, 12.5% were receiving antiplatelet drugs and 16.4% were prescribed no antiplatelet or anticoagulation therapy. Similar findings were obtained in the multi-centre FIATE study,28 in which, although the sample was admittedly much larger, the results associated with the percentage of patients receiving anticoagulation and antiplatelet drugs were not significantly different from the results obtained in this study.

Of the total number of patients anticoagulated with vitamin K antagonists, it can be said that only half (51.9%) had adequate INR levels. It can therefore be assumed that the other half had inadequate levels, either due to being too high or too low, with the risks that this situation involves. These results were obtained despite the fact that most (more than 90%) patients regularly attended their scheduled INR testing appointments. This situation seems to suggest that regular check-ups have no influence on adequate maintenance of suitable anticoagulation levels. It can be concluded that a large percentage of patients diligently attend their drug control appointments.

However, a large percentage of patients did not have adequate INR levels. Therefore, in accordance with indications given in the Ministry of Health's Therapeutic Positioning Report,22 it is recommended that treatment be modified to one of the direct-acting oral anticoagulants available. It must be remembered, however, that thromboembolic and bleeding risk must always be re-evaluated as these results will help establish appropriate individualised anticoagulation indications.

With regard to the prescription of drugs based on the type of AF (paroxysmal or permanent), prescription of vitamin K antagonists was almost twice as high for permanent AF than for paroxysmal AF in our study. However, this is the opposite of all other treatments (direct-acting oral anticoagulants or antiplatelet drugs alone), as these are prescribed more frequently for paroxysmal AF than for persistent/permanent AF.

In this study, most patients requiring INR monitoring were classified as being at high thromboembolic risk according to the CHA2DS2-VASc scale, which highlights the fact that a large part of this population (46.7%) was not within an adequate therapeutic range. Similar results are published in the ANFAGAL study,29 which show that the INR of more than 40% of anticoagulated patients was not in therapeutic range. Likewise, these findings are in line with other studies published on the Spanish population. In the CALIFA study,33 which analysed 1056 patients with chronic atrial fibrillation, being monitored by cardiologists, it was observed that only 60% of cases had adequate INR control. In one final study (PAULA), conducted in 1524 patients, anticoagulation was in therapeutic range for 60% of the follow-up time.30,32

In our study, the administration of drugs that increase bleeding was associated with poorer INR control, regardless of age, gender, type of atrial fibrillation, adherence to INR control and personal history of bleeding (odds ratio 2.17 [1.02–4.59], p=0.043). There are other studies that have evaluated the weight of polypharmacy and its association with INR control. Both the ANFAGAL study29 and the PAULA study32 reported worse anticoagulation control in patients taking multiple drugs concurrently (odds ratio 1.04 [1.01–1.07], p=0.005 in the PAULA study). However, the CALIFA study33 found worse INR control in patients taking NSAIDs (odds ratio 0.521 [0.352–0.773]; p=0.001) and antiplatelet drugs (odds ratio 0.472 [0.332–0.672], p<0.001). All of these data support the idea that polypharmacy results in worse INR control in patients taking vitamin K antagonists, which is highly relevant in this type of patient.

One of the main limitations of the study is the fact that the Rosendaal method was not used to calculate labile INR, which was instead calculated from the direct therapeutic time, although the Ministry of Health's Therapeutic Positioning Report22 includes this option for calculating labile INR. Also, studies have been published in which estimation of control range using the traditional and Rosendaal methods is interchangeable,31 and these identify similar cohorts of patients, such as the ANFAGAL study,29 which indicates precisely that measuring INR by counting in-range controls seems to be just as effective as the Rosendaal method.

Another of the main limitations is restricting population selection to one specific health area, which makes it difficult to extrapolate the data obtained to other areas. However, other published studies, such as the AFABE study,27 the FIATE study28 or the ANFAGAL study,29 describe similar epidemiological characteristics for their population to the ones presented in this study. The AFABE study included 135 female patients [49.8%] (compared with this study which included 121 [52.2%]) with a mean age of 78.9±7.33, which is similar to this study (76.4±6.5). It also had 62 patients with a history of heart failure [22.9%] (compared with 60 [25.86%] in our own), 39 with prior stroke [14.4%] and 8 with prior TIA [3%], with 40 in our study having prior cerebrovascular disease [14.7%].

Another major limitation of this study is the fact that data is missing from some medical records, which restricts actual calculation for the total number of patients, as is the case of the HAS-BLED scoring system, which has been especially affected, a setback that has not been experienced in those analyses with more data available. Therefore, the results and discussion of this study have been aimed predominantly at the CHA2DS2-VASc scoring system and not the HAS-BLED scoring system. As a result, AF has perhaps been underdiagnosed as this arrhythmia has been included under the code of another episode in the records. Another piece of information that was not available was the name of the doctor assigned to each patient, making it impossible to analyse the potential influence of this variable on INR control.

Finally, it is important to mention as a limitation the fact that each patient's degree of therapeutic compliance was not evaluated due to data being obtained from computer applications, which may have had an influence on inadequate INR control. Likewise, other variables that may affect the degree of control have also not been evaluated, although they have been shown to be important in other studies, such as the presence of severe chronic diseases (ANFAGAL study29) or hospital admissions (VARIA study34).

To conclude, of the total number of patients anticoagulated with vitamin K antagonists, only half (51.9%) had suitable INR levels, despite the fact that more than 95% of patients attended their scheduled control appointments. The percentage of patients with persistent or permanent AF prescribed vitamin K antagonists was observed to be almost twice that of patients with paroxysmal AF. Patient adherence to INR testing appointments was satisfactory, regardless of the degree of INR control.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed complied with the ethical standards of the responsible human experimentation committee and with the World Medical Association and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols implemented in their place of work regarding the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors obtained informed consent from the patients and/or subjects referred to in this article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

We would like to thank everyone who has contributed, either directly or indirectly, to this study and has made this article possible.

Please cite this article as: Aguilera Alcaraz BM, Abellán Huerta J, Carbayo Herencia JA, Ariza Copado C, Hernández Menárguez F, Abellán Alemán J. Valoración del tratamiento anticoagulante en pacientes diagnosticados de fibrilación auricular no valvular en una zona básica de salud. Clin Invest Arterioscler. 2018;30:56–63.