Therapeutic inertia (TI) is defined as the failure of the physician to initiate or intensify a treatment when the therapeutic goal has not been achieved. TI can be of 2 types: inertia due to lack of prescription of drugs and inertia in the absence of control of a risk factor. The consequences of TI are poor control of risk factors, an increase in potentially preventable events and an increase in costs. There are factors of the doctor himself, the patient and the care organisation that determine the presence of TI. Ten measures are proposed to reduce TI: to promote continuing education, to define clearly therapeutic objectives, to establish audits, to implement computerised medical records with alerts, to encourage research in this field, to disseminate clinical practice guidelines, to create motivational incentives, to organise care, to improve the doctor-patient relationship and to involve other health care providers.

Se define como inercia terapéutica (IT) el fallo del médico en iniciar o intensificar un tratamiento cuando no se ha conseguido el objetivo terapéutico. La IT puede ser de 2 tipos: la inercia por ausencia de prescripción de fármacos y la inercia ante la ausencia de control de un determinado factor de riesgo. Las consecuencias de la IT son un mal control de los factores de riesgo, un aumento de eventos potencialmente evitables y un aumento de los costes. Existen factores del propio médico, del paciente y de la organización asistencial que determinan la presencia de IT. Se proponen 10medidas para disminuirla: promover la formación continuada, marcar claramente los objetivos terapéuticos, establecer auditorías, implantar la historia clínica informatizada con alertas, incentivar la investigación en este campo, divulgar las guías de práctica clínica, crear incentivos motivadores, organizar la asistencia, mejorar la relación médico-paciente e implicar a otros agentes sanitarios.

Therapeutic inertia (TI) is defined as the failure of the physician to initiate or intensify treatment when the therapeutic target has not been achieved.1 TI, therefore, can only occur if there is a clear, preferably evidence-based, target and a treatment whose effect can be easily measured. Clinical inertia is a broader term that includes both TI and failure to diagnose or follow-up a patient.2 TI is common in the treatment of chronic diseases, such as diabetes, hypercholesterolaemia or hypertension, especially in the asymptomatic phases.

TI can lead to poorly controlled risk factors, an increase in potentially preventable events and, consequently, increased costs. TI is quantified as the percentage of patients whose pharmacological treatment is not modified divided by the total number of patients who have not achieved the control target.

There are 2 types of TI: inertia due to lack of prescription of drugs and inertia in the absence of control of a particular risk factor. For example, in a study carried out in Valencia, Spain, in more than 11,000 subjects with undiagnosed dyslipidaemia, no therapeutic action had been taken (failure to start treatment) in 38% who showed hypercholesterolaemia in at least 2 analyses.3 The REPAR Study, also conducted in Spain, included 140 cardiologists and more than 1100 patients with coronary disease. After one year of follow-up, 74% of the patients had LDL cholesterol >70mg/dl, and over half were receiving low- or moderate-intensity lipid-lowering treatment (failure to follow-up).4

Although TI is the responsibility of the physician, it occurs due to a number of factors, approximately 50% of which are physician-related, 30% patient-related, and 20% are related to the healthcare centre.1

Physician-related factorsLack of awareness of the therapeutic targets is a frequent cause of TI. Physicians tend to keep their patients close to what they believe is the therapeutic target; however, TI will occur if they are unaware that this target is incorrect.5 The optimistic view of the care provided tends to cause TI. In the HISPALIPID study involving more than 1600 physicians, a significant difference was observed between subjective control of dyslipidaemia (physician-perceived control) and objective or real control. This was due to misperception of the real level of control on the part of the physician.6 There is also evidence that more extensive academic training is associated with a lower rate of TI, and that the longer the doctor has been practising, the greater the TI.7 Finally, some authors have described a lower rate of TI among female physicians than their male counterparts.8

Patient-related factorsPatient-related factors associated with greater TI include more advanced age, female sex, comorbidity or concurrent disease, polymedication, primary prevention care, and the presence of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.1

Factors related with the healthcare centreThe organisation of consultations can play an important role in TI. The lower the number of patients seen each day, the lower the incidence of TI. The longer the duration of the visit, the more likely the physician is to modify the treatment and, therefore, reduce the incidence of TI.9 Finally, the limitations imposed by some Spanish regional health authorities on the use of certain lipid-lowering drugs has led to significant inter-regional differences in cholesterol control levels.4

TI is associated with certain physician profiles. In a recent study in France, the authors asked 125 physicians why they had not changed their patient's treatment despite not achieving therapeutic targets.10 Based on the answers received, they were able to identify 7 different types of TI that can be summarised in 4 physician profiles:

- -

Optimist: places great expectations only on the patient's lifestyle changes.

- -

Procrastinator: repeatedly re-evaluates the patient without deciding to change the treatment, negotiates slight modifications with the patient, or does not change the regimen because the patient has “almost” achieved the therapeutic target.

- -

Contextualiser: blames the results on abnormalities in measurement results or on the patient's personal or social situation (for example, they had a large meal the day before the test, or they have had a highly stressful week).

- -

Cautious: is fearful of adverse effects, or believes there is insufficient evidence to warrant a change of regimen.

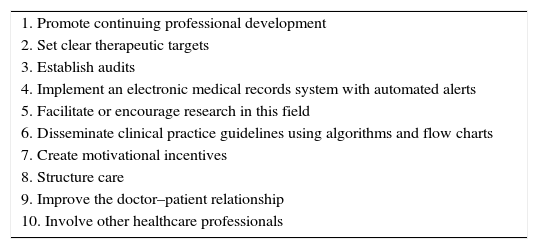

The list of measures is shown in Table 1.

Ten measures to reduce therapeutic inertia.

| 1. Promote continuing professional development |

| 2. Set clear therapeutic targets |

| 3. Establish audits |

| 4. Implement an electronic medical records system with automated alerts |

| 5. Facilitate or encourage research in this field |

| 6. Disseminate clinical practice guidelines using algorithms and flow charts |

| 7. Create motivational incentives |

| 8. Structure care |

| 9. Improve the doctor–patient relationship |

| 10. Involve other healthcare professionals |

Doctors are part of an ongoing process of teaching and learning, therefore, promoting continuing professional development is a good strategy to combat TI. There is evidence to show that knowledge and skills must be improved and attitudes must be changed in order to overcome TI. Goldberg et al. demonstrated the success of a training model focused on the importance of therapeutic compliance and other factors associated with the clinical management of hypercholesterolaemia.11 The model included several short group presentations given during staff meetings, along with a regular series of short educational messages sent by e-mail. Each e-mail was designed to be no more than a “screenshot” of information and was linked to an online forum for discussion with an expert. Following the educational intervention, physicians took a more proactive attitude towards reducing cholesterol levels, achieving a success rate of 62% compared to 49% observed before the training initiative.11 These results show the need to focus continuing professional development on TI in order to ensure that more patients achieve the therapeutic targets established for disease control.

Another important factor to analyse is the most appropriate and cost-effective training model to use. Although there are no overwhelming arguments in favour of any particular strategy, the choice will basically depend on the resources available and the factors (economic, geographic, accessibility, etc.) affecting the physicians to be trained. Classroom-based or on-line courses, attending scientific meetings and conferences, and training visits to specialised units can all improve quality of care and establish channels of communication and forums where professionals can pool their knowledge and ultimately reduce TI. Efforts should be made in the future to set up a variety of programmes, particularly based on non-traditional teaching methods, in order to achieve the best results.

Set clear therapeutic targetsCurrently, one of the major focuses of the scientific community is to ascertain the degree to which chronic disease is monitored and controlled. In their clinical practice guidelines, the different scientific societies set therapeutic targets in order to provide physicians with homogeneous recommendations for the appropriate management of patients with chronic disease. However, studies are regularly published showing that these targets are not achieved in the most prevalent chronic diseases in Spain. In the case of cardiovascular disease, for example, there is evidence of widespread under-treatment of dyslipidaemia, which is of particular concern in high-risk patients.12 Moreover, poor compliance with clinical practice guidelines occurs in both primary and secondary prevention. Although there are many health system-related factors that can contribute to TI, the pivotal role of the physician is reasonably clear. Since therapeutic targets have already been defined, we recommend that physicians discuss the situation with their patient and agree on the following strategies before prescribing treatment:

- -

Determine cardiovascular risk using individualised validated risk scales, and explain the meaning of the result obtained to the patient.

- -

Set therapeutic targets in accordance with the relevant guidelines and obtain an agreement with the patient. To do this, it is best to include short, easily understood information in the clinical report, clearly setting out the agreed targets and encouraging the patient to comply with the prescribed treatment to achieve the desired outcomes.

- -

Discuss with the patient the therapeutic strategy designed to achieve the desired target. To do this, the physician needs to explain the percentage reduction needed to be achieved, and why it is decided to select the most appropriate medication. In order to make this easier, various tables have been developed in recent years to help plan the best treatment and reduce TI.13,14

Although quality audits are rarely performed and are varied in the Spanish health system, interest in developing quality systems has increased in recent years. The aphorism “what is not evaluated becomes devalued” seems to apply in this case. Audits, however, make physicians feel uncomfortable, even though they probably devote more time than other professionals to continuing professional development, and are members of a profession in which greater scientific rigour prevails. Nevertheless, aside from the many factors we can blame for our shortcomings, TI is a sign of substandard professional performance. Therefore, the aim of audits should not be to make the physician feel scrutinised, but rather to obtain information about our clinical practice, to implement improvement measures, and, finally, to encourage us to continuously improve our quality of care. For this reason, we call on physicians to perform a systematic self-evaluation of their clinical practice (self-audit) to determine the degree to which their patients’ disease is controlled, and then compare the results obtained with those of other colleagues working nearby or from other regions. We also suggest organising interactive sessions with specialists or opinion leaders to discuss the results obtained and obtain the tools needed to achieve targets. Audits are not the ideal instrument for evaluating TI because it is hard to quantify inertia. This is partly due to the lack of validated, disease-specific indicators. Another difficulty is the lack of criteria to define the time period between obtaining test results and modifying treatment, since this can be done during the same medical visit or at a subsequent visit. This lack of homogeneity in the presentation of results makes it difficult to compare the results of studies in TI. Finally, it is important to emphasise the need for feedback at the end of both internal and external audits. This will allow physicians to analyse their own clinical practice and, if needed, reduce their TI.

Implement an electronic medical records system with automated alertsElectronic medical records are not only useful from an administrative point of view, they can also improve the quality of care by facilitating research studies, clinical audits and teamwork. In a systematic review of 257 studies, Chaudhry et al. showed that electronic records also facilitated clinical guideline-based decision making.15 In the field of cardiovascular diseases, specifically, electronic decision support systems improve adherence to guidelines by between 12% and 20%, particularly in primary and secondary prevention.15

In order to reduce TI, electronic medical records can include an automated alert system that informs the physician of the therapeutic targets, and whether these have or have not been achieved. A study of more than 80,000 patients, involving 77 physicians, evaluated the efficacy of using electronic alerts in decision-making in the management of dyslipidaemia. To do so, the authors compared electronic alerts against on-demand expert advice and no intervention (control group),16 observing that 66% of patients attended by physicians assigned to the electronic alert group received the correct treatment compared to 40% in the on-demand advice group, and 36% in the control group.16 This shows that electronic alert systems improve control of dyslipidaemia, and are therefore a useful tool to combat TI. Electronic alerts, moreover, allow the physician to make decisions immediately in the presence of the patient, without the need to defer therapeutic decisions. It should be noted, however, that too many alerts can be overwhelming, and physicians will tend to ignore them.

Facilitate or encourage research in this fieldAny study or research project aimed at documenting TI, evaluating attitudes to this phenomenon among physicians, analysing clinical practice variability, and proposing action criteria to reduce or eliminate TI are strategies that will undoubtedly improve clinical efficiency, with a subsequent improvement in quality of care. In recent years, various projects have been launched to investigate TI in the most prevalent diseases (dyslipidaemia, diabetes, hypertension, etc.). While initiatives aimed at determining the factors involved in TI (diagnostics, clinical and therapeutic) have been interesting enough, there is a more pressing demand for projects aimed specifically at identifying models of action and strategies to break TI habits and improve efficiency in the care of patients with dyslipidaemia.

Funding is a far from insignificant factor in research. Health care institutions should be aware of this, and support quality research that may be key to improving the quality of clinical practice. Projects such as DILEMA17 can be a springboard to raise awareness of these tools in the management of dyslipidaemia.

Disseminate clinical practice guidelines using algorithms and flow chartsThe dissemination of medical information alone is not effective in reducing TI, as practitioners often spend little time reviewing the latest medical literature. New information obtained from clinical trials is substantiated and summarised in clinical practice guidelines; however, the extent and complexity of some of these may prevent them from being applied in daily clinical practice, above all in multidisciplinary fields. Presenting these guidelines in the form of flow charts, synoptic tables and algorithms may facilitate achievement of established therapeutic targets, but, in general, it is important to bear in mind that although different educational interventions and academic training for medical professionals can improve clinical outcomes, the changes they bring about are short-lived.18 It would be interesting to include these algorithms in computer applications and digital systems that would enable physicians to access them from their smartphone or tablet.

Create motivational incentives (not just financial)Several observational studies have shown that creating financial incentives for achieving targets is an effective, though short-lived, strategy. Achievements are maintained while the financial compensation is available. An illustration of this is the study published by O’Connor et al.19

Financial incentives can sometimes backfire by promoting strategies that stand in the way of achieving targets, such as encouraging the use of cheaper but less potent drugs, or limiting the use of more expensive but more effective combinations.

Management bodies do not always possess the imagination needed to create non-financial incentives, such increasing human or material resources, more time for study or research, encouraging attendance at conferences, etc. These incentives, however, should never increase the workload of the rest of the staff, such as duplicating consultations or preventing physicians from standing in for absent colleagues.

Structure care. Adjust the workloadStructuring the medical consultation can reduce TI. According to Giugliano et al.19, patient visits should be structured along the lines of a clinical trial. The physician should start by reviewing the medical history of each patient before the visit to determine whether targets have been achieved or a change of treatment is required, and consider the possible interactions and adverse effects. Finally, any changes made should be documented and justified in order to reduce TI. The feasibility of this approach will depend on each physician's workload, but it is not clear whether a smaller number of patients seen per day is associated with a better compliance of guidelines. Some authors argue that reducing the number of patients seen per day improves compliance with guidelines,20 but others disagree.21 This controversy merits further research, particularly considering that the greater the gap between diagnosis, treatment modification and start of the new regimen, the greater the risk of TI.

Another organisational strategy that appears to reduce TI in Primary Care involves separating scheduled appointments from “drop-in” consultations, since the latter have been shown to increase TI. Similarly, consulting for various problems (hyper-frequent visits and comorbidities) results in fewer changes or treatment adjustments, which also increases TI.22

Improve the doctor–patient relationshipThis is an additional part of the foregoing strategy, since organisational improvement will no doubt help improve the doctor–patient relationship.

In Primary Care, and also in Internal Medicine to a certain extent, consultations for chronic diseases, above all, involve less risk but greater uncertainty. The doctor–patient relationship is a long-lasting association, so the problems discussed in previous appointments will determine the approach taken in successive visits. This is why it is so difficult to estimate TI on the basis of a single clinical interview.23

Certain patient characteristics are associated with, and can even promote, greater TI. For example, more advanced age, female sex and comorbidities are factors associated with greater TI. It is crucial to educate patients, explain the therapeutic targets sought, and detect cases of denial of disease or mistrust (frequent change of doctor, residents, rotations, etc.).24

Involve other healthcare professionalsAlthough ultimately, and by definition, TI stems from one medical act, care processes are no longer the exclusive domain of doctors. TI can be reduced by involving other healthcare providers. Indeed, the health professional-patient relationship is key to maintaining not only therapeutic adherence, but also to setting non-pharmacological goals, such as diet, physical exercise or giving up toxic habits.

Effective communication between doctors and nurses can help detect clinical inertia in the context of non-pharmacological measures, which, as discussed above, is a first step in almost all protocols, particularly in a work environment excessively focussed on pharmacological measures. For some time now, nurses have played an important role in “prescribing” therapies or heart-healthy lifestyles that help achieve therapeutic goals. Although there is scant research on this topic,20 nurses, aside from contributing to therapeutic compliance and reducing clinical inertia, could also be called on to detect and report cases of TI in the aforementioned cases.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were conducted on human beings or animals for this research.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The 10 proposals included in this decalogue were discussed and voted by delegates attending the 4th Meeting of Lipid Clinics of the Spanish Atherosclerosis Society, held in San Sebastián on 2 and 3 March 2017, with the following results: 1 was approved by 94.8% of votes; 2 by 98.2% of votes; 3 by 99.1% of votes; 4 by 58.4% of votes; 5 by 75.0% of votes; 6 by 96.0% of votes; 7 by 86.3% of votes; 8 by 90.5% of votes; 9 by 89.5% of votes, and 10 by 77.3% of votes.

Please cite this article as: Blasco M, Pérez-Martínez P, Lahoz C. Decálogo de la Sociedad Española de Arteriosclerosis para disminuir la inercia terapéutica. Clin Invest Arterioscler. 2017;29:218–223.