The prevention of cardiovascular disease is based on the detection and control of cardiovascular risk factors (CVRF). In Spain there are important geographical differences both in the prevalence and in the level of control of the CVRF. In the last decade there has been an improvement in the control of hypertension and dyslipidaemia, but a worsening of cardio-metabolic risk factors related to obesity and diabetes.

The SIMETAP study is a cross-sectional descriptive, observational study being conducted in 64 Primary Care Centres located at the Community of Madrid. The main objective is to determine the prevalence rates of CVRF, cardiovascular diseases, and metabolic diseases related to cardiovascular risk. A report is presented on the baseline characteristics of the population, the study methodology, and the definitions of the parameters and diseases under study. A total of 6631 study subjects were selected using a population-based random sample. The anthropometric variables, lifestyles, blood pressure, biochemical parameters, and pharmacological treatments were determined.

The highest crude prevalences were detected in smoking, physical inactivity, obesity, prediabetes, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemias, and metabolic syndrome. A detailed analysis needs to be performed on the prevalence rates, stratified by age groups, and prevalence rates adjusted for age and sex to assess the true epidemiological dimension of these CVRF and diseases.

La prevención de la enfermedad cardiovascular se fundamenta en la detección y control de los factores de riesgo cardiovascular (FRCV). En España existen importantes diferencias territoriales tanto en la prevalencia como en el grado de control de los FRCV. En la última década ha habido una mejora del control de la hipertensión y la dislipidemia, pero un empeoramiento de los factores de riesgo cardiometabólicos relacionados con la obesidad y la diabetes.

El estudio SIMETAP es un estudio observacional descriptivo transversal realizado en 64 centros de atención primaria de la Comunidad de Madrid. El objetivo principal es determinar las tasas de prevalencia de FRCV, de las enfermedades cardiovasculares y de las enfermedades metabólicas relacionadas con el riesgo cardiovascular. El presente artículo informa sobre las características basales de la población, la metodología del estudio, y las definiciones de los parámetros y enfermedades en estudio. Se seleccionaron 6.631 sujetos de estudio mediante una muestra aleatoria base poblacional. Se determinaron variables antropométricas, estilos de vida, presión arterial, parámetros bioquímicos, y tratamientos farmacológicos.

Las prevalencias crudas más elevadas se detectaron en tabaquismo, inactividad física, obesidad, prediabetes, diabetes, hipertensión, dislipidemias y síndrome metabólico. Para valorar la verdadera dimensión epidemiológica de estas enfermedades y FRCV, es necesario realizar un análisis pormenorizado de tasas de prevalencia estratificadas por grupos etarios y de las tasas de prevalencia ajustadas por edad y sexo.

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (CVD) can be considered the result of a pathogenic continuum involving an unhealthy lifestyle and multiple cardiovascular risk factors (CVRF). The clinical manifestations of CVD are the leading cause of death in the western world. It is therefore a priority that we implement high-impact healthcare interventions to reduce cardiovascular risk (CVR).

The Spanish adaptation1 of the European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice2 recommend prior screening to assess CVR, promoting healthy lifestyles and intervening in CVRF and CVD-related syndromes and disorders with an intensity proportional to the pre-established CVR.

These considerations can also be applied in clinical conditions related to insulin resistance (IR) such as prediabetes, diabetes mellitus (DM), chronic kidney disease (CKD), familial combined hyperlipidaemia, metabolic syndrome (MetSyn) and obesity. The European guidelines2,3 place great emphasis on the fact that patients with DM are at high or very high CVR, and the consensus of American endocrinology associations4 considers CVR to be extreme if CVD is associated with DM or CKD.

Continued action of the most important CVRF, such as smoking, hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia, causes deterioration of the vascular endothelium, favouring the formation, oxidation and vulnerability of atherosclerotic plaque, until clinical manifestation of CVD in the form of coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke or cerebrovascular accidents (CVA), or peripheral arterial disease (PAD).

Patients with IR-related conditions have a particularly high CVR because they have a characteristic lipid profile which accelerates the atherosclerosis process known as atherogenic dyslipidaemia. This lipid phenotype is characterised by low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), hypertriglyceridaemia (HTG) and non-high levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), although with a high concentration of LDL particles with apolipoprotein B, which are typically small and dense.5 Given its importance in aetiopathogenic terms, we need to assess the different phenotypic expressions of lipid profiles and IR in patients suffering from clinical or metabolic manifestations of CVD or DM.

The concept of MetSyn6 emerged almost 40 years ago to define a non-coincidental grouping of factors associated with IR observed in clinical practice: central obesity, dyslipidaemia, abnormalities in glucose metabolism and hypertension. MetSyn is of particular importance because it increases the risk of DM,7,8 CVD,8 and CKD.9 MetSyn increases all-cause mortality rates and doubles the risk of suffering CVD.8 Even if the most commonly used definitions of MetSyn10–13 excluded DM from among the diagnostic criteria, the increased risk of suffering from CVD would be maintained.

Probably the best thing we can do is accept that MetSyn covers a group of individuals in whom some of the criteria may be absent, but who have a high CVR, and that this would not be detected if we did not consider the overall view. Hence the dual importance of MetSyn. On the one hand, it serves to alert the physician to look for other CVRF in patients with a particular cardiometabolic risk factor. While on the other, it can identify a large number of subjects with high CVR who need intervention with both medical and public health strategies. The WHO experts14 consider that the key action on MetSyn needs to focus on health policies based in primary healthcare.

However, studies on prevalence have encountered several conceptual issues. One is understanding that MetSyn is a cluster of factors which are associated with CVRF, CVD and the related morbidity of IR. Another is the fact that there are a number of definitions of MetSyn that include classic CVRF and other cardiometabolic risk factors which are considered differently depending on the scientific society.10–13 Moreover, as the definitions of MetSyn do not currently appear in the episode coding of the International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC-2)15 or in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9),16 it is not easy to record an episode of MetSyn in the patient's medical records. Nor do the codes in the ICPC-2 (K22) or the ICD-9 (277.7; 277.9) specifically refer to any of the existing definitions of MetSyn. This causes difficulties in terms of detecting MetSyn, assessing the patient's overall CVR, and comprehensive intervention on all cardiovascular and cardiometabolic risk factors related to MetSyn.

CVD prevention requires prior assessment of the epidemiology of all the factors that can influence the problem to be evaluated. In turn, to make an adequate health diagnosis, we need to know the prevalence in all age groups of the study population. Following this strategy of action, the aim of the SIMETAP study was to determine the prevalence rates, adjusted for age and gender, of CVRF, CKD, CVD and CVD-related metabolic diseases in the adult population of the Madrid Region.

Material and methodsStudy design and populationThe SIMETAP study was an observational, descriptive, cross-sectional study conducted by 121 general practitioners from 64 primary care centres run by the Public Health Service for the Madrid Region (SERMAS). The study was carried out according to the principles established by the 18th World Medical Assembly (Helsinki, 1964) and its amendments, and by the International Conference on Harmonization and guidelines for good clinical practice. The Research Commission of the Madrid Region Primary Care Management Department for Planning and Quality issued a favourable opinion for the study to be conducted.

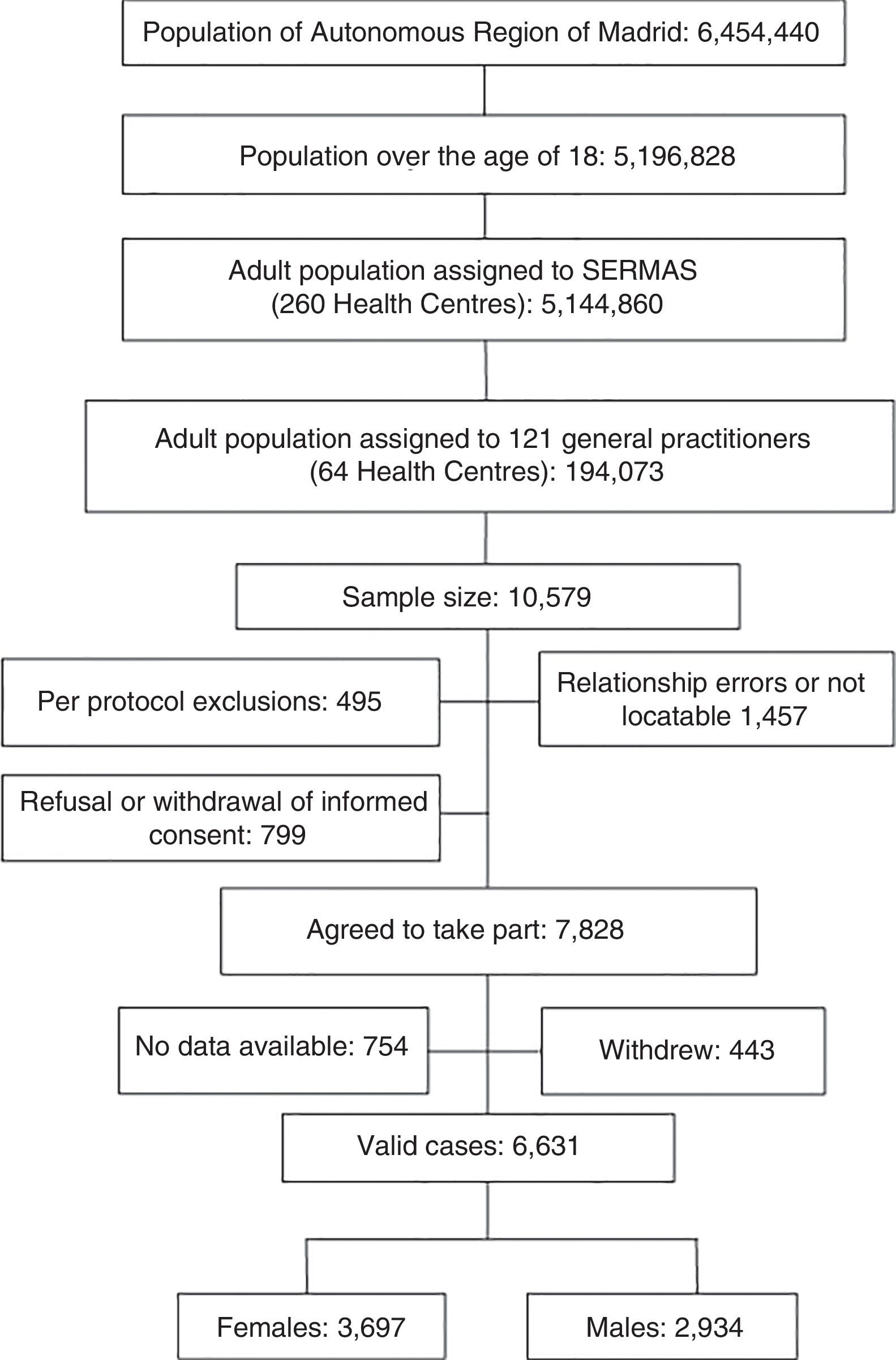

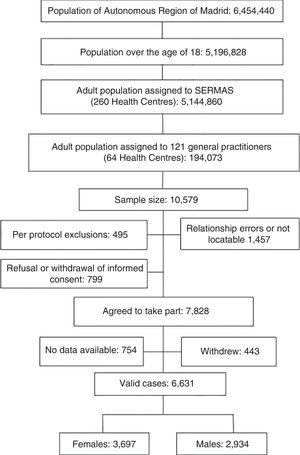

The population assigned to SERMAS was 5,144,860 adults (99% of the population census), whose healthcare was provided in 260 primary care centres. A representative sample (10,579 adults) was obtained based on the population assigned to general practitioners aged 18 or over, with no upper age limit (194,073 adults). The sample size was calculated with this finite population for a confidence level of 95% (α error), 0.024 for the confidence interval (margin of error of 1.2%), p=0.5 for the expected proportion, and considering 25% for lack of response and 14% for losses and dropouts.

To obtain the sample population, we used tables of random numbers generated by the Microsoft© Excel© 2013 program. These were applied to randomly sort the lists of patients assigned to general practitioners and to select the subjects for the study.

Institutionalised and terminally ill patients, pregnant women and patients with cognitive impairment were excluded from the study as per protocol. Through an active search of the subjects in the resulting sample, the investigators made up to five telephone calls to contact them and invite them to take part in the study.

Data collectionAfter obtaining the signed consent, the investigators conducted a clinical interview with the study subjects to gather information on age, gender, healthy lifestyles, anthropometric measurements, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, CVRF, history of metabolic disorders, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cardiovascular disease (CHD, stroke, PAD, heart failure, atrial fibrillation), erectile dysfunction, CKD, albuminuria, drug treatments and most recent biochemical parameters determined from blood and urine tests over the previous year. The investigators collected the study data from January to December 2015. Double entry of data guaranteed registration in the database.

Definition of variablesFor the purposes of this study, patients were considered to suffer from the syndromes and diseases under study if their respective diagnoses or their related ICPC-215 or ICD-916 codes were registered in their medical records, considering the following definitions and diagnostic criteria:

Smoking: Consumption of any number of cigarettes or tobacco in the last month.

Former smoker: Patient who has not smoked for over a year.

Alcoholism: Regular consumption of alcohol >21 units (210g) per week in males and >14 units (140g) per week in females.

Lack of physical exercise: Less than 150min physical exercise in one week.

High blood pressure (ICPC-2: K85): Systolic blood pressure ≥130mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥85mmHg without a diagnosis of hypertension.17

Hypertension (ICPC-2: K86, K87. ICD-9: 401–404): Systolic blood pressure ≥140mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90mmHg,17 or if the patient was taking medication to reduce blood pressure.

Marked hypertension: Blood pressure ≥180/110mmHg.

Prediabetes (ADA: American Diabetes Association)18 (ICPC-2: A91. ICD-9: 271.3): Without criteria for DM, fasting plasma glucose (FPG) from 100mg/dl (5.6mmol/l) to 125mg/dl (6.9mmol/l) both inclusive, or glycosylated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) from 5.7% (39mmol/mol) to 6.4% (47mmol/mol), both inclusive.

Prediabetes (CDA: Canadian Diabetes Association)19 (ICPC-2: A91. ICD-9: 271.3): Without criteria for DM, FPG from 110mg/dl (6.1mmol/l) to 125mg/dl (6.9mmol/l) both inclusive, or HbA1c from 6% (42mmol/mol) to 6.4% (47mmol/mol), both inclusive.

DM Type 1 (ICPC-2: T89. ICD-9: 250.01). ADA18 or CDA19 criteria.

DM Type 2 (ICPC-2: T90. ICD-9: 249; 250.02): ADA18 or CDA19 criteria. FPG ≥126mg/dl (7mmol/l) or HbA1c ≥6.5% (48mmol/mol).

Hypercholesterolaemia (ICPC-2: T93. ICD-9: 272.0; 272.2; 272.4): Serum total cholesterol (TC) ≥200mg/dl (5.17mmol/l), or if the patient was taking medication to reduce their cholesterol.

Marked hypercholesterolaemia: Serum TC ≥300mg/dl (7.76mmol/l), or LDL-C ≥190mg/dl (4.91mmol/l), or if the diagnosis of familial hypercholesterolaemia or familial combined hyperlipidaemia was registered in the patient's medical records.

HTG10 (ICD-9: 272.1; 272.3): Serum triglycerides (TG) ≥150mg/dl (1.69mmol/l), or if the patient was taking medication to reduce their TG.

High HDL-C: Serum HDL-C ≥60mg/dl (1.55mmol/l).

Low HDL-C: Serum HDL-C<40mg/dl (1.03mmol/l) in males or<45mg/dl (1.16mmol/l) in females.5 HDL-C<50mg/dl (1.29mmol/l) was also considered in females.10–13 Non-HDL cholesterol: Difference between serum TC and HDL-C.

LDL-C: Determined with the Friedewald formula (LDL-C=TC - [HDL-C] - TG/5) if TG were<400mg/dl (<4.52mmol/l).20

Very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol: TC−(HDL-C)−(LDL-C).

Atherogenic dyslipidaemia5: HTG with low HDL-C.

Castelli index-I21: TC/HDL-C.

Castelli index-II21: LDL-C/HDL-C

Atherogenic non-HDL cholesterol/HDL-C coefficient.

TG/HDL-C ratio.

Atherogenic index of plasma22: log (TG/HDL-C).

TG and glucose index23: Ln [TG (mg/dl)×FPG (mg/dl)/2]

Overweight24 (ICPC-2: T83. ICD-9: 278.02): body mass index (BMI) from 25.0 to 29.9kg/m2.

Obesity24 (ICPC-2: T82; ICD-9: 278.00; 278.01): BMI (weight/height2) ≥30kg/m2.

Abdominal or central obesity: Waist circumference ≥102cm in males or ≥88cm in females,13 and ≥94cm in males and ≥80cm in females,12 measured with the subject in a standing position using a flexible tape measure tightened without compressing the skin, at the end of a normal expiration, locating the upper edge of the iliac crests and, above that point, surrounding the waist parallel to the floor.24

Waist-to-height ratio25 (WHtR): Waist circumference/height (cm/cm).

Hypothyroidism (ICPC-2: T86; ICD-9: 244.9) on replacement therapy.

Hepatic steatosis (ICD-9: 571.8) registered in medical records.

CHD (ICPC-2: K74, K75, K76. ICD-9: 410–414): Includes ischaemic heart disease, prior acute myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndromes, coronary artery bypass and other arterial revascularisation procedures.

CVA (ICPC-2: K89, K90; K91. ICD-9: 430; 431–436): It includes cerebrovascular accident, cerebral ischaemia or intracranial haemorrhages and transient ischaemic attack.

PAD (ICPC-2: K92. ICD-9: 440; 443.9; 444): Also includes intermittent claudication and an ankle/brachial index ≤0.9.

CVD: Includes CHD, CVA and PAD.

Heart failure (ICPC-2: K77. ICD-9: 428).

Atrial fibrillation (ICPC-2: K78. ICD-9: 427.3).

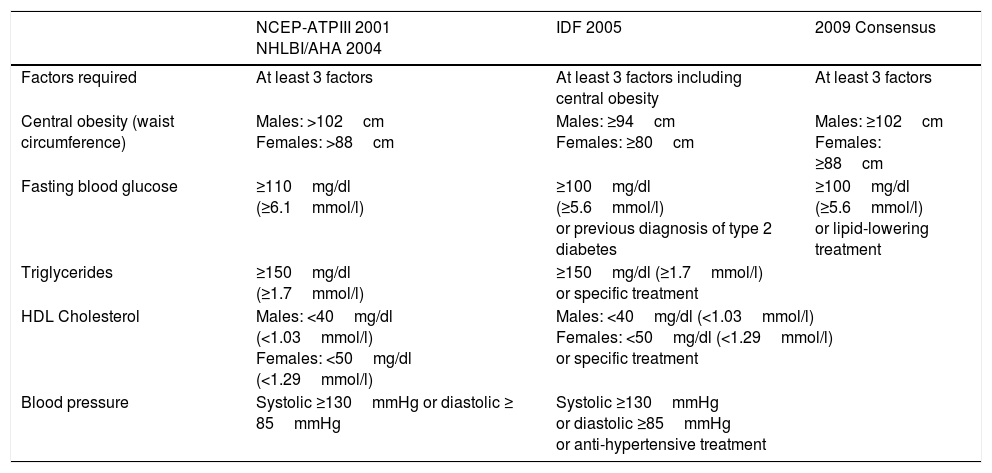

MetSyn (ICPC-2: K22. ICD-9: 277.7; 277.9): Three concepts were considered: The National Cholesterol Education Program-Adult Treatment Panel III10 definition (NCEP-ATPIII), maintained by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association11 (NHLBI/AHA); the definition of the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) for the European population12; and the harmonised consensus13 definition of MetSyn for the European population established by the following scientific societies: IDF, Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; NHLBI; AHA; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity (Table 1).

Definitions of metabolic syndrome for the European population.

| NCEP-ATPIII 2001 NHLBI/AHA 2004 | IDF 2005 | 2009 Consensus | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factors required | At least 3 factors | At least 3 factors including central obesity | At least 3 factors |

| Central obesity (waist circumference) | Males: >102cm Females: >88cm | Males: ≥94cm Females: ≥80cm | Males: ≥102cm Females: ≥88cm |

| Fasting blood glucose | ≥110mg/dl (≥6.1mmol/l) | ≥100mg/dl (≥5.6mmol/l) or previous diagnosis of type 2 diabetes | ≥100mg/dl (≥5.6mmol/l) or lipid-lowering treatment |

| Triglycerides | ≥150mg/dl (≥1.7mmol/l) | ≥150mg/dl (≥1.7mmol/l) or specific treatment | |

| HDL Cholesterol | Males: <40mg/dl (<1.03mmol/l) Females: <50mg/dl (<1.29mmol/l) | Males: <40mg/dl (<1.03mmol/l) Females: <50mg/dl (<1.29mmol/l) or specific treatment | |

| Blood pressure | Systolic ≥130mmHg or diastolic ≥ 85mmHg | Systolic ≥130mmHg or diastolic ≥85mmHg or anti-hypertensive treatment | |

IDF: International Diabetes Federation; NCEP-ATPIII: National Cholesterol Education Program-Adult Treatment Panel III; NHLBI/AHA: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association.

Morbid MetSyn: MetSyn with DM or CVD.

Premorbid MetSyn: MetSyn without DM or CVD.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (ICPC-2: R95. ICD-9: 491.2; 492; 496): Criteria of the GOLD guidelines.26

Urinary albumin excretion and albumin/creatinine ratio (ICPC-2: U90; U98. ICD-9: 593.6; 791): Criteria of the KDIGO guidelines.27

Albuminuria: albumin/creatinine ratio ≥30mg/g.

Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR): The following Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology collaboration (CKD-EPI)28 equations were used, expressed in ml/min/1.73 m2: Females with creatinine ≤0.7mg/dl=144×(creatinine)−0.329×(0.993)age; females with creatinine>0.7mg/dl=144×(creatinine)−1.209×(0.993)age; males with creatinine ≤0.9mg/dl=141×(creatinine)−0.411×(0.993)age; males with creatinine>0.9mg/dl=141×(creatinine)−1.209×(0.993)age.

CKD (ICPC-2: U99. ICD-9: 585): eGFR<60ml/min/1.73m2 or albumin/creatinine ratio ≥30mg/g (KDIGO).27

Erectile dysfunction: Inability to get and maintain an erection that is sufficient for satisfactory sexual intercourse.29

CVRF: Risk factor that predicts the likelihood of developing a CVD: Age (>55 in males;>65 in females), hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, smoking.

Very high CVRF: Marked hypercholesterolaemia or marked hypertension.

CVR modifier: Factor with possible potential for CVR reclassification when the SCORE (systematic coronary risk evaluation)2 score is close to the decision threshold. Lack of physical exercise, a history of premature CVD (males<55 or females<65) in a first-degree relative, low HDL-C, obesity.

CVR: Risk of death due to cardiovascular disease at 10 years. For the population aged 40 to 65, the CVR categories were assigned using the SCORE system2 for low-risk European countries. Low CVR: Population aged<40 without two or more CVRF; SCORE=0%. Moderate CVR: Population aged<40 with two or more CVRF; DM<40; MetSyn; SCORE 1–4%. High CVR: Very high CVRF; DM without CVRF; moderate CKD (eGFR 30–59ml/min/1.73m2); SCORE 5–9%. Very high CVR: Clinical CVD or CVD documented by imaging; DM with target organ damage or with CVRF; severe CKD (eGFR<30ml/min/1.73m2); SCORE ≥10%. Extreme CVR4: CVD associated with DM or CKD. The assigning of CVR in the population aged>65 was determined with the SCORE OP criteria.30

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences program (IBM® SPSS® Statistical release 20.0, Armonk, NY, United States). We determined the range, median and interquartile range (IQR) (25th percentile, 75th percentile) of the age variable. The mean and the standard deviation (±SD) were determined for the descriptive statistical analysis. Quantitative variables were compared using the two-tailed Levene's and Student's t tests for two variables or the one-way ANOVA for more than two variables. The variables analysed had normal distribution (skewness and kurtosis between −2 and +2). The qualitative variables were analysed by prevalence rates and percentages in each category, presented with lower and upper limits of the 95% confidence interval (CI). The inferential analysis of the qualitative data was performed with the Chi-square test, and of the quantitative data with Fisher's test. The odds ratios were determined with a 95% CI. All tests were considered statistically significant if the odds ratio estimates were greater than 1 or the 2-tail p value was less than 0.05. The prevalence rates were determined as gross rates and adjusted for age and gender. The adjustment of rates was carried out using the direct method31 using as standard populations the distributions by five-year and ten-year age brackets of the male and female populations of Madrid Region and Spain; information obtained from the database of the Instituto Nacional de Estadística32 [Spanish National Institute of Statistics] in January 2015.

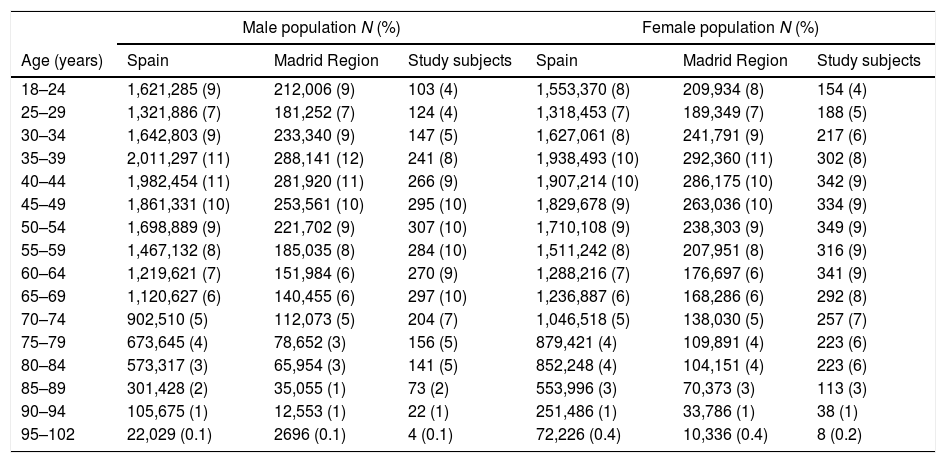

ResultsThe population aged over 18 of the Madrid Region and Spain was 5,196,828 and 38,102,546, respectively. The distribution by five-year age segments of the study and reference populations are shown in Table 2. The distribution of the ethnic origin of the inhabitants of the Madrid Region was as follows32: Spanish (88.9%); other European (4.9%); Central and South American (3.4%); North American (0.2%); African (1.5%); Asian (1.1%); and Oceanian (0.01%).

Age distribution of the study and reference populations.

| Male population N (%) | Female population N (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Spain | Madrid Region | Study subjects | Spain | Madrid Region | Study subjects |

| 18–24 | 1,621,285 (9) | 212,006 (9) | 103 (4) | 1,553,370 (8) | 209,934 (8) | 154 (4) |

| 25–29 | 1,321,886 (7) | 181,252 (7) | 124 (4) | 1,318,453 (7) | 189,349 (7) | 188 (5) |

| 30–34 | 1,642,803 (9) | 233,340 (9) | 147 (5) | 1,627,061 (8) | 241,791 (9) | 217 (6) |

| 35–39 | 2,011,297 (11) | 288,141 (12) | 241 (8) | 1,938,493 (10) | 292,360 (11) | 302 (8) |

| 40–44 | 1,982,454 (11) | 281,920 (11) | 266 (9) | 1,907,214 (10) | 286,175 (10) | 342 (9) |

| 45–49 | 1,861,331 (10) | 253,561 (10) | 295 (10) | 1,829,678 (9) | 263,036 (10) | 334 (9) |

| 50–54 | 1,698,889 (9) | 221,702 (9) | 307 (10) | 1,710,108 (9) | 238,303 (9) | 349 (9) |

| 55–59 | 1,467,132 (8) | 185,035 (8) | 284 (10) | 1,511,242 (8) | 207,951 (8) | 316 (9) |

| 60–64 | 1,219,621 (7) | 151,984 (6) | 270 (9) | 1,288,216 (7) | 176,697 (6) | 341 (9) |

| 65–69 | 1,120,627 (6) | 140,455 (6) | 297 (10) | 1,236,887 (6) | 168,286 (6) | 292 (8) |

| 70–74 | 902,510 (5) | 112,073 (5) | 204 (7) | 1,046,518 (5) | 138,030 (5) | 257 (7) |

| 75–79 | 673,645 (4) | 78,652 (3) | 156 (5) | 879,421 (4) | 109,891 (4) | 223 (6) |

| 80–84 | 573,317 (3) | 65,954 (3) | 141 (5) | 852,248 (4) | 104,151 (4) | 223 (6) |

| 85–89 | 301,428 (2) | 35,055 (1) | 73 (2) | 553,996 (3) | 70,373 (3) | 113 (3) |

| 90–94 | 105,675 (1) | 12,553 (1) | 22 (1) | 251,486 (1) | 33,786 (1) | 38 (1) |

| 95–102 | 22,029 (0.1) | 2696 (0.1) | 4 (0.1) | 72,226 (0.4) | 10,336 (0.4) | 8 (0.2) |

N: population sizes; (%): percentage of the total.

Of the initial sample, 7.6% refused to take part in the study or did not sign the informed consent form, 13.8% of the subjects had personal data errors or could not be contacted after an active search, and 4.7% met exclusion criteria. We also excluded 7.1% of the study subjects for whom there was no clinical data or whose medical records lacked relevant clinical information. The response rate was 74%. Losses, dropouts or study subjects who did not attend the clinical interview amounted to 4.2% (Fig. 1).

The study population consisted of 6631 subjects, 44.25% of them male (CI: 43.05; 45.45) (Table 1). The mean age (±SD) of the study population was 55.03 (±17.54 years), the median age was 54.56, and the range (IQR) was from 18.01 to 102.80 (41.55, 67.98).

The mean age (±SD) of the male population was 55.06 (±16.90 years), the median was 54.75, and the range (IQR) from 18.01 to 102.12 (42.01; 67.35). The mean age (±SD) of the female population was 55.01 (±18.04 years), the median was 54.36, and the range (IQR) from 18.01 to 102.80 (40.94; 68.77). The difference in the mean ages (0.05 [CI: −0.80, 0.90] years) between the male and female populations was not significant (p=0.908).

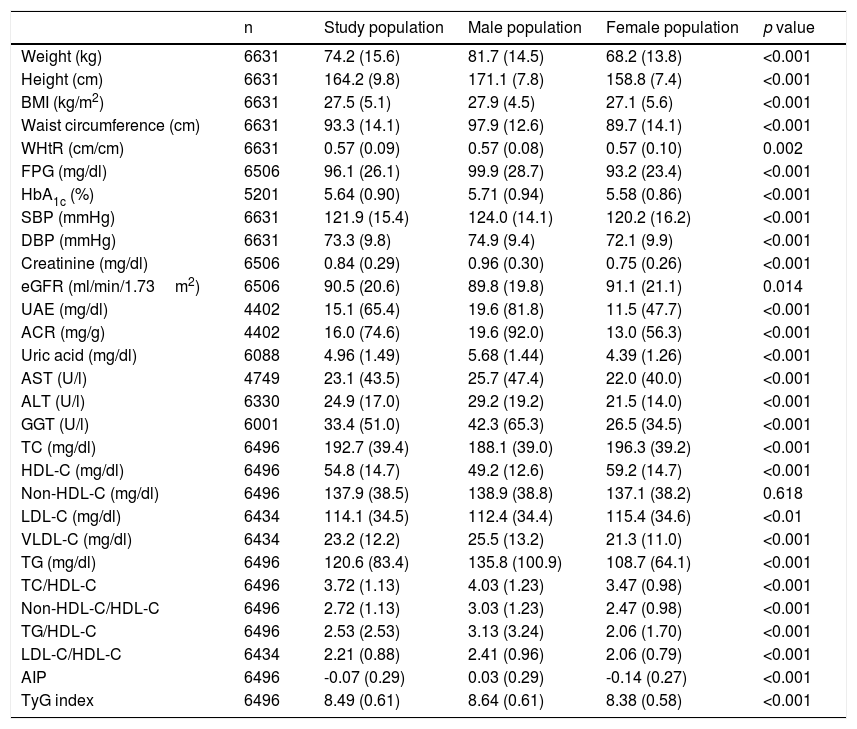

The means (±SD) of the anthropometric, blood pressure and biochemical variables of the study population and the significance of the differences between the male and female populations are shown in Table 3. The means of the highest parameters were: overweight (BMI: 27.5kg/m2), waist circumference (97.9cm in men and 89.7cm in women), WHtR (0.57), and HbA1c (5.6%). All the parameters mentioned were significantly higher in the male population, except for eGFR, TC, LDL-C and HDL-C, which were significantly higher in the female population.

Quantitative characteristicsa of the study population.

| n | Study population | Male population | Female population | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | 6631 | 74.2 (15.6) | 81.7 (14.5) | 68.2 (13.8) | <0.001 |

| Height (cm) | 6631 | 164.2 (9.8) | 171.1 (7.8) | 158.8 (7.4) | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 6631 | 27.5 (5.1) | 27.9 (4.5) | 27.1 (5.6) | <0.001 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 6631 | 93.3 (14.1) | 97.9 (12.6) | 89.7 (14.1) | <0.001 |

| WHtR (cm/cm) | 6631 | 0.57 (0.09) | 0.57 (0.08) | 0.57 (0.10) | 0.002 |

| FPG (mg/dl) | 6506 | 96.1 (26.1) | 99.9 (28.7) | 93.2 (23.4) | <0.001 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5201 | 5.64 (0.90) | 5.71 (0.94) | 5.58 (0.86) | <0.001 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 6631 | 121.9 (15.4) | 124.0 (14.1) | 120.2 (16.2) | <0.001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 6631 | 73.3 (9.8) | 74.9 (9.4) | 72.1 (9.9) | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 6506 | 0.84 (0.29) | 0.96 (0.30) | 0.75 (0.26) | <0.001 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73m2) | 6506 | 90.5 (20.6) | 89.8 (19.8) | 91.1 (21.1) | 0.014 |

| UAE (mg/dl) | 4402 | 15.1 (65.4) | 19.6 (81.8) | 11.5 (47.7) | <0.001 |

| ACR (mg/g) | 4402 | 16.0 (74.6) | 19.6 (92.0) | 13.0 (56.3) | <0.001 |

| Uric acid (mg/dl) | 6088 | 4.96 (1.49) | 5.68 (1.44) | 4.39 (1.26) | <0.001 |

| AST (U/l) | 4749 | 23.1 (43.5) | 25.7 (47.4) | 22.0 (40.0) | <0.001 |

| ALT (U/l) | 6330 | 24.9 (17.0) | 29.2 (19.2) | 21.5 (14.0) | <0.001 |

| GGT (U/l) | 6001 | 33.4 (51.0) | 42.3 (65.3) | 26.5 (34.5) | <0.001 |

| TC (mg/dl) | 6496 | 192.7 (39.4) | 188.1 (39.0) | 196.3 (39.2) | <0.001 |

| HDL-C (mg/dl) | 6496 | 54.8 (14.7) | 49.2 (12.6) | 59.2 (14.7) | <0.001 |

| Non-HDL-C (mg/dl) | 6496 | 137.9 (38.5) | 138.9 (38.8) | 137.1 (38.2) | 0.618 |

| LDL-C (mg/dl) | 6434 | 114.1 (34.5) | 112.4 (34.4) | 115.4 (34.6) | <0.01 |

| VLDL-C (mg/dl) | 6434 | 23.2 (12.2) | 25.5 (13.2) | 21.3 (11.0) | <0.001 |

| TG (mg/dl) | 6496 | 120.6 (83.4) | 135.8 (100.9) | 108.7 (64.1) | <0.001 |

| TC/HDL-C | 6496 | 3.72 (1.13) | 4.03 (1.23) | 3.47 (0.98) | <0.001 |

| Non-HDL-C/HDL-C | 6496 | 2.72 (1.13) | 3.03 (1.23) | 2.47 (0.98) | <0.001 |

| TG/HDL-C | 6496 | 2.53 (2.53) | 3.13 (3.24) | 2.06 (1.70) | <0.001 |

| LDL-C/HDL-C | 6434 | 2.21 (0.88) | 2.41 (0.96) | 2.06 (0.79) | <0.001 |

| AIP | 6496 | -0.07 (0.29) | 0.03 (0.29) | -0.14 (0.27) | <0.001 |

| TyG index | 6496 | 8.49 (0.61) | 8.64 (0.61) | 8.38 (0.58) | <0.001 |

ACR: albumin/creatinine ratio; AIP: atherogenic index of plasma; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; BMI: body mass index (weight/height2); DBP: diastolic blood pressure; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate according to CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration); FPG: fasting plasma glucose; GGT: gamma-glutamyl transferase; HbA1c: glycosylated haemoglobin A1c; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; n: number of cases; p value: of the difference in means between the male and female populations; SBP: systolic blood pressure; TC: total blood cholesterol; TG: blood triglycerides; TyG: TG and glucose index; UAE: urinary albumin excretion; VLDL-C: very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; WHtR: waist-to-height ratio.

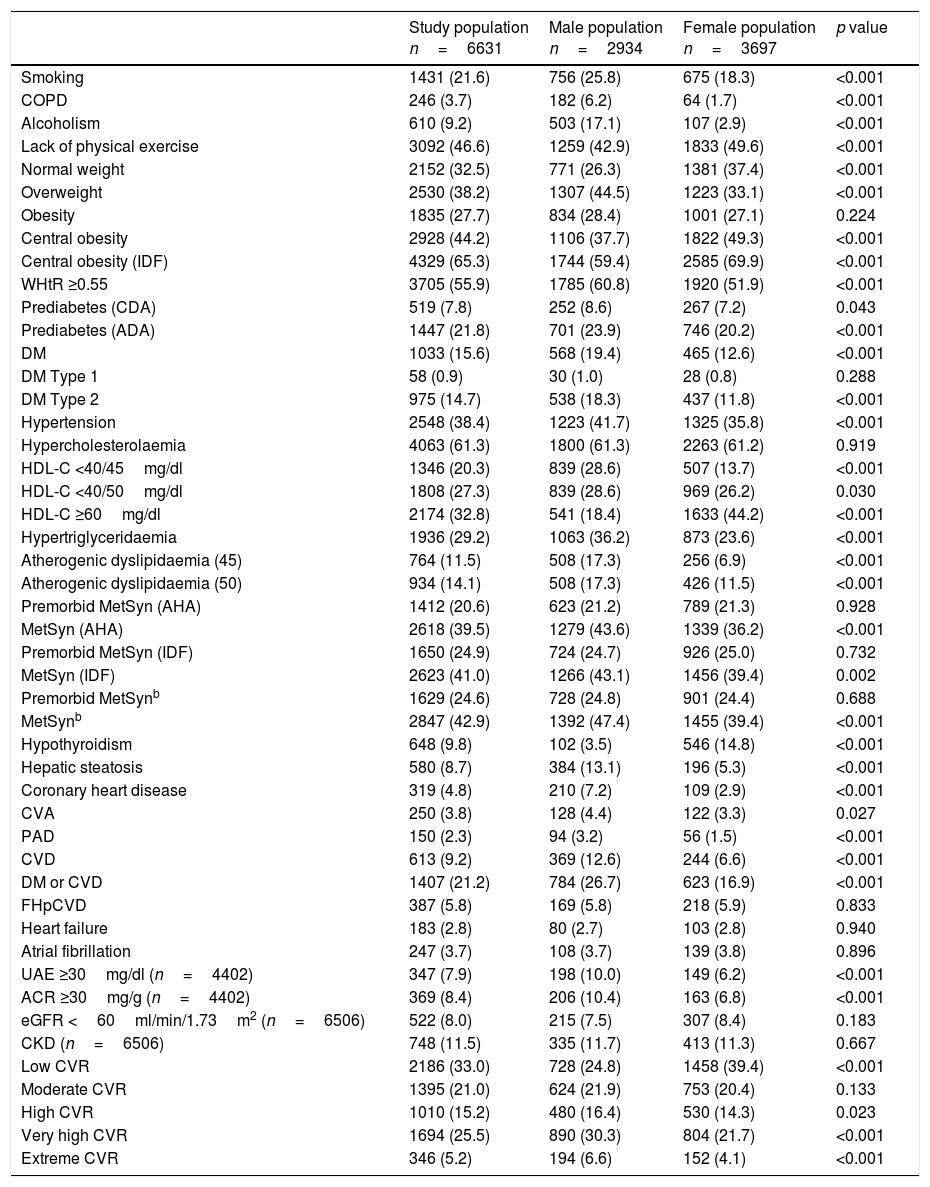

The crude prevalence rates of the qualitative characteristics and morbidity of the study population and the significance of the differences between the male and female populations are shown in Table 4. The highest overall crude prevalence rates were: smoking (22%); physical inactivity (47%); overweight (38%); obesity (28%); abdominal obesity (65%); WHtR ≥0.55 (56%); prediabetes (22%); DM (16%); hypertension (38%); hypercholesterolaemia (61%); HTG (29%); atherogenic dyslipidaemia (14%); MetSyn (43%); and premorbid MetSyn (25%). There were no differences in crude prevalence rates between male and female populations in the following CVRF and disorders: history of premature CVD in first-degree relative; obesity; type 1 DM; hypercholesterolaemia; premorbid MetSyn; heart failure; atrial fibrillation; and CKD. The rest of the crude prevalence rates were significantly higher in the male population, except for physical inactivity, abdominal obesity, hypothyroidism and HDL-C ≥60mg/dl, which were significantly higher in the female population.

Qualitative characteristicsa of the study population.

| Study population n=6631 | Male population n=2934 | Female population n=3697 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking | 1431 (21.6) | 756 (25.8) | 675 (18.3) | <0.001 |

| COPD | 246 (3.7) | 182 (6.2) | 64 (1.7) | <0.001 |

| Alcoholism | 610 (9.2) | 503 (17.1) | 107 (2.9) | <0.001 |

| Lack of physical exercise | 3092 (46.6) | 1259 (42.9) | 1833 (49.6) | <0.001 |

| Normal weight | 2152 (32.5) | 771 (26.3) | 1381 (37.4) | <0.001 |

| Overweight | 2530 (38.2) | 1307 (44.5) | 1223 (33.1) | <0.001 |

| Obesity | 1835 (27.7) | 834 (28.4) | 1001 (27.1) | 0.224 |

| Central obesity | 2928 (44.2) | 1106 (37.7) | 1822 (49.3) | <0.001 |

| Central obesity (IDF) | 4329 (65.3) | 1744 (59.4) | 2585 (69.9) | <0.001 |

| WHtR ≥0.55 | 3705 (55.9) | 1785 (60.8) | 1920 (51.9) | <0.001 |

| Prediabetes (CDA) | 519 (7.8) | 252 (8.6) | 267 (7.2) | 0.043 |

| Prediabetes (ADA) | 1447 (21.8) | 701 (23.9) | 746 (20.2) | <0.001 |

| DM | 1033 (15.6) | 568 (19.4) | 465 (12.6) | <0.001 |

| DM Type 1 | 58 (0.9) | 30 (1.0) | 28 (0.8) | 0.288 |

| DM Type 2 | 975 (14.7) | 538 (18.3) | 437 (11.8) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 2548 (38.4) | 1223 (41.7) | 1325 (35.8) | <0.001 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 4063 (61.3) | 1800 (61.3) | 2263 (61.2) | 0.919 |

| HDL-C <40/45mg/dl | 1346 (20.3) | 839 (28.6) | 507 (13.7) | <0.001 |

| HDL-C <40/50mg/dl | 1808 (27.3) | 839 (28.6) | 969 (26.2) | 0.030 |

| HDL-C ≥60mg/dl | 2174 (32.8) | 541 (18.4) | 1633 (44.2) | <0.001 |

| Hypertriglyceridaemia | 1936 (29.2) | 1063 (36.2) | 873 (23.6) | <0.001 |

| Atherogenic dyslipidaemia (45) | 764 (11.5) | 508 (17.3) | 256 (6.9) | <0.001 |

| Atherogenic dyslipidaemia (50) | 934 (14.1) | 508 (17.3) | 426 (11.5) | <0.001 |

| Premorbid MetSyn (AHA) | 1412 (20.6) | 623 (21.2) | 789 (21.3) | 0.928 |

| MetSyn (AHA) | 2618 (39.5) | 1279 (43.6) | 1339 (36.2) | <0.001 |

| Premorbid MetSyn (IDF) | 1650 (24.9) | 724 (24.7) | 926 (25.0) | 0.732 |

| MetSyn (IDF) | 2623 (41.0) | 1266 (43.1) | 1456 (39.4) | 0.002 |

| Premorbid MetSynb | 1629 (24.6) | 728 (24.8) | 901 (24.4) | 0.688 |

| MetSynb | 2847 (42.9) | 1392 (47.4) | 1455 (39.4) | <0.001 |

| Hypothyroidism | 648 (9.8) | 102 (3.5) | 546 (14.8) | <0.001 |

| Hepatic steatosis | 580 (8.7) | 384 (13.1) | 196 (5.3) | <0.001 |

| Coronary heart disease | 319 (4.8) | 210 (7.2) | 109 (2.9) | <0.001 |

| CVA | 250 (3.8) | 128 (4.4) | 122 (3.3) | 0.027 |

| PAD | 150 (2.3) | 94 (3.2) | 56 (1.5) | <0.001 |

| CVD | 613 (9.2) | 369 (12.6) | 244 (6.6) | <0.001 |

| DM or CVD | 1407 (21.2) | 784 (26.7) | 623 (16.9) | <0.001 |

| FHpCVD | 387 (5.8) | 169 (5.8) | 218 (5.9) | 0.833 |

| Heart failure | 183 (2.8) | 80 (2.7) | 103 (2.8) | 0.940 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 247 (3.7) | 108 (3.7) | 139 (3.8) | 0.896 |

| UAE ≥30mg/dl (n=4402) | 347 (7.9) | 198 (10.0) | 149 (6.2) | <0.001 |

| ACR ≥30mg/g (n=4402) | 369 (8.4) | 206 (10.4) | 163 (6.8) | <0.001 |

| eGFR <60ml/min/1.73m2 (n=6506) | 522 (8.0) | 215 (7.5) | 307 (8.4) | 0.183 |

| CKD (n=6506) | 748 (11.5) | 335 (11.7) | 413 (11.3) | 0.667 |

| Low CVR | 2186 (33.0) | 728 (24.8) | 1458 (39.4) | <0.001 |

| Moderate CVR | 1395 (21.0) | 624 (21.9) | 753 (20.4) | 0.133 |

| High CVR | 1010 (15.2) | 480 (16.4) | 530 (14.3) | 0.023 |

| Very high CVR | 1694 (25.5) | 890 (30.3) | 804 (21.7) | <0.001 |

| Extreme CVR | 346 (5.2) | 194 (6.6) | 152 (4.1) | <0.001 |

ACR: albumin-creatinine ratio; ADA: American Diabetes Association; AHA: American Heart Association; ATPIII: Adult Treatment Panel III; BMI: body mass index (weight/height2); CDA: Canadian Diabetes Association; CKD: chronic kidney disease; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVA: cerebrovascular accident or stroke; CVD: cardiovascular disease; CVR: cardiovascular risk; DM: diabetes mellitus; eGFR: glomerular filtration rate estimated according to CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology collaboration); FHpCVD: Family history of premature CVD (in a first-degree relative); HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; IDF: International Diabetes Federation; MetSyn: metabolic syndrome; NCEP-ATPIII: National Cholesterol Education Program-Adult Treatment Panel III; NHLBI: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; p value: of the difference in means between the male and female populations; PAD: peripheral arterial disease; UAE: urinary albumin excretion; WHtR: waist-to-height ratio.

Normal weight24: BMI from 18.5 to 24.9kg/m2. Overweight24: BMI from 25.0 to 29.9kg/m2. Obesity24: BMI ≥30kg/m2. Central obesity13: Waist circumference ≥102cm (males) or ≥88cm (females). Central obesity (IDF)12: ≥94cm (males) or ≥80cm (females). Prediabetes (CDA)19: blood glucose from 110 to 125mg/dl, or HbA1c from 6% to 6.4%. Prediabetes (ADA)18: blood glucose from 100 to 125mg/dl, or HbA1c from 5.7% to 6.4%. HDL-C<40/45: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol<40mg/dl (males) or<45mg/dl (females). HDL-C<40/50: idem<50mg/dl (females). Atherogenic dyslipidaemia (45): hypertriglyceridaemia and HDL-C<45mg/dl (females). Atherogenic dyslipidaemia (50): hypertriglyceridaemia and HDL-C<50mg/dl (females). MetSyn (AHA)10,11: metabolic syndrome according to NCEP-ATPIII/NHLBI/AHA. MetSyn (IDF)12: Metabolic syndrome according to IDF. eGFR: glomerular filtration rate estimated according to CKD-EPI.28

CVD caused 119,778 deaths in 2016 and was the leading cause of death (30%) in the Spanish population.33 Cardiovascular mortality has been reduced in recent years thanks to intervention on CVRF such as smoking, hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia. However, the intervention has not had such positive effects34 on eating habits, physical inactivity, obesity and DM. The preliminary information provided in this article describes the epidemiological situation of a population with a sustained high prevalence of lifestyle-related CVRF and metabolism-related morbidity. The study population had quantitative anthropometric and metabolic characteristics that predispose to the diagnosis of MetSyn. The mean BMI indicated grade ii overweight or obesity; waist circumferences exceeded the limits established by the IDF,12 and the HbA1c was on the border of the lower limit for prediabetes according to the IDF.12 However, the population averages showed good control of blood pressure, eGFR, FPG and lipid profile.

The highest overall crude prevalence rates were cardiometabolic CVRF: smoking, physical inactivity, overweight, obesity, abdominal obesity, increased WHtR, prediabetes, DM, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, HTG, atherogenic dyslipidaemia, MetSyn and premorbid MetSyn. The high prevalence of cardiometabolic CVRF suggests that 21% of the population could go on to suffer from CVD or DM, with 31% having very high or extreme CVR.

However, to assess the true epidemiological magnitude and to compare prevalence rates between different populations, it is important to bear in mind that both age and gender are factors directly related to CVRF, CVD and cardiometabolic morbidity. We therefore need to analyse not only the crude prevalence rates, but also the specific prevalence rates stratified by age groups, and the overall prevalence rates adjusted for age and gender.

In Spain, there are large regional differences in both the prevalence and the degree of control of CVRF.35 Population prevention strategies have been shown to be highly beneficial,1 and it is therefore essential to make a population health diagnosis that includes all the factors related to cardiovascular pathology.

The aim of the SIMETAP study was to provide an update on the epidemiological dimension of CVRF, CVD, MetSyn and associated metabolic morbidity. Our intention was that this update should facilitate comparison between different populations, stimulate health intervention and encourage health authorities to intensify population prevention strategies by more efficiently applying available resources. This article is the preamble to further more detailed analyses of prevalence rates both by stratified age groups and adjusted for age and gender with reference populations from the Madrid Region and from Spain.

ConclusionsThis study found population averages of good control of blood pressure, eGFR, FPG and lipid profile. However, the anthropometric characteristics of the population, which are overweight, central obesity (according to IDF criteria), and a mean HbA1c of 5.6%, suggest a tendency towards the diagnosis of prediabetes or MetSyn.

The highest overall crude prevalence rates were recorded in inadequate lifestyles (smoking, physical inactivity, obesity) and cardiometabolic morbidity (prediabetes, DM, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and MetSyn). This could signify that a large percentage of the population has high or very high CVR.

To determine the true epidemiological dimension and be able to compare populations, we need to analyse prevalence rates stratified by age groups and adjusted for age and gender.

FundingThe Agencia “Pedro Laín Entralgo” de Formación, Investigación y Estudios Sanitarios [“Pedro Laín Entralgo” Agency for Training, Research and Health Studies] for the Madrid Region (grant No. RS05/2010) provided funding for conducting this study. The Research Commission of the Madrid Region Primary Care Management Department for Planning and Quality issued a favourable opinion for the study to be conducted.

Conflicts of interestFor this study, the authors declare that there was no interference in the attaining or interpretation of the results and that they therefore have no conflicts of interest.

We would like to thank the following physicians who have participated in the SIMETAP Study Research Group for their assistance and collaboration:

Abad Schilling C., Adrián Sanz M., Aguilera Reija P., Alcaraz Bethencourt A., Alonso Roca R., Álvarez Benedicto R., Arranz Martínez E., Arribas Álvaro P., Baltuille Aller M.C., Barrios Rueda E., Benito Alonso E., Berbil Bautista M.L., Blanco Canseco J.M., Caballero Ramírez N., Cabello Igual P., Cabrera Vélez R., Calderín Morales M.P., Capitán Caldas M., Casaseca Calvo T.F., Cique Herráinz J.A., Ciria de Pablo C., Chao Escuer P., Dávila Blázquez G., de la Peña Antón N., de Prado Prieto L., del Villar Redondo M.J., Delgado Rodríguez S., Díez Pérez M.C., Durán Tejada M.R., Escamilla Guijarro N., Escrivá Ferrairó R.A., Fernández Vicente T., Fernández-Pacheco Vila D., Frías Vargas M.J., García Álvarez J.C., García Fernández M.E., García García Alcañiz M.P., García Granado M.D., García Pliego R.A., García Redondo M.R., García Villasur M.P., Gómez Díaz E., Gómez Fernández O., González Escobar P., González-Posada Delgado J.A., Gutiérrez Sánchez I. Hernández Beltrán M.I., Hernández de Luna M.C., Hernández López R.M., Hidalgo Calleja Y., Holgado Catalán M.S., Hombrados Gonzalo M.P., Hueso Quesada R., Ibarra Sánchez A.M., Iglesias Quintana J.R., Íscar Valenzuela I., Iturmendi Martínez N., Javierre Miranda A.P., López Uriarte B., Lorenzo Borda M.S., Luna Ramírez S., Macho del Barrio A.I., Magán Tapia P., Marañón Henrich N., Mariño Suárez J.E., Martín Calle M.C., Martín Fernández A.I., Martínez Cid de Rivera E., Martínez Irazusta J., Migueláñez Valero A., Minguela Puras M.E., Montero Costa A., Mora Casado C., Morales Cobos L.E., Morales Chico M.R., Moreno Fernández J.C., Moreno Muñoz M.S., Palacios Martínez D., Pascual Val T., Pérez Fernández M., Pérez Muñoz R., Plata Barajas M.T., Pleite Raposo R., Prieto Marcos M., Quintana Gómez J.L., Redondo de Pedro S., Redondo Sánchez M., Reguillo Díaz J., Remón Pérez B., Revilla Pascual E., Rey López A.M., Ribot Catalá C., Rico Pérez M.R., Rivera Teijido M., Rodríguez Cabanillas R., Rodríguez de Cossío A., Rodríguez de Mingo E., Rodríguez Rodríguez A.O., Rosillo González A., Rubio Villar M., Ruiz Díaz L., Ruiz García A., Sánchez Calso A., Sánchez Herráiz M., Sánchez Ramos M.C., Sanchidrián Fernández P.L., Sandín de Vega E., Sanz Pozo B., Sanz Velasco C., Sarriá Sánchez M.T., Simonaggio Stancampiano P., Tello Meco I., Vargas-Machuca Cabañero C., Velazco Zumarrán J.L., Vieira Pascual M.C., Zafra Urango C., Zamora Gómez M.M., Zarzuelo Martín N.

Please cite this article as: Ruiz-García A, Arranz-Martínez E, García-Álvarez JC, Morales-Cobos LE, García-Fernández ME, de la Peña-Antón N, et al. Población y metodología del estudio SIMETAP: Prevalencia de factores de riesgo cardiovascular, enfermedades cardiovasculares y enfermedades metabólicas relacionadas. Clin Investig Arterioscler. 2018;30:197–208.