The development of cardiovascular disease (CVD) appears in subjects with several cardiovascular risk factors (CVRF). However, other agents could be related to the appearance of CVD, like chemotherapy drugs. We present a 63 years-old man with very high cardiovascular risk (CVR) and chronic myeloid leukemia under treatment with nilotinib. Despite a good control of cardiovascular risk factors, he development a severe and acceleratted peripherical arterial disease (PAD). PAD occurs in 5–20% patients under treatment with nilotinib and it is more frecuently in subjects with several CVRF.

El desarrollo de enfermedad cardiovascular (ECV) suele presentarse en sujetos con varios factores de riesgo cardiovascular (FRCV). Sin embargo, existen otros condicionantes que pueden estar relacionados con la aparición de ECV, como pueden ser los fármacos antineoplásicos. Presentamos en caso de un varón de 63 años con muy alto riesgo cardiovascular (RCV), con antecedente personal de leucemia mieloide crónica (LMC) en tratamiento con nilotinib que, a pesar de buen control metabólico, desarrolló una enfermedad arterial periférica (EAP) grave y acelerada. La EAP se ha descrito en el 5-20% de los pacientes bajo tratamiento con nilotinib, siendo más frecuentes en los sujetos con varios FRCV.

The development of cardiac disease, ischemic ictus and peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is usually associated with the presence of several cardiovascular risk factors (CVRF). Nevertheless, other factors may also cause cardiovascular disease (CVD). Among others, some drugs used to treat neoplastic diseases increase the incidence of CVRF and CVD, so that they too must be taken into account as possible etiopathogenic agents.

Clinical caseWe present the case of a male with a history of arterial hypertension, type II diabetes mellitus and hypercholesterolemia. He had never smoked. In treatment with metformin, candesartan and atorvastatin, with which he was within target values for his CVRF. In July 2011, at 63 years old, he was diagnosed with chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML). He started treatment with nilotinib 300 mg every 12 h, achieving a molecular response and complete cytogenetic remission.

In March 2013 he was hospitalised due to acute coronary syndrome without elevation of the ST segment (CSWOEST). Coronography showed severe stenosis of the anterior descending and right coronary arteries. Two pharmoactive stents had to be placed in the anterior descending artery and one was placed in the right coronary artery.

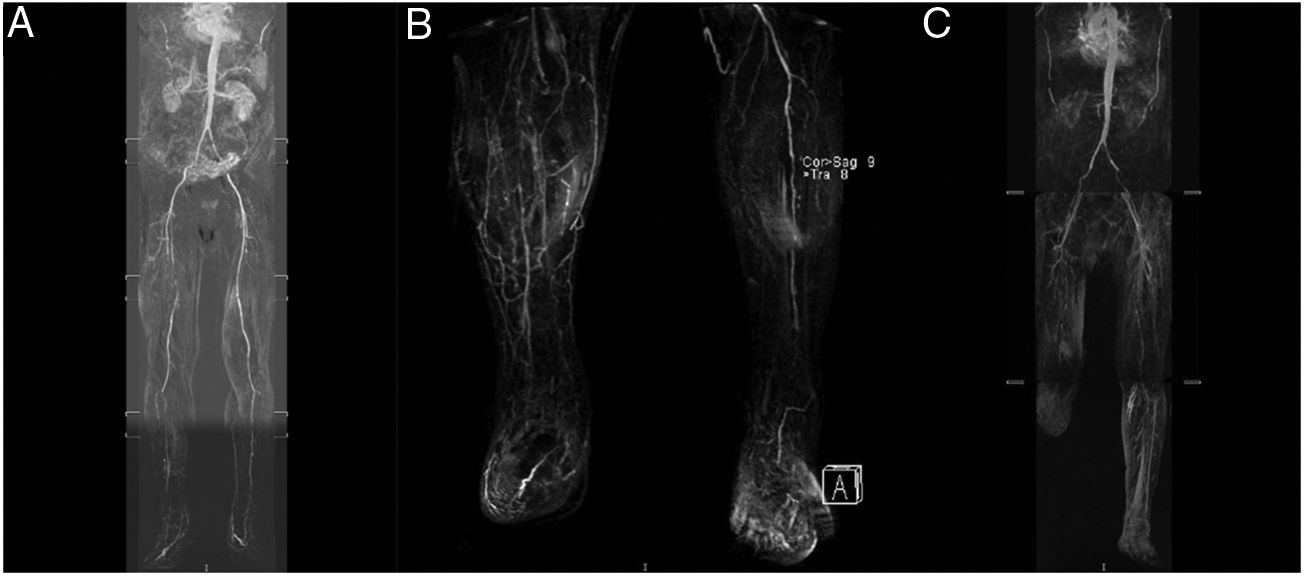

During the following year, in spite of good control of the CVRF (HbA1c <6.5 mg/dL, cLDL <70 mg/dL and arterial pressure <140/90 mmHg) and the double anti-aggregant treatment, the patient developed symptoms of intermittent claudication of the right lower limb (RLL) with accelerated evolution, pain when resting and incipient cutaneous lesions with a vascular origin. Angio magnetic resonance angiography (Fig. 1A) showed important RLL arterial involvement, without vascular involvement of the left lower limb (LLL). In January 2015 angioplasty of the right superficial femoral and peroneal arteries was performed, and a saphen patch was placed on the common femoral artery.

(A) August 2014: significant involvement of the femoral surface and tibial-peroneal territory of the RLL. (B) November 2015: RLL with permeable popliteal artery and complete occlusion of the tibial-peroneal trunk and anterior tibial artery; LLL with occlusion of the superficial femoral artery in its proximal and medial part, with distal reinjection. Popliteal artery permeable throughout its length. Proximal occlusion of the anterior and posterior tibial artery. Occlusion of the proximal third of the peroneal artery and permeability of the posterior tibial artery. (C) February 2016: LLL with severe atheromatous lesions producing critical stenosis in the origin of the common and right external iliac artery. Complete occlusion of the superficial femoral artery in the middle third of the thigh. RLL: right lower limb; LLL: left lower limb. gr1.

In the following months he was hospitalised again several times in Vascular Surgery due to new symptoms of ischemia when resting, in the RLL as well as the LLL. In March 2015 he required consecutive revascularisation of the LLL using a self-expanding stent at the level of the common iliac artery, the external iliac artery and the superficial femoral artery of the LLL, and re-intervention in the RLL due to repeat occlusion of the superficial femoral artery and the posterior tibial artery. In September 2015 he developed a new episode of ischemia in the RLL that required amputation of the 1st and 2nd toes. In November 2015, due to the persistence of the symptoms of ischemia and pain when resting, angio magnetic resonance imaging showed complete occlusion of the tibial-peroneal trunk and the anterior tibial artery (Fig. 1B), requiring amputation below the condyle of the RLL. In February 2016 he had repeat revascularisation of the LLL due to occlusive lesions (Fig. 1C). Finally, in April 2016 he was hospitalised again due to ischemia of the 1st toe, with torpid evolution in the ward which finally made amputation of the RLL necessary below the condyle.

DiscussionArteriosclerosis is a systemic disease that affect medium to large calibre arteries. Its manifestations may affect the whole circulatory system, causing ischemic cardiopathy, ictus or PAD, depending on the vascular region that is affected.

The main risk factors for the development of PAD are the same as those for the development of arteriosclerosis: age, male sex, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes and smoking. A family history of CVD, chronic kidney disease, chronic inflammatory conditions and hyperhomocysteinemia, etc. may also play an important role in the development of this disease.1 Moreover, the fundamental role of the adverse effects of medicaments must not be forgotten.

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) are the treatment for CML. They strongly inhibit the activity of the tyrosine kinase protein BCR-ABL which causes this disease. After the introduction of this therapy in 2001, the prognosis for the pathology changed radically. The average survival at 10 years was 10% prior to the TKI, and it is now similar to the survival rate of the general population. Nevertheless, the increase in the survival of patients with CML has led to an increase in the incidence of CVD. This incidence has been found to be higher in patients with CML who are being treated with TKI than it is in the population with CML without such treatment, or in the general population.2

Nilotinib is a second generation TKI that induces complete cytogenetic remission in a high proportion of patients with resistance to imatinib. However, it has been found to have direct proatherogenic and antiangiogenic effects on vascular endothelial cells, and these may contribute to the development of PAD in up to 5-20% of the patients treated.3,4 This effect arises due to increasing regulation of proatherogenic adhesion proteins (ICAM-1, E-selectin, VCAM-1), as well as suppressing angiogenesis and the proliferation of endothelial cells, mediating over the angiopoietin receptors 1, TEK, ABL-2, JAK-1 and MAP kinases. Additionally, it has also been found to increase the levels of glucose and LDL cholesterol. The probability of CVD increases with increasing doses of nilotinib.5

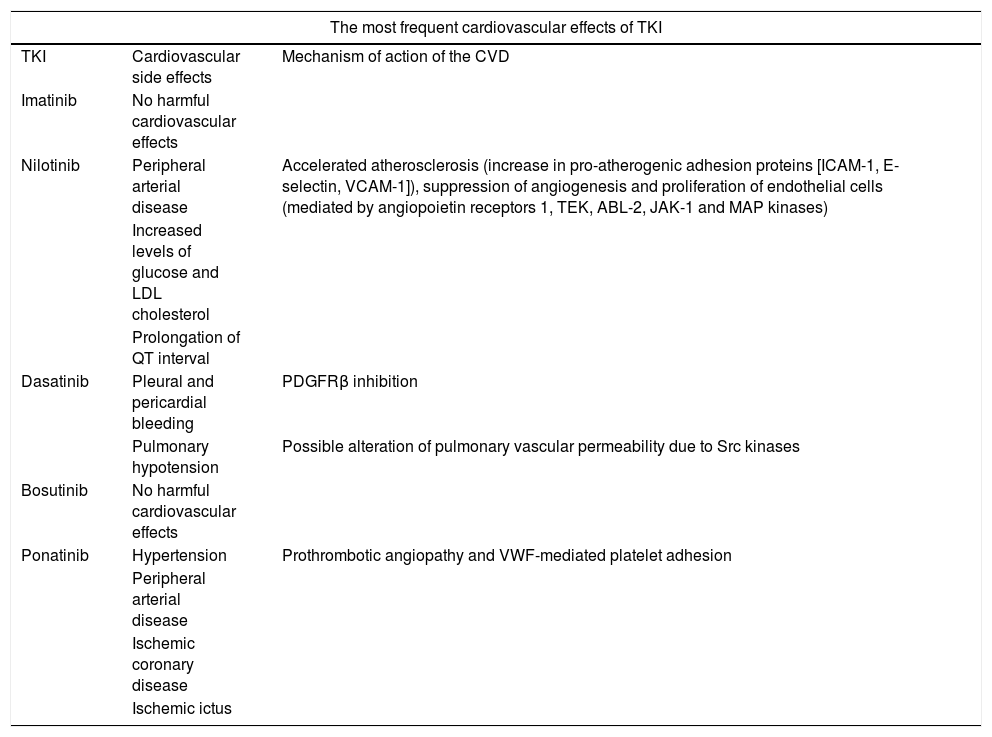

As may be seen in Table 1, nilotinib is not the only drug that produces side effects at a cardiovascular level, as measured by different biomarkers.6 It has been observed that the incidence of cardiovascular events in patients with CML during treatment with TKI is higher in patients with several previous CVRF.7

The most frequent cardiovascular effects of TKI.

| The most frequent cardiovascular effects of TKI | ||

|---|---|---|

| TKI | Cardiovascular side effects | Mechanism of action of the CVD |

| Imatinib | No harmful cardiovascular effects | |

| Nilotinib | Peripheral arterial disease | Accelerated atherosclerosis (increase in pro-atherogenic adhesion proteins [ICAM-1, E-selectin, VCAM-1]), suppression of angiogenesis and proliferation of endothelial cells (mediated by angiopoietin receptors 1, TEK, ABL-2, JAK-1 and MAP kinases) |

| Increased levels of glucose and LDL cholesterol | ||

| Prolongation of QT interval | ||

| Dasatinib | Pleural and pericardial bleeding | PDGFRβ inhibition |

| Pulmonary hypotension | Possible alteration of pulmonary vascular permeability due to Src kinases | |

| Bosutinib | No harmful cardiovascular effects | |

| Ponatinib | Hypertension | Prothrombotic angiopathy and VWF-mediated platelet adhesion |

| Peripheral arterial disease | ||

| Ischemic coronary disease | ||

| Ischemic ictus | ||

ABL-2: ABL proto-oncogen 2; CVD: cardiovascular disease; VWF: Von Willebrand factor; ICAM: intercellular adhesion molecule; TKI: tyrosin kinase inhibitor; JAK-1: Janus kinase-1; MAP kinases: mitogen activated protein-kinases; PDGFRβ: platelet derived growth factor beta receptor; TEK: TEK tyrosin kinase receptor; VCAM-1: vascular-1 cytoadhesion molecule.

In our case, although the patient had high cardiovascular risk at the moment of IAMSEST, it can be seen that in spite of good control of the CVRF he continued developing CVD, which was severe and swift to evolve. The TKI was only suspended after it was recognised as a possible etiopathogenic factor in the disease. We believe that the TKI contributed to the development of the PAD in the patient, given that his CVRF were controlled (although it is true that this does not imply the appearance of new events) and the episodes of ischemia did not return after its suspension (30 months free of disease). It is impossible to establish a causal relationship, as it would not be ethical to commence treatment with the drug again.

The TKI was recognised as a risk factor for CVD some time after they had started to be used to treat CML in 2001. It was only after the work of Aichberger et al.8 in 2011, which detected 3 individuals with rapidly progressing PAD in a series of 24 patients, that TKI started to be considered causes of CVD. Subsequently, numerous papers have confirmed the relationship between nilotinib (and other TKI) and the early onset of CVD.

It has now been observed that the only tool for the prediction of cardiovascular events in patients with CML treated using TKI is the calculation of cardiovascular risk.9 The complexity of these patients, characterised by the increase in their survival, increased the incidence of CVD and drugs with cardiovascular side effects, makes it necessary for them to be evaluated by multidisciplinary teams composed of cardiologists, internal medicine specialists and haematologists.

FinancingThe authors declare that they received no financing for this paper.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Roa-Chamorro R, Torres-Quintero L, García de los Ríos C, Manuel Puerta-Puerta J, González-Bustos P, Mediavilla-García JD. Enfermedad cardiovascular progresiva en paciente bajo tratamiento con nilotinib. Clin Investig Arterioscler. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arteri.2019.05.002