The therapeutic management of severe hypertriglyceridaemia represents a clinical challenge.

ObjectivesThe objectives of this study were (1) to identify the clinical characteristics of patients with severe hypertriglyceridaemia, and (2) to analyse the treatment established by the physicians in each case.

MethodsA cross-sectional study was carried out using the computerised medical records of all patients >18 years of age with a blood triglyceride level ≥1000mg/dL between 1 January 2011 and 31 December 2016. Clinical and laboratory variables were collected. The behaviour of the physicians in the 6 months after the lipid finding was analysed.

ResultsA total of 420 patients were included (mean age 49.1±11.4 years, males 78.8%). The median of triglycerides was 1329mg/dL (interquartile range 1174–1658). No secondary causes were found in 34.1% of the patients. The most frequent secondary causes were obesity (38.6%) and diabetes (28.1%). Physical activity was recommended and a nutritionist was referred to in 49.1% and 44.2% of the patients, respectively. Secondary causes were identified and attempts were made to correct them in 40.7% of cases. The most indicated pharmacological treatments were fenofibrate 200mg/day (26.5%) and gemfibrozil 900mg/day (19.3%). Few patients received the indication of omega 3 fatty acids or niacin.

ConclusionThis study showed, for the first time in our country, the characteristics of a population with severe hypertriglyceridaemia. The therapeutic measures instituted by the physicians were insufficient. Knowing the characteristics in this particular clinical scenario could improve the current approach of these patients.

El manejo terapéutico de la hipertrigliceridemia grave representa un desafío clínico.

Objetivos1) Identificar las características clínicas de los pacientes con hipertrigliceridemia grave; 2) Analizar el tratamiento instaurado por el médico en cada caso.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio de corte transversal a partir de la historia clínica electrónica. Se incluyeron todos los pacientes>18 años con una determinación en sangre de triglicéridos≥1.000mg/dL entre el 01/01/2011 y el 31/12/2016. Se identificaron variables clínicas y de laboratorio. Se analizó la conducta de los médicos tratantes en los 6 meses posteriores al hallazgo lipídico.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 420 pacientes (edad media 49,1±11,4 años, varones el 78,8%). La mediana de triglicéridos fue 1.329mg/dL (rango intercuartílico 1.174-1.658). En el 34,1% de los pacientes no se encontraron causas secundarias. Las causas secundarias más frecuentes fueron la obesidad (38,6%) y la diabetes (28,1%). Se recomendó realizar actividad física y se derivó a un nutricionista en el 49,1% y el 44,2% de los pacientes respectivamente. Las causas secundarias se identificaron y se intentaron corregir en el 40,7% de los casos. Los esquemas terapéuticos más indicados fueron fenofibrato 200mg/día (26,5%) y gemfibrozil 900mg/día (19,3%). Pocos pacientes recibieron la indicación de ácidos grasos omega 3 o niacina.

ConclusiónNuestro trabajo mostró por primera vez en nuestro país las características de una población con hipertrigliceridemia grave. Las medidas terapéuticas instauradas por los médicos fueron insuficientes. Conocer las características en este particular escenario clínico podría mejorar el abordaje actual de estos pacientes.

Therapeutic management of severe hypertriglyceridaemia is a clinical challenge. Hypertriglyceridaemia is an independent risk factor for coronary heart disease.1 When severe (blood triglycerides ≥1000mg/dl), there is also a greater associated risk of acute pancreatitis.2,3 In the context of hypertriglyceridaemia, pancreatic lipase acts on the triglycerides present in the pancreas and converts them into free fatty acids. These fatty acids are not toxic to the pancreas, as long as they are bound to albumin. However, when their levels increase above 10mmol/l (885mg/dl), the albumin becomes saturated and free fatty acids in the pancreas cause an inflammatory reaction that increases the risk of acute pancreatitis.4,5

The causes of this dyslipidaemia may be primary or secondary.6,7 Primary causes include familial hypertriglyceridaemia, familial combined hypercholesterolaemia, dysbetalipoproteinaemia and familial chylomicronaemia syndrome. In secondary dyslipidaemia, the most common causes are obesity, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, chronic renal failure, certain drugs and thyroid disorders. The initial treatment in patients with severe hypertriglyceridaemia is based on improving dietary habits (reducing calorie intake, low-fat diet, abstaining from alcohol), increasing physical exercise, controlling body weight and eliminating all secondary causes found.8 Supplements of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids), fibrates and niacin are the most common pharmacological measures in this clinical context.9–11 However, as is often the case in other chronic diseases, these patients are often found to be under-treated, with a lack of consistency in the way physicians deal with the problem.12–14

With the above considerations in mind, the aims of our study were: (a) to identify the clinical characteristics of patients with severe hypertriglyceridaemia and (b) to analyse the treatment prescribed by the physician in each case.

Materials and methodsStudy designWe conducted a cross-sectional study based on data collected from a secondary database (electronic medical record) which constitutes the sole hospital data archive. The electronic medical record is an instrument with adequate sensitivity for the recording of episodes, with “episode” being understood as anything that generates contact between the patient and the health service or that results in the doctor taking a particular type of action.

Inclusion criteriaAll patients over the age of 18 who had a blood triglyceride level ≥1000mg/dl in the period from 1 January 2011 to 31 December 2016 were included.

Exclusion criteriaNone.

Variables included in the analysisInformation was collected on the following variables at the time of the lipid profile measurement: age, gender, smoking history, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, body mass index, medication, blood creatinine, blood urea, blood glucose, latest ultrasensitive TSH, total cholesterol, HDL-C, LDL-C and HbA1c (in patients with diabetes). Information was obtained on history of pancreatitis and cardiovascular disease, classifying the population according to whether they were on primary or secondary prevention. We analysed the actions of the treating physicians in the 6 months after the finding of severe hypertriglyceridaemia, according to the following algorithm:

- 1)

Did they rule out secondary causes? We specifically looked at obesity, hypothyroidism, kidney failure, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, the use of drugs related to hypertriglyceridaemia and alcohol consumption.

- 2)

Did they refer the patient to a nutrition service?

- 3)

Did they recommend physical exercise?

- 4)

Did they prescribe any drug therapy? Which?

The treating physicians were in the areas of clinical medicine, general practice, endocrinology and cardiology.

The variables were tested for normality. Continuous data between two groups were analysed with the t-test if the variables had normal distribution and, if not, with the Mann–Whitney test. Categorical data were analysed with the Chi-squared test. The continuous variables were expressed as mean±standard deviation, while the categorical variables were expressed as absolute and relative frequencies. The strength of association was expressed as an odds ratio (OR) with its respective 95% confidence interval (95% CI). A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant, working with two-tailed tests. The STATA 13 program was used for the statistical analysis (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethical considerationsThe study was conducted following the recommendations on medical research of the Declaration of Helsinki, the Guidelines on Good Clinical Practices and the applicable ethical standards. The members of the study give assurances that measures will be implemented to protect the confidentiality of the data in accordance with applicable legal regulations (Personal Data Protection Act 25.326). The study protocol was approved by the institution's Ethics Committee.

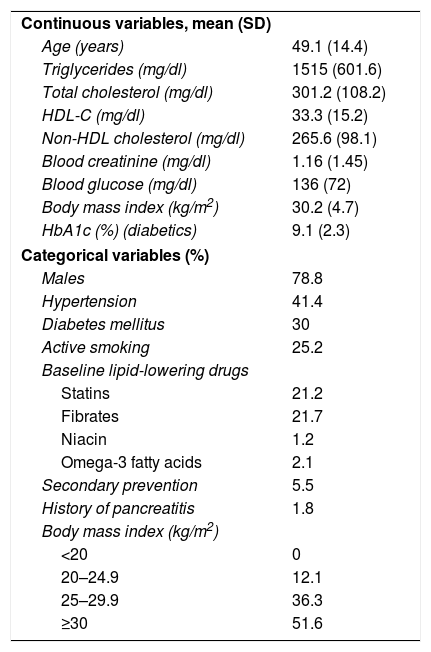

ResultsWe included 420 patients with severe hypertriglyceridaemia (mean age 49.1±11.4, 78.8% male) from a total of 162,000 medical records. Of the total, 25.2% were active smokers, 41.4% had hypertension and 30% had diabetes. Only 5.5% of the population had a previous history of cardiovascular events (secondary prevention). The mean triglyceride level was 1515±601.6mg/dl, with a median of 1329mg/dl (interquartile range 1174–1658). The characteristics of the population are shown in Table 1.

Characteristics of the population.

| Continuous variables, mean (SD) | |

| Age (years) | 49.1 (14.4) |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 1515 (601.6) |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 301.2 (108.2) |

| HDL-C (mg/dl) | 33.3 (15.2) |

| Non-HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 265.6 (98.1) |

| Blood creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.16 (1.45) |

| Blood glucose (mg/dl) | 136 (72) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 30.2 (4.7) |

| HbA1c (%) (diabetics) | 9.1 (2.3) |

| Categorical variables (%) | |

| Males | 78.8 |

| Hypertension | 41.4 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 30 |

| Active smoking | 25.2 |

| Baseline lipid-lowering drugs | |

| Statins | 21.2 |

| Fibrates | 21.7 |

| Niacin | 1.2 |

| Omega-3 fatty acids | 2.1 |

| Secondary prevention | 5.5 |

| History of pancreatitis | 1.8 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | |

| <20 | 0 |

| 20–24.9 | 12.1 |

| 25–29.9 | 36.3 |

| ≥30 | 51.6 |

SD: standard deviation.

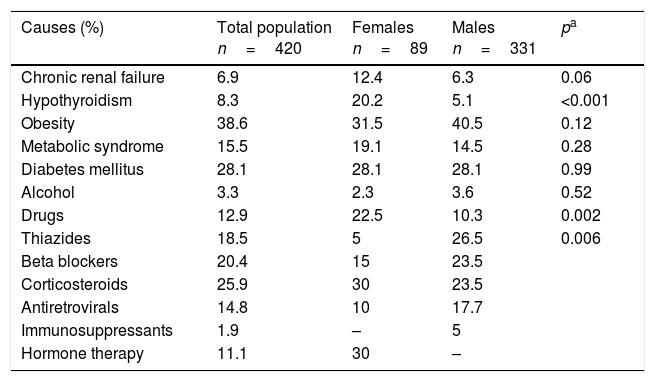

Only 1.8% of the population were found to have a history of acute pancreatitis. In 34.1% of the patients, no secondary cause to explain the hypertriglyceridaemia was found. The most common secondary causes found were obesity (38.6%), diabetes (28.1%) and metabolic syndrome (15.5%). Apart from hypothyroidism and the use of drug therapy, which were more common among females, there were no differences between males and females in most of the secondary causes assessed. Table 2 shows the potential causes of secondary hypertriglyceridaemia in our population.

Secondary causes of hypertriglyceridaemia.

| Causes (%) | Total population n=420 | Females n=89 | Males n=331 | pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic renal failure | 6.9 | 12.4 | 6.3 | 0.06 |

| Hypothyroidism | 8.3 | 20.2 | 5.1 | <0.001 |

| Obesity | 38.6 | 31.5 | 40.5 | 0.12 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 15.5 | 19.1 | 14.5 | 0.28 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 28.1 | 28.1 | 28.1 | 0.99 |

| Alcohol | 3.3 | 2.3 | 3.6 | 0.52 |

| Drugs | 12.9 | 22.5 | 10.3 | 0.002 |

| Thiazides | 18.5 | 5 | 26.5 | 0.006 |

| Beta blockers | 20.4 | 15 | 23.5 | |

| Corticosteroids | 25.9 | 30 | 23.5 | |

| Antiretrovirals | 14.8 | 10 | 17.7 | |

| Immunosuppressants | 1.9 | – | 5 | |

| Hormone therapy | 11.1 | 30 | – |

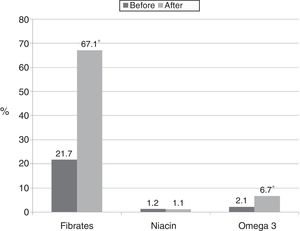

At the time of inclusion in the study, 21.7% of the subjects were being treated with fibrates. The most commonly used regimens were fenofibrate 200mg/day (40.4%) or 300mg/day (12.8%) and gemfibrozil 600mg/day (12.8%). Nine patients were taking omega-3 fatty acids at the time of determination, while only five patients were taking nicotinic acid. Among the patients who were taking statins (21.2%), the most common daily regimens were: atorvastatin 10mg (26.4%); atorvastatin 20mg (17.0%); rosuvastatin 10mg (13.2%); and simvastatin 10mg (13.2%).

Of the population evaluated, 32.6% did not have a medical follow-up appointment in the 6 months after the hypertriglyceridaemia finding. Of the patients who were followed up within 6 months, 49.1% received a formal recommendation to take up physical exercise and 44.2% were referred to a dietitian. In 40.7% of the cases, secondary causes were identified and measures taken to try to correct them.

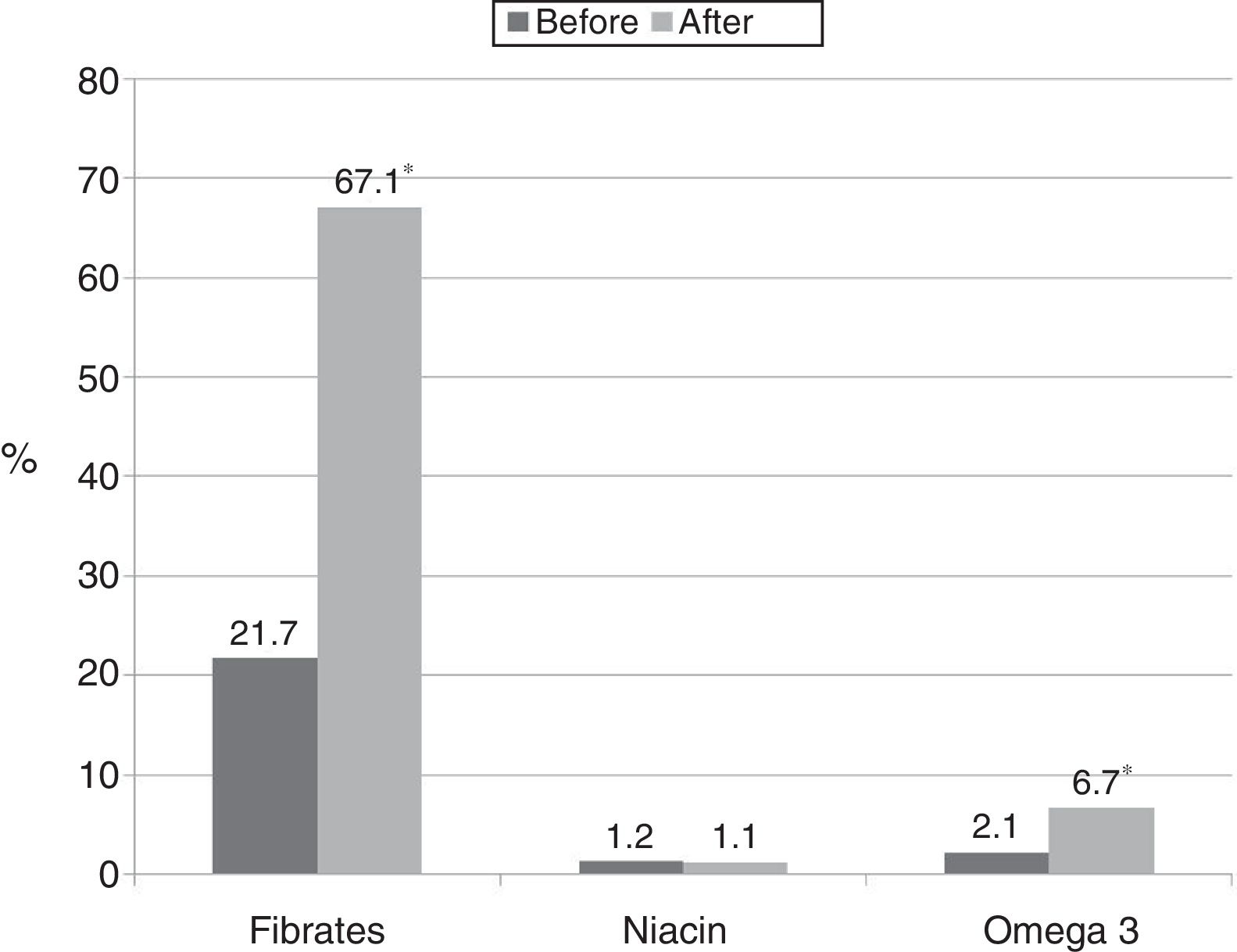

Fig. 1 shows the changes made by the treating physicians in prescriptions for drugs with demonstrated efficacy in hypertriglyceridaemia after discovering their patients’ triglyceride values.

In the population which was indicated fibrates after their test results, the most commonly prescribed treatment regimens were: fenofibrate 200mg/day (26.5%); gemfibrozil 900mg/day (19.3%); gemfibrozil 1200mg/day (12.0%); and fenofibrate 300mg/day (9.6%). Few patients received the indication of omega-3 fatty acids, with the most commonly prescribed dose being 1g/day (62.5%). Combination therapy with fibrates and omega-3 fatty acids was prescribed for 15%, one patient was treated concomitantly with niacin and omega-3 fatty acids and one received the combination of niacin and fibrates.

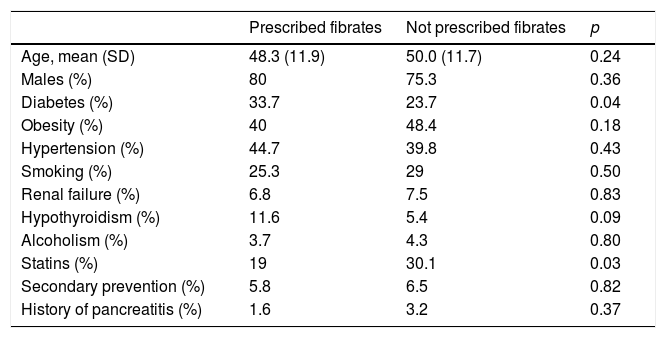

Previously having diabetes (OR: 1.64; 95% CI: 1.0–2.8) was associated with a greater likelihood of receiving fibrates, whereas previous treatment with statins correlated with less likelihood of receiving these drugs (OR: 0.54; 95% CI: 0.31–0.96) (Table 3).

Characteristics of the population according to whether or not they were prescribed fibrates after the discovery of severe hypertriglyceridaemia.

| Prescribed fibrates | Not prescribed fibrates | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 48.3 (11.9) | 50.0 (11.7) | 0.24 |

| Males (%) | 80 | 75.3 | 0.36 |

| Diabetes (%) | 33.7 | 23.7 | 0.04 |

| Obesity (%) | 40 | 48.4 | 0.18 |

| Hypertension (%) | 44.7 | 39.8 | 0.43 |

| Smoking (%) | 25.3 | 29 | 0.50 |

| Renal failure (%) | 6.8 | 7.5 | 0.83 |

| Hypothyroidism (%) | 11.6 | 5.4 | 0.09 |

| Alcoholism (%) | 3.7 | 4.3 | 0.80 |

| Statins (%) | 19 | 30.1 | 0.03 |

| Secondary prevention (%) | 5.8 | 6.5 | 0.82 |

| History of pancreatitis (%) | 1.6 | 3.2 | 0.37 |

SD: standard deviation.

The patients referred to nutrition were younger (OR: 0.97; 95% CI: 0.95–0.99), less likely to be treated with statins (OR: 0.45; 95% CI: 0.25–0.82) and more likely to be obese (OR: 3.2; 95% CI: 2.0–5.3). The patients recommended physical exercise were also younger (OR: 0.97; 95% CI: 0.95–0.99) and were less likely to be in secondary prevention (OR: 0.21; 95% CI: 0.05–0.73) or treated with statins (OR: 0.46; 95% CI: 0.26–0.82). The characteristics of the population according to whether or not they were advised to take up physical exercise and/or referred to a dietitian are shown in Table 4.

Characteristics of the population according to whether or not they were advised to take up physical exercise and referred to a dietitian.

| Advised to take up physical exercise | Not advised to take up physical exercise | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 47.7 (11.8) | 51.2 (11.6) | 0.01 |

| Males (%) | 78.4 | 78.5 | 0.99 |

| Diabetes (%) | 30.9 | 31.9 | 0.86 |

| Obesity (%) | 46 | 39.6 | 0.27 |

| Hypertension (%) | 37.4 | 48.6 | 0.06 |

| Smoking (%) | 28.1 | 25 | 0.56 |

| Renal failure (%) | 4.3 | 9.7 | 0.08 |

| Hypothyroidism (%) | 9.4 | 9.7 | 0.92 |

| Alcoholism (%) | 4.3 | 3.5 | 0.71 |

| Statins (%) | 15.8 | 29.2 | 0.007 |

| Secondary prevention (%) | 2.2 | 9.7 | 0.007 |

| History of pancreatitis (%) | 1.3 | 1.9 | 0.67 |

| Referred to dietitian | Not referred to dietitian | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 47 (11.5) | 51.4 (11.6) | 0.002 |

| Male (%) | 74.4 | 81.7 | 0.14 |

| Diabetes (%) | 29.6 | 31 | 0.79 |

| Obesity (%) | 58.4 | 30.4 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension (%) | 40.8 | 44.9 | 0.48 |

| Smoking (%) | 28 | 25.3 | 0.61 |

| Renal failure (%) | 5.6 | 8.2 | 0.39 |

| Hypothyroidism (%) | 11.2 | 8.2 | 0.40 |

| Alcoholism (%) | 2.4 | 5.1 | 0.25 |

| Statins (%) | 15.2 | 28.4 | 0.008 |

| Secondary prevention (%) | 2.9 | 6.8 | 0.10 |

| History of pancreatitis (%) | 1.6 | 2.5 | 0.59 |

SD: standard deviation.

In this study, and for the first time in our region, we have described the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of patients with severe hypertriglyceridaemia and the way in which the treating physicians deal with the problem. The triglyceride values in our population (median 1329mg/dl and mean 1515mg/dl) are higher than those reported in a Spanish registry which, like our study, included subjects with triglyceride levels >1000mg/dl (average 965mg/dl).15 Our population therefore represents a select group of subjects with severe hypertriglyceridaemia.

One important finding in our study was that approximately 80% of the population with severe hypertriglyceridaemia was male. This is consistent with figures reported in other registries in Europe and the United States.16,17 The lower prevalence in females may be explained by genetic, hormonal and metabolic mechanisms (for example, the ability in females to extract fat during the postprandial phase).18,19

Diagnosing the aetiology of the hypertriglyceridaemia can be difficult, among other reasons because there are usually multiple factors involved. In our study, we were able find at least one cause potentially related to the diagnosis of secondary hypertriglyceridaemia in two thirds of the population. However, that finding does not exclude the possibility that some patients may also have had genetic mutations associated with lipoprotein lipase deficiency. Only in 40.7% of the cases did the treating physicians identify a secondary cause and adopt measures to correct it. Consequently, in approximately 25% of the patients, no predisposing factors were detected.

In line with other publications, obesity, diabetes and metabolic syndrome were the main secondary causes.20,21 In this context, insulin resistance induced by visceral fat (partly mediated by the release of proinflammatory adipokines) produces an increase in the release of free fatty acids from adipocytes.22 That induces hepatic synthesis of triglycerides and apolipoprotein B, leading to an overproduction of VLDL particles rich in triglycerides, resulting in hypertriglyceridaemia in these patients.23

In contrast to other publications, we found a low percentage of patients whose hypertriglyceridaemia was associated with alcohol consumption.15 However, the difference could be explained by under-reporting of alcohol consumption in the medical records in our area. This same problem has been reported by other authors, although they were analysing data from surveys carried out in the general population and not from hospital medical records.24,25

The proportion of subjects with a history of pancreatitis was low in our study (<2%) compared to other previously published studies.15,20 Particular characteristics of our population, related to racial, epidemiological or aetiological factors (different proportion of genetic hypertriglyceridaemia and predisposing factors) may partially explain these findings.26,27

The underuse of drugs with demonstrated efficacy in cardiovascular prevention, such as statins, angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors and aspirin has been reported previously.28,29 However, we had little information about the use of fibrates in the context of severe hypertriglyceridaemia. Fibrates are the drugs of choice for the treatment of hypertriglyceridaemia.30 These drugs increase oxidation of fatty acids and synthesis of lipoprotein lipase, reduce apolipoprotein C-III expression and, as a consequence, reduce the production of VLDL and increase catabolism of particles rich in triglycerides.31 In our study, approximately two thirds of the patients who had a follow-up appointment in the 6 months after their lipid profile test were prescribed fibrates. However, only 12% of these subjects received the most effective fibrate at the maximum dose (gemfibrozil 1200mg/dl) to reduce their triglyceride levels.32

One of the factors that increase the risk of myopathy in subjects receiving statins is combination with fibrates.33 Nonetheless, fenofibrate is the preferred fibrate to be used in combination with statins as it does not interfere with their metabolism.30 In our study, previous use of statins was associated with less likelihood of being prescribed fibrates. In subjects with a history of diabetes, however, fibrates were more likely to be prescribed. These findings are probably partly explained by the fact that physicians who manage patients with diabetes seem to have a better understanding of how to adequately use these lipid-lowering drugs.

We found that more than half the subjects were not given a formal recommendation to take up physical exercise or referred to a dietitian, and that, if at all, these measures were more likely to be applied in the youngest patients. As expected, obese subjects were more often referred to a nutrition specialist, while a history of cardiovascular disease meant they were less likely to be advised to exercise.

In our study, we found very little use of niacin and omega-3 fatty acids. In the case of niacin, the negative results of the latest clinical trials to evaluate the use of nicotinic acid in patients in secondary prevention and the poor tolerance to this drug may have had an influence on the results.34,35 With respect to omega-3 fatty acids, not only were they used in very few patients, but they were also prescribed at lower-than-the-recommended doses.36,37

Our study does have certain limitations: (1) when using a secondary database (electronic medical record) there could be information biases; we believe that there may have been under-reporting in the survey of alcohol consumption as this is not recorded systematically; (2) some data on certain variables, such as waist circumference, presence of xanthomas/xanthelasmas, hereditary family history and apolipoprotein B levels, could not be reliably obtained retrospectively and could not therefore be included in the analysis; and (3) for methodological reasons, it was not possible to analyse the treatment methods prescribed by the doctors according to specialist area.

In conclusion, our study describes the characteristics of a population with severe hypertriglyceridaemia in Argentina for the first time. We have been able to highlight some secondary causes such as diabetes and obesity. The therapeutic measures prescribed by physicians were insufficient. Understanding the characteristics of this particular clinical scenario could improve the management of these patients, by allowing us to develop diagnostic and therapeutic algorithms that adapt to the real situation in each region.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.

Please cite this article as: Masson W, Rossi E, Siniawski D, Damonte J, Halsband A, Barolo R, et al. Hipertrigliceridemia grave. Características clínicas y manejo terapéutico. Clín Investig Arterioscler. 2018;30:217–223.