The “DAT-AP” (from the Spanish, “Dislipemia ATerogénica en Atención Primaria”, for Atherogenic Dyslipidaemia in Primary Care) study objective is to determine to what extent published consensus guidelines for the diagnostic and therapeutic management of AD are used in the primary care setting, and to evaluate the approach of the participating physicians towards the detection, diagnosis, and treatment of AD.

MethodsThis is descriptive, cross-sectional, multicentre study performed between January and May 2015 in primary care centres throughout Spain. Study data were collected in 2 independent blocks, the first addressing theoretical aspects of AD and the second, practical aspects (clinical cases)

ResultsThe theoretical part is in the process of publication. This manuscript depicts the clinical cases block. Although study participants showed good knowledge of the subject, the high prevalence of this disease requires an additional effort to optimise detection and treatment, with the implementation of appropriate lifestyle interventions and the prescription of the best treatment.

El objetivo del estudio “DAT-AP” (“Dislipemia ATerogénica en Atención Primaria”) es determinar en qué medida las guías de consenso publicadas sobre el manejo diagnóstico y terapéutico de la dislipidemia aterogénica (DA) son utilizadas en el entorno de atención primaria, así como evaluar el abordaje de los médicos participantes en cuanto a la detección, diagnóstico y tratamiento de la DA.

MétodosEstudio transversal, descriptivo y multicéntrico, realizado entre Enero y Mayo de 2015 en centros de AP de España. Los datos fueron recogidos en 2 bloques independientes, en el que el primero recoge aspectos teóricos de la DA y el segundo aspectos prácticos (casos clínicos)

ResultadosLa parte teórica está en proceso de publicación. Este manuscrito describe el bloque relativo a los casos clínicos. Aunque los participantes del estudio mostraron un buen conocimiento de la materia, la alta prevalencia de esta enfermedad requiere un esfuerzo adicional para optimizar la detección y el tratamiento con la implementación de medidas adecuadas sobre el estilo de vida y la prescripción del mejor tratamiento.

The worldwide obesity epidemic is progressing hand in hand with an increasing incidence of metabolic disorders, such as diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, and atherogenic dyslipidaemia (AD). AD is a typical characteristic in obese patients with metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes,1 and carries a significant cardiovascular risk.2,3 The AD lipid profile is determined by low HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C) levels, elevated triglycerides (TG), and the presence of small, dense LDL particles, a combination that is highly atherogenic. Given its nature, treating AD with statins is frequently insufficient to provide overall lipid profile control, and fails to eliminate the residual vascular risk attributable to the non-LDL components of this lipid abnormality.4

Numerous studies have shown that patients with AD benefit from medical treatment targeted at normalising HDL-C and TG,5–9 and this evidence has been integrated into recommendations published in clinical practice guidelines.10–12 However, while the understanding of the association between an elevated cardiovascular risk and low HDL-C or high TG levels is a complex matter, it is clear that this relationship impacts on both coronary and cerebrovascular disease.13,14

Appropriate diagnosis and therapeutic management of AD in the community would help to reduce the residual risk associated with this disease and affected patients would benefit. In this respect, primary care physicians play a very important role, since they can implement preventive measures in a large percentage of patients, more so than in the hospital setting or the specialised clinic.15

The main aim of this study was to determine to what extent published consensus guidelines for the diagnostic and therapeutic management of AD12 are used in the primary care setting, and to evaluate the approach of the participating physicians towards the detection, diagnosis, and treatment of AD.

Materials and methodsStudy design and participantsThe DAT-AP (Dislipemia ATerogénica en Atención Primaria − initials of Atherogenic Dyslipidaemia in Primary Care in Spanish) study is a descriptive, cross-sectional, multicentre study performed between January and May 2015 in primary care centres throughout Spain. This study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid. Study participants were primary care (PC) physicians involved in the treatment of AD, stratified according to the distribution of the population in Spain.

Study toolsThe scientific coordinators of the project developed a computer application to collect the necessary study data in 2 independent blocks, the first addressing theoretical aspects of AD and the second, practical aspects. The theoretical part consisted of 16 questions divided into 5 sections, according to the structure of the consensus document12: the nature of AD; impact and epidemiology of AD; cardiovascular risk associated with AD; detection, diagnosis and objectives for control; and treatment. An initial manuscript reporting the results of this first part is currently being prepared for publication. This article reports the results of the practical section, which consisted of 14 questions on 4 predefined clinical cases. The aim was to determine, according to the different items listed, the main features of the diagnostic and therapeutic approach in these proposed cases.

Each participating investigator was provided with a user name and password to access the online platformto complete the form. In no case was information collected from patients’ clinical records or from any specific patient.

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis was performed, using mean and standard deviation for quantitative variables and frequencies and percentages for qualitative variables. The statistical analysis was conducted using the statistical package SAS Service pack 3 version 9.1.3.

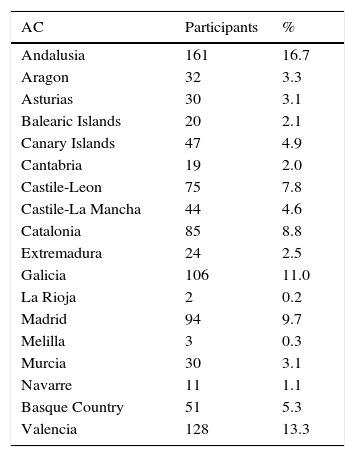

ResultsThe study participants comprised 991 PC physicians involved in the management of patients with AD. Table 1 shows the distribution of participating physicians in each autonomous community; representation was highest in Andalusia (16.7%), Valencia (13.3%) and Galicia (11.0%).

Participating family doctors by autonomous community (N=991).

| AC | Participants | % |

|---|---|---|

| Andalusia | 161 | 16.7 |

| Aragon | 32 | 3.3 |

| Asturias | 30 | 3.1 |

| Balearic Islands | 20 | 2.1 |

| Canary Islands | 47 | 4.9 |

| Cantabria | 19 | 2.0 |

| Castile-Leon | 75 | 7.8 |

| Castile-La Mancha | 44 | 4.6 |

| Catalonia | 85 | 8.8 |

| Extremadura | 24 | 2.5 |

| Galicia | 106 | 11.0 |

| La Rioja | 2 | 0.2 |

| Madrid | 94 | 9.7 |

| Melilla | 3 | 0.3 |

| Murcia | 30 | 3.1 |

| Navarre | 11 | 1.1 |

| Basque Country | 51 | 5.3 |

| Valencia | 128 | 13.3 |

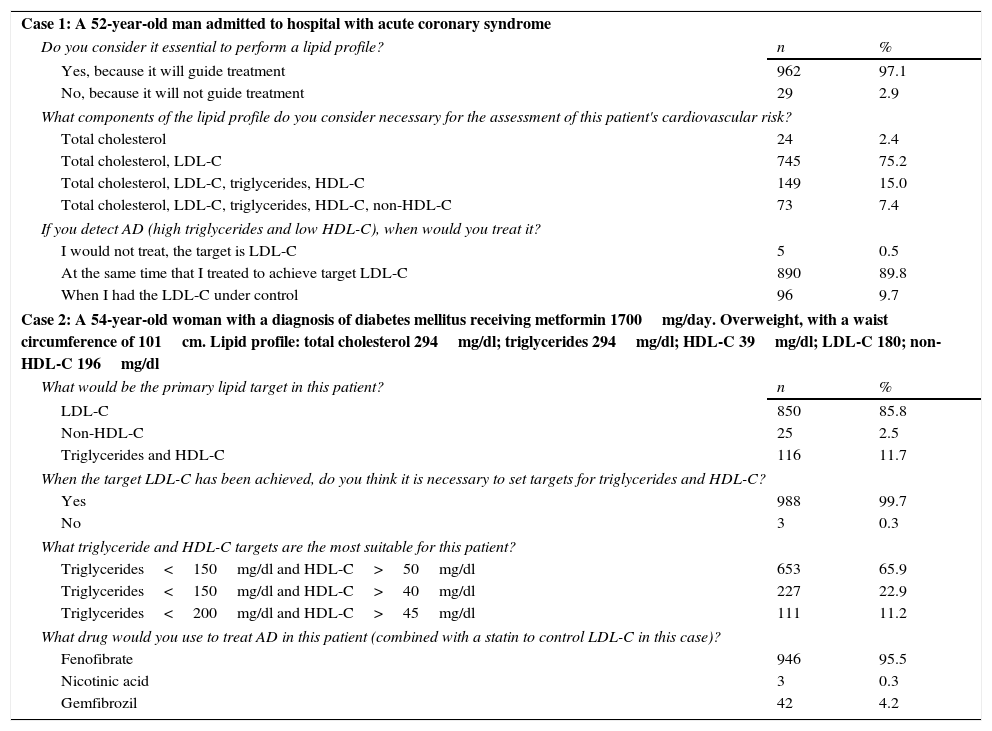

Case 1. A 52-year-old man admitted to hospital with acute coronary syndrome (ACS). In total, 97% of study participants considered that determination of the lipid profile was essential, since the results of that analysis would guide treatment (Table 2). Seventy-five percent of respondents considered that in this case it was essential to determine total cholesterol (TC) and LDL-C to assess the patient's cardiovascular risk. Around 90% indicated that if AD was detected, they would treat it at the same time as treating to achieve target LDL-C.

Response of participants to clinical cases 1 and 2.

| Case 1: A 52-year-old man admitted to hospital with acute coronary syndrome | ||

| Do you consider it essential to perform a lipid profile? | n | % |

| Yes, because it will guide treatment | 962 | 97.1 |

| No, because it will not guide treatment | 29 | 2.9 |

| What components of the lipid profile do you consider necessary for the assessment of this patient's cardiovascular risk? | ||

| Total cholesterol | 24 | 2.4 |

| Total cholesterol, LDL-C | 745 | 75.2 |

| Total cholesterol, LDL-C, triglycerides, HDL-C | 149 | 15.0 |

| Total cholesterol, LDL-C, triglycerides, HDL-C, non-HDL-C | 73 | 7.4 |

| If you detect AD (high triglycerides and low HDL-C), when would you treat it? | ||

| I would not treat, the target is LDL-C | 5 | 0.5 |

| At the same time that I treated to achieve target LDL-C | 890 | 89.8 |

| When I had the LDL-C under control | 96 | 9.7 |

| Case 2: A 54-year-old woman with a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus receiving metformin 1700mg/day. Overweight, with a waist circumference of 101cm. Lipid profile: total cholesterol 294mg/dl; triglycerides 294mg/dl; HDL-C 39mg/dl; LDL-C 180; non-HDL-C 196mg/dl | ||

| What would be the primary lipid target in this patient? | n | % |

| LDL-C | 850 | 85.8 |

| Non-HDL-C | 25 | 2.5 |

| Triglycerides and HDL-C | 116 | 11.7 |

| When the target LDL-C has been achieved, do you think it is necessary to set targets for triglycerides and HDL-C? | ||

| Yes | 988 | 99.7 |

| No | 3 | 0.3 |

| What triglyceride and HDL-C targets are the most suitable for this patient? | ||

| Triglycerides<150mg/dl and HDL-C>50mg/dl | 653 | 65.9 |

| Triglycerides<150mg/dl and HDL-C>40mg/dl | 227 | 22.9 |

| Triglycerides<200mg/dl and HDL-C>45mg/dl | 111 | 11.2 |

| What drug would you use to treat AD in this patient (combined with a statin to control LDL-C in this case)? | ||

| Fenofibrate | 946 | 95.5 |

| Nicotinic acid | 3 | 0.3 |

| Gemfibrozil | 42 | 4.2 |

Case 2. A 54-year-old woman with a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, currently receiving metformin 1700mg/day. Overweight, with a waist circumference of 101cm. Lipid profile: TC 294mg/dl; triglycerides 294mg/dl; HDL-C 39mg/dl; LDL-C: 180; non-HDL-C 196mg/dl. Eighty-six percent of participants stated that the primary lipid objective in this patient would be to control LDL-C. Nearly 100% stated that once the LDL-C therapeutic target had been achieved, targets would have to be set for control of triglycerides and HDL-C: 66% stated that the most suitable targets for this patient would be triglycerides<150mg/dl and HDL-C>50mg/dl. For 95% of the respondents, the drug of choice would be fenofibrate plus a statin, to control LDL-C while simultaneously treating AD (Table 2).

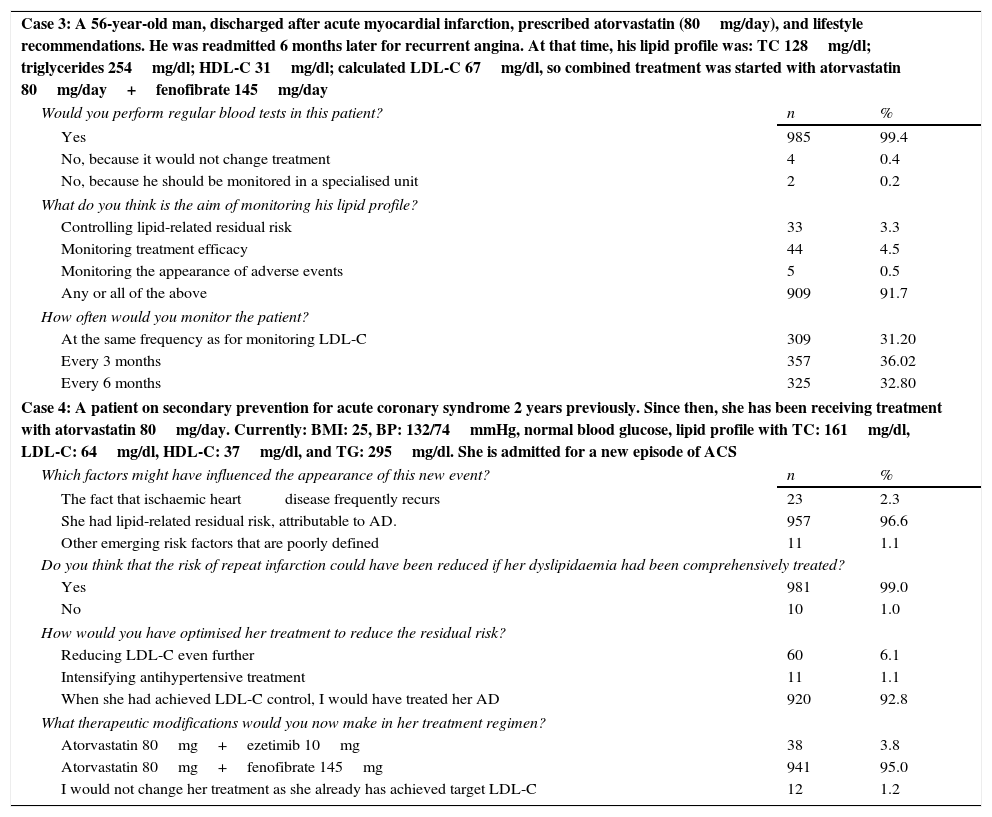

Case 3. A 56-year-old man, discharged after an acute myocardial infarction. He was prescribed atorvastatin (80mg/day) and given appropriate recommendations on lifestyle changes. He was readmitted 6 months later for recurrent angina. At that time his lipid profile was: TC 128mg/dl; triglycerides 254mg/dl; HDL-C 31mg/dl; calculated LDL-C 67mg/dl, so combined treatment was started with atorvastatin 80mg/day+fenofibrate 145mg/day. Ninety-nine percent of the physicians stated that they would perform regular lipid monitoring in this patient. According to 91.7% of them, the aim of lipid monitoring would be to control lipid-related residual risk, monitor treatment efficacy and/or monitor the appearance of adverse events. In total, 36% of the participants would monitor every 3 months, and 33% every 6 months (Table 3).

Response of participants to clinical cases 3 and 4.

| Case 3: A 56-year-old man, discharged after acute myocardial infarction, prescribed atorvastatin (80mg/day), and lifestyle recommendations. He was readmitted 6 months later for recurrent angina. At that time, his lipid profile was: TC 128mg/dl; triglycerides 254mg/dl; HDL-C 31mg/dl; calculated LDL-C 67mg/dl, so combined treatment was started with atorvastatin 80mg/day+fenofibrate 145mg/day | ||

| Would you perform regular blood tests in this patient? | n | % |

| Yes | 985 | 99.4 |

| No, because it would not change treatment | 4 | 0.4 |

| No, because he should be monitored in a specialised unit | 2 | 0.2 |

| What do you think is the aim of monitoring his lipid profile? | ||

| Controlling lipid-related residual risk | 33 | 3.3 |

| Monitoring treatment efficacy | 44 | 4.5 |

| Monitoring the appearance of adverse events | 5 | 0.5 |

| Any or all of the above | 909 | 91.7 |

| How often would you monitor the patient? | ||

| At the same frequency as for monitoring LDL-C | 309 | 31.20 |

| Every 3 months | 357 | 36.02 |

| Every 6 months | 325 | 32.80 |

| Case 4: A patient on secondary prevention for acute coronary syndrome 2 years previously. Since then, she has been receiving treatment with atorvastatin 80mg/day. Currently: BMI: 25, BP: 132/74mmHg, normal blood glucose, lipid profile with TC: 161mg/dl, LDL-C: 64mg/dl, HDL-C: 37mg/dl, and TG: 295mg/dl. She is admitted for a new episode of ACS | ||

| Which factors might have influenced the appearance of this new event? | n | % |

| The fact that ischaemic heart disease frequently recurs | 23 | 2.3 |

| She had lipid-related residual risk, attributable to AD. | 957 | 96.6 |

| Other emerging risk factors that are poorly defined | 11 | 1.1 |

| Do you think that the risk of repeat infarction could have been reduced if her dyslipidaemia had been comprehensively treated? | ||

| Yes | 981 | 99.0 |

| No | 10 | 1.0 |

| How would you have optimised her treatment to reduce the residual risk? | ||

| Reducing LDL-C even further | 60 | 6.1 |

| Intensifying antihypertensive treatment | 11 | 1.1 |

| When she had achieved LDL-C control, I would have treated her AD | 920 | 92.8 |

| What therapeutic modifications would you now make in her treatment regimen? | ||

| Atorvastatin 80mg+ezetimib 10mg | 38 | 3.8 |

| Atorvastatin 80mg+fenofibrate 145mg | 941 | 95.0 |

| I would not change her treatment as she already has achieved target LDL-C | 12 | 1.2 |

Case 4. A patient on secondary prevention after ACS 2 years previously. Since then, she has been receiving treatment with atorvastatin 80mg/day. Currently: BMI: 25, BP: 132/74mmHg, normal blood glucose, lipid profile with TC: 161mg/dl, LDL-C: 64mg/dl, HDL-C: 37mg/dl, and TG: 295mg/dl. She is admitted for a new episode of ACS. In total, 97% of participants stated that the factor that may have influenced the appearance of this new event was the patient's residual lipid risk, attributable to AD, and 99% believed that her risk of repeat infarction would have been less if her dyslipidaemia had been treated comprehensively. Ninety-three percent of respondents stated that they would have optimised this patient's treatment to reduce the residual risk, treating her AD after LDL-C control had been achieved. Ninety-five percent answered that they would add 145mg fenofibrate to her current atorvastatin treatment (Table 3).

DiscussionIn this study, we analysed clinical approaches to 4 proposed clinical cases illustrating different situations, in order to determine the extent to which PC physicians selected from all autonomous communities in Spain understand and apply AD consensus recommendations.12 The questions were primarily drawn up to investigate the diagnostic and/or therapeutic approach in typical cases commonly seen in routine practice, and to analyse the different diagnostic and therapeutic strategies in each case.

It is widely agreed that the benefit provided by intensive reduction of LDL-C has led to the general acceptance of “LDL-C-centred” measures.16 However, many patients with target LDL-C levels continue to have a persistent cardiovascular risk or residual risk associated with the presence of AD, particularly patients with type 2 diabetes, abdominal obesity, and/or metabolic syndrome. Almost all the physicians who participated in this study were aware of the importance of performing a lipid profile for the comprehensive assessment of a patient who has suffered an ACS. The importance of low HDL-C as a source of cardiovascular risk is well established,17,18 yet a substantial number of physicians still do not include HDL-C levels when determining lipid profiles, despite the evidence of an inverse prognostic relationship between HDL-C and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, irrespective of LDL-C concentrations.19 The role of triglycerides in coronary heart disease is also of key importance. A metaanalysis of 29 prospective studies revealed an odds ratio for coronary risk of 1.72 when individuals with triglycerides in the upper tertile (corresponding to >178mg/dl) were compared with those with levels in the lower tertile (<115mg/dl), after adjustment for other principal cardiovascular risk factors.20 Moreover, high non-fasting triglyceride levels can be a marker for cardiovascular risk.21

More recently, non-HDL cholesterol figures have gained importance as an indicator of cardiovascular risk, and on occasions are even thought to have more prognostic value than LDL-C.22 A metaanalysis of studies published between 1994 and 2008 showed that individuals who achieved target LDL-C but did not achieve target non-HDL-C levels had a 32% higher risk than those who achieved both objectives.23 This may be attributed to the fact that non-HDL-C concentrations reflect not only LDL-C, but also all atherogenic particles in plasma corresponding to lipoproteins that contain apolipoprotein B.24 The European Atherosclerosis Society has set non-HDL-C as a secondary target in the treatment of dyslipidaemia,11 calculated as target LDL-C plus 30mg/dl. This is a parameter that is easy to calculate (TC minus HDL-C) and does not involve any additional cost.

In high-risk patients, such as those with type 2 diabetes, excess weight, and high cholesterol and triglyceride levels (see study case 2), little concordance emerged on the definition of the therapeutic target after LDL-C has been controlled: only 66% of participants indicated that in women, triglyceride control is achieved at a level of less than 150mg/dl and HDL-C should be higher than 50mg/dl, in accordance with international recommendations.11,16 This highlights some lack of clarity regarding the treatment of complex cases that, in the absence of a history of cardiovascular disease, must be considered as candidates for primary prevention of atherothrombotic and cardiovascular episodes.25 The situation is different in patients who are already receiving prophylactic treatment (secondary prevention). Despite lipid-lowering treatment, the role of AD as a determinant element among factors contributing to residual cardiovascular risk26 is well known, as confirmed by almost 97% of the participants. Clinicians, then, must (and do, according to the results of this survey) give great importance to regular monitoring of lipid levels, treatment efficacy, and detection of possible adverse effects. However, the frequency of monitoring remains controversial, and, as has been stated, is often influenced more by administrative and financial concerns than by clinical considerations.27

One strategy found to be useful in the overall control of dyslipidaemia is to use combined lipid-lowering treatment, with the administration of a statin to lower cholesterol in association with a fibrate for AD.28–30 Fenofibrate was the option used by most of our participants (over 95%) in combination with statins, compared to the more minority choices of nicotinic acid or gemfibrozil. Indeed, clinical practice guidelines and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) recommend fenofibrate for the treatment of mixed hyperlipidemia together with a statin, when triglycerides and HDL-C are inadequately controlled. The safety of this combination has been demonstrated in several studies,31–33 and there is evidence that fenofibrate confers additional clinical benefit on renal function34,35 and carbohydrate metabolism.36

Some limitations to the interpretation of our results must be taken into account. As in any qualitative study, our results are exploratory and the conclusions cannot be generalised. As this was a survey, the results represent certain opinions or knowledge, rather than objective data. We do not know if the participating physicians had received specific training in AD or not, nor did we determine the proportion of patients similar to the proposed cases seen in their daily clinical practice. When an individual case presents, other factors such as adherence, drug interactions, and the psychosocial situation must be taken into account in the comprehensive assessment of the patient, and these aspects were not addressed in this study.

ConclusionsThis study is a first attempt to evaluate the approach and knowledge of physicians treating AD in the PC setting, as an initial step towards detecting possible shortcomings in training and the application of expert consensus guidelines in AD. Although study participants showed good knowledge of the subject, the high prevalence of this disease requires an additional effort to optimise detection and treatment, with the implementation of appropriate lifestyle interventions and the prescription of the best treatment. Emphasis must be placed on the need to perform a complete lipid profile for an overall assessment of the patient's cardiovascular risk, and to treat the residual risk associated with high triglycerides and low HDL-C with the recommended combination of a statin and fenofibrate.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors state that no human or animal experiments have been performed for this research.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors state that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors state that no patient data appears in this article.

FundingThis study has been financed by Mylan.

Conflict of interestsThe authors state that they have no conflict of interests. All authors contributed equally to the preparation of this article.

The authors thank Mylan for sponsoring and funding this study, and the SANED group for their technical support during the study and for the statistical analysis of the data.