Fragile X syndrome is an inherited form of mental retardation with a connective tissue component involving mitral valve prolapse. The most frequent manifestations of fragile X syndrome are learning disability, orofacial morphological alterations and macroorchidism.

The usefulness of advanced haemodynamic monitoring for goal-directed therapy is increasingly high during neurosurgical procedures. Non-invasive cardiac output monitoring may be considered as a new alternative for emergency neurosurgical procedures.

Our aim was to detect haemodynamic changes in a syndromic fragile X patient, given the usual concomitant presentation of cardiovascular disease, such as mitral valve prolapse and dilated aortic root, in an attempt at obtaining the best intraoperative and postoperative neurological outcomes without worsening cardiovascular function, by means of individualized intra-operative goal directed therapy. This type of non-invasive monitoring allows surgery to proceed without delay and provides excellent information of the haemodynamic status.

This syndrome is relevant due to its anaesthetic implications and the paucity of cases published to date.

El síndrome X frágil es una forma hereditaria de retraso mental con una afectación de tejido conectivo que produce prolapso de la válvula mitral. Las manifestaciones más frecuentes del síndrome X frágil son la dificultad en el aprendizaje, alteraciones morfológicas orofaciales y macroorquidismo.

La utilidad de la monitorización hemodinámica avanzada para terapia dirigida por objetivos es cada vez mayor durante los procedimientos neuroquirúrgicos. La monitorización no invasiva de gasto cardiaco puede considerarse una nueva alternativa en los procedimientos neuroquirúrgicos emergentes.

Nuestro objetivo fue detectar los cambios hemodinámicos en un paciente sindrómico X frágil que suelen presentar patología cardiovascular, como prolapso mitral y dilatación de la raíz aórtica, intentando obtener los mejores resultados neurológicos intraoperatorios y posoperatorios sin deteriorar la función cardiovascular individualizada por una terapia guiada por objetivos. Este tipo de monitorización no invasiva permite desarrollar la intervención quirúrgica sin demora, aportando gran información del estado hemodinámico. Este síndrome es relevante debido a sus implicaciones anestésicas y los pocos casos publicados hasta la fecha.

Fragile X syndrome (FXS) is the most common cause of inherited mental retardation1,2 accounting for 30% of the cases,3 with an associated connective tissue disorder that leads to mitral valve prolapse (MVP) in most subjects.4 The goal in our clinical case was to individualize anaesthetic management in this syndrome given difficult airway control and the associated cardiovascular pathology. Non-invasive cardiac output monitoring was used during the emergency craniotomy in order to reduce morbidity with the help of goal-directed therapy and avoid delaying the surgery, considering that this approach only requires placement of a finger device that provides all the relevant information pertaining to the patient's haemodynamic status.

Clinical caseA 38 year-old male patient with FXS, severe mental retardation, and refractory epileptic encephalopathy who suffered head injury following a tonic–clonic seizure, with acute left frontoparietal subdural haematoma requiring emergent craniotomy.

Once monitoring with arterial blood pressure (ABP), electrocardiography (EKG), pulse oximetry, bispectral index (BIS) and non-invasive cardiac output (Nexfin® – BMEYE, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) was established, cefazoline 2g and midazolam 5mg were given IV through a peripheral venous line because the patient was uncooperative. Propofol 120mg, remifentanil 0.1μg/kg/min and 50mg of rocuronium were used for anaesthesia induction, with subsequent successful endotracheal intubation with the help of Glidescope® videolaryngoscopy. Mechanical ventilation was started and right internal jugular venous access was established under ultrasound guidance.

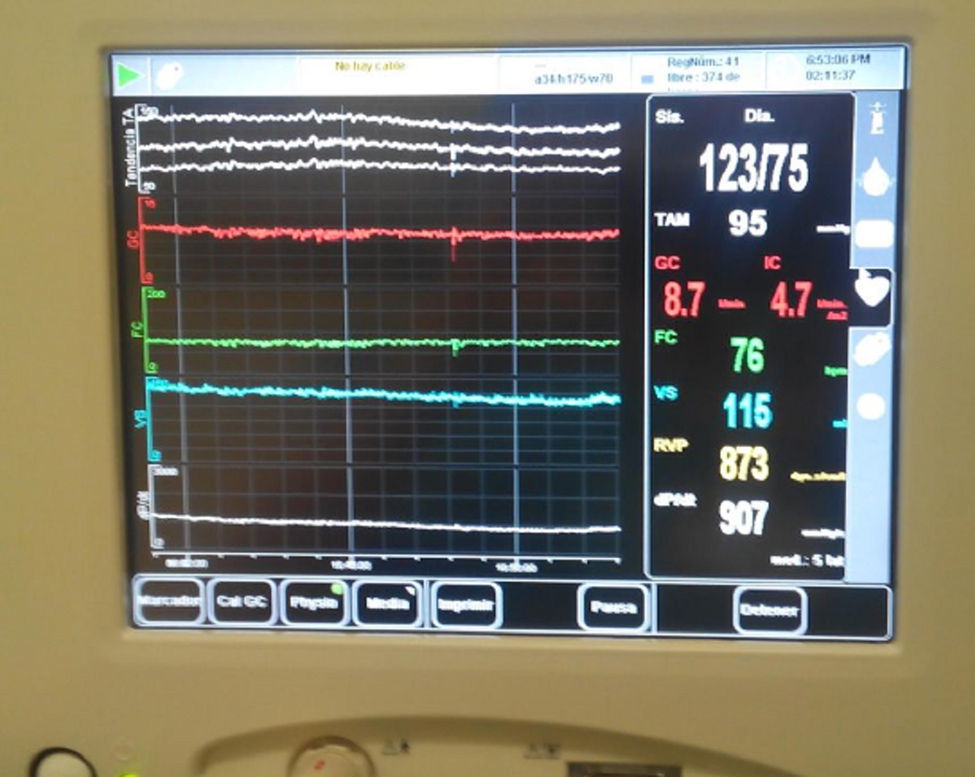

Propofol and remifentanil were used for anaesthesia maintenance. Mannitol 25g and furosemide 20mg were required for lowering intracranial pressure (ICP) (from 22mmHg initially down to 4mmHg after haematoma removal). ICP was monitored using a subdural intracranial pressure sensor. Goal directed therapy (GDT) was implemented during the intraoperative period based on cardiac output values obtained after the initial administration of 1000mL, increased to 4000mL in response to signs of hypovolemia. An infusion of 0.1μg/kg/min of noradrenaline was required in order to normalize extremely low initial values of systemic vascular resistance and to maintain mean arterial pressure at around 90mmHg, promoting adequate cerebral perfusion (Fig. 1). Haemodynamic stability was maintained, vasoactive amine perfusion was removed and the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit with adequate sedation and analgesia, and under mechanical ventilation.

DiscussionDescribed by Martin and Bell in 1943,3 FXS has typical physical and behavioural characteristics.1 Prevalence in males (1:3.600) is higher than in females (1:8.000), it is being associated with the X chromosome.1 It is caused by an abnormal expansion of the cytosine–guanine–guanine triplet (CGG) in the FMR1 gene (Fragile X Mental Retardation 1 gene) on chromosome X(Xq27.3), blocking the production of the FMR1 gene protein (FMRP).5

The phenotypic characteristics of this syndrome may have significant anaesthetic implications, among other findings, because of craniofacial abnormalities. Physical characteristics include macrocephaly,3,6 hyperteolirsm, strabismus, prognathism,3 large prominent ears, and postpubertal marcroorchidism.7

Dental implantation is abnormal, with abraded dental surfaces as well as large crowns that create severe bone–teeth discrepancies,8 limiting mouth opening and impairing the placement of the endotracheal tube.

Our patient had prognathism as well as abnormal dental implantation limiting mouth opening to 3cm. Because of an anticipated difficult airway, we decided to use the Glidescope® videolaryngoscope,9 with successful endotracheal intubation and minimum stimulus, thus avoiding an increase in intracranial pressure.

FXS patients have excess joint laxity,7 flat feet, pectus excavatum and scoliosis. Patient positioning on the operating table with adequate support points is essential in order to prevent joint dislocations and gonadal compression.4

In 80–90% of FXS cases there is moderate to severe mental retardation.3 Autism, hyperactivity, agitation and anxiety are also frequent,3 hence the need for adequate sedation before induction, because they are usually uncooperative.

In 15–20%3 of cases there are partial complex and generalized tonic clonic seizures that are usually benign3 and disappear before 20 years of age. The right premedication may reduce surgical stress by raising the convulsive threshold perioperatively.

From the cardiovascular standpoint, 80% of cases may be associated with MVP with no previous episodes of chest pain or palpitations4 but which may give rise to intraoperative arrhythmias.4 Occasionally, there is also aortic root dilatation,4 in which case it is advisable to use adequate monitoring in order to implement GDT and create better conditions for improved results in major surgery.10 Because our patient was transferred from another hospital as a vital emergency, we were unable to confirm the presence of a MVP. However, given the high incidence of this disorder and the fact that symptoms become exacerbated by anaesthesia induction, leading to cardiovascular collapse,11 we decided to perform non-invasive cardiac output monitoring.

The main objective of the anaesthetic management was to prevent any reduction in left ventricular volume during systole in order to reduce mitral valve prolapse.11

Reduced venous return and vascular resistance, tachycardia and increased contractility are not well tolerated.11 During general anaesthesia, the use of vasopressors is recommended in order to maintain ABP, together with short-acting beta-blockers for heart rate control, end-diastolic and systolic volume preservation, and mitral prolapse control.11

Management is different in cases associated with mitral regurgitation because maintenance of higher heart rates shortens diastolic time and reduces regurgitation volumes.12

Pulse pressure variation (PPV) and systolic volume variation (SVV) are dynamic predictors of response to fluids in patients under mechanical ventilation. Their measurement is usually invasive by means of the signal derived from the ABP curve. Non-invasive CO monitoring using an inflatable cuff with an in-built photoelectric plethysmographic device provides continuous ABP measurement13 based on the development of a pulsatile discharge from the arterial walls in the finger.13

SVV and PPV measurements without the need to use an intra-arterial catheter offers an advantage in emergency surgery, particularly in neurosurgery, where any delay in starting the intervention may determine worse clinical outcomes. GDT allows for early detection of pathophysiological changes and individualized adjustment of intraoperative haemodynamic management.10 Invasive ABP monitoring with an intra-arterial catheter13 is considered the gold standard.14 However, non-invasive measurement of dynamic predictors of response to fluid replacement has been shown to have high specificity and sensitivity,13 with improved safety and comfort.15 This system can be used on top of non-invasive ABP monitoring in haemodynamically stable patients under general anaesthesia, with the benefit of providing beat-to-beat ABP measurements.14 However, its concomitant use with the PICCO® transpulmonary thermodilution monitor for measuring cardiac output is controversial.15,16

In summary, we discuss the anaesthetic management of patients with FXS, given the low incidence of this disorders and the very few reports found in the anaesthesia literature. We believe that non-invasive cardiac output monitoring is a new option for emergency neurosurgical procedures and in patients with heart disease, considering that it shortens anaesthesia time and provides reliable parameters for GDT. Moreover, we believe that videolaryngoscopy is the first choice for managing a predictably difficult airway in which endotracheal intubation might result in a significant increase in ICP.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

FundingWe received no funding for our work.

Conflicts of interestThere are no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Guerrero-Domínguez R, López-Herrera-Rodríguez D, Beato-López FJ, Jiménez I. Manejo hemodinámico mediante monitor no invasivo de gasto cardiaco para craneotomía urgente en el síndrome x frágil: reporte de caso. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2016;44:48–51.