Postoperative pain can cause complications, prolonged hospital stays and has often been poorly assessed.

ObjectivesTo determine the intensity of pain in patients operated on using a visual analog scale (VAS) and to identify variables associated with a lack of control in seven cities in Colombia.

Materials and methodsCross-sectional study in patients older than 18 years between 1st January and 30th September, 2014 in eight clinics across Colombia. The intensity of postoperative pain was assessed with a VAS 4h after the procedure. Socio-demographic, clinical and pharmacological variables were considered. Multivariate analysis was done using SPSS 22.0.

ResultsA total of 1015 patients were evaluated. The mean age was 42.5±17.1 years, and 63.8% were female. The mean pain level was 38.8±19.4mm, with a total of 600 (59.1% of patients) without pain control. Dipyrone was the most used analgesic, followed by morphine and tramadol. Being treated at Nuestra Señora del Rosario Clinic in Ibagué (OR: 1.65; 95%CI: 1.096–2.479; p=0.016), coming from urban areas (OR: 1.71; 95%CI: 1.186–2.463; p=0.005), being subjected to major surgery (OR: 2.02; 95%CI: 1.316–3.109; p=0.001), emergency surgery (OR: 1.46; 95%CI: 1.065–2.013; p=0.019), and suffering nausea (OR: 2.05; 95%CI: 1.341–3.118; p=0.001) were statistically associated with no pain control.

ConclusionNone of the clinics had acceptable percentages of patients with pain controlled 4h after surgery. Clinical practice guides should be incorporated, institutional policies should be defined, health personnel should be trained, and the outcomes of the interventions should be evaluated.

El dolor postoperatorio puede causar complicaciones, prolongar la estancia hospitalaria y frecuentemente es mal valorado.

ObjetivosDeterminar la intensidad del dolor en pacientes intervenidos quirúrgicamente mediante una escala visual analógica (EVA) y determinar las variables asociadas a la falta de control en siete ciudades de Colombia.

Materiales y métodosEstudio de corte transversal en pacientes mayores de 18 años entre el 1 de enero y 30 de septiembre del año 2014 en 8 clínicas de Colombia. Se valoró la intensidad del dolor postoperatorio mediante EVA a las 4 horas del procedimiento. Se consideraron variables sociodemográficas, clínicas y farmacológicas. Se hizo análisis multivariado con SPSS 22.0.

ResultadosSe evaluó un total de 1015 pacientes, con edad promedio 42,5±17,1 años, y 63,8% eran mujeres. La media del nivel de dolor fue 38,8±19,4 mm, con un total de 600 (59,1% de pacientes) sin control del dolor. Dipirona fue el analgésico más empleado, seguido de tramadol y morfina. Ser tratado en la clínica Nuestra Señora del Rosario de Ibagué (OR:1,65; IC95%:1,096–2,479; p=0,016), provenir de área urbana (OR:1,71; IC95%:1,186-2,463; p=0,005), ser sometido a cirugía mayor (OR:2,02; IC95%:1,316-3,109; p=0,001), de urgencia (OR:1,46; IC95%:1,065-2,013; p=0,019), y sufrir náuseas (OR:2,05; IC95%:1,341-3,118; p=0,001) se asociaron estadísticamente con no controlar el dolor.

ConclusiónEn ninguna de las clínicas había porcentajes aceptables de pacientes con dolor controlado a las 4 horas después de la cirugía. Se deben incorporar guías de práctica clínica, definir políticas institucionales, capacitar al personal sanitario y evaluar resultados de las intervenciones.

Pain in the postoperative period is that symptom that presents in surgical patients due to a pre-existing condition, the procedure that they underwent (associated with drainage, nasogastric tubes, complications, etc.) or the combination of the base disease and the surgery.1 Acute pain may be caused by the surgery or by a trauma, bringing with it potentially adverse psychological and systemic responses unless they are adequately treated.2

The body's response to acute pain may impede the return of pulmonary function to its normal state, especially in the elderly population. It can also modify aspects of the response to injuries under stress and alter cardiovascular function with an increase in heart workload and oxygen consumption. This can even lead to ischemic events that affect morbidity and postoperative mortality.3 Furthermore, the pain may provoke immobility that delays recovery, prolongs the hospital stay, and contributes to thromboembolic complications. In addition, the improper management of postoperative pain may cause long term pain.4

The main reason for which pain is not adequately controlled is related to the administration of medications in lower doses and dosage guidelines different from the recommendations. Moreover, it has been observed that pain in hospitalized patients is more prevalent than is reported. Therefore, the identification and treatment of these patients is a relevant health problem.2

Pain relief through the administration of analgesics or blockage of the afferent neural pathways with local anesthetic improves the physiological response to the pain and the injury, reducing complications.5 How appropriate management of pain after its correct identification with a visual analog scale (VAS) shortens hospital stays and is associated with reduced costs has also been reported on.2,6

Previous studies carried out with patients submitted to surgical procedures in two hospital institutions in a city in Colombia showed that more than half of patients remained without pain control 4h after surgery, and other authors have reported similar values of lack of pain control.7–9 However, experiments where less than 11% of postsurgical patients remain without pain control have also been published.9,10 Since evidence is still lacking regarding how post-surgical pain is being managed in Colombia, we sought to determine the intensity of this pain as perceived by patient who had undergone surgery in the early postoperative period, assessing the symptom 4h after surgery with a VAS. Socio-demographic, clinical, and pharmacological variables—associated with pain control or lack thereof—were also defined in seven Colombian cities in order to optimize the management of pain control.

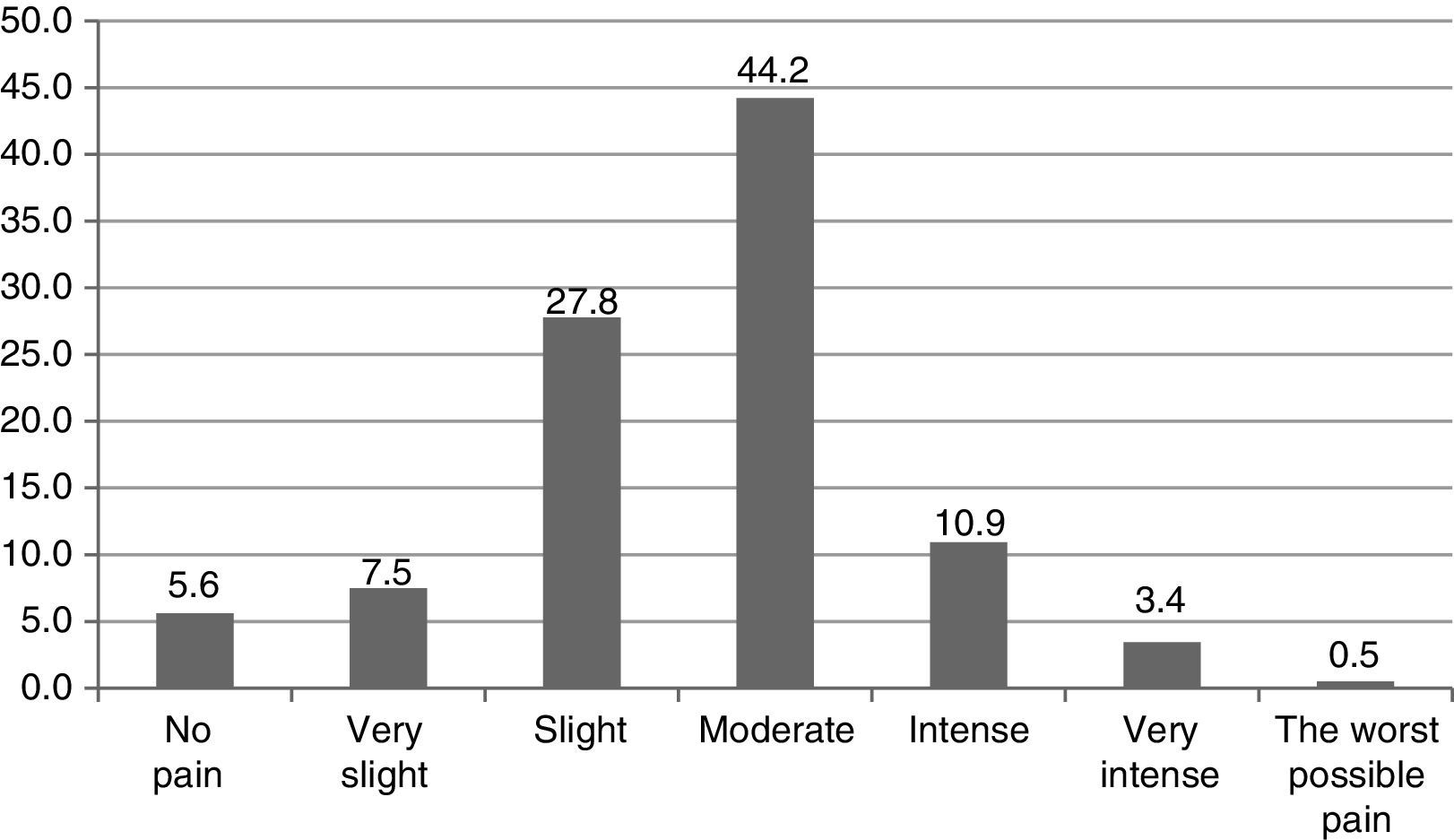

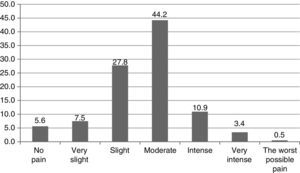

Materials and methodsA cross-sectional study was carried out in eight different clinics in seven Colombian cities (Popayán, Ibagué, Cali, Manizales, Medellín, Cartagena, Barranquilla) in a population of patients over 18 years of age operated on between 7:00am and 6:00pm between January 1st and September 30th, 2014. The evaluation of the intensity of postoperative pain was measured with a VAS in millimeters (mm). In the VAS, five levels of intensity were established. 0 and 100 corresponded to absolute values and were considered independent categories, but the following reference values were also determined: (0) 0mm as no pain, (1) 1–19mm very slight pain, (2) 20–39mm slight pain, (3) 40–59mm medium pain, (4) 60–79mm intense pain, (5) 80–99mm very intense pain, and (6) 100mm worst possible pain. Uncontrolled pain was defined as reported pain above 40mm and, therefore, pain was considered to be controlled when the values were less than or equal to 39mm.6,11,12

With the goal of evaluating the management of immediate postoperative pain, 4h after the end of the procedure, researchers proceeded to interview and evaluate the individual perception of the intensity of the pain by applying the VAS to each of the patients that agreed to participate after signing an informed consent form. Properly trained physicians and nurses in each of the clinics obtained the information. Furthermore, researchers had access to the patients’ medical history and the surgical lists. A data collection instrument created by the researchers that also took the following variables into consideration was used:

Previous socio-demographic and toxicological variablesAge, sex, health insurance plan (subsidized or contributory), socio-economic level (low, medium, high), educational level (primary, secondary, post-secondary), residence (urban or rural), tobacco use, alcohol consumption, consumption of psychoactive substances.

Clinical variablestype of surgical procedure (general, neuro-, urological, plastic, orthopedic, otorhinolaryngological, or gynecological surgery, etc.), complications during surgery and in postoperative period, type of anesthesia, estimated risk of surgery (high, moderate, low).

Pharmacological variablesanalgesics prescribed in the immediate postoperative period until 4h after, grouped according to their pharmacological class and their use in monotherapy and combined therapy, dose, dosage interval of each, associated adverse drug effects, and use of analgesic premedication. The use of morphine, meperidine, and fentanyl was determined as total opioid agonists. The use of tramadol as a partial opioid agonist was also determined. Also, non-opioid analgesics (acetaminophen, dipyrone) and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) were considered.

The protocol was submitted for approval to the Bioethics Committee of the Universidad Tecnológica de Pereira in the category “research with risk below the minimum” in accordance with resolution No. 8430 of 1993 of the Ministry of Health of Colombia, guaranteeing the confidentiality of each patients in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The analysis was done with the statistical package SPSS version 22.0 for Windows (IBM, USA). Student's t-test or ANOVA were used for the comparison of quantitative variables, and the X2 test was used to compare categorical variables. Logistical regression models were used with pain control (yes/no) being the dependent variable and, for independent variables, those that were significant in the bivariate analysis. A level of statistical significance of p<0.05 was determined.

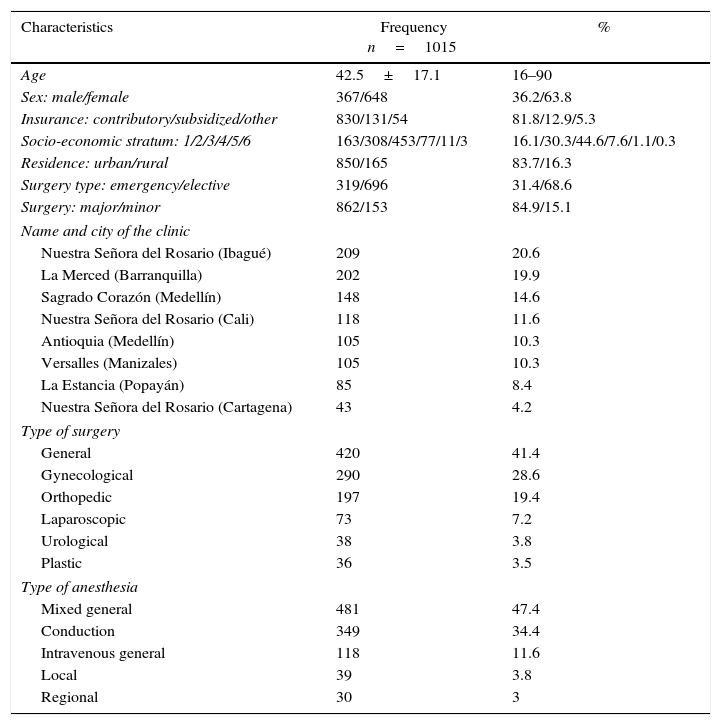

ResultsA total of 1015 patients that were operated upon in the eight clinics included in the study were evaluated. In Table 1, the main characteristics of the evaluated population can be observed. It was found that the average level of pain in the entire population studies was 38.8±19.4mm (range: 0–100mm), with a total of 600 patients (59.1%) without pain control, while 415 (40.9%) asserted that this symptom was controlled. 14.4% manifested having intense or very intense pain, and it is worth highlighting that 5 patients (0.5%) expressed having the worst pain in their lives.

Socio-demographic, medical, and surgical characteristics of 1015 patients operated on in eight clinics in Colombia, 2014.

| Characteristics | Frequency n=1015 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 42.5±17.1 | 16–90 |

| Sex: male/female | 367/648 | 36.2/63.8 |

| Insurance: contributory/subsidized/other | 830/131/54 | 81.8/12.9/5.3 |

| Socio-economic stratum: 1/2/3/4/5/6 | 163/308/453/77/11/3 | 16.1/30.3/44.6/7.6/1.1/0.3 |

| Residence: urban/rural | 850/165 | 83.7/16.3 |

| Surgery type: emergency/elective | 319/696 | 31.4/68.6 |

| Surgery: major/minor | 862/153 | 84.9/15.1 |

| Name and city of the clinic | ||

| Nuestra Señora del Rosario (Ibagué) | 209 | 20.6 |

| La Merced (Barranquilla) | 202 | 19.9 |

| Sagrado Corazón (Medellín) | 148 | 14.6 |

| Nuestra Señora del Rosario (Cali) | 118 | 11.6 |

| Antioquia (Medellín) | 105 | 10.3 |

| Versalles (Manizales) | 105 | 10.3 |

| La Estancia (Popayán) | 85 | 8.4 |

| Nuestra Señora del Rosario (Cartagena) | 43 | 4.2 |

| Type of surgery | ||

| General | 420 | 41.4 |

| Gynecological | 290 | 28.6 |

| Orthopedic | 197 | 19.4 |

| Laparoscopic | 73 | 7.2 |

| Urological | 38 | 3.8 |

| Plastic | 36 | 3.5 |

| Type of anesthesia | ||

| Mixed general | 481 | 47.4 |

| Conduction | 349 | 34.4 |

| Intravenous general | 118 | 11.6 |

| Local | 39 | 3.8 |

| Regional | 30 | 3 |

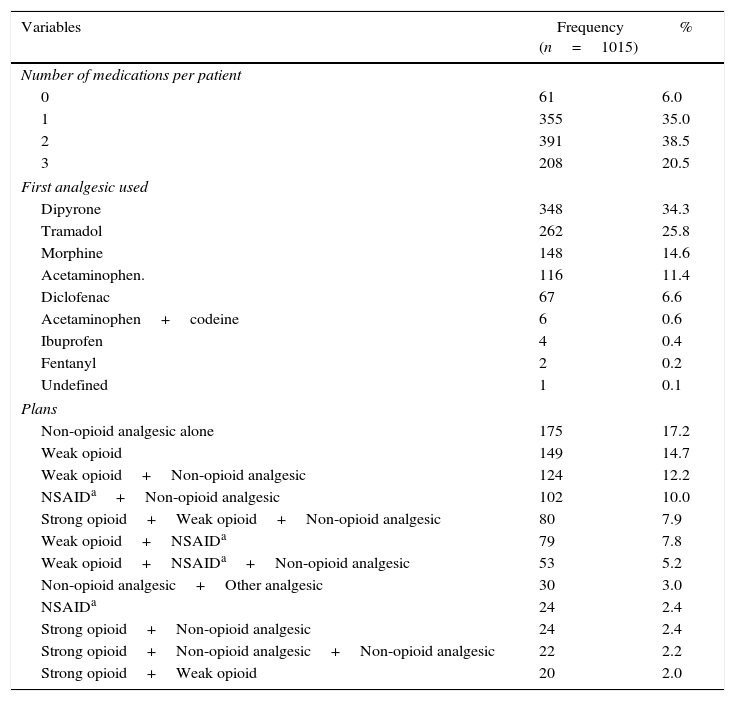

The distribution of patients according to the range of pain found in the evaluation is shown in Fig. 1. Table 2 brings together information on the number of medications used per patient, the first analgesic used, and their main associations, ordered by frequency of use. Dipyrone was the most used drug in monotherapy and combined therapy, followed by tramadol and morphine.

Most used medications and anesthetic plans in the postoperative period in 1015 patients operated on in 8 clinics in Colombia, 2014.

| Variables | Frequency (n=1015) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Number of medications per patient | ||

| 0 | 61 | 6.0 |

| 1 | 355 | 35.0 |

| 2 | 391 | 38.5 |

| 3 | 208 | 20.5 |

| First analgesic used | ||

| Dipyrone | 348 | 34.3 |

| Tramadol | 262 | 25.8 |

| Morphine | 148 | 14.6 |

| Acetaminophen. | 116 | 11.4 |

| Diclofenac | 67 | 6.6 |

| Acetaminophen+codeine | 6 | 0.6 |

| Ibuprofen | 4 | 0.4 |

| Fentanyl | 2 | 0.2 |

| Undefined | 1 | 0.1 |

| Plans | ||

| Non-opioid analgesic alone | 175 | 17.2 |

| Weak opioid | 149 | 14.7 |

| Weak opioid+Non-opioid analgesic | 124 | 12.2 |

| NSAIDa+Non-opioid analgesic | 102 | 10.0 |

| Strong opioid+Weak opioid+Non-opioid analgesic | 80 | 7.9 |

| Weak opioid+NSAIDa | 79 | 7.8 |

| Weak opioid+NSAIDa+Non-opioid analgesic | 53 | 5.2 |

| Non-opioid analgesic+Other analgesic | 30 | 3.0 |

| NSAIDa | 24 | 2.4 |

| Strong opioid+Non-opioid analgesic | 24 | 2.4 |

| Strong opioid+Non-opioid analgesic+Non-opioid analgesic | 22 | 2.2 |

| Strong opioid+Weak opioid | 20 | 2.0 |

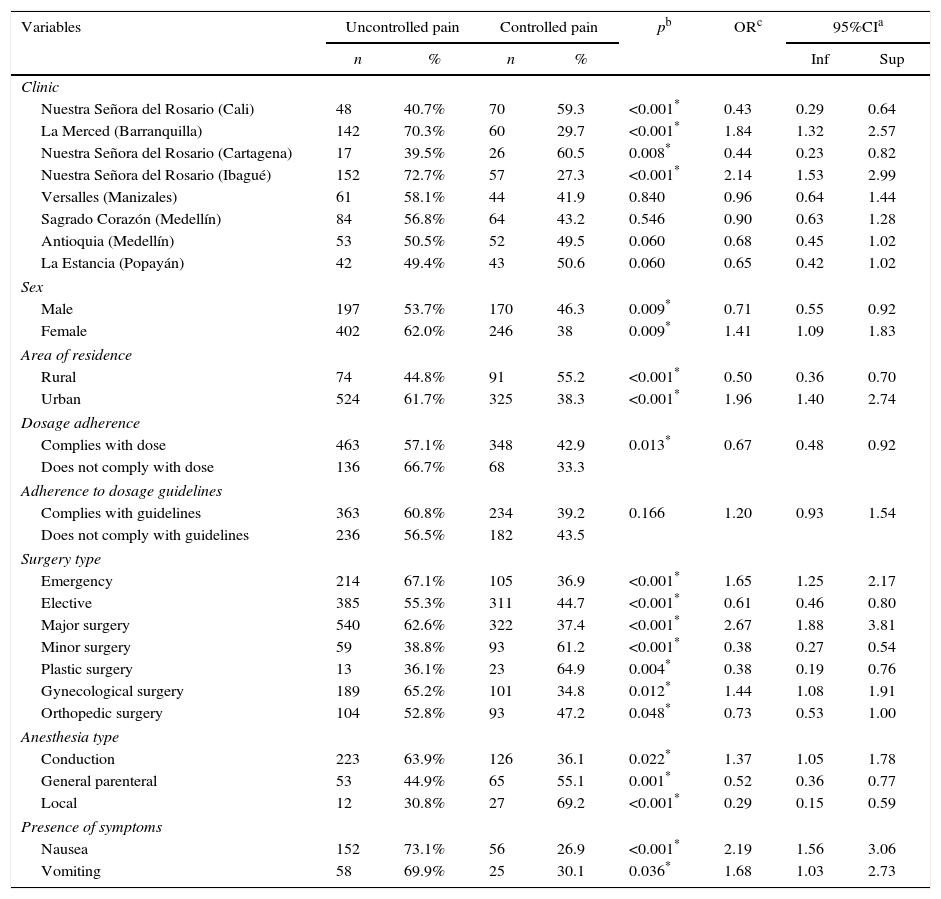

In Table 3, the results of the bivariate analyses can be seen. They show the subgroups of patients with controlled pain versus those for whom pain was uncontrolled. It was found that the variables of being treated in the La Merced Clinic in Barranquilla, being treated in Nuestra Señora del Rosario Clinic in Ibagué, being a woman, coming from an urban area, being operated on in the emergency ward, undergoing major surgery, undergoing gynecological surgery, receiving conduction anesthesia, and suffering from nausea and vomiting were associated in a statistically significant way with a greater risk of not controlling pain. Meanwhile, being treated in the Nuestra Señora del Rosario clinics in Cali and Cartagena, being a man, coming from a rural area, undergoing elective, minor or orthopedic surgery, receiving general or local anesthesia, and complying with the dose of the first analgesic were all statistically associated with a lower risk of not controlling pain.

Bivariate analysis of pain control after 4h versus the main socio-demographic, pharmacological, and clinical variables of the patients operated on in 8 clinics in Colombia, 2014.

| Variables | Uncontrolled pain | Controlled pain | pb | ORc | 95%CIa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | Inf | Sup | |||

| Clinic | ||||||||

| Nuestra Señora del Rosario (Cali) | 48 | 40.7% | 70 | 59.3 | <0.001* | 0.43 | 0.29 | 0.64 |

| La Merced (Barranquilla) | 142 | 70.3% | 60 | 29.7 | <0.001* | 1.84 | 1.32 | 2.57 |

| Nuestra Señora del Rosario (Cartagena) | 17 | 39.5% | 26 | 60.5 | 0.008* | 0.44 | 0.23 | 0.82 |

| Nuestra Señora del Rosario (Ibagué) | 152 | 72.7% | 57 | 27.3 | <0.001* | 2.14 | 1.53 | 2.99 |

| Versalles (Manizales) | 61 | 58.1% | 44 | 41.9 | 0.840 | 0.96 | 0.64 | 1.44 |

| Sagrado Corazón (Medellín) | 84 | 56.8% | 64 | 43.2 | 0.546 | 0.90 | 0.63 | 1.28 |

| Antioquia (Medellín) | 53 | 50.5% | 52 | 49.5 | 0.060 | 0.68 | 0.45 | 1.02 |

| La Estancia (Popayán) | 42 | 49.4% | 43 | 50.6 | 0.060 | 0.65 | 0.42 | 1.02 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 197 | 53.7% | 170 | 46.3 | 0.009* | 0.71 | 0.55 | 0.92 |

| Female | 402 | 62.0% | 246 | 38 | 0.009* | 1.41 | 1.09 | 1.83 |

| Area of residence | ||||||||

| Rural | 74 | 44.8% | 91 | 55.2 | <0.001* | 0.50 | 0.36 | 0.70 |

| Urban | 524 | 61.7% | 325 | 38.3 | <0.001* | 1.96 | 1.40 | 2.74 |

| Dosage adherence | ||||||||

| Complies with dose | 463 | 57.1% | 348 | 42.9 | 0.013* | 0.67 | 0.48 | 0.92 |

| Does not comply with dose | 136 | 66.7% | 68 | 33.3 | ||||

| Adherence to dosage guidelines | ||||||||

| Complies with guidelines | 363 | 60.8% | 234 | 39.2 | 0.166 | 1.20 | 0.93 | 1.54 |

| Does not comply with guidelines | 236 | 56.5% | 182 | 43.5 | ||||

| Surgery type | ||||||||

| Emergency | 214 | 67.1% | 105 | 36.9 | <0.001* | 1.65 | 1.25 | 2.17 |

| Elective | 385 | 55.3% | 311 | 44.7 | <0.001* | 0.61 | 0.46 | 0.80 |

| Major surgery | 540 | 62.6% | 322 | 37.4 | <0.001* | 2.67 | 1.88 | 3.81 |

| Minor surgery | 59 | 38.8% | 93 | 61.2 | <0.001* | 0.38 | 0.27 | 0.54 |

| Plastic surgery | 13 | 36.1% | 23 | 64.9 | 0.004* | 0.38 | 0.19 | 0.76 |

| Gynecological surgery | 189 | 65.2% | 101 | 34.8 | 0.012* | 1.44 | 1.08 | 1.91 |

| Orthopedic surgery | 104 | 52.8% | 93 | 47.2 | 0.048* | 0.73 | 0.53 | 1.00 |

| Anesthesia type | ||||||||

| Conduction | 223 | 63.9% | 126 | 36.1 | 0.022* | 1.37 | 1.05 | 1.78 |

| General parenteral | 53 | 44.9% | 65 | 55.1 | 0.001* | 0.52 | 0.36 | 0.77 |

| Local | 12 | 30.8% | 27 | 69.2 | <0.001* | 0.29 | 0.15 | 0.59 |

| Presence of symptoms | ||||||||

| Nausea | 152 | 73.1% | 56 | 26.9 | <0.001* | 2.19 | 1.56 | 3.06 |

| Vomiting | 58 | 69.9% | 25 | 30.1 | 0.036* | 1.68 | 1.03 | 2.73 |

For the multivariate analysis, it was found that the variables that were statistically associated with not managing to control pain were being treated in the Nuestra Señora del Rosario Clinic in Ibagué (OR: 1.65; 95%CI: 1.096–2.479; p=0.016), coming from an urban area (OR: 1.71; 95%CI: 1.186–2.463; p=0.005), undergoing major surgery (OR: 2.02; 95%CI: 1.316–3.109; p=0.001), or emergency surgery (OR: 1.46; 95%CI: 1.065–2.013; p=0.019), and suffering from nausea in the postoperative period (OR: 2.05; 95%CI: 1.341–3.118; p=0.001). Meanwhile, the variables of being operated on in the Nuestra Señora del Rosario Clinic in Cali (OR: 0.38; 95%CI: 0.182–0.802; p=0.011), Nuestra Señora del Rosario Clinic in Cartagena (OR: 0.43; 95%CI: 0.216–0.859; p=0.017), complying with the dosage (OR: 0.56; 95%CI: 0.363–0.863; p=0.009), and complying with the dosage guidelines (OR:0.58; 95%CI:0.408–0.830; p=0.003) of the first analgesic were all statistically associated with a lower risk on not being able to control the pain.

DiscussionIt was possible to determine that the pain of the majority of patients operated on in the eight clinics around the country was not controlled 4h after the end of the procedure. Percentages of pain control oscillated between 27.3% and 59.3% and differ greatly from the findings of a meta-analysis with more than 20000 patients in Europe, where only 11.0% of patients had uncontrolled pain, and are similar to percentages reported in Colombia and in some countries like the USA (59–75%), the UK (33%), France (46%), and Spain (68%).7–9,13 These data are worrying since this condition in not appropriately and opportunely evaluated, and, when it is treated, its management is not optimal.

The anatomical and physiological principles implicated in the transmission of pain have been clarified, these being the scientific basis of the application of the concept of multimodal analgesia—that is, the combination of two or more drugs and/or analgesic methods in order to boost the analgesia and reduce the side-effects. However, despite this, many patients that are being operated on in the country are not receiving the appropriate care to avoid pain after the procedures are performed. This affects their quality of life, puts them at risk for complications, lengthens their hospital stays, and increased the costs of care.14–16 As such, physicians should become more aware and be more trained in pain management in order to improve this indicator. The role of local anesthetics, NSAIDs, neuromodulators, and opioids is recognized, this last category considered the keystone of the management of moderate to severe acute postoperative pain.1

It should be taken into account that only 59.0% of patients received multimodal therapy, and 35.0% received a single analgesic. This, together with the choice of dipyrone in monotherapy, the incompliance with the dosage and improper guidelines for the administration of the medication, can be determinants for the high proportion of patients with uncontrolled pain, which has already been described in other studies.7,13

Findings related to the higher frequency of uncontrolled pain in women, in individuals from urban areas, in those suffering from nausea or vomiting, or those submitted to major surgery have already been described by other authors and are explained by cultural characteristics, the reduction of the dosage to avoid undesired effects, or the level of tissue compromise, respectively.2,7–9,17 Furthermore, some predictors of moderate to severe postoperative pain have been identified—among them, highly intense pain (9 or 10 values in the VAS) or patient anxiety before the procedure—in young patients, women, patients undergoing long surgeries or appendectomies, cholecystectomies, hemorrhoidectomies, and tonsillectomies.18 The researchers clarify that when they found patients without pain control, they notified the person responsible for their health care.

It has already been demonstrated how interventions that improve the way analgesics, and especially opioids, are used increasing the number of patients with appropriate pain control.19 The hospitals that achieved the best results in the control of this symptom have developed special education programs aimed especially at nurses, particularly those in the Gyneco-obstetric services, and these activities are repeated annually.1 Furthermore, services dedicated to controlling acute pain by following clinical practice guides are progressively more common in different countries, and they have managed to improve the effectiveness and quality of care for patients and the satisfaction with the service received, showing that, through these services, fewer patients complain of painful discomfort, nausea and vomiting is diminished, and hospital stays and costs are reduced.20 The use of multimodal anesthesia generates a positive impact on the quality of care, recovery, accelerates hospital discharge, and reduces the risk of chronic postoperative pain. It is know that the results with morphine are superior to those with tramadol.18,19 In this study, none of the clinics assessed had a specialized pain care service.

Recommendations from the American Society of Anesthesiology for the management of acute perioperative pain include anesthesiologists offering information and training to other physicians and nurses in the effective and safe use of the different available therapeutic options (early assessment, non-pharmacological techniques, and more sophisticated pain control procedures), and anesthesiologists providing information on the use of analgesic medications, especially multimodal anesthesia and regional blocks. Also, the establishment of standardized institutional policies that encourage proper pain control is a determinant of success, along with the application of the drug regimen following an established schedule, in the optimal dosages, and in the route and duration that the patient requires.18 Working proposals exist involving crisis resource management with simulation strategies that can be applied in postoperative care units that have generated change in the mental frameworks of professionals involved in treating pain, and they have demonstrated success in improving the control of this symptom.21 Evaluating the preferences of physicians when choosing an analgesic, and the reasons involved in this decision, is fundamental to establish new strategies that take this into account and are able to improve the quality of pain care.22

Some of the limitations are related to the fact that the VAS provides a one-dimensional measurement that evaluates only the sensorial component and does not involve affective and cognitive components of the patient.10 Moreover, other techniques of pain control in these patient were not considered, generally because they were not routinely used in the participating clinics. Nevertheless, the large size of the sample, the heterogeneity of the population, the rigor of the information collection, and the availability of trustworthy data from clinics in different cities are strengths that should be taken into account and that can contribute to the knowledge on this subject in the country.

It can be concluded that in none of the eight clinics were there acceptable percentages of patients with controlled pain 4h after surgery, despite the fact that better results were found in some than in others. The results were significantly better in patients cared for in the clinics in Cali and Cartagena, and when the doses and dosage guidelines were followed, than when they were attended to in the clinic in Ibagué, came from an urban area, had nausea in the postoperative period, or underwent emergency or major surgeries. These findings should be useful for those responsible for care in these clinics so that they might incorporate clinical practice guides, define institutional policies focusing on appropriate pain management, train medical and paramedical personnel that are in direct contact with the patients, and evaluate the results of their interventions. The directors of the other clinics in Colombia ought to ask themselves if postoperative pain is controlled or not in their institutions and then define conducts to guarantee the quality of the care.

FinancingThis study received financing from Audifarma S.A. and from the Universidad Tecnológica de Pereira.

Bioethical declarationThe protocol was submitted for approval to the Bioethics Committee of the Universidad Tecnológica de Pereira in the category of “research with risk below the minimum” in accordance with resolution No. 8430 of 1993 of the Ministry of Health of Colombia, guaranteeing the confidentiality of the data of each patient in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Machado-Alba JE, Ramírez-Sarmiento JO, Salazar-Ocampo DF. Estudio multicéntrico sobre efectividad de control del dolor postquirúrgico en pacientes de Colombia. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2016;44:114–120.