Remifentanil has an attractive pharmacological profile for use in obstetric analgesia as a technique for mass application, with similar benefits and satisfaction as epidural analgesia.

ObjectiveTo assess the efficacy, equivalence and safety of remifentanil vs. epidural analgesia in obstetrics.

MethodsSystematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials using the Cochrane methodology.

ResultsNo equivalence was found in relation to epidural analgesia; however, efficacy was found in the remifentanil group at different time points during the evaluation. The incidence of adverse effects was similar in the two groups, except for nausea.

ConclusionsRemifentanil is not equivalent to epidural analgesia but could certainly decrease the intensity of pain.

El remifentanilo presenta un perfil farmacológico atractivo para definirse como analgesia obstétrica, dada la necesidad de una técnica de empleo masivo, con similares beneficios y satisfacción que la analgesia epidural.

ObjetivoEvaluar la eficacia, la equivalencia y la seguridad del remifentanilo vs. Analgesia epidural en analgesia obstétrica.

MétodosRevisión sistemática y meta-análisis de experimentos clínicos siguiendo la metodología Cochrane.

ResultadosNo hallamos equivalencia con respecto a analgesia epidural, pero sí eficacia en el grupo de remifentanilo a diferentes horas de evaluación. La incidencia de efectos adversos fue similar en ambos grupos, salvo para las náuseas.

ConclusionesEl remifentanilo puede no ser equivalente a la analgesia epidural, pero podría disminuir la intensidad del dolor consonante con los niveles de satisfacción de cada artículo.

Lumbar epidural analgesia is considered the gold standard in the treatment of labour-associated pain due to its effectiveness and low frequency of adverse effects.1–4 However, its use is restricted in patients with absolute contraindications and in those who refuse to receive it because of its invasive nature and its potential complications.5–7 Consequently, various authors have written about the need for an equivalent option for patients who cannot benefit from its application.

The use of opioids intravenously or in regional techniques during labour is quite controversial because, on the one hand, they induce respiratory depression in the mother and, on the other hand, because of potential respiratory, cardiovascular and tissue perfusion complications in the newborn.8–10 Over the past decade, the massive use of the potent opioid remifentanil in anaesthesia11,12 has given rise to multiple reviews and editorials highlighting the strong profile of this drug for the control of pain during labour.13 However, due to the low epidemiological power of this work, no recommendation has been structured. In 2008, after the publication by Volmanen et al.14 a whole new experimental stage was set in motion for assessing the efficacy of remifentanil and its equivalence with epidural analgesia.

The goal of this study is to establish the equivalence in terms of efficacy and safety of intravenous remifentanil compared to epidural analgesia for the treatment of acute pain in labour, and to suggest a recommendation in this regard. The method to achieve this objective was a systematic review and meta-analysis. The question proposed to achieve this objective was: Is remifentanil as effective and safe as epidural analgesia for labour-associated pain?

MethodsAnalytical study with a systematic review design and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials controlled with epidural analgesia, conducted in accordance with the Cochrane collaboration methodology15 and pursuant to the recommendations of the PRISMA Declaration.16 The evaluation was performed using the R-Amstar tool.17

Selection criteriaStudies: Randomized clinical trials controlled with epidural analgesia.

Patients included: Women in labour with an indication for obstetric analgesia.

Interventions:Two groups were defined as follows:

Remifentanil group: Patients assigned to analgesic intervention with intravenous remifentanil, irrespective of the specific technique used (patient controlled analgesia – PCA – or infusion, or combined PCA and infusion).

Epidural group: Patients assigned to analgesic intervention with epidural analgesia, irrespective of the specific technique used (patient controlled epidural analgesia – PCEA – or infusion, or combined PCEA and infusion).

Outcomes:Pain: Assessment of pain intensity using the visual analogue scale (VAS) from 0 to 10, summarized as means and standard deviations according to each study, and developed in accordance with the protocol.

Other outcomes assessed in accordance with the definition in each study:

- -

Conditions: foetal bradycardia, respiratory depression, caesarean section, instrumented delivery, nausea.

- -

Behaviours: sedation, Apgar test and umbilical artery pH.

The search was conducted in the following sources:

- -

Primary: PubMed, Embase, Lilacs, Cochrane, Ebsco.

- -

Secondary: ACP Journal Club, NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination; National Library of Medicine Health Service Research, Scirus.

- -

Dissertations and grey literature: SIGLEá, NTIS, Pascal and Cinhal, New York Academy of Sciences Grey Sources, Clinical Medicine Netprints, Collection Index to Theses, Canada Portal Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations, Australian Digital Theses Program ProQuest, NHMRC Science.

- -

Search of papers registered and in development on the World Health Organization platform (www.who.int/trialsearch).

- -

Based on the articles found during the systematic review, the search was completed using a snowball strategy and manual online search of bibliographic references included in each article. Search strategies were used for each of the cited databases, developed from the one generated for Medline – PubMed (“remifentanil” [Supplementary Concept] or “remifentanil” [All Fields]) and (“labour” [All Fields] or “work” [MeSH Terms] or “work” [All Fields] or “labor” [All Fields] or “labor, obstetric” [MeSH Terms] or “labor” [All Fields]) and (“obstetric” [All Fields]) or “obstetric labor” [All Fields]) and (Clinical Trial [ptyp] or Randomized Controlled Trial [ptyp]).

– No date or language restrictions were applied.

Data collection and analysisStudy identification and selectionEach title was evaluated by the reviewer group and classified as relevant, irrelevant or uncertain. Every title classified as relevant or uncertain triggered abstract evaluation. Once relevance was confirmed, the full article was reviewed. Later, a group of three reviewers, each of them working independently, selected all the articles that met the expected criteria. Extraction and analysis of each study were free from masking, and discrepancies were settled through common agreement.

Data extraction and managementThree investigators, working separately, extracted the data included as protocol variables, as well as the methodology used in every study in particular. Data were recorded in a specific Excel format and the statistical Kappa was calculated in order to evaluate inter-rater agreement.18 Discrepancies were solved through data review to reach common agreement. Data entry in RevMan 5.1 was done by one of the authors (VHGC), and no masking techniques were used.

Systematic review quality evaluationThe R-Amstar tool was implemented to evaluate the quality of the systematic review and support the confidence or wisdom of the recommendations derived from it. The tool was applied by two expert reviewers, one of them external to the study.

Evaluation of bias riskA group of three investigators, working separately, evaluated the risk of bias using a specific form, in accordance with the Cochrane criteria. The evaluation included: hypothesis, masking, randomization strategy, follow-up losses or dropouts, analysis, and sample size calculation.

In each case, scores were obtained according to the compliance percentage of the items evaluated in each of the strategies used for rating the quality of the clinical trial. The evaluation was done on the basis of the data published electronically in each case.

Treatment effect measurementFor continuous outcomes (visual analogue scale scores) the mean difference between the groups assessed was used; odds ratios (OR) were calculated for nominal dichotomous outcomes; and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were used for estimates.

Approach to unknown (publication) or lost dataWhen necessary, an attempt was made to contact the authors of the studies included in order to retrieve lost data. When this was not possible, they were calculated (in this particular case, standard deviation calculation from quartiles) and analyzed by sensitivity and study subgroup. If, despite this, it was still not possible to obtain lost data, the analysis was done using only the available data.

Heterogeneity evaluationThe evaluation was done using the methodological heterogeneity and/or clinical heterogeneity and/or graphic heterogeneity (forest plot), aside from the Cochrane I2 and Q statistics (Ji2).

Statistical heterogeneity was defined as the finding of a Cochrane Q (Ji2) of less than 0.1 or I2 greater than 50%.

Publication bias evaluationIt was based on a dual strategy involving the specific assessment of the study methodologies and/or the funnel plot analysis.

Summary of the dataThe free Cochrane Collaboration Review Manager (REvMan 5.1) was used. The quantitative analysis of the data was done per protocol. Difference means were used for continuous outcomes and their 95% CI was estimated; ORs were calculated for dichotomous data with their 95% CI, based on a random effects model for collective estimates.

Subgroup analysisIt was performed for all outcomes, differentiated by type of intervention (remifentanil group and epidural group) and by the risk of bias of the studies included in the analysis.

Sensitivity analysisSensitivity analyses focused on investigating the cause of the heterogeneity and the potential effect of the bias on the results.

ResultsThis systematic review was conducted of the world literature published until February 29, 2012, with a strategy open to the evaluation of experimental evidence capable of providing scientific support to propose recommendations on the use of remifentanil for the management of labour-associated pain.

By February 29, 2012, there were four active studies on remifentanil in the central clinical trial registry19; two of them assessed effectiveness, equivalence, and safety of the use of remifentanil vs. epidural analgesia for labour-associated pain, but they were not available at that time. (These are studies NCT00801047 and EUCTR2007-000808-32-NL.)

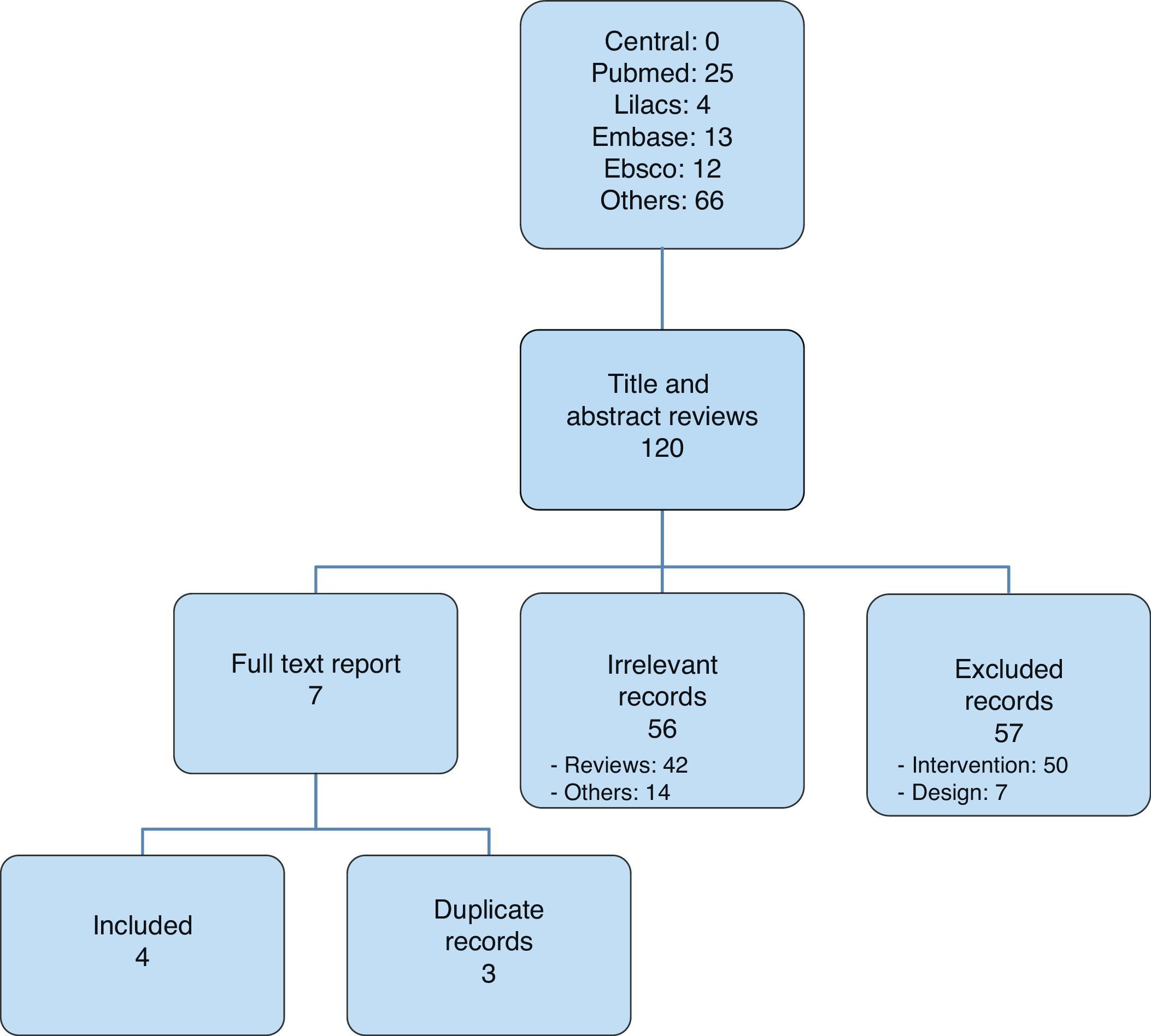

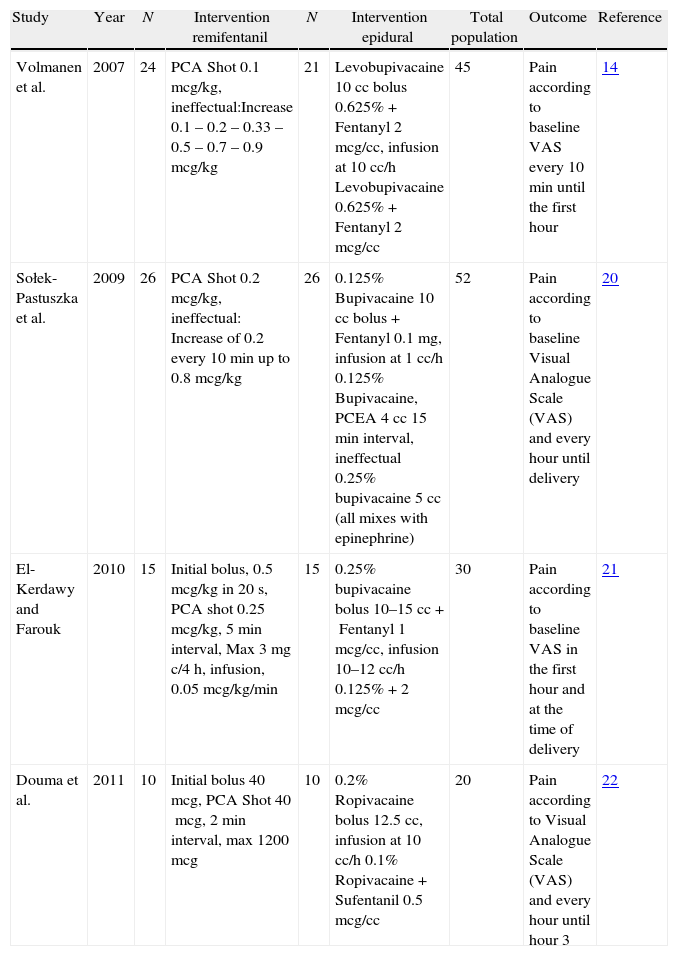

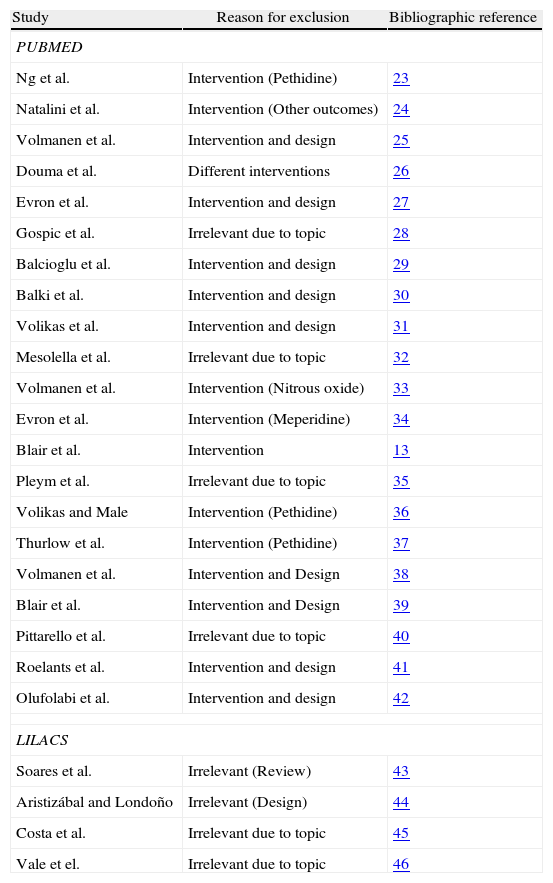

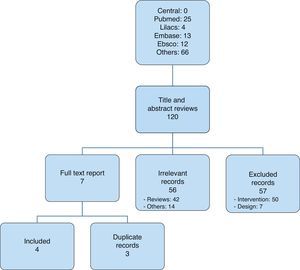

After selecting the articles for analysis14,20–22 (Fig. 1), those that were included were listed in Table 1; overall, 116 were excluded and Table 2 lists those that were not included in the analysis, corresponding to the Pubmed and Lilacs databases.13,23–46

Studies included.

| Study | Year | N | Intervention remifentanil | N | Intervention epidural | Total population | Outcome | Reference |

| Volmanen et al. | 2007 | 24 | PCA Shot 0.1mcg/kg, ineffectual:Increase 0.1 – 0.2 – 0.33 – 0.5 – 0.7 – 0.9mcg/kg | 21 | Levobupivacaine 10cc bolus 0.625%+Fentanyl 2mcg/cc, infusion at 10cc/h Levobupivacaine 0.625%+Fentanyl 2mcg/cc | 45 | Pain according to baseline VAS every 10min until the first hour | 14 |

| Sołek-Pastuszka et al. | 2009 | 26 | PCA Shot 0.2mcg/kg, ineffectual: Increase of 0.2 every 10min up to 0.8mcg/kg | 26 | 0.125% Bupivacaine 10cc bolus+Fentanyl 0.1mg, infusion at 1cc/h 0.125% Bupivacaine, PCEA 4cc 15min interval, ineffectual 0.25% bupivacaine 5cc (all mixes with epinephrine) | 52 | Pain according to baseline Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and every hour until delivery | 20 |

| El-Kerdawy and Farouk | 2010 | 15 | Initial bolus, 0.5mcg/kg in 20s, PCA shot 0.25mcg/kg, 5min interval, Max 3mg c/4h, infusion, 0.05mcg/kg/min | 15 | 0.25% bupivacaine bolus 10–15cc+Fentanyl 1mcg/cc, infusion 10–12cc/h 0.125%+2mcg/cc | 30 | Pain according to baseline VAS in the first hour and at the time of delivery | 21 |

| Douma et al. | 2011 | 10 | Initial bolus 40mcg, PCA Shot 40mcg, 2min interval, max 1200mcg | 10 | 0.2% Ropivacaine bolus 12.5cc, infusion at 10cc/h 0.1% Ropivacaine+Sufentanil 0.5mcg/cc | 20 | Pain according to Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and every hour until hour 3 | 22 |

Excluded studies (PUBMED and LILACS).

| Study | Reason for exclusion | Bibliographic reference |

| PUBMED | ||

| Ng et al. | Intervention (Pethidine) | 23 |

| Natalini et al. | Intervention (Other outcomes) | 24 |

| Volmanen et al. | Intervention and design | 25 |

| Douma et al. | Different interventions | 26 |

| Evron et al. | Intervention and design | 27 |

| Gospic et al. | Irrelevant due to topic | 28 |

| Balcioglu et al. | Intervention and design | 29 |

| Balki et al. | Intervention and design | 30 |

| Volikas et al. | Intervention and design | 31 |

| Mesolella et al. | Irrelevant due to topic | 32 |

| Volmanen et al. | Intervention (Nitrous oxide) | 33 |

| Evron et al. | Intervention (Meperidine) | 34 |

| Blair et al. | Intervention | 13 |

| Pleym et al. | Irrelevant due to topic | 35 |

| Volikas and Male | Intervention (Pethidine) | 36 |

| Thurlow et al. | Intervention (Pethidine) | 37 |

| Volmanen et al. | Intervention and Design | 38 |

| Blair et al. | Intervention and Design | 39 |

| Pittarello et al. | Irrelevant due to topic | 40 |

| Roelants et al. | Intervention and design | 41 |

| Olufolabi et al. | Intervention and design | 42 |

| LILACS | ||

| Soares et al. | Irrelevant (Review) | 43 |

| Aristizábal and Londoño | Irrelevant (Design) | 44 |

| Costa et al. | Irrelevant due to topic | 45 |

| Vale et el. | Irrelevant due to topic | 46 |

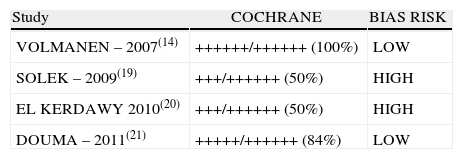

Two of the four studies included (inter-rater selection agreement, Kappa=1) (50%) were classified as “low bias risk” (Table 3).

Risk of Bias evaluated according to the Cochrane checklist for bias evaluation in Clinical Trials (Inter-rater agreement for Cochrane Criteria: Kappa=0.92).

| Study | COCHRANE | BIAS RISK |

| VOLMANEN – 2007(14) | ++++++/++++++ (100%) | LOW |

| SOLEK – 2009(19) | +++/++++++ (50%) | HIGH |

| EL KERDAWY 2010(20) | +++/++++++ (50%) | HIGH |

| DOUMA – 2011(21) | +++++/++++++ (84%) | LOW |

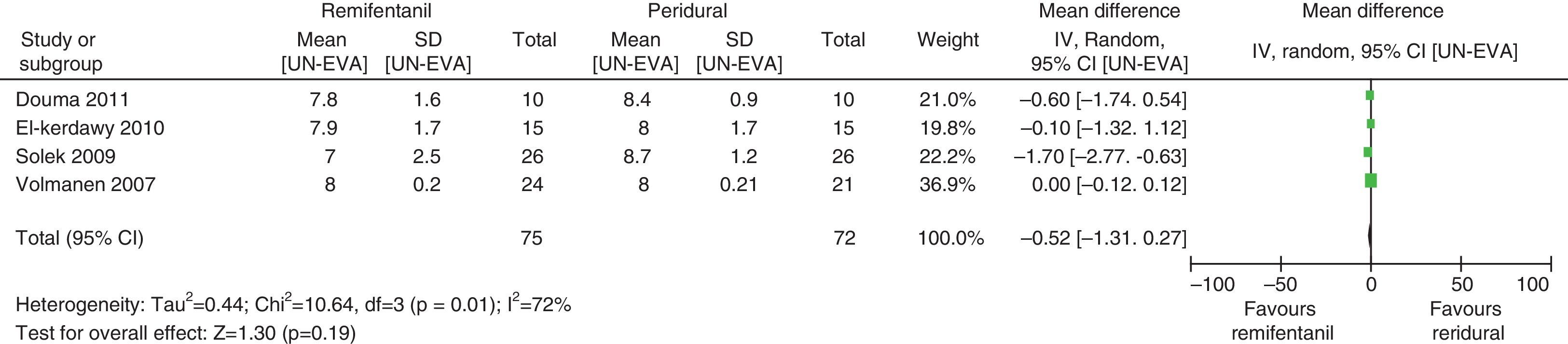

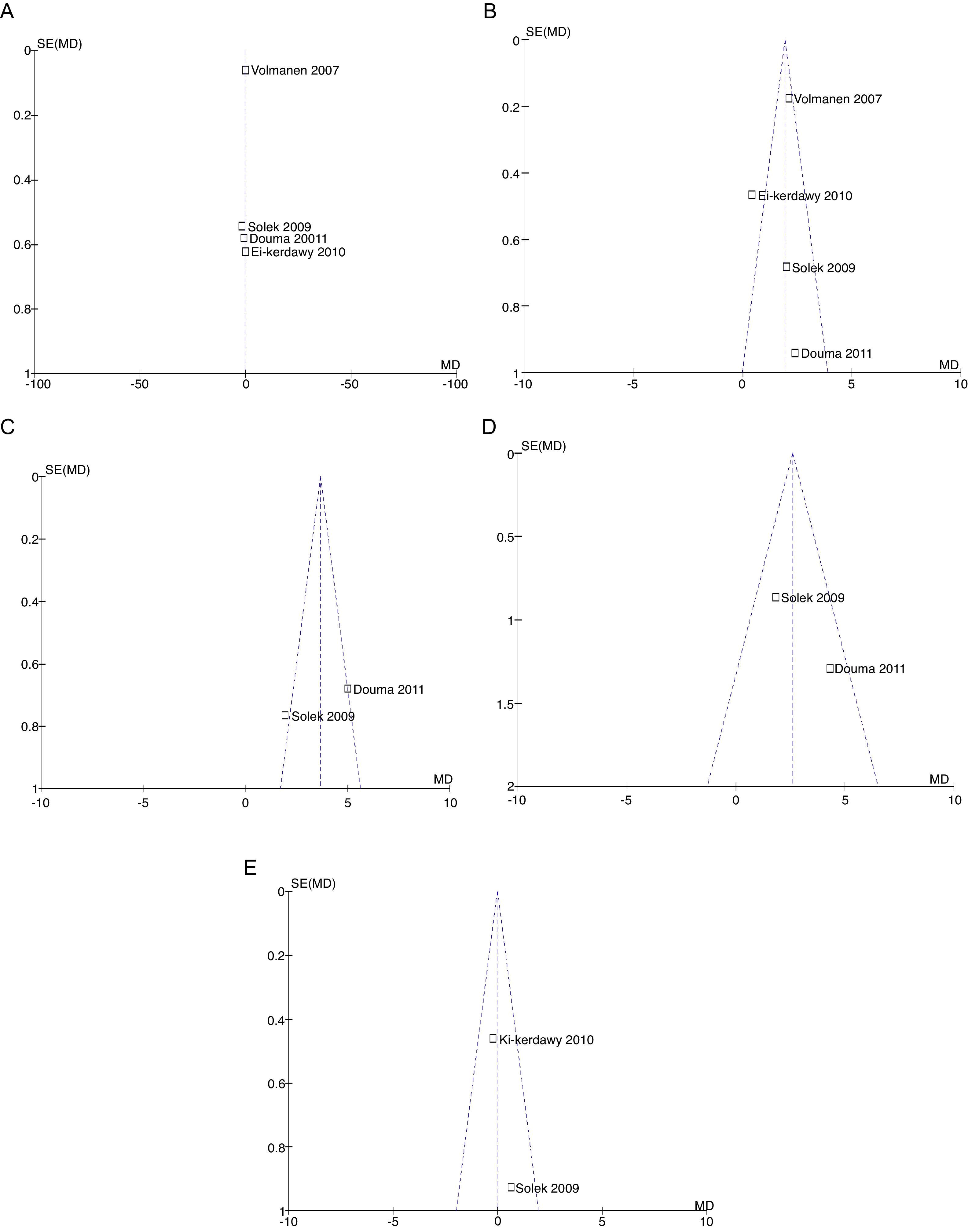

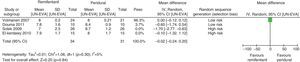

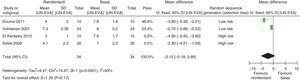

For equivalence evaluation, time analyses were performed in the studies evaluated of the intensity of pain in relation to baseline prior to the initiation of the specific analgesic therapy (remifentanil or epidural) in the two intervention groups (Figs. 2 and 3).

When the data of the four studies were analyzed at time point 0, important heterogeneity was found (I2=72% and Q−p=0.01). In the subgroup analysis, no heterogeneity was found for the studies with low bias probability (I2=5% and Q−p=0.3). When only the data of the studies with a high bias risk were considered, heterogeneity was observed (I2=73% and Q−p=0.05). None of the measurements showed statistical differences when comparing baseline pain levels (time 0), according to the p values for all the studies included, irrespective of the bias risk (p=0.19), studies with low bias risk (p=0.84), or studies with high bias risk (p=0.25).

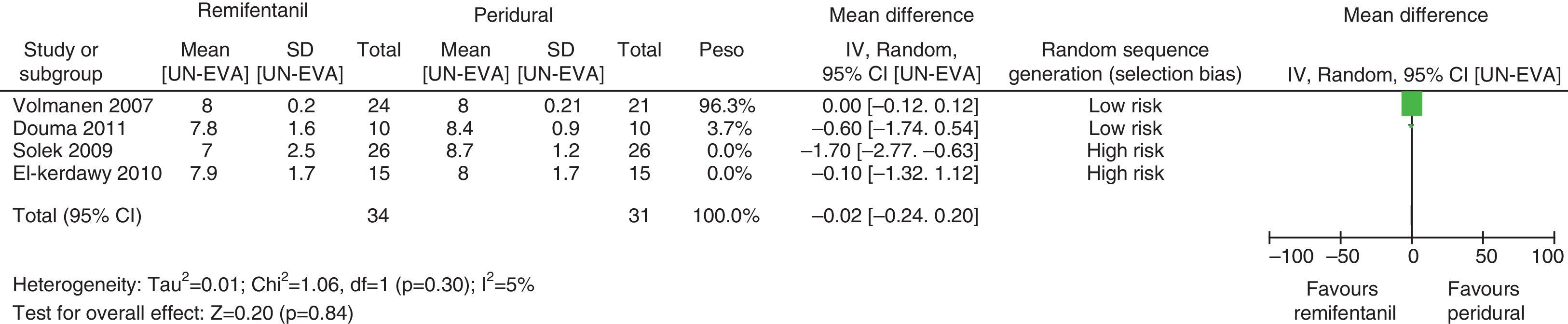

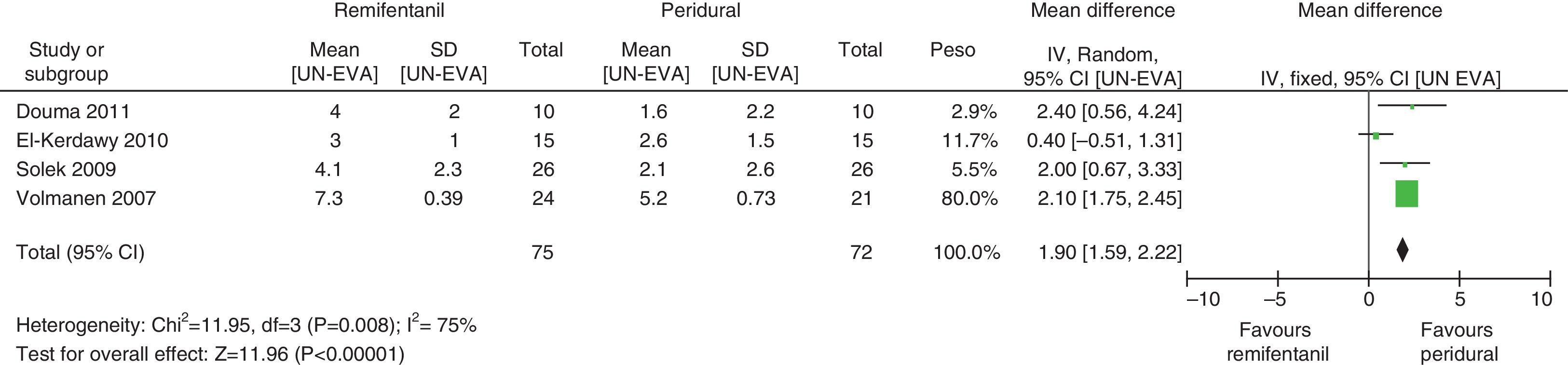

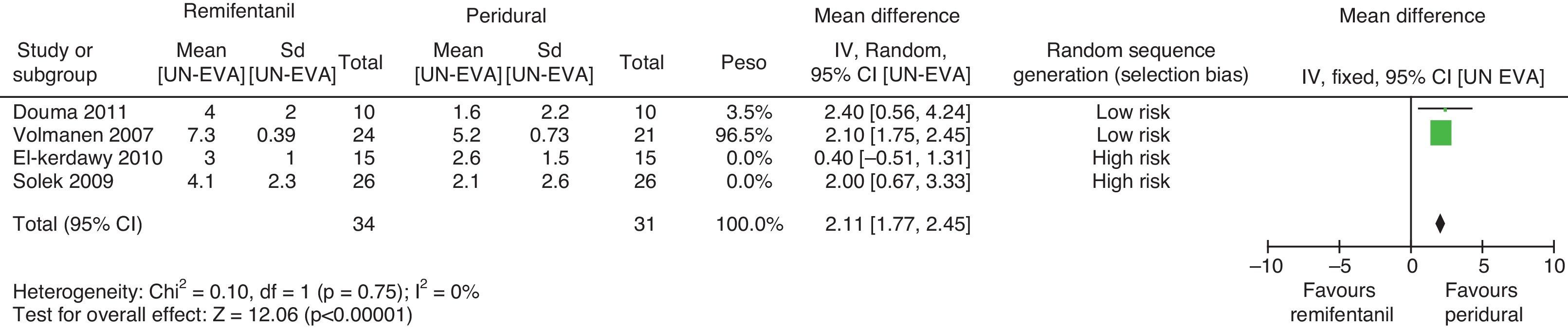

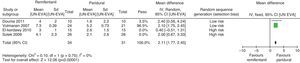

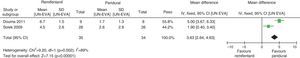

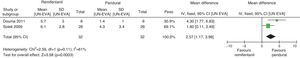

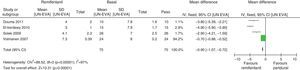

For pain measurements at 1, 2 and 3h (Figs. 4–7) heterogeneity was found when all the studies included in the analysis were examined (1h: I2=75% and Q−p=0.008; 2h: I2=89% and Q−p=0.002; 3h: I2=61%, but Q−p=0.11−disagreement against heterogeneity). In the subgroup analysis for the first hour, including only the studies with a low bias risk, no heterogeneity was observed (I2=0% and Q−p=0.75); there was an important difference in pain intensity between the two groups (mean difference=2.11; 95% CI 1.75 and 2.45 with p<0.00001 in favour of epidural analgesia).

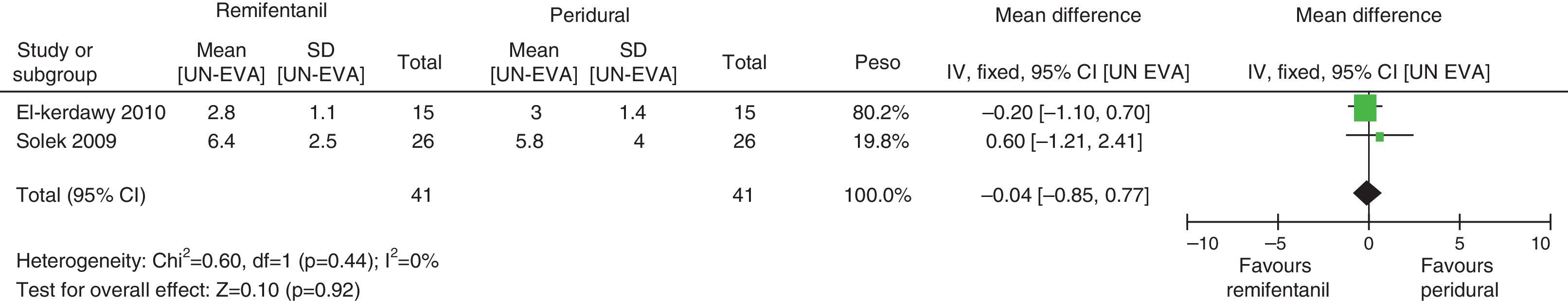

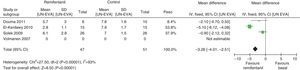

Absence of heterogeneity at the end of labour was confirmed (I2=0% and Q−p=0.44). When the differences in pain intensity were analyzed with both therapies at the time of delivery, no statistically significant differences were found (mean difference=−0.04; 95% CI −0.85 and 0.77, p=0.92) (see Fig. 8).

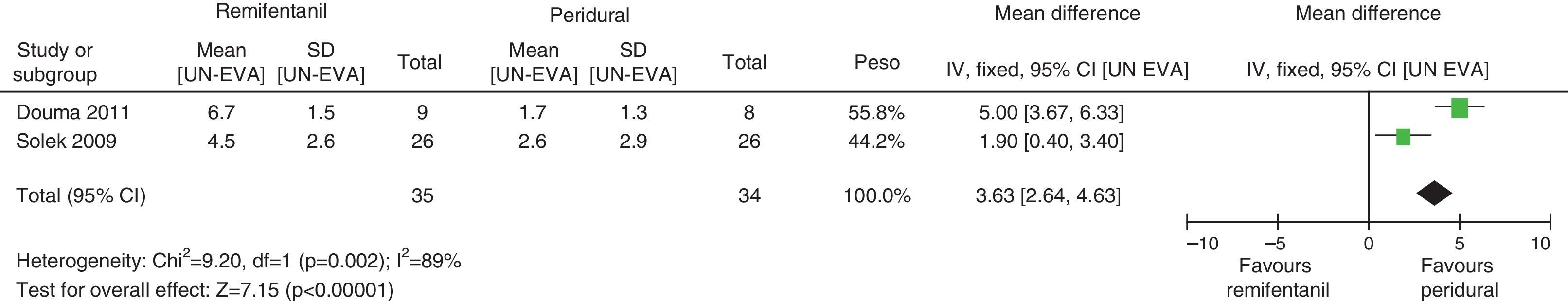

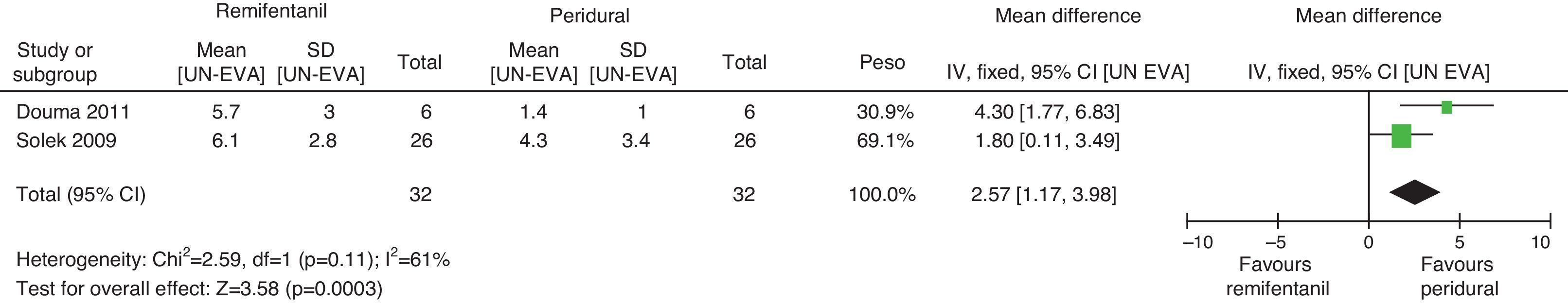

When the independent heterogeneity results were evaluated, an important statistical difference was apparent for the first 3h in favour of the use of epidural analgesia (mean difference at first hour: 1.9 (95% CI 1.5 and 2.22 p<0.00001); 2h: 3.63 (95% CI 2.64 and 4.63 p<0.00001); 3h: 2.57 (95% CI 1.17 and 2.45 p=0.0003).

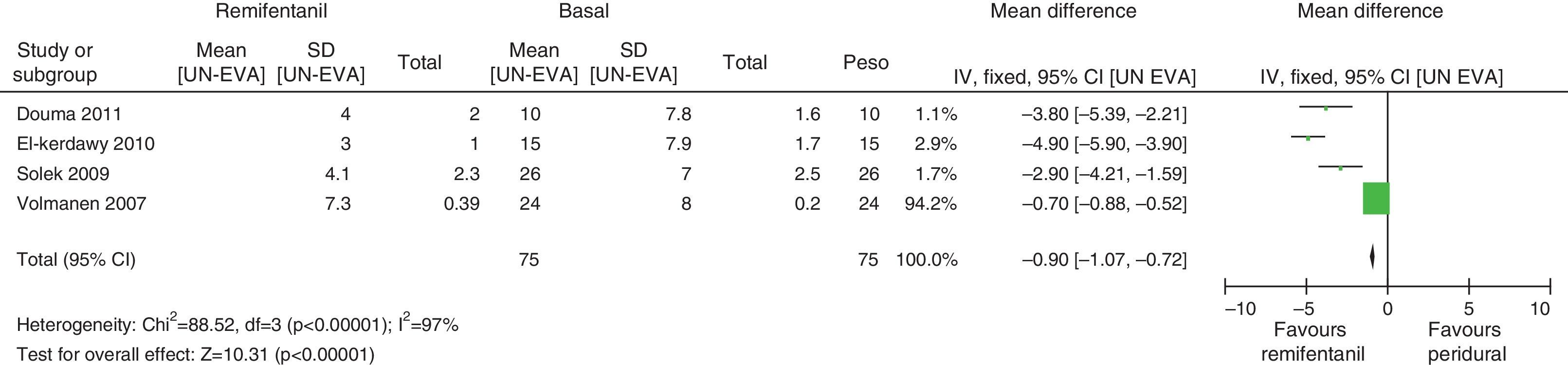

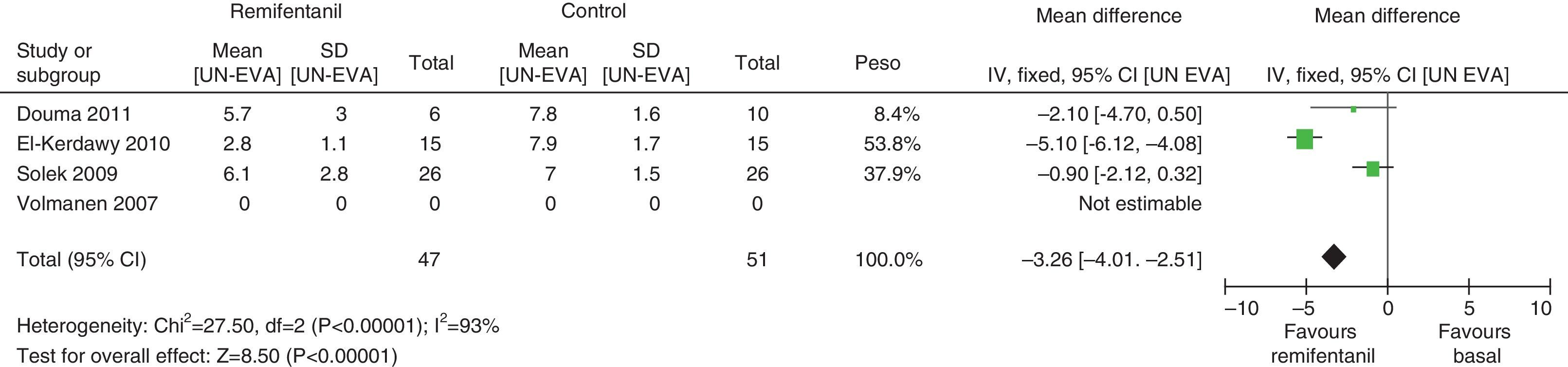

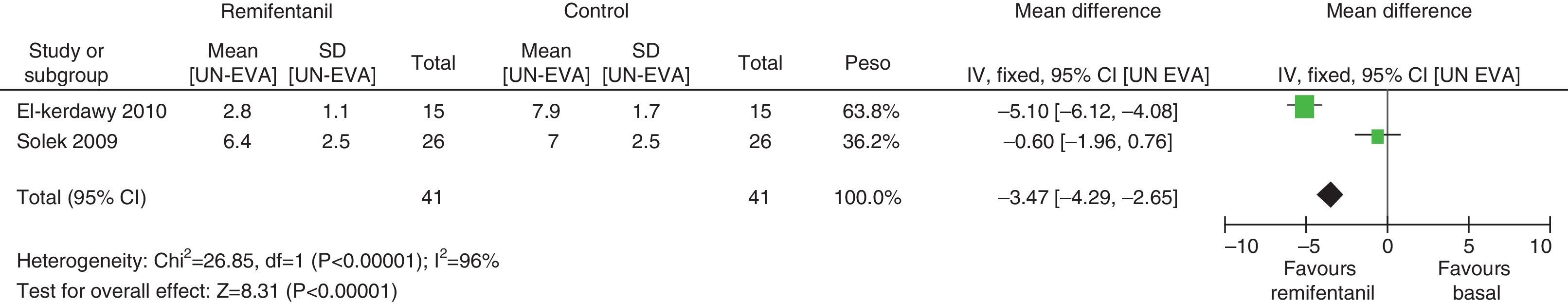

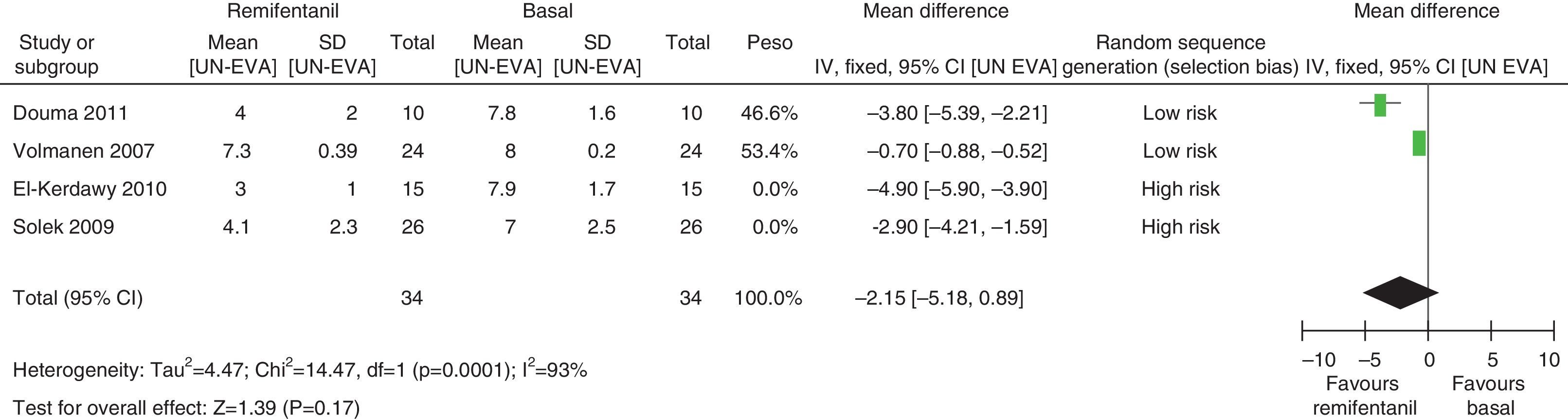

In assessing the efficacy of the treatment, pain intensity was analyzed at different points in time, using the pain level before the intervention (baseline) as control. Heterogeneity was confirmed when it was evaluated at different time points (remifentanil group for first hour: I2=97% and Q−p<0.00001; 3h 3: I2=93% and Q−p<0.0001; final time point: I2=96%, but Q−p<0.00001) (Figs. 9–11). With the subgroup analysis in the first hour for low bias risk studies, heterogeneity was also found (I2=93%, but Q−p=0.0001) (Fig. 12). Based on summary measurements of the four studies, despite the finding of heterogeneity, it is suggested that significant contrast was observed for mean pain differences, as follows: first hour: −0.9 (95% CI −1.07 and −0.72 p<0.00001); 3h: −3.26 (95% CI −4.01 and −2.51 p<0.00001) and final time point −3.47 (95% CI −4.29 and −2.65 p<0.00001).

In evaluating the incidence of adverse events associated with both interventions, we were able to isolate the investigation regarding outcomes of important medical interest. They were divided into those that compromise the newborn and those that compromise the woman in labour.

The maternal outcomes studied were: respiratory depression, sedation, nausea, instrumented delivery and caesarean section. The outcomes for the newborn were foetal bradycardia, Apgar and umbilical artery pH.

Neither of the groups showed abnormalities in foetal heart rate, Apgar score or umbilical artery pH. In some cases, the assessment of adverse events was discussed in the results and analysis section, as found within the normal range and with no differences between the two intervention groups. Those conclusions were based on the individual consideration of each article and not on a meta-analysis value as a result of this review.

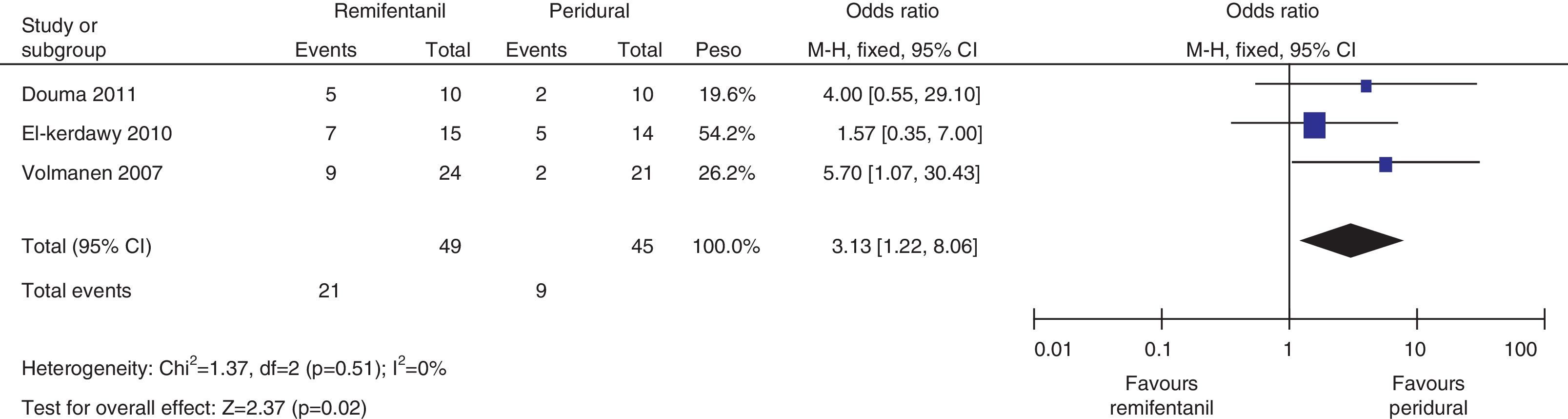

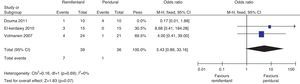

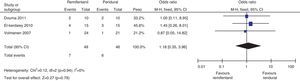

The mothers did not present important levels of respiratory depression or sedation; three of the four studies mentioned the number of mothers who experienced nausea, and the meta-analysis of the data (Q−p=0.51 and I2=0%) showed a higher incidence in the remifentanil group (21 vs. 9, p=0.02) (Fig. 13).

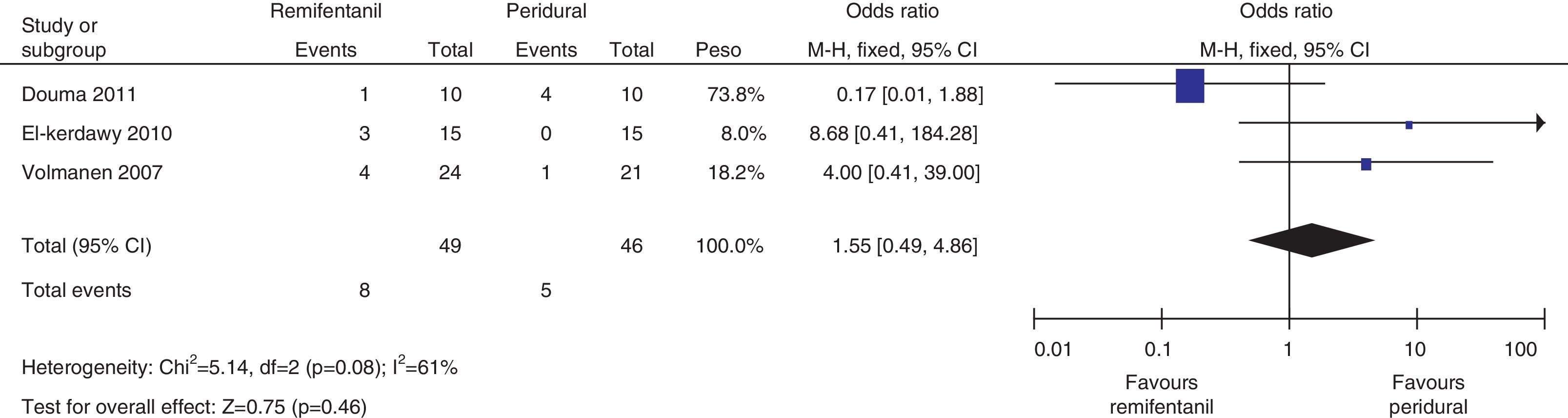

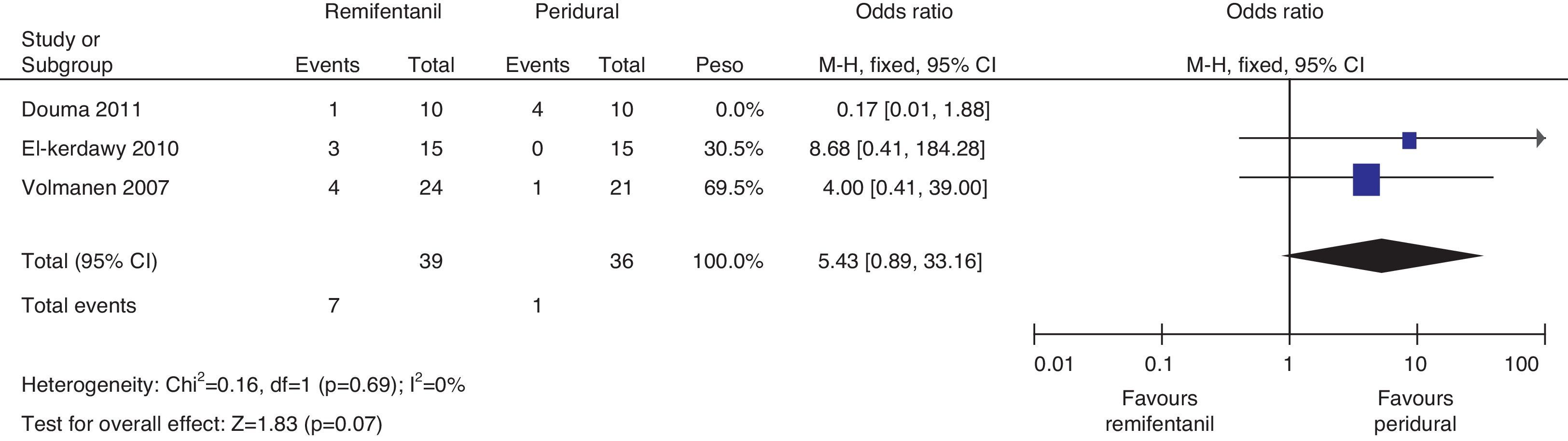

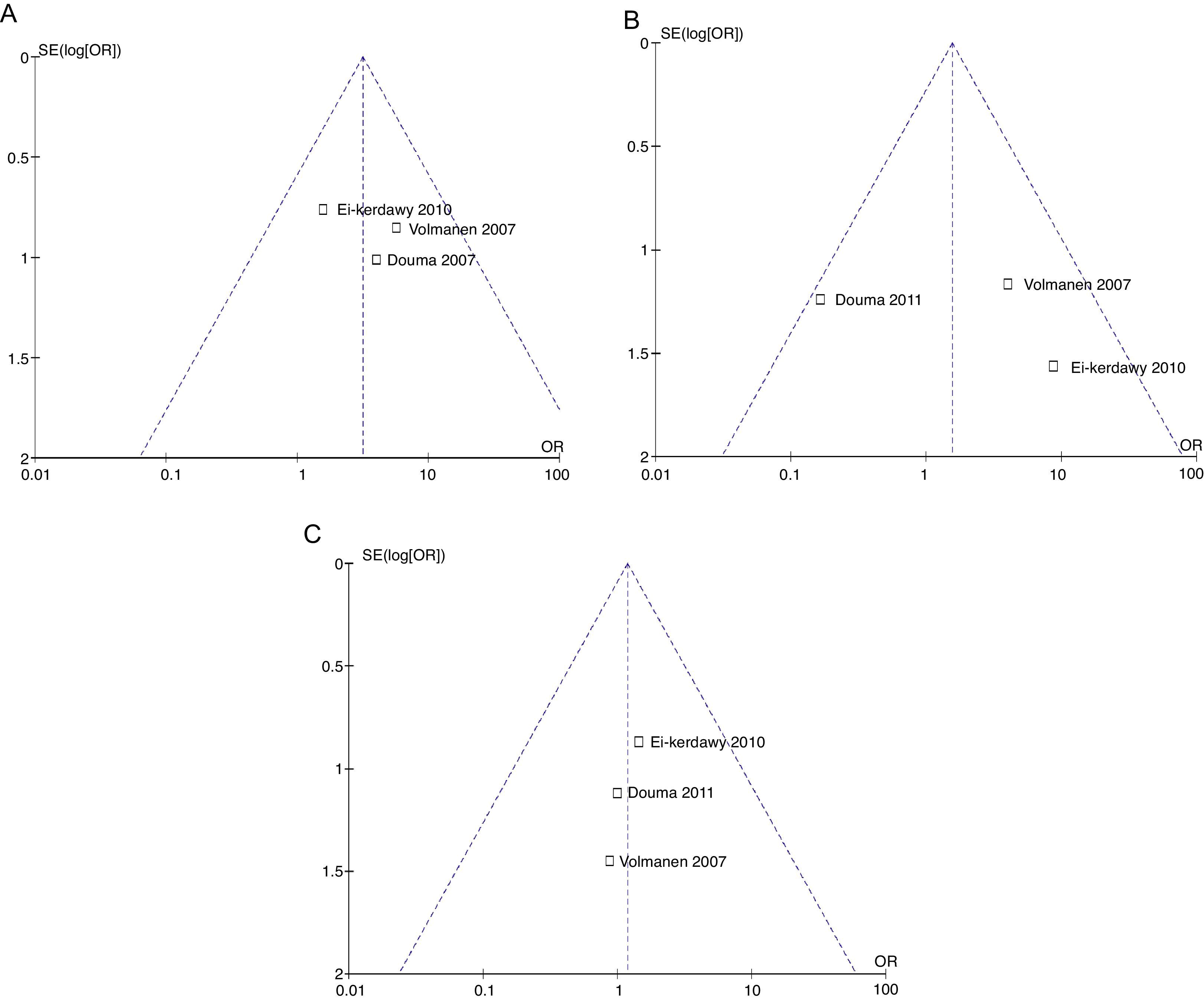

The analysis of the incidence of instrumented delivery, taking into consideration a borderline heterogeneity (Q−p=0.08 and I2=61%), found a similar trend (8 vs. 5, p=0.46). The subgroup analysis, excluding the study by Douma22 (due to a higher incidence in the epidural group) confirmed a not higher incidence of instrumentation in the remifentanil group, based on and OR of 5.43 (95% CI 0.89 and 33.16, p=0.07) and absence of heterogeneity (Q−p=0.69 and I2=0%). Those data were considered borderline and clinical analysis data (Figs. 14 and 15).

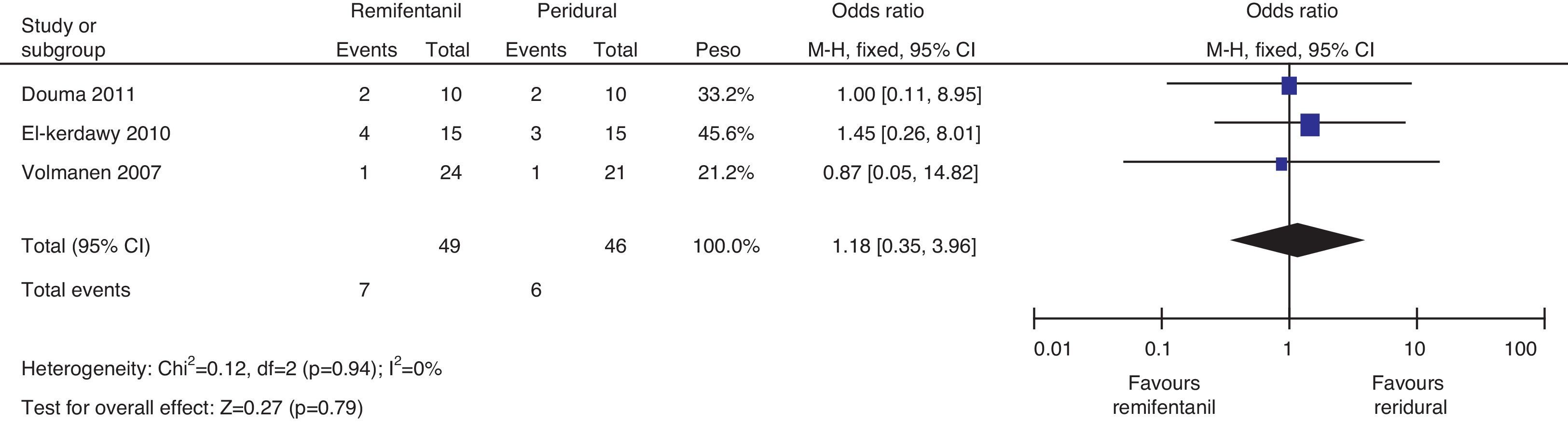

Regarding the incidence of caesarean section, following the heterogeneity analysis (Q−p=0.94 and I2=0%), no statistical difference was observed between the two groups (7 vs. 6, p=0.79) (Fig. 16).

Regarding satisfaction assessment, Douma22 does not show statistically significant differences between the comparison groups and when he evaluated 20 patients using a scale from 0 to 10 (where 0 is highly dissatisfied and 10 is highly satisfied), he found important values in hours 1, 2, 3 and in the final time point (remifentanil group: 8.6, 7.4, 7.3 and 8.0; epidural group: 8.3, 8.6, 7.3 and 8.3). In the study by Volmanen,14 satisfaction was based on a pain relief score from 0 to 4, were 0 was “no improvement” and 4 was “total improvement”. In that article, published values were 2.5 (2.2–2.9) vs. 2.8 (2.3–3.5) between the remifentanil group and the epidural group, with no statistically significant differences (p=0.11); scores of 2 and 3 were considered Moderate to Good pain relief. It is worth noting that neither intervention was rated as “complete improvement”. For El-Kerdawy, patient-rated satisfaction was 2.8 (±1) for the epidural group and 3.1 (±0.9) for remifentanil, with no statistically significant differences. In this study, satisfaction was assessed using a 1–4 scale that was described as ranging from poor to excellent, and a conclusion from the observations may be that both remifentanil as well as epidural analgesia correlated with good patient satisfaction with both treatments. This item was not assessed by Sołek-Pastuszka.20

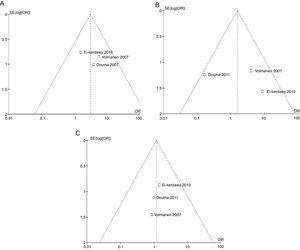

The probability of publication bias was evaluated for pain data points reported at different time points and it was found that there was low probability of bias derived from graphic symmetry in all items; bias probability for data reported at 2h is uncertain (Fig. 17). Likewise, the funnel plot was used to evaluate the probability of publication bias for the incidence of nausea, instrumented delivery and caesarean section, with the conclusion that there was low probability in the data shown in each study due to their symmetry (Figs. 17 and 18).

The R-Amstar was implemented by two reviewers working separately. A mean score of 41 was observed out of a total of 44, representing compliance with the Amstar standards of 93.18%, which categorizes this systematic review in the A ranking with high degree of confidence and clinical relevance for its recommendations.

DiscussionThe use of remifentanil resulted in significant pain reduction in each study. When the data were grouped together, it was impossible to arrive at a statistical conclusion about a summary number due to heterogeneity. Nonetheless, we found clinical pain reduction (3–4 points on the VAS) at different times in relation to time 0 of the intervention. Although prescription of control or placebo is ideal for this hypothesis, it is not ethical to withhold obstetric analgesia and, for that reason, the closest effectiveness measure was to study response to pain before and after the intervention.

When comparing remifentanil and epidural analgesia in terms of effectiveness, we suggest non-equivalence. We found marked effectiveness for epidural analgesia, although the analysis is limited by the heterogeneity of the data at certain times.

When remifentanil doses (0.2–0.9mcg/kg per PCA dose) were analyzed by sensitivity, no dose-efficacy correlation was shown that could modify the analgesic effect or the adverse events. Other studies that have analyzed the issue have demonstrated it with different doses (0.2–0.93mcg/kg/min) and similar analgesic efficacy.13,31,33,34,37–39

Remifentanil and epidural analgesia were equivalent at the end of delivery. This hypothesis may be based on incomplete epidural analgesic coverage due to the anatomy or the duration of the effect of the single dose used in some of the studies.

In the study by López-Millán et al.47 patients felt “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with the use of PCA with remifentanil; in this review, each study, using different scales, found an important correlation between remifentanil and good satisfaction, equivalent to that reported for epidural analgesia.

In terms of safety, we only found statistical differences for nausea, allowing us to conclude that remifentanil acts as a risk factor for nausea during labour. When analysing instrumented delivery, we concluded that the incidence in the remifentanil group was similar to that in the epidural group. We believe that the number of patients to treat must be larger in order to make a strong determination regarding remifentanil and this adverse event. We consider that the incidence and risk of caesarean section are similar as with epidural analgesia.

Neonatal respiratory depression is low when remifentanil is used during phase one of labour; in fact, Ross et al.48 showed a rapid washout in neonates undergoing elective surgery or diagnostic procedures, and several articles have reported increased neonatal bradycardia with remifentanil,31,49,50 but none of them report an association with important compromise of umbilical artery pH or abnormal APGAR test.

For this study, the probability of maternal or foetal complications is similar for patients treated with remifentanil or with epidural analgesia, which is consistent with what is published by Aristizábal and Londoño.44

Support for the management of non-surgical acute pain,51 opens the way for an alternative to conventional management of obstetric analgesia in our country. The idea of promoting its use with PCA when patients have contraindications for standard management suggests the need for clinical research in order to identify safe and effective doses. Our study contributes promising findings to the scientific community. Based on sound anaesthetic judgement, they point to the choice of an option that may be effective and safe during labour. We suggest that randomized controlled trials are needed, as well as the development of a sequential study of clinical trials in accordance with the recommendations from the group of Wetterslev et al.52

ConclusionBased on the results of this study, remifentanil for obstetric analgesia could be effective in the treatment of labour-associated pain, leading to a reduction of up to 5 points in the VAS in different trials and at specific time points. However, non-heterogeneous randomized controlled clinical trials are needed in order to confirm this hypothesis.

Remifentanil vs. epidural analgesia did not show equivalence on the basis of the statistical/or clinical analyses, although treatment efficacy was not discarded. In terms of safety, remifentanil showed the same therapeutic margin as epidural analgesia for the main expected maternal and foetal adverse events; the only measurement that showed increased incidence and risk was nausea. In view of this finding, if this option is considered for analgesia in labour, we recommend the application of the World Health Organization standards for prophylaxis and treatment of opioid-related nausea, as well as close mandatory monitoring in order to ensure best results.

We believe that satisfaction must be assessed using a universally adapted scale to avoid sensitivity-based analytical approaches, thus avoiding subjective challenges of an objective measurement that may polarize the use of remifentanil in labour.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of data. The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

FundingResearch Division and Fundación Universitaria de Ciencias de la Salud (FUCS) Medical School.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We thank the Anaesthesia Department at Hospital Infantil Universitario de San José, FUCS Research Division and School of Medicine; the reviewers for their great help with the application of the R-Amstar tool (Dr. Lisedt Ch. Duran R. – Hospital Universitario de la Samaritana Research Centre); and our families (CSAP).

Please cite this article as: González Cárdenas VH, González FDM, Barajas WJG, Cardona AM, Rosero BR, Manrique AJ. Remifentanil vs. analgesia Epidural para manejo del dolor agudo relacionado con el trabajo de parto. Revisión sistemática y meta-análisis. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2014;42:281–294.