Tuberculosis is an infectious disease that can compromise the success of kidney transplantation. The objective of the present study was to identify and assess the clinical and epidemiological differences of kidney transplantation subjects according to tuberculosis status in a Brazilian state.

MethodsThe records of 843 subjects were analyzed retrospectively in a case–control protocol. We performed crude and adjusted analyses according to tuberculosis diagnosis after kidney transplantation.

ResultsThe average age among subjects who underwent kidney transplantation were 40±14 years. Approximately 60% of the patients were males, and 57% were non-Caucasian. Tuberculosis was diagnosed in 13 kidney transplantation recipients (1.54%; 95% CI: 0.71–2.38%). The adjusted analysis revealed that patients with a history of tuberculosis were 41 times more likely to develop tuberculosis after kidney transplantation than were other patients (OR=40.71; 95% CI: 2.54–651.84). The number of infectious episodes (OR=1.35; 95% CI: 1.10–1.67) and the use of sirolimus during initial immunosuppression also increased this risk (OR=41.40; 95% CI: 2.59–660.31).

ConclusionThe implementation of follow-up screening and procedures is necessary to avoid compromising the effectiveness of kidney transplantation by developing diseases such as tuberculosis. Follow-ups are also important for the development of new technologies to improve the diagnosis and management of the disease in these patients.

La tuberculosis es una enfermedad infecciosa que puede comprometer el éxito del trasplante renal. El objetivo del presente estudio fue identificar y evaluar las diferencias clínicas y epidemiológicas de los sujetos con trasplante renal según el estado de la tuberculosis en un estado brasileño.

MétodosSe revisaron las historias de 843 pacientes. Se analizaron retrospectivamente en un protocolo de control de casos. Se realizaron análisis de datos brutos y ajustados de acuerdo con el diagnóstico de tuberculosis después del trasplante renal.

ResultadosLa edad promedio de los pacientes operados de trasplante renal fue de 40±14 años. Aproximadamente el 60% de los pacientes eran varones y el 57% eran no caucásicos. La tuberculosis se diagnosticó en 13 receptores de trasplante renal (1,54%, IC95%: 0,71–2,38%). El análisis ajustado reveló que los pacientes con antecedentes de tuberculosis tuvieron 41 veces más probabilidades de desarrollar la tuberculosis después del trasplante renal que otros pacientes (OR=40,71; IC 95%: 2,54–651,84). El número de episodios infecciosos (OR=1,35, IC del 95%: 1,10 a 1,67) y el uso de sirolimus en inmunosupresión inicial también aumentaron el riesgo (OR=41,40; IC95%: 2,59–660,31).

ConclusiónLa implementación de triajes y procedimientos de acompañamiento son necesarios para evitar el comprometimiento del transplante renal a causa de enfermedades como la tuberculosis. El seguimiento también es importante para el desarrollo de nuevas tecnologías que mejoren el diagnóstico y tratamiento de la enfermedad en estos pacientes.

The number of kidney transplantations (KTX) has increased in recent years, mainly due to a new environment where non-transmissible chronic diseases, including diabetes mellitus, obesity, and hypertension, represent a growing global public health issue.1–3 Nonetheless, the success of renal replacement therapy (RRT) can be compromised by the higher susceptibility of KTX recipients to infectious comorbidities in a context where certain transmissible diseases have not yet been controlled.1,3–5

Tuberculosis (TB) is one of those infectious diseases that can compromise KTX success. The relationship between these two conditions has been studied,6–9 and a recent meta-analysis demonstrates that the prevalence of TB in KTX patients may reach 83 times in the overall population.10 Immunosuppressant agents,11,12 previous RRT,13,14 and sociodemographic characteristics15 are associated with the coexistence of TB and KTX. However, the presence of comorbidities and other infectious diseases after KTX may have biased some analyses.13,16,17

The Brazilian National Transplantation Program is one of the largest transplant programs in the world and receives annual state funding of approximately 500 million dollars.18 The efforts aimed at the transplantation programs may nevertheless fall short of the intended success if transplant patients are not appropriately monitored and managed, particularly with respect to infectious diseases.

The aim of this study was to identify and assess the clinical and epidemiological differences among patients who underwent kidney transplantation according to TB illness status.

MethodsThe state of Espírito Santo (ES), located in southeastern Brazil, has an estimated population of 3,547,000 inhabitants.19 ES borders the state of Bahia, Minas Gerais, and Rio de Janeiro. The migration of people among these states is significant, due in part to patients seeking health care services. In the first trimester of 2012, ES performed 35.3 KTX per one million inhabitants. This was the 5th highest rate of transplantation among Brazilian states.20

There are currently five transplantation centers, and the records of 873 procedures were available for assessment and were retrospectively analyzed.

This is a case–control study where individuals who developed TB (TB) were cases and subjects who did not develop TB (non-TB) were controls. We chose to use data from all subjects who did not develop TB as controls because the database was previously structured, and our study did not involve any additional direct assessments. The use of non-TB patients as controls did not increase the statistical power.

A patient was considered to have TB if one or more of the following criteria were met: culture identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis; the presumptive diagnosis of TB, which required two positive bacilloscopy results; one positive bacilloscopy associated with a chest x-ray suggestive of TB; or histopathology with the presence of granuloma, with or without caseification necrosis in patients with a clinical suspicion of TB,21 with no change in diagnosis at the end of treatment.

The following sociodemographic variables were assessed: age (years); gender (male, female); skin color (white, non-white); years of education (<8 years, ≥8 years); marital status (married, not married); city of residence; and the type of residence (brickwork, wood, plaster, other).

Variables related to health were analyzed: presence of hypertension; diabetes; viral hepatitis; TB history prior to KTX; blood type (not AB, AB), cause of chronic renal disease (chronic glomerulonephritis, hypertension, diabetes, other, not determined, not assessed); and time of RRT (<1 year, ≥1 year).

The variables associated with transplantation were as follows: type of donor (alive, deceased); classification of the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) (identical, haploidentical, mismatched); presence of induction (administration of high doses of immunosuppressant agents during the period preceding KTX), pulse therapy (short and intensive administration of immunosuppressant agents), delayed graft function (DFG); number of infectious episodes; occurrence of bacterial infection, viral infection, parasitic infection, fungal infection; and use of cyclosporine, tacrolimus, sirolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, mycophenolate sodium, and azathioprine during the initial immunosuppression.

A crude analysis was performed to check the presence of association between the variables and the patient's TB status after KTX. Fisher's exact test was used for proportions, and Student's t-test was used for means. A significance level of 20% (p<0.20) was used. With the variables identified during the crude analysis, we performed an adjusted analysis for all factors included by logistic regression, adopting a significance level of 5% (p<0.05). These analyses were performed with Stata, version 12.0.

This study was approved by the Health Sciences Center Research Ethics Committee, Espírito Santo Federal University under number 204/10.

ResultsIn total, 873 KTX records were identified in five transplantation centers in the state of Espírito Santo, Brazil. The procedures were performed between 1980 and 2011, and 30 records were excluded because they referred to transplantations performed on the same subject. Therefore, 843 subjects who underwent KTX were included in the analysis.

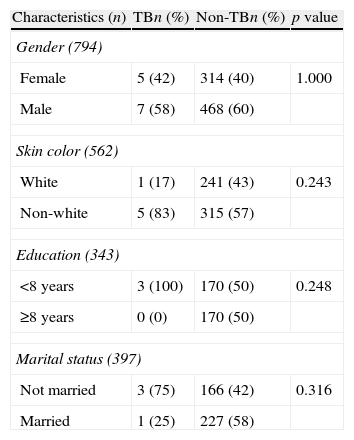

The average age of the KTX recipients was 40±14 years. Nearly 60% of the patients were male, and 57% were non-Caucasians. In this population, 58% of the patients were married, and 50% had <8 years of formal education (Table 1).

Distribution of sociodemographic characteristics of kidney transplantation patients in the state of Espírito Santo, Brazil, according to tuberculosis status.

| Characteristics (n) | TBn (%) | Non-TBn (%) | p value |

| Gender (794) | |||

| Female | 5 (42) | 314 (40) | 1.000 |

| Male | 7 (58) | 468 (60) | |

| Skin color (562) | |||

| White | 1 (17) | 241 (43) | 0.243 |

| Non-white | 5 (83) | 315 (57) | |

| Education (343) | |||

| <8 years | 3 (100) | 170 (50) | 0.248 |

| ≥8 years | 0 (0) | 170 (50) | |

| Marital status (397) | |||

| Not married | 3 (75) | 166 (42) | 0.316 |

| Married | 1 (25) | 227 (58) | |

TB was diagnosed in 13 of the 843 subjects in the study who underwent KTX (1.54%; 95% CI, 0.71–2.38).

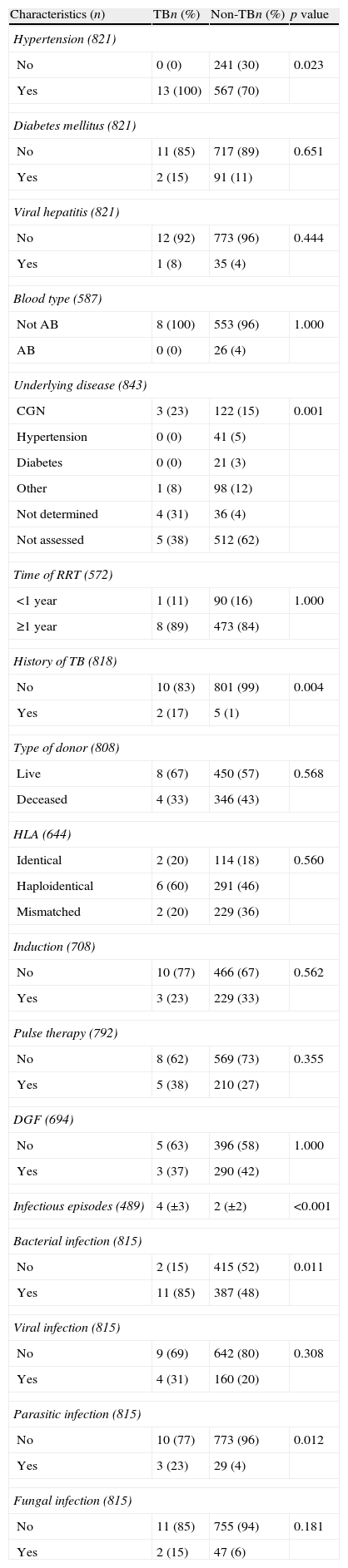

With respect to health history, the distribution of hypertension differed between TB and non-TB subjects (p=0.023). The proportion of subjects with a prior history of TB was higher in the group with TB after KTX (p=0.004), and these patients also suffered more infectious episodes (mean: 4±3) than did subjects in the non-TB group (mean: 2±2). The prevalence of bacterial infection (85% TB vs. 48% non-TB; p=0.011) and parasitic infection (23% TB vs. 4% non-TB; p=0.012) was higher in the TB group (Table 2).

Distribution of the health history characteristics of kidney transplantation subjects in the state of Espírito Santo, Brazil, according to tuberculosis status.

| Characteristics (n) | TBn (%) | Non-TBn (%) | p value |

| Hypertension (821) | |||

| No | 0 (0) | 241 (30) | 0.023 |

| Yes | 13 (100) | 567 (70) | |

| Diabetes mellitus (821) | |||

| No | 11 (85) | 717 (89) | 0.651 |

| Yes | 2 (15) | 91 (11) | |

| Viral hepatitis (821) | |||

| No | 12 (92) | 773 (96) | 0.444 |

| Yes | 1 (8) | 35 (4) | |

| Blood type (587) | |||

| Not AB | 8 (100) | 553 (96) | 1.000 |

| AB | 0 (0) | 26 (4) | |

| Underlying disease (843) | |||

| CGN | 3 (23) | 122 (15) | 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 0 (0) | 41 (5) | |

| Diabetes | 0 (0) | 21 (3) | |

| Other | 1 (8) | 98 (12) | |

| Not determined | 4 (31) | 36 (4) | |

| Not assessed | 5 (38) | 512 (62) | |

| Time of RRT (572) | |||

| <1 year | 1 (11) | 90 (16) | 1.000 |

| ≥1 year | 8 (89) | 473 (84) | |

| History of TB (818) | |||

| No | 10 (83) | 801 (99) | 0.004 |

| Yes | 2 (17) | 5 (1) | |

| Type of donor (808) | |||

| Live | 8 (67) | 450 (57) | 0.568 |

| Deceased | 4 (33) | 346 (43) | |

| HLA (644) | |||

| Identical | 2 (20) | 114 (18) | 0.560 |

| Haploidentical | 6 (60) | 291 (46) | |

| Mismatched | 2 (20) | 229 (36) | |

| Induction (708) | |||

| No | 10 (77) | 466 (67) | 0.562 |

| Yes | 3 (23) | 229 (33) | |

| Pulse therapy (792) | |||

| No | 8 (62) | 569 (73) | 0.355 |

| Yes | 5 (38) | 210 (27) | |

| DGF (694) | |||

| No | 5 (63) | 396 (58) | 1.000 |

| Yes | 3 (37) | 290 (42) | |

| Infectious episodes (489) | 4 (±3) | 2 (±2) | <0.001 |

| Bacterial infection (815) | |||

| No | 2 (15) | 415 (52) | 0.011 |

| Yes | 11 (85) | 387 (48) | |

| Viral infection (815) | |||

| No | 9 (69) | 642 (80) | 0.308 |

| Yes | 4 (31) | 160 (20) | |

| Parasitic infection (815) | |||

| No | 10 (77) | 773 (96) | 0.012 |

| Yes | 3 (23) | 29 (4) | |

| Fungal infection (815) | |||

| No | 11 (85) | 755 (94) | 0.181 |

| Yes | 2 (15) | 47 (6) | |

TB, tuberculosis; CGN, chronic glomerulonephritis; RRT, renal replacement therapy; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; DGF, delayed graft function; n, number of subjects in the sample.

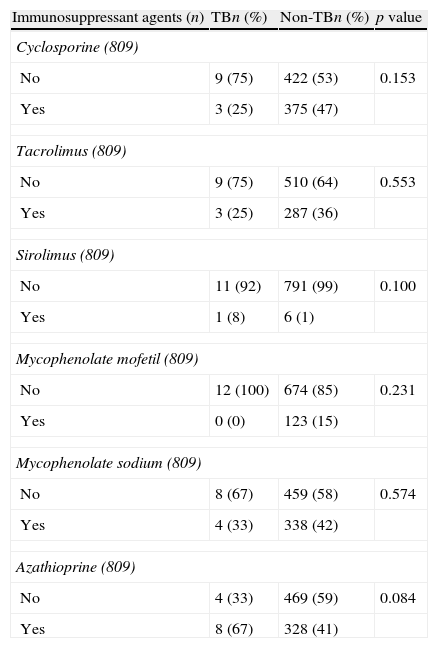

Table 3 presents study subjects according to the pharmacological therapy used in the initial immunosuppression. Sirolimus was the least frequently used agent (8% TB vs. 1% non-TB; p=0.100), and azathioprine was the most commonly used agent (67% TB vs. 41% non-TB; p=0.084).

Distribution of the initial immunosuppressant treatment agents of kidney transplantation subjects in the state of Espírito Santo, Brazil, according to tuberculosis status.

| Immunosuppressant agents (n) | TBn (%) | Non-TBn (%) | p value |

| Cyclosporine (809) | |||

| No | 9 (75) | 422 (53) | 0.153 |

| Yes | 3 (25) | 375 (47) | |

| Tacrolimus (809) | |||

| No | 9 (75) | 510 (64) | 0.553 |

| Yes | 3 (25) | 287 (36) | |

| Sirolimus (809) | |||

| No | 11 (92) | 791 (99) | 0.100 |

| Yes | 1 (8) | 6 (1) | |

| Mycophenolate mofetil (809) | |||

| No | 12 (100) | 674 (85) | 0.231 |

| Yes | 0 (0) | 123 (15) | |

| Mycophenolate sodium (809) | |||

| No | 8 (67) | 459 (58) | 0.574 |

| Yes | 4 (33) | 338 (42) | |

| Azathioprine (809) | |||

| No | 4 (33) | 469 (59) | 0.084 |

| Yes | 8 (67) | 328 (41) | |

TB, tuberculosis; n, number of subjects in the sample.

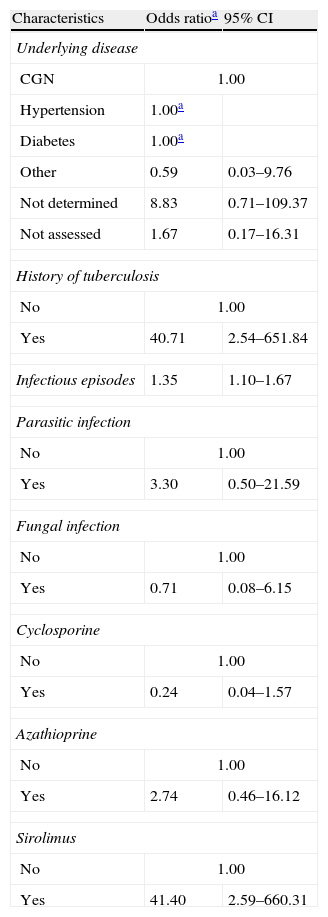

The following variables were included in the adjusted analysis: hypertension, underlying disease, history of TB, number of infectious episodes, bacterial infection, fungal infection, parasitic infection, and the use of cyclosporine, sirolimus, and azathioprine. When the regression model was applied, the variables hypertension and bacterial infection were omitted because they were perfect outcome predictors. Thus, the model was applied a second time after excluding these variables to provide an improved adjustment (Table 4).

Adjusted logistic regression analysis of the association between health history and tuberculosis in kidney transplantation subjects in the state of Espírito Santo, Brazil.

| Characteristics | Odds ratioa | 95% CI |

| Underlying disease | ||

| CGN | 1.00 | |

| Hypertension | 1.00a | |

| Diabetes | 1.00a | |

| Other | 0.59 | 0.03–9.76 |

| Not determined | 8.83 | 0.71–109.37 |

| Not assessed | 1.67 | 0.17–16.31 |

| History of tuberculosis | ||

| No | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 40.71 | 2.54–651.84 |

| Infectious episodes | 1.35 | 1.10–1.67 |

| Parasitic infection | ||

| No | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 3.30 | 0.50–21.59 |

| Fungal infection | ||

| No | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 0.71 | 0.08–6.15 |

| Cyclosporine | ||

| No | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 0.24 | 0.04–1.57 |

| Azathioprine | ||

| No | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 2.74 | 0.46–16.12 |

| Sirolimus | ||

| No | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 41.40 | 2.59–660.31 |

CI, confidence interval; CGN, chronic glomerulonephritis.

Subjects with a prior history of TB were more likely to develop TB following KTX (OR=40.71; 95% CI: 2.54–651.84). The risk of developing TB was also higher among subjects who used sirolimus as an initial immunosuppressant agent (OR=41.40; 95% CI: 2.59–660.31) and subjects who suffered more infectious episodes (OR=1.35; 95% CI 1.10–1.67). Subjects with hypertension or diabetes as underlying diseases exhibited a perfect outcome prediction and, therefore, did not have an odds value.

DiscussionIn this study, the prevalence of TB among subjects who underwent KTX (1.54%) was similar22,23 or lower24 than that reported by other Brazilian studies. However, the prevalence identified in our study was 40 times greater than the prevalence of TB within the total ES state population (0.036%).25 We also observed a higher prevalence of TB among subjects with a prior history of TB, those who experienced a higher number of infectious episodes, and those who used sirolimus as an initial immunosuppressant agent.

We believe that the study sample is representative of the KTX performed in ES. Our study findings should be considered because we have reason to believe that limitations from analyses deriving from secondary data, especially related to loss of information, did not interfere with the results.

Sociodemographic characteristics, which usually play a significant role in the presence of TB within the overall population, are also related to the development of TB in individuals with renal diseases.26,27 However, we did not observe significant differences in this study, although our study population represented a diverse group. A statistically significant difference was observed in the health history, which significantly contributed known and cumulative risk factors in subjects who underwent KTX. These risk factors include end-stage renal disease, diabetes, malnutrition, vitamin deficiency, and treatment with corticosteroids and other immunosuppressant agents.28

Protective immunity against M. tuberculosis is mediated by macrophages and T cells.28 The advanced immunosuppression associated with renal disease results in neutrophil functional abnormalities, monocyte and natural killer cell dysfunction, and reduction of T and B cell activity.29,30 The increased infection rates indicate that the adaptive response is weakened in this population.30 Thus, it is possible to note the relationship between number of infectious episodes and cases of bacterial and parasitic infections with TB development after KTX.

TB infection prior to KTX increased the risk of a new diagnosis of TB, 41-fold, in the study sample. This increase may be related to the reactivation of latent infections, which typically manifest earlier in the period following KTX when the doses of immunosuppressant agents are higher. The risk of TB in patients undergoing dialysis is 20 times that within the overall population.13,27 Reinfection, which has also been documented, should also be taken into account as a cause of recurrent TB,31 especially in countries with moderate to high loads of the disease, such as Brazil. A median of 4 years has been calculated from the time of the KTX to TB diagnosis in a study within the same population.32 Thus, in this population, the screening for latent TB during the period preceding KTX is essential to prevent the onset of the disease during the follow-up period. A systematic review has found evidence that prophylaxis with isoniazide should be considered for subjects undergoing KTX in TB risk areas.33

TB is an opportunistic disease and is therefore a disease of particular importance in an immunosuppressed population. A period shorter than six months after transplantation or an episode of rejection treated with pulse therapy has been reported as predictors of TB.34 The immunosuppressant agents tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil have also been associated with early development of TB during the period following KTX.27 However, this relationship with pulse therapy was not observed even in the crude analysis. Nonetheless, sirolimus, which is typically used as a second-line agent with a progressive increase in use during induction and maintenance immunosuppressant therapy due to its low nephrotoxicity compared to calcineurin inhibitors,35 was associated with a higher rate of TB, which suggests that more attention should be given to the safety profile of this immunosuppressant agent, despite the large confidence interval found in the study.

Important state investments have been made in the development and implementation of KTX in Brazil. The high rates of TB, a neglected disease, cause concern regarding the success of this treatment. Thus, to avoid the compromise of KTX success by diseases such as TB, it is necessary to implement screening procedures in the health services and to develop new technologies to improve the diagnosis and management of the disease in these patients.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.