Some scholars have highlighted the declining power of the G7 under the leadership of the US and the rising relevance of some underdeveloped countries grouped as “brics” (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), which has spearheaded a new hegemony: the creation of a new bank that will function as a development bank. This article aims to show whether or not a brics’ bank is desirable and doable. Our conclusions show that China is the only country among the brics with high growth, foreign international reserves, and current account surpluses. The creation of a new development bank, therefore, depends on China's will to finance other members.

Para algunos autores, el poder económico y político de los países más avanzados del mundo, liderados por los Estados Unidos, está declinando. Al mismo tiempo, algunos países subdesarrollados como Brasil, Rusia, India, China y Sudáfrica (llamados brics) han llamado la atención por la cantidad de reservas que poseen y porque podrían crear un nuevo orden internacional basado en una institución financiera que promueva el crecimiento: un banco de desarrollo. El objetivo de este artículo es mostrar si el establecimiento de este banco es deseable y realista. Nuestros resultados muestran que China es el único país de brics que tiene excedentes en la cuenta corriente, alto nivel de reservas y crecimiento económico; entonces, la decisión de establecer el banco depende de China.

The world economy changed after wwii. Keynes’ statement at Bretton Woods that underdeveloped countries “clearly have nothing to contribute and will merely encumber the ground” (quoted in Camara-Neto and Vernengo 2009, 200) was true at that time but perhaps the statementno longer holds. Economically and politically, several underdeveloped countries seem to be very important in today's world. However, does the economic and political weight of these underdeveloped countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, or brics)1 mean they can challenge the existing international world order established by the G7 (the us, Canada, Japan, France, Italy, Germany, and the uk) under the hegemony of the us?Can they initiate a new era of sustainable and high growth? Some scholars claim thatsuch situations are not possible for economic and political reasons. However, other scholars point out that brics can enforce a new international order and a new era of economic growth based on the creation of new financial institutions. Such a bank would function as a development bank (Stuenkel, 2013; Portal do Governo Brasileiro, 2014).

In this article, we are not concerned about whether or not brics can challenge the prevailing world international order. Rather, our objective is to shed some light on the feasibility of such a development bank to spur economic growth. After this introduction, in Section 2, we deal with the economic performance of both the G7 and brics from 1989 to 2012, and we highlight the outstanding increase of foreign exchange carried out by brics. In Section 3, we take into account whether or not a brics’ bank is desirable, and in Section 4 we consider whether or not this bank is doable, taking into consideration historical and political constraints the new bank may face. In Section 5, we present concluding remarks.

2Economic performance of G7 and brics and foreign reserve accumulation in bricsbrics’ increasing importance worldwide is based on (1) its population (42.3 percent of the world population in 2012), (2) its gdp level, and (3) its foreign exchange reserve level. In this section, we show the following: (1) the G7 and brics’ shares of world gdp at ppp2 (Purchasing Power Parity) from 1989 to 2012, and (2) growth rates and the levels of foreign exchange reserves for the G7 and brics.

Shares of world gdp have decreased in the G7 and increased in the brics. Figure 1 shows this phenomenon. However, we have to note that disparities exist through time and between the groups. First, for the G7, the share of world gdp remained constant at 50 percent from 1989 to 2000; thereafter, it decreased steadily. For brics, it can be seen in Figure 1 that the share of world gdp increased slowly from 1989 to 2000, with the pace accelerating from 2000 onwards.

Second, the evolution of each country differs in its respective group. For the G7 (see Figure 2), we can say that the importance in the overall share of world gdp has diminished for European countries (Germany, France, Italy, and the uk), that of Canada has remained quite constant, and the us exhibited an increasing share in the 1990s, but this share decreased sharply from the beginning of the 2000s onward. Meanwhile, for brics, South Africa seems unimportant (see Figure 3), due to its declining share in the world gdp. Russia has recovered from the 1990s’ collapse (due to oil and gas exports),3 but its economy is smaller than during the time of the former Soviet Union. Brazil's participation in overall gdp has decreased slightly from these levels of the 1990s and it is still a primary-export country. Therefore, gdp shares have increased in only two economies: India and China (see also May, 1993/94; Layne, 2009). China's gdp participation in the world total increased threefold in just 23 years and its value added in industry as a percent of gdp has increased from 41.3 percent to 46.5 percent from 1990 to 2011.

Likewise, with respect to their increasing shares of world gdp, brics augmented their level of foreign exchange reserves from 1989 to the present day. In 1989, brics accounted for 4 percent of the total foreign exchange reserves in the world; in 1999, their share of the total was 13.1 percent; and finally, in 2010, brics’ portion of the global reserve was 40.9 percent. In other words, brics’ share of the world total reserves has increased 10.2-fold in 21 years. Meanwhile, the G7 foreign exchange reserves have fallen continuously from 1989 onward: 43.2 percent out of the total in 1989, 29 percent in 1999, and 15.4 percent in 2010. However, a key point to highlight is that China's share in total brics’ reserves represented 73 percent in 2010; this means China holds 30 percent of the total international reserves. Brazil and Russia had increased the level of their reserves after the crisis in 1998, but with the 2007-08 crisis, their international reserves fell again.

On the one hand, the accumulation of international reserves has represented strength for underdeveloped countries because it has helped to either avert crisis or handle the dollar superiority in international markets (Rodrik, 2006; Palley, 2014; Lapavitsas, 2013; Labrinidis, 2014). On the other hand, the accumulation of international reserves has represented a cost, not only because of the spread differential between “the private sector's cost of short-term borrowing abroad and the yield that the Central Bank earns on its liquid foreign assets” (Rodrik 2005, 7), but also because the foreign exchange reserve could be used to increase the stock of capital or social spending (antipoverty programs).

Following this line of thought, some post-Keynesian scholars argue that as long as international reserves go beyond 5 or 6 percent of gdp, the surplus can be used to increase the stock of capital (Cruz, 2006), and subsequently foster economic growth. Post-Keynesian scholars also claim that capital controls and not the increase of foreign exchange reserve prevent the outflow of capital and exchange rate problems (Grabel, 2003; Cruz, 2006). Finally, Marxian scholars also think that international reserves may have uses beyond buying T-bills (Harris, 2009; Lapavitsas, 2013), and that the accumulation of international reserves is excessive.

3Is a brics’ bank desirable?Up to this point, we have highlighted the following: (1) shares of world gdp and foreign exchange reserves have increased in brics,(2) China accounts for the majority of these increases, and (3) existing drawbacks and advantages in holding foreign exchange reserves. Now, we examine brics cooperation, the creation of brics bank, what a development bank is, and development bank desirability.

Goldman Sachs researcher Jim O’Neill wrote a pioneering paper about brics’ economic relevance in 2001. He argued that China and India had larger economies than Italy and Canada, sothe former countries should have been invited to join the G7, and the latter should have been asked to leave. The consolidation of brics followed the shock of the 2008 crisis; according to Stuenkel (2011), brics gained terrain at that time in economic and political terms because members had regular meetings and to some extent coordinated their policies, thereby generating positive effects among them. Finally, the meetings resulted in the creation of a development bank in 2014. According to the Sixth brics Summit celebrated in Fortaleza, Brazil in 2014:

brics, as well as other emdcs [Emerging Markets Economies and Developing Countries], continue to face significant financing constraints to address infrastructure gaps and sustainable development needs. With this in mind, [they] are pleased to announce the signing of the Agreement establishing the New Development Bank (ndb), with the purpose of mobilizing resources for infrastructure and sustainable development projects in brics and other emerging and developing economies.

Therefore, brics's objective is to achieve growth with its own resources. Historically, according to an orthodox point of view, underdeveloped countries have lackedthe capital to finance infrastructure and development, and have to ask for foreign loans or attract foreign direct investment. This situation has led to a kind of dependency and to a vicious circle in growth because underdeveloped countries have had a myriad of problems with external debt or sudden outflow of capital. However, according to a heterodox point of view, underdeveloped countries have been capital-starved because either debt service payments or remittances on foreign direct investment have represented a heavy outflow of resources (Baran 1957: Prebish, 1970; Toussaint, 2008a, 200b), underdeveloped countries have capital because they send capital abroad. Especially since the East Asian crisis in 1997, underdeveloped countries have accumulated enormous amounts of international reserves, and they subsequently purchased T-bills. Instead of buying T-bills, these reserves may be used to increase the investment rate in brics, which has been stagnating in Brazil, South Africa, and Russia. India also needs a heavy investment infrastructure (see Figure 5).

Foreign reserve accumulation may obey an active decision to hoard money —in contrast to the problem of high capital mobility-- and subsequently may be assigned to key sectors in each country, such as manufacturing, agriculture, infrastructure, etc. Some notion of planned industrialization directed by the state has been highlighted by development economics and Latin American structuralism (see Gerschenkron 1962; Prebish, 1970; Sen, 1983; Bruck, 1998;Levy Yeyati et al., 2004; Hirschman, 2013). Therefore, the idea of a new bank may soundquite convenient as a means to foster growth and development.4 Now, we proceed to analyze what a development bank is in the economic literature.

Historically, three phases can be distinguished in development banking. In phase I a development bank as an “Investment Bank” was aEuropean phenomenon in the 19th century; Belgium, France, and Germany used development banks (investment banks) to catch up economically with England in the 19th century. During this period, banks invested in railroads, channels, and heavy industries (Diamond, 1957, 1981; Cameron, 1953, 1958, 1961, 1972; Gerschenkron 1962; Patrick, 1972; Tilly, 1972, 1992). Phase II, from the Great Depression-wwii to the early 1980; sawthe development bank as an industrial promoter. Underdeveloped (and some developed) countries created development banks in response to the need for establishing national policies to foster industrialization to promote growth and subsequently development. The Japan Development Bank (jdb), the KfW in Germany, the Industrial Development of Canada, the Korean Development Bank (kdb), the Nafinsa in Mexico, the Corfo in Chile, and the bndes in Brazil were established during this period. Also during this period, heavy industrial activities as well as agriculture, housing, infrastructure, education, etc. were the main targets (Aubey 1961; Curralero 1999; Amsden, 2001; Levy Yeyati et al., 2004; Guth, 2006). Finally, in phase III, a development bank focused on narrower objectives than in previous periods had sectors such as international trade and Small and Medium Enterprises (smes) as its targets. This is the period under neoliberalism when development banks could solve market imperfections in the capital markets (Curralero 1999; Amsden, 2001; Levy Yeyati et al., 2004; Guth, 2006; Lazzirini et al., 2012; Isidro Luna, 2013).

The historical differences among the three types of development banks can be addressed in terms of ownership, institutions that led growth (the market or the state), and the activities carried out: (1) Investment Banks were private ownership and profit-oriented, as opposed to the second historical phase in which development banks were government sponsored institutions; (2) phase III's development banks were mainly government-sponsored institutions but served only as a complement to the economy, which had to be led by the market; (3) in phases I and III, development banks shared the market-led economy but differed in the ownership and the activities supported (see Table 1).

Development Banks by Ownership, Institutional Framework, and Activities Supported.

| Phases | Ownership | Institution | Activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Private | Market | Infrastructure and heavy industry |

| II | Public | State | Infrastructure, heavy industry, agriculture, housing, etc |

| III | Public | Market | International trade and smes |

Even though development banks have existed for hundreds of years, it is still difficult to operationally define what a development is (Lazzarini et al., 2012). This difficulty is due to the time and the space in which each development bank operates. In this article, we define development according to the following characteristics (Diamond, 1957, 1981; Maug 1973; Ramirez 1987; Bruck, 1998: Arméndariz 1999; Guth, 2006; Lazzarini et al., 2012): (1) it is a financial intermediary, (2) it must have the goal of promoting development, and (3) it is mostly a government-sponsored institution. Thus, our definition of a development bank resembles that in the second period in the history of development banking: development banks with public financing playing a big role in the economies of their respective countries. With this definition, we proceed to analyze whether or not a development bank may spur growth during the current neoliberal era.

4brics’ bank feasibility: constraints to ponderCan a new development bank produce growth for its members, using its own resources in this neoliberal era? According to Rodrik (2004), markets and government forces must combine to diversify the economies of underdeveloped countries. This coordination revolves around two market failures, one of which arises because of information problems, and the other because of the need for high-scale investments in infrastructure. A development bank's role in this process is defined as:

Going from the pre-investment phase of a project to the investment stage requires a more sizable expenditure of resources, which must be financed somehow. Commercial banks are typically not good at this….Hence governments will need alternatives sources of finance. This may come in several different forms, depending on the available fiscal and bureaucratic resources. Some examples are: development banks (Rodrik, 2004, 26)

Therefore, a development bank can be distinguished by these combinations of forces: the market should lead the economy, and the state should be subordinated to the market. In Rodrik's point of view, industrial policy must be privately oriented, and development banks must correct market failures in building infrastructure. Despite the fact that Rodrik notes that underdeveloped countries operate under a different environment in neoliberalism than in the Golden Age of capitalism, he dismisses the effect of important variables such as financialization and class struggle. In our point of view, Polanyi provides a broader framework than Rodrik, by addressing the constraints and possibilities of spurring growth in the future. Polanyi (2014) states that the term economy may have two meanings: (1) a mean-end relationship, in which scarce resources have to be allocated to alternative uses. Supposed rationality leads to correct choices. The self-regulated market, wage-labor, and private property are institutions considered under this meaning; (2) the human being to nature and human to human relationship, in which economic activity is never institutionalized by economic institutions.

The first meaning is logical, and the economic system follows only its own rules; this can be called an autonomous economy. The second meaning is empirical, and the economic system is conditioned to politics, culture, religion, etc.; this is called a conditioned economy. According to this second meaning, no economic institutions are important because they can provide unity and stability to the economic activities. According to Polanyi, there was an attempt to establish an autonomous economy during most of the 19th century and in the beginning of the 20th with disastrous societal consequences because the self-regulated market led to the Great Depression. For him, an institution such as this would never again reign in economic policy; societies after wwii would always be opposed to the commodification of land and labor.

Therefore, contrary to the orthodox point of view, even during the major part of the history of capitalism –the mercantile and Golden Age era-- economies have been conditioned to other no economic institutions. However, neoliberalism has been characterized by an intensified process of commodification of nature and labor, and also has been the period of unrestrained financial markets. Thus, this scenario poses constraints to a development bank that plans to mobilize resources to build infrastructure and sustainable development projects. In our point of view, a development bank would face the following constraints:

First of all, the bank would face increased competition in capital markets. From wwii to the mid-1970s, the world economy grew steadily at a high growth rate. Not only developed countries but also undeveloped and socialist countries performed quite well. After the Great Depression and wwii, the us reconstructed Western Europe and Japan and also set conditions to strengthen the economies of its allies and increase the volume of trade in the world. The dollar was converted to gold, but other currencies were pegged to the dollar. In addition, capital controls were established, and interest rates remained low.

In this scenario, some advanced capitalist countries and undeveloped countries established national policies directed by the state to achieve growth using several tools, development banks being one of them. Even though wages and the volume of employment increased during this period, for advanced capitalist economies, improvements in the conditions of life for the majority of people were called for because the race was with socialist countries.

From the end of 1970s onwards, growth rates have slowed globally. Self-regulation has appeared above all in financial activities, eroding the framework established during the Golden Age of capitalism (Campbell and Bakir, 2012). According to Krippner (2011) and Lapavitas (2013), households, states, and typical industrial business carry out extensive financial activities today. Therefore, a question that must be answered is how a development bank can spur growth in a worldwide context dominated by finance.

Second, a development banks may: (1) serve as a tool for dominating other countries, (2) serve as a tool for financing no key sectors, and (3) function adequately only in specific periods of time according to historical, social, and economic conditions. First of all, for orthodox scholars, the World Bank has been the most important development bank throughout history. For such scholars, the World Bank was created because of the capital market failure during the Great Depression (Krueger, 1998). It was thought that the world capital market was imperfect and that international cooperation was needed to channel capital from rich countries to poor countries (Gavin and Rodrik, 1995; Stiglitz, 1999). The main idea was that loans granted from the World Bank to poor countries had to be at a lower interest rate than those prevailing in the market.

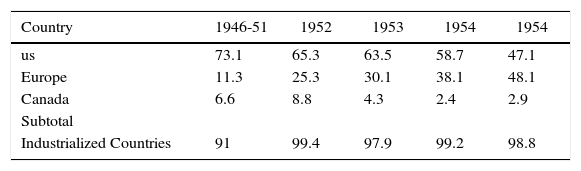

However, for heterodox scholars, the World Bank has never financed development. During its first years of operation, the World Bank financed only projects with a high-expected rate of profit in stable countries. Besides, as a resource for underdeveloped countries, the World Bank was meaningless because the main capital provider at the end of the 1940s and throughout the 1950s was the us with the Marshall Plan. When the World Bank did make loans to poor countries, those loans were very costly at a very high rate of interest and “relatively short period of repayment” (Toussaint, 2008, 21). In addition, frequently the majority of the money lent by the World Bank to poor countries was on the condition that the money had to be spent in developed countries (see Table 2).

Geographical Distribution of Expenditures Made with Funds Loaned by the World Bank, 1946-1955.

| Country | 1946-51 | 1952 | 1953 | 1954 | 1954 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| us | 73.1 | 65.3 | 63.5 | 58.7 | 47.1 |

| Europe | 11.3 | 25.3 | 30.1 | 38.1 | 48.1 |

| Canada | 6.6 | 8.8 | 4.3 | 2.4 | 2.9 |

| Subtotal | |||||

| Industrialized Countries | 91 | 99.4 | 97.9 | 99.2 | 98.8 |

Adapted from Toussaint (2008).

In the 1970s, according to Krueger (1998), the World Bank gained strength as a capital provider because the us entrusted to it the task of furnishing resources to poor countries. At the onset of granting resources to poor countries, the World Bank did not ask for any conditionality; however, with the international crisis during 1973/74 and the debt crisis in 1982, the World Bank spearheaded forcing poor countries towards neoliberalism, and we dare say that scarce development and inhibited growth have been the result. Therefore, both economic criteria and political criteria determine the performance of development banks.

A further example of unsuccessful multilateral development is regional banks. During the feeble discussion regarding the Bank of the South's5 (Banco del Sur) creation, some scholars such as Ocampo and Titelman (2009) argued that previous experiences of development banking had been successful in providing capital in Latin America. Ocampo and Titelman reviewed the Andean Development Corporation's (caf)6 case. The caf was created to support “the economic and social development of their member countries and focuses mainly on medium- and long-term lending, preferably in areas that would foster economic complementarities among the member countries” (Ocampo and Titelman, 2009, 251). In the 1990s and 2000s, caf has been the major capital provider of short-term and long-term loans for its members. However, caf resources have primarily financed the service and commercial sectors, which can barely spark economic growth. This situation represents a significant change in Latin America with respect to the period from 1940 to 1980, when development economics and structuralism proposed heavy industrialization through high investments led by the state as a way of catching up to the leading countries.

Finally, taking into account the experience of national development banks, banks such as Nafinsa in Mexico and bndes in Brazil were successful and unsuccessful during particular periods in their country's history. For example, Nafinsa, in Mexico, was the main capital provider to the industrial sector from wwii through the 1970s. Furthermore, Nafinsa not only built many of the basic industries in the country, such as the steel industry, but it also financed construction of very important infrastructure such as the university and the subway system. Another interesting example, along the same lines, is the bndes in Brazil. From 1952 through the 1970s, this bank helped to build the biggest industrial complex in Latin America (Curralero, 1998; Diniz, 2004; Guth, 2006). Both banks were models of development banking and extensively studied during that time. However, national development banks did not successfully promote growth during particular periods, as was the case for Nafinsa from 1982 onward, when it began to serve neoliberal purposes, being mostly a second-tier financial institution granting resources in the short-term to smes. The same could be said for bndes during the 1980s and the 1990s7 and Corfo in Chile (Carmona 2009).

Luna-Martinez and Vicente (2012) have contended that during the 1980s, development banks suffered from a major restructing, but they have been playing a counter cyclical role after the current crisis. However, their effect on growth is something that can be assessed only with the passage of time. Therefore, the lesson here is that national development banks could be good at promoting growth, depending on the national as well as the international context in which they are embedded.

Third, the only country that can finance another is China, assuming fiscal balance; it is a macroeconomic identity in an open economy in which the current account (CC) is the difference between savings (S) and investment (I):

Positive CC means that domestic savings are larger than domestic investments, so countries with surpluses can export capital. In contrast, if domestic savings are smaller than domestic investments, these countries have a deficit and capital has to be imported. Then, concisely, which of the brics’ countries have capital to be exported? Table 3 shows CC for all the brics from 1994 to 2013. As can be seen, only Russia and China have had persistent CC surpluses, with China as the most powerful country, as this article has shown. Does this mean that China is financing other members?

Current Account Balance. Percent of gdp: brics.

| Year | Brazil | China | India | Russia | South Africa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | −0.2 | 1.2 | −0.5 | 2.0 | 0.0 |

| 1995 | −2.4 | 0.2 | −1.6 | 1.8 | −1.6 |

| 1996 | −2.8 | 0.8 | −1.5 | 2.8 | −1.2 |

| 1997 | −3.5 | 3.9 | −0.7 | 0.0 | −1.5 |

| 1998 | −4.0 | 3.1 | −1.7 | 0.1 | −1.6 |

| 1999 | −4.3 | 1.9 | −0.7 | 12.6 | −0.5 |

| 2000 | −3.8 | 1.7 | −1.0 | 18.0 | −0.1 |

| 2001 | −4.2 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 11.1 | 0.3 |

| 2002 | −1.5 | 2.4 | 1.4 | 8.4 | 0.8 |

| 2003 | 0.8 | 2.8 | 1.5 | 8.2 | −1.0 |

| 2004 | 1.8 | 3.6 | 0.1 | 10.1 | −3.1 |

| 2005 | 1.6 | 5.9 | −1.2 | 11.1 | −3.4 |

| 2006 | 1.3 | 8.6 | −1.0 | 9.6 | −5.1 |

| 2007 | 0.1 | 10.1 | −0.6 | 6.0 | −6.7 |

| 2008 | −1.7 | 9.1 | −2.5 | 6.2 | −7.0 |

| 2009 | −1.5 | 5.2 | −1.9 | 4.0 | −3.8 |

| 2010 | −2.2 | 4 | −3.2 | 4.4 | −1.9 |

| 2011 | −2.2 | 1.9 | −3.4 | 5.1 | −2.3 |

| 2012 | −2.4 | 2.6 | −5.0 | 3.5 | −5.0 |

| 2013 | −3.6 | 2.0 | −2.6 | 1.6 | −5.6 |

Source: World Bank 2013.

China has to make an economic and political decision whether to finance underdeveloped countries or the us. Glosny (2010) argues that China wants to cooperate with the us; meanwhile, Stuenkel believes that brics want to challenge the us. The two previously mentioned positions are summarized in Figure 5 based on the theory of global imbalances. The us is the largest consumer in the world, and China directs Foreign Direct Investment to the us. China pursues an export-oriented model based on low wages and an undervalued exchange rate. Other brics’ members have very weak domestic markets and offer a very low rate of investment. Then, is China really industrializing other poor countries (being itself poor) or does it just want an exit to their products granting commercial credit? Can China influence the policy of the consumer of last resort carried out by the us?

Fourth, it is worth noting that nothing is known about how this new bank will make decisions, which countries will benefit the most, how this bank will avoid committing other policy-makers’ vices such as corruption,8 or how citizens will participate in determining the policies of this bank, etc. For example, Willis (1995) has reported that bndes had near total autonomy from political interests, but Diniz (2004) has argued that bndes has been a tool for the Brazilian ruling classes, and in the same vein, Lazzirini et al. (2012) have asserted that bndes disbursement from 2000s onwards has benefited some of Brazil's most prominent politicians.

5ConclusionWe have seen in this article that, first, shares of world gdp at ppp are declining for the G7 and increasing for brics, but China and India account for the majority of this increase. Similarly, foreign exchange reserves have increased in brics but China is the only important country. Second, a brics’ bank may be desirable as a means of allocating capital from rich countries to the poor; however, past experiences have shown that development banks are not good at promoting development because either they are an instrument of domination or they do not support priority sectors. In this case, development banks can promote economic growth restricted to the national and international context in which they operate. How can we avoid repeating this mistake? That is an unanswered question for proponents of brics’ development bank.

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (unam) e Instituto Politécnico Nacional.

Some scholars use brics to refer to four countries only: Brazil, Russia, India, and China. We include South Africa and thus “brics.”

Making comparisons among countries at gdp at ppp can cause some problems depending on the bundle that is used. If this bundle is too basic, underdeveloped countries’ gdp will be overestimated because prices of nontradeable goods are cheaper than in the developed countries.

For the Russian strategy of growth during the last 12 years, see Harris (2009).

Bresser-Pereira and Galo argue that perfect allocation of capital is always impossible because the inflow of capital provokes exchange rate appreciation and a subsequent loss of competitiveness.

From 2003 to 2007, some Latin American countries had current account surpluses and a notable increase of foreign exchange reserves that almost matched the arrival of left wing governments. This situation gave rise to the idea of the Banco del Sur, which was created on September 26, 2009. The presidents of Brazil, Argentina, Venezuela, Ecuador, Bolivia, Uruguay, and Paraguay signed an agreement establishing the bank with an initial capital of $20 billion. However, since that date, the bank has not yet started operation.

caf's original members were Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru; currently the country members are Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Portugal, Spain, Trinidad and Tobago, Uruguay, and Venezuela.

However, from 2002 onward, bndes has been very active in trying to promote growth.

During the discussion about the Banco del Sur, one of the reasons for favoring a new regional development bank apart from the distribution of pooled regional funds was as a regulator for each national development bank that received funds. According to Marshall and Rochon (2009, 189 and 190), the new development bank will take care of the “Achilles’ heel” of the Latin American public banks, which is corruption. However, what these authors did not mention is how the new bank will avoid committing this error.