Due to the “big five” challenges in the 21st Century related to the terms of energy, food, water, mobility and climate, mankind has to replace energy from fossil fuels step by step by renewable energies. Between them, solar energy is definitely the most abundant and clean. This is a major, but not the only reason for the inclusion of photoprocesses into chemical education. In this article we present an experimental approach to the basic concept suitable for teaching all phenomena involving light in a reasonable approximation. Updated experiments demonstrating the down conversion of light by fluorescence and room-temperature phosphorescence as well as aggregation induced emission and rigidification induced luminescence are described. In order to use these experiments for teaching basic concepts in photochemistry, a simple version of an energy level model, and an extended version, containing vibrational states, are proposed.

Debido a los «cinco grandes» retos del sigloXXI en relación con los términos de energía, alimentos, agua, movilidad y clima, la humanidad tiene que sustituir la energía de combustibles fósiles por las energías renovables paso a paso. Entre ellas, la energía solar es, sin ninguna duda, la más abundante y limpia. Esta es una razón importante, pero no la única, para la inclusión de los fotoprocesos en la enseñanza de la química. En este artículo se presenta un enfoque experimental del concepto básico adecuado para la enseñanza de todos los fenómenos relacionados con la luz en una aproximación razonable. Se describen experimentos actualizados que muestran la conversión descendente de la luz por fluorescencia y fosforescencia a temperatura ambiente, así como la emisión inducida por la agregación y la luminiscencia inducida por la rigidificación. Con el fin de utilizar estos experimentos en la enseñanza de conceptos básicos en fotoquímica, se proponen una versión sencilla de un modelo de nivel de energía y una versión extendida, que contienen los estados vibracionales.

Light-involving phenomena are most suitable for the communication of core concepts in natural sciences in close combination with everyday experiences of students as well as with innovative technological applications. In this sense a series of teaching materials have been developed. Several of them are available online in English for free on our website (http://www.chemiedidaktik.uni-wuppertal.de; Chemie und ihre Didaktik, 2016a, 2016b) by clicking “Flash Animations” or “Teaching Photochemistry” respectively, further have been published in this Journal and others (Tausch, 2005; Tausch, Banerji, Scherf, 2013; Tausch & Bohrmann, 2003; Tausch, Bohrmann-Linde, Ibanez, et al., 2013; Tausch & Korn, 2001). Recent and good introductory texts regarding the importance of photochemistry, basic concepts and actual topics have been published by Bach (2015), Balzani, Bergamini, and Ceroni (2015), and Bléger and Hecht (2015).

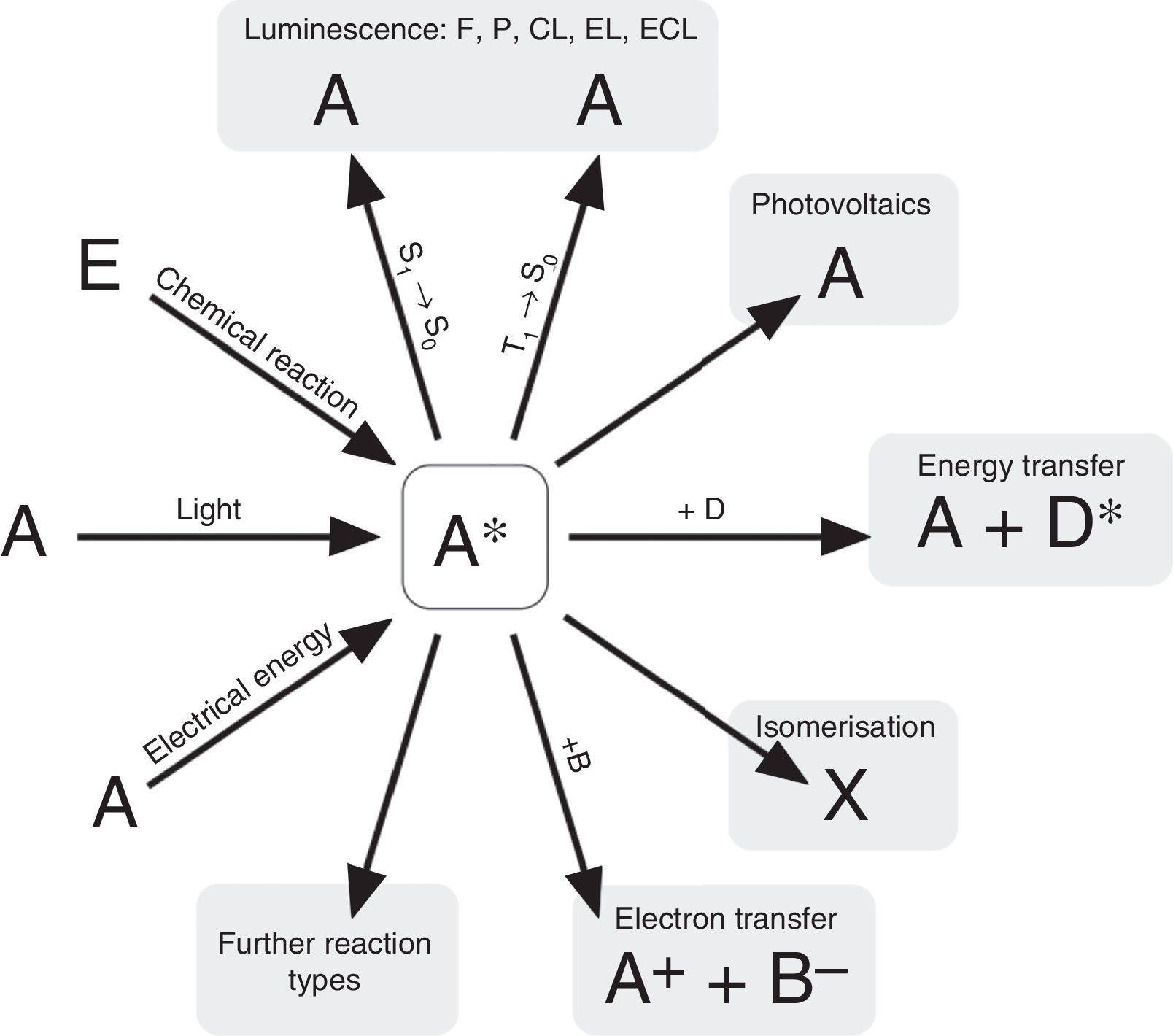

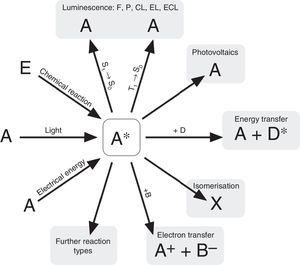

According to N. J. Turro's paradigm of the “excited states of molecules” as “the heart of all photoprocesses” and the interpretation of the excited state as “an electronic isomer of the ground state” (Turro, 1978), it should be emphasized that the excited state A* of a molecule A is not necessarily generated by light irradiation. It can also emerge from an exergonic chemical reaction or by supplying electrical energy (Fig. 1).

Generation and deactivation paths of the electronically excited state A* (F: Fluorescence, P: Phosphorescence, CL: Chemiluminescence, EL: Electroluminescence, ECL: Electrochemoluminescence, S1: 1st electronically excited singlet state, S0: singlet ground state, T1: 1st excited triplet state, D: Molecule of a compound D involved in energy transfer, B: Molecule of a compound B, involved in electron transfer, E: molecule of a starting compound E in a chemiluminescent reaction).

Actually, the excited state A* can deactivate or react in very different ways as well. Therefore a veritable zoo of photoprocesses results from the different deactivation routes of A* (Fig. 1). Traditionally some of them are allocated mainly to physics (i.e. photo- and electroluminescence). However, if one agrees with Turro that A* is an electronic isomer of A, all photoprocesses have to be considered as photochemistry.

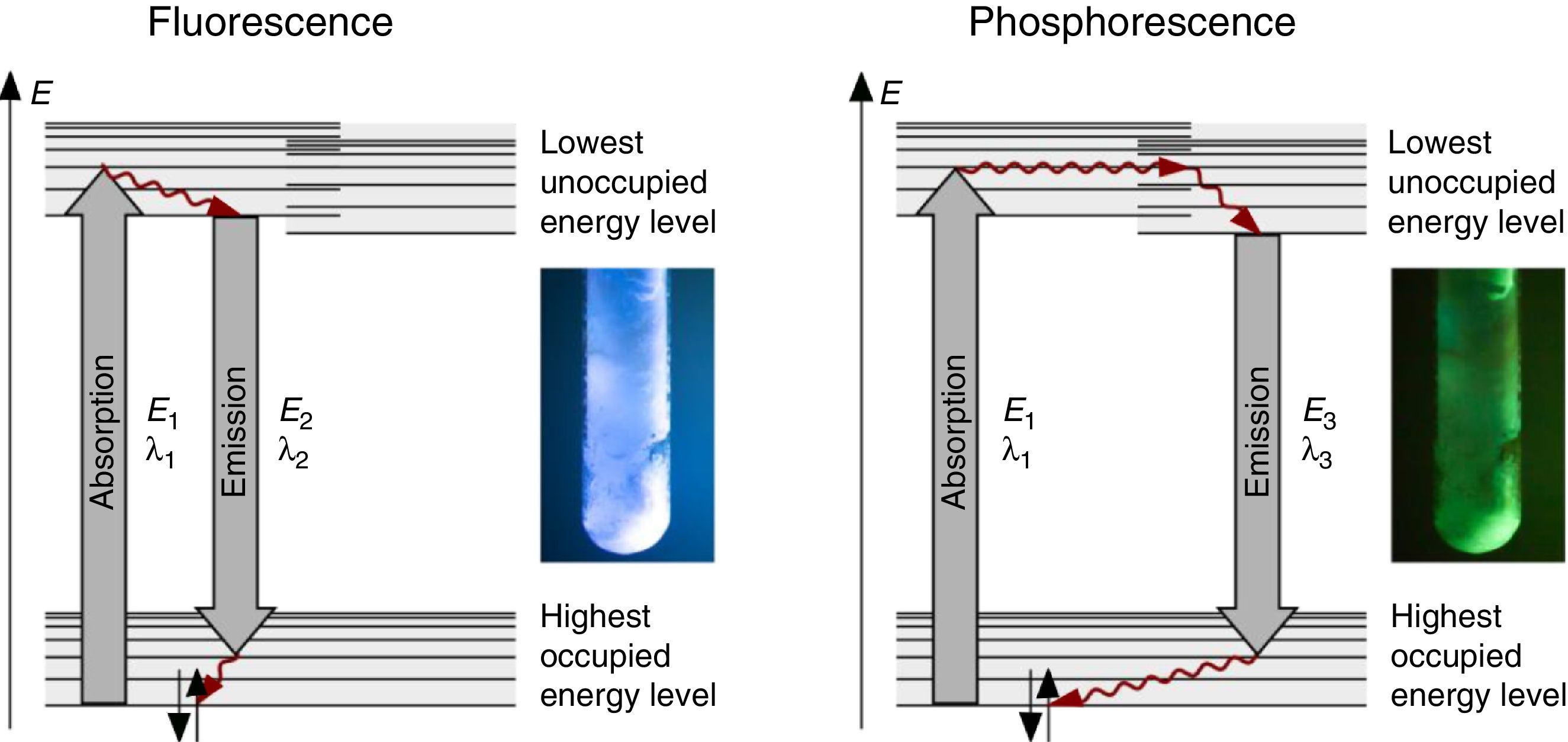

Due to the fact that fluorescence and phosphorescence phenomena nowadays count among everyday experiences of everyone, these should be used for teaching the core concepts of ground state and excited states in molecules.

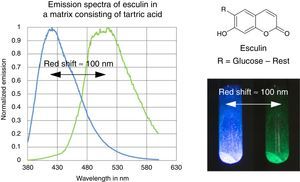

ExperimentsPhosphorescence at room temperatureMelt about 4g of tartric acid in a large test tube over the flame of a Bunsen burner. Heat gently to obtain a clear, molten fluid (it does not need to be colorless). Remove the heat and add about 5mg of esculin to the molten substance. Shake slightly to dissolve the white powder in the tartric acid and then spread the mixture on a large area of the test tube by tilting and rotating it (see video on http://www.chemiedidaktik.uni-wuppertal.de/lehre/photo-mol/en/index.html).

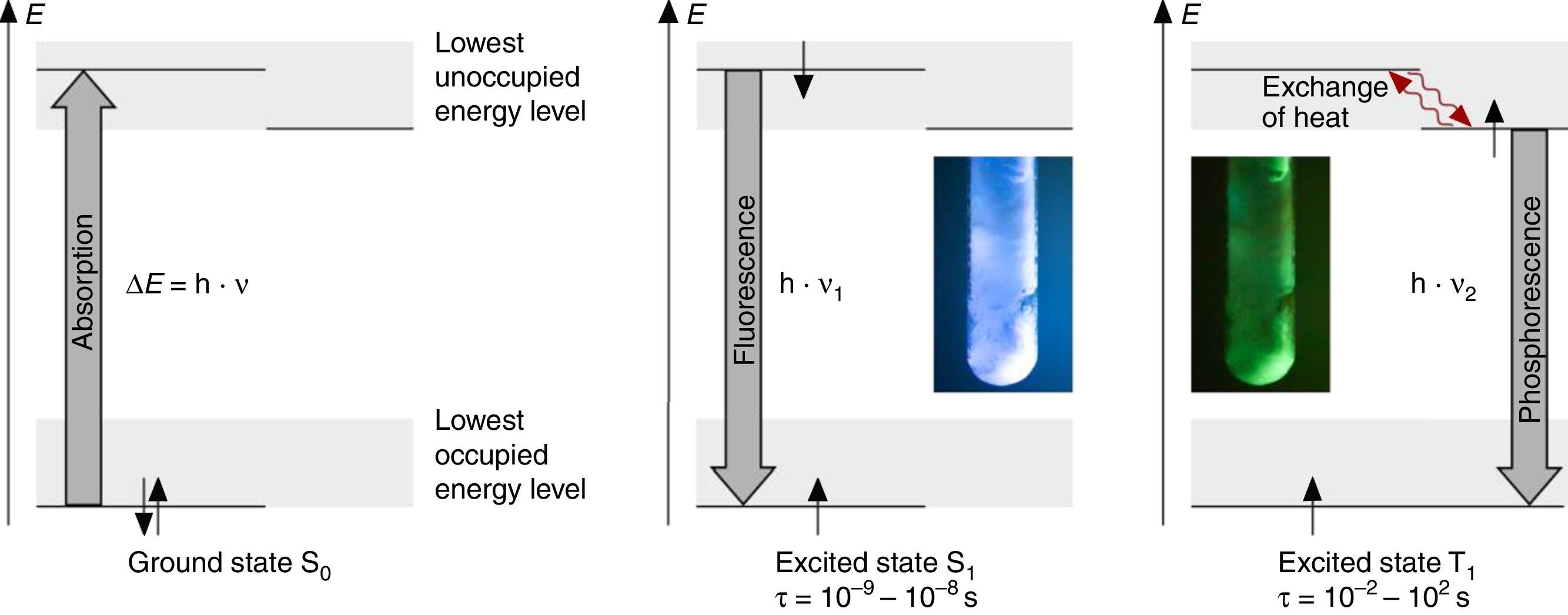

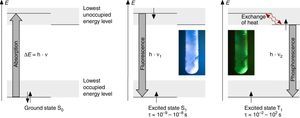

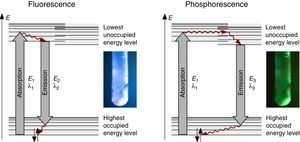

The fluorescence and phosphorescence effects can be explained by the model in Fig. 2, shown using common laboratory UV-light sources (λ=366nm) or even a low cost (approx. 10$) “UV-Flashlight” Ultrafire WF-501B, λ=400nm, FWHM=40nm.

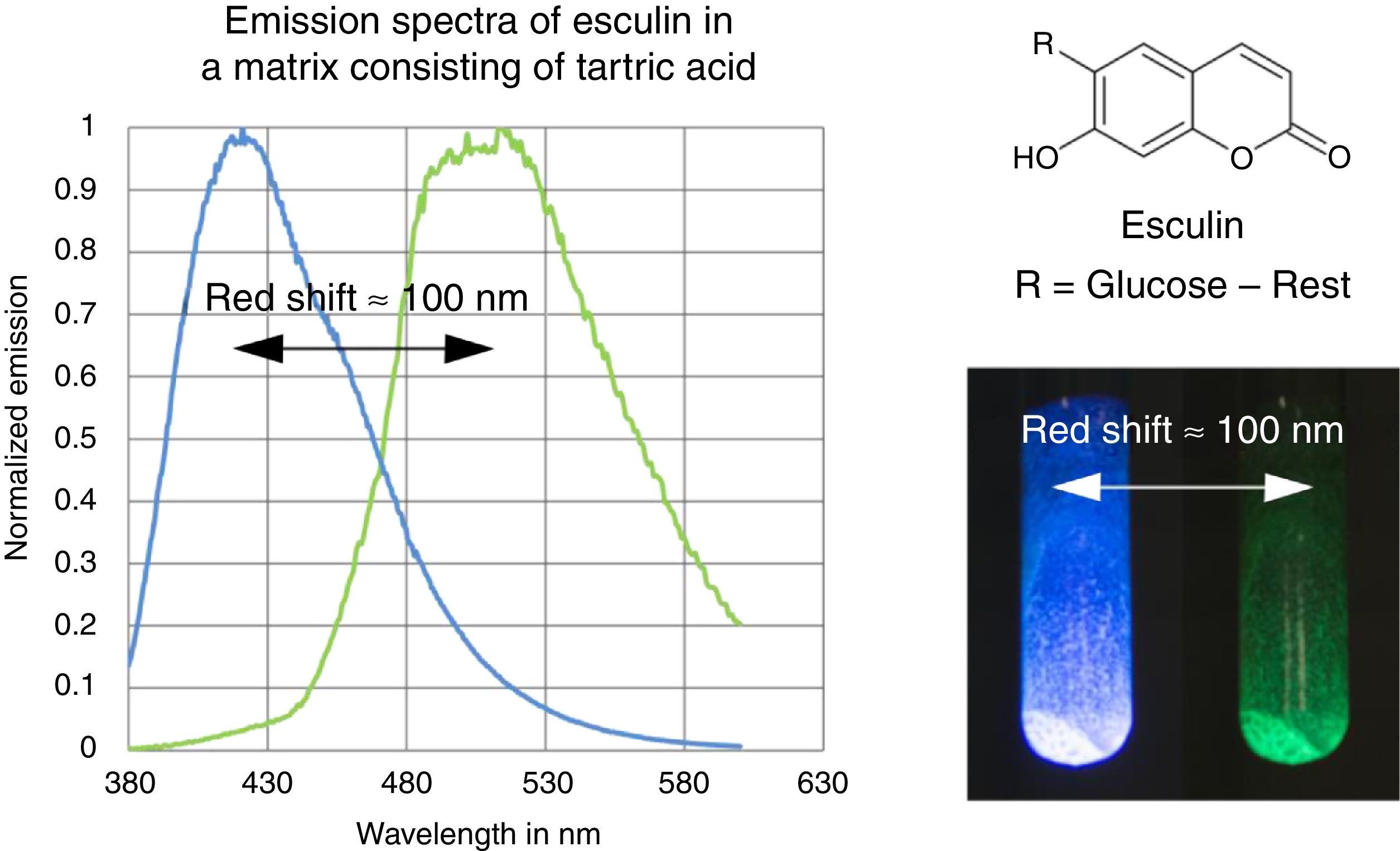

The fluorescence and phosphorescence spectra (Fig. 3) in this article have been recorded using a Varian Cary Eclipse Fluorescence Spectrometer by pouring the molten solution on a glass slide before rigidification.

Temperature dependence of luminescencePrepare three samples according to the instructions above. Heat one of the samples to 60°C using hot water. Cool another sample to 0°C using ice (or below in a freezer). Keep the third sample at room temperature. Irradiate all samples simultaneously and observe the color of the fluorescence and the occurrence and duration of the phosphorescence.

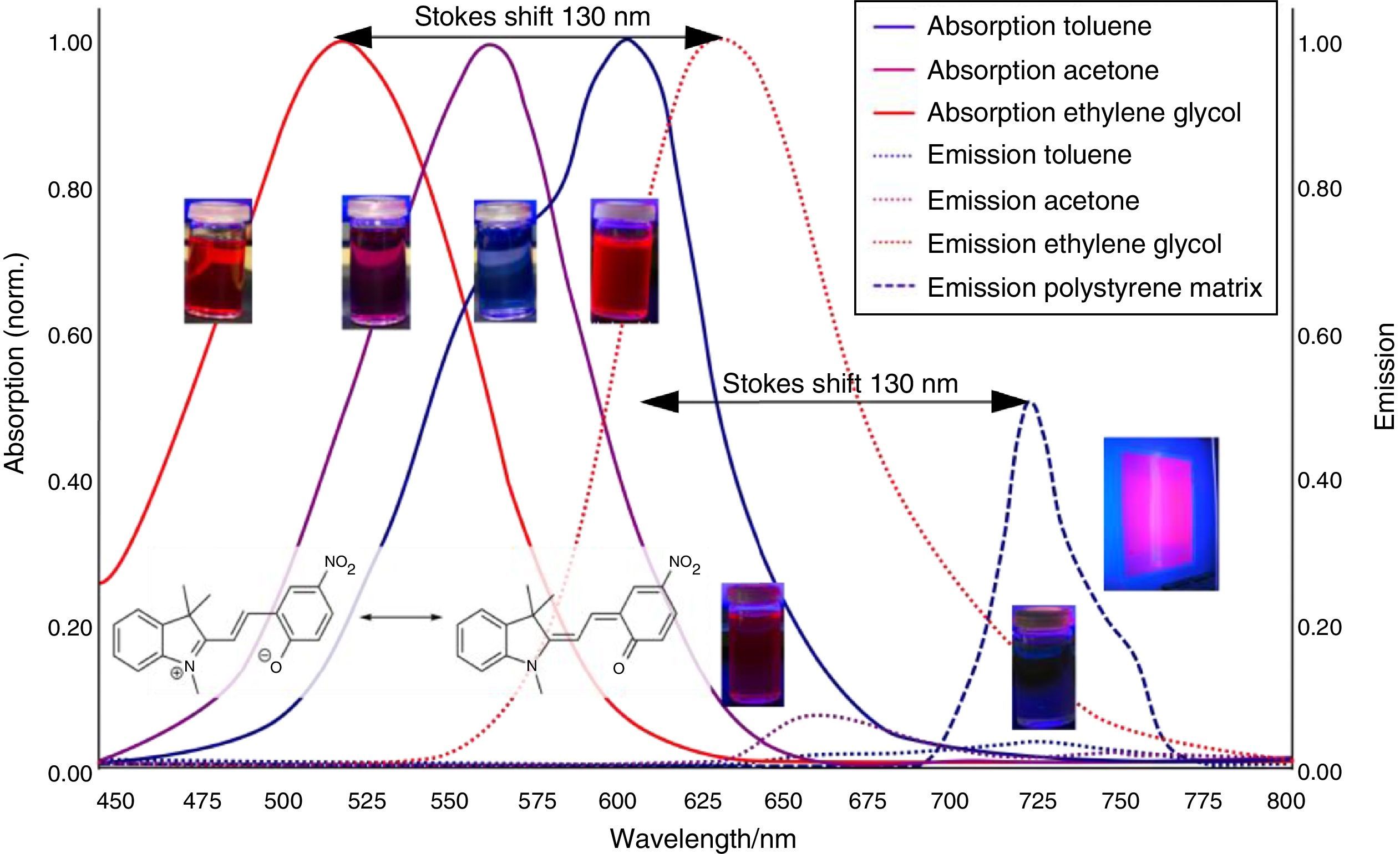

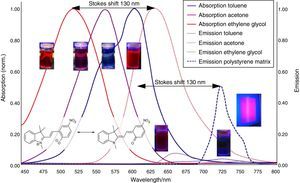

Solvatochromism of spiropyraneDissolve about 10mg spiropyrane in about 10mL toluene, acetone and ethylene glycol respectively. Irradiate the solutions with a common laboratory UV-light source (λ=366nm) or even a low cost “UV-Flashlight” (see above) for 60s. Observe the different colors of the solutions and record spectra using a UV-VIS spectrometer.

The absorption spectra (Fig. 4) in this article have been recorded using a Analytik Jena AG Specord® 200 Plus UV VIS Spectrometer.

Aggregation induced emission of merocyanineDissolve about 10mg spiropyrane in about 10mL toluene and ethylene glycol respectively. Irradiate the solutions in a dark room with a common laboratory UV-light source (λ=366nm) or even a low cost “UV-Flashlight” (see above). The bright red emission in ethylene glycol can be observed with the naked eye, while the toluene solution remains dark.

The corresponding fluorescence spectra (Fig. 4) in this article have been recorded using a Varian Cary Eclipse Fluorescence Spectrometer.

Preparation of a rigid matrix of spiropyrane in polystyreneDissolve about 30mg spiropyrane in 10mL toluene (or xylene). Add about 3–4g polystyrene until a viscous solution is obtained. The polystyrene should be styrofoam (i.e. chunks from packaging). Let the solution settle for a few minutes, so that the enclosed gas can leave the solution. Fix a transparent foil to a level surface using tape. Spread the mixture thinly using a glass rod on the foil. Let the film dry for about 15min in a fume cupboard and laminate it afterwards.

The rigidification induced fluorescence can then be shown using common laboratory UV-light sources (λ=366nm) or even a low cost “UV-Flashlight” (see above).

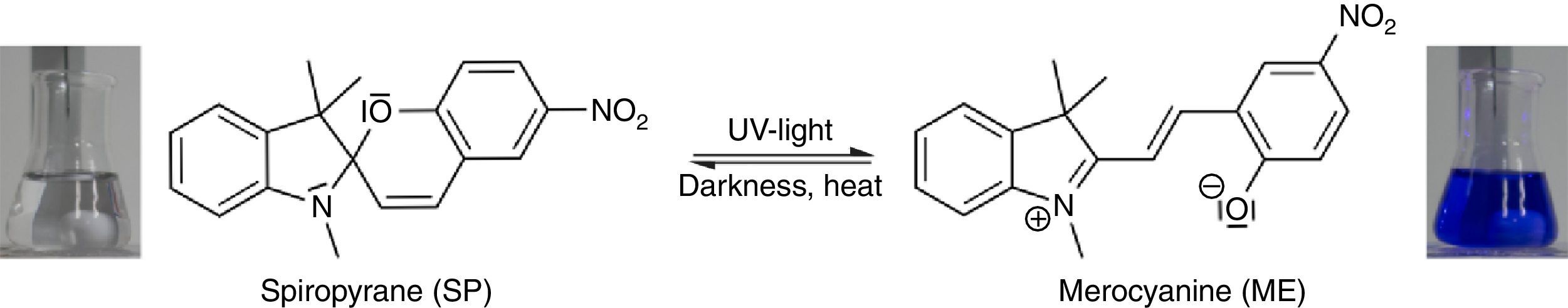

The corresponding isomerization is shown in Fig. 5, and the fluorescence spectrum is shown in Fig. 4. Fluorescence spectra in this article have been recorded using a Varian Cary Eclipse Fluorescence Spectrometer.

Hazards and safetyHeeding the common laboratory safety regulation there are no hazards.

Discussion and teaching recommendationsThe color and the duration of light emission observable in the experiments described above provide convincing phenomena for introducing the concept of the ground state of molecules and the two principal types of excited states, the singlet state S1 and the triplet state T1. In this sense the different colors of fluorescence and phosphorescence shown in Fig. 2 are in full agreement with theoretical predictions.

Similar experiments with fluorophors adsorbed on filter-paper (Schulman, 1976), immobilized in PMMA (Gilbert, 1977) or in boric acid (Roalstad, Rue, LeMaster, & Lasko, 1997) have been reported.

In contrast to some chemicals used in the references above, both tartric acid and esculin are non-hazardous and commercially available at a low price. Furthermore the preparation procedure of the samples as well as their investigation is fast and simple. We provide online on our website (http://www.chemiedidaktik.uni-wuppertal.de/lehre/photo-mol/en/index.html) a video clip showing the preparation of the luminescent sample and different model animations for explaining the Stokes shift of the fluorescence as well as the red shift of the phosphorescence compared to the fluorescence.

For teaching aims, at a first education level a very rough simplification of the Jablonski diagram is proposed in Fig. 2. The main reason for this simplification is the introduction of the concept of the ground state S0 and two types of excited states, the singlet state S1 and the triplet state T1, both of them strongly related to observable and well distinguishable phenomena. In fact Fig. 2 provides theoretical reasons for the phenomenological differences between fluorescence and phosphorescence in our experiment, but it is not able to explain the Stokes shift – the red shift of fluorescence light compared to the exciting radiation. In our experiment however, the luminescent sample is irradiated with UV light at λ=366nm and the maximum of the fluorescence emission occurs at λ=421nm as shown in Fig. 3. To explain this, an improved energy level model, including vibrational states inside of the same electronic states, is needed (Fig. 6). Without going into detail of the quantum mechanics involved (i.e. Born-Oppenheimer approximation and Franck-Condon principle), it can be made understandable that vibrational motions in molecules occur much more slowly (approx. 10−12s) than electron transitions (approx. 10−15s). In general the absorption of the exciting photon by a molecule leads to a higher vibrational level of the excited state S1 as shown in Fig. 6. The following vibrational relaxation (waved arrow in Fig. 6) occurs radiationless with the loss of a small amount of heat. From the lowest vibrational state of S1 the molecule deactivates by emitting a fluorescence photon, leading again to a higher vibrational state of So. From there it again relaxes into the lowest vibrational state of So by loss of heat. Following the complete cycle of elementary processes indicated in Fig. 6, one can understand why the emitted photon hν2 is less energetic than the absorbed photon hν1.

This is the reason for the red shifted blue fluorescence compared to the exciting UV light (Stokes shift). In general fluorescence occurs as described here with a so called down conversion of photons.

Due to the fact that the lowest vibrational level of the excited triplet state T1 is even closer to the ground state, an additional down conversion of photons occurs by phosphorescence (Fig. 6). This is also a general rule and plausible given by the experimental observations and the used models described above.

According to the terminology proposed in literature (Mei et al., 2014), this is an example of rigidification induced phosphorescence. In the rigid matrix numerous intermolecular interactions, especially hydrogen bonds, collectively lock the conformations of the esculin molecules. As a result of this the generation of excited triplet states and the deactivation via phosphorescence is improved.

The luminescence experiments at different temperatures show that the cooler the sample is, the longer the phosphorescence can be observed. The hot sample does not show phosphorescence and the luminescence during irradiation changes from bluish-white to blue. These results confirm the transitions shown in Fig. 2, including the thermal equilibrium between S1 and T1.

In order to demonstrate the phenomenon of aggregation induced luminescence (Ma et al., 2016; Mei et al., 2014) in classroom experiments, we use the hazard-free and commercially available spiropyrane, which is known for more than 60years (Bergmann, Weizmann, & Fischer, 1950). Colorless spiropyrane in toluene (or xylene) solution is converted rapidly into its blue isomer merocyanine (Fig. 5) by irradiation with violet LED light or with sunlight (Tausch, 2005).

The reverse reaction of merocyanine to spiropyrane, observable by the decoloration of the solution, occurs spontaneously in darkness. It can be accelerated by heating or by irradiation with green light (Tausch, 2005; Tausch & Wachtendonk, 2007, http://www.chemiedidaktik.uni-wuppertal.de/lehre/photo-mol/en/index.html).

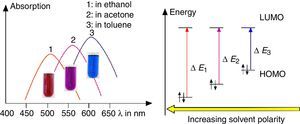

The results of the experiments regarding Aggregation Induced Emission (AIE) are summarized in Fig. 4.

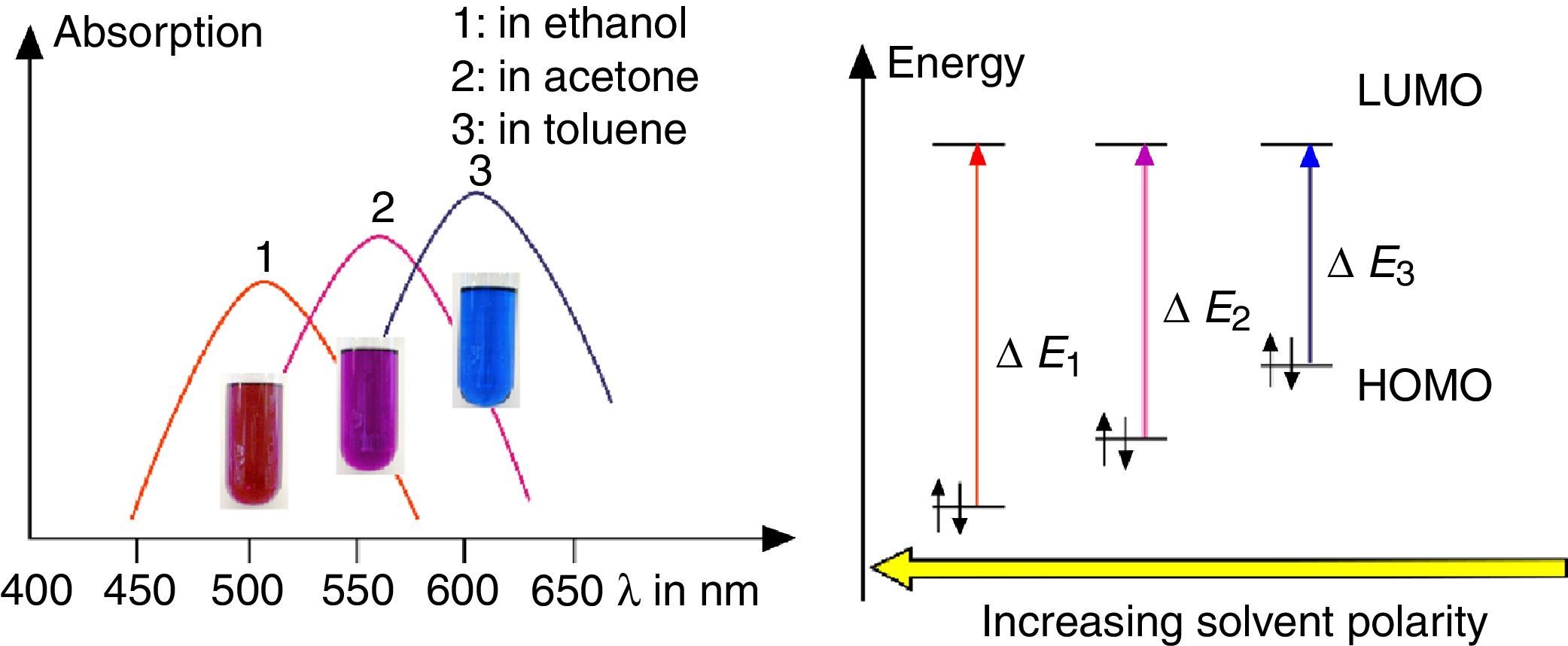

As shown in Fig. 7, the color of merocyanine in toluene, acetone and ethylene glycol solution changes from blue over violet to red. Accordingly, the absorption maxima shift toward shorter wavelengths (negative solvatochromism; continuous lines in Fig. 4).

This is a characteristic behavior of dye molecules with a bipolar or even a zwitterionic resonance structure. Actually, merocyanine is an appropriate compound for explaining the phenomenon of negative solvatochromism. Again the energy level model is used, this time in an oversimplified version without vibrational levels (Fig. 7). The hypothesis is that, due to the electrostatic interaction of merocyanine zwitterions with the polar molecules of the solvent, the highest occupied energy level (HOMO) becomes lowered, whereas the lowest unoccupied energy level (LUMO) remains unmodified. Consequently, the energy ΔE of the photons able to excite the merocyanine molecules in a more polar solvent has to be higher than in a less polar one. This effect should be increasingly distinct, the more polar the solvent molecules are. Following this line of thought, one gets a pretty good idea for the behavior of merocyanine concerning light absorption in solvents of different polarities (Fig. 4, 7).

In the case of merocyanine the ability to emit light also depends strongly on the molecular environment. In our experiments, it is easily observable that a solution of merocyanine in the non-polar solvent toluene does not emit light, whereas a solution in the polar solvent ethylene glycol (as well as in a solid matrix of non-polar polystyrene) shows a bright red fluorescence.

The fluorescence of merocyanine in the polar solvent ethylene glycol and in the non-polar rigid matrix of polystyrene can and should be explained using the concepts of aggregation induced luminescence (Ma et al., 2016; Mei et al., 2014) and rigidification induced luminescence respectively (Yuan et al., 2010). In this sense one assumes that merocyanine zwitterion molecules aggregate in cages of polar solvent molecules. This aggregation leads to the restriction of intramolecular motions in merocyanine molecules. Thus the deactivation route of excited merocyanine molecules via vibronic relaxation is hindered or even suppressed and the deactivation by emission of photons is enhanced. In contrast to the ethylene glycol solution there is no aggregation of merocyanine molecules in the non-polar solvent toluene and intramolecular motions are not restricted. The deactivation of excited merocyanine molecules occurs mostly radiationless via vibronic relaxation. Immobilized in a rigid matrix, even in a non-polar one, the flexibility of merocyanine molecules becomes considerably limited and consequently the deactivation via fluorescence gets enhanced. Note that in both cases, in the polar ethylene glycol as well as in the non-polar polystyrene, according to the theoretical prediction (Fig. 6) the emitted photons are down converted compared to the absorbed photons. Actually, the absorption and emission spectra in Fig. 4 indicate a Stokes shift of approximately 130nm.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

We acknowledge the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG) for supporting the project “Photoprocesses in Science Education” (“Photoprozesse in der Lehre der Naturwissenschaften” Photo-LeNa, TA 228/4-1).

Peer Review under the responsibility of Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.