Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic inflammatory autoimmune disease. Despite the influence of diet on inflammation, dietary habits in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) are not well established. The study objective was to assess dietary intake and nutritional status in SLE patients.

Patients and methodsA cross-sectional study was conducted in 92 patients with SLE. Nutritional status was determined by body mass index (BMI) and energy/nutrient distribution of diet was analyzed and compared to a control group. Dietary reference intakes (DRIs) issued by the Spanish Societies of Nutrition, Feeding and Dietetics (FESNAD) and the Spanish Society of Community Nutrition (SENC) were used as reference.

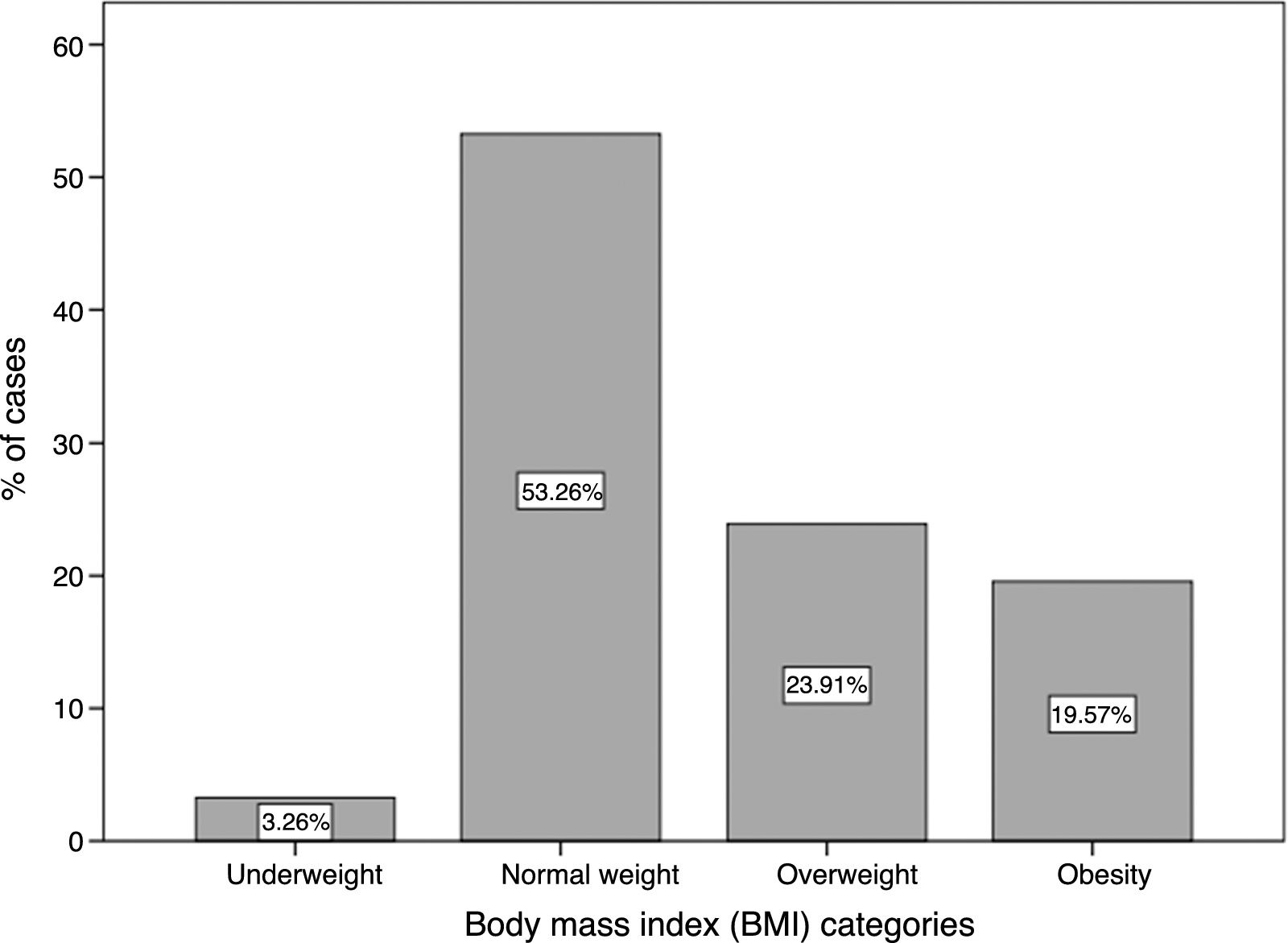

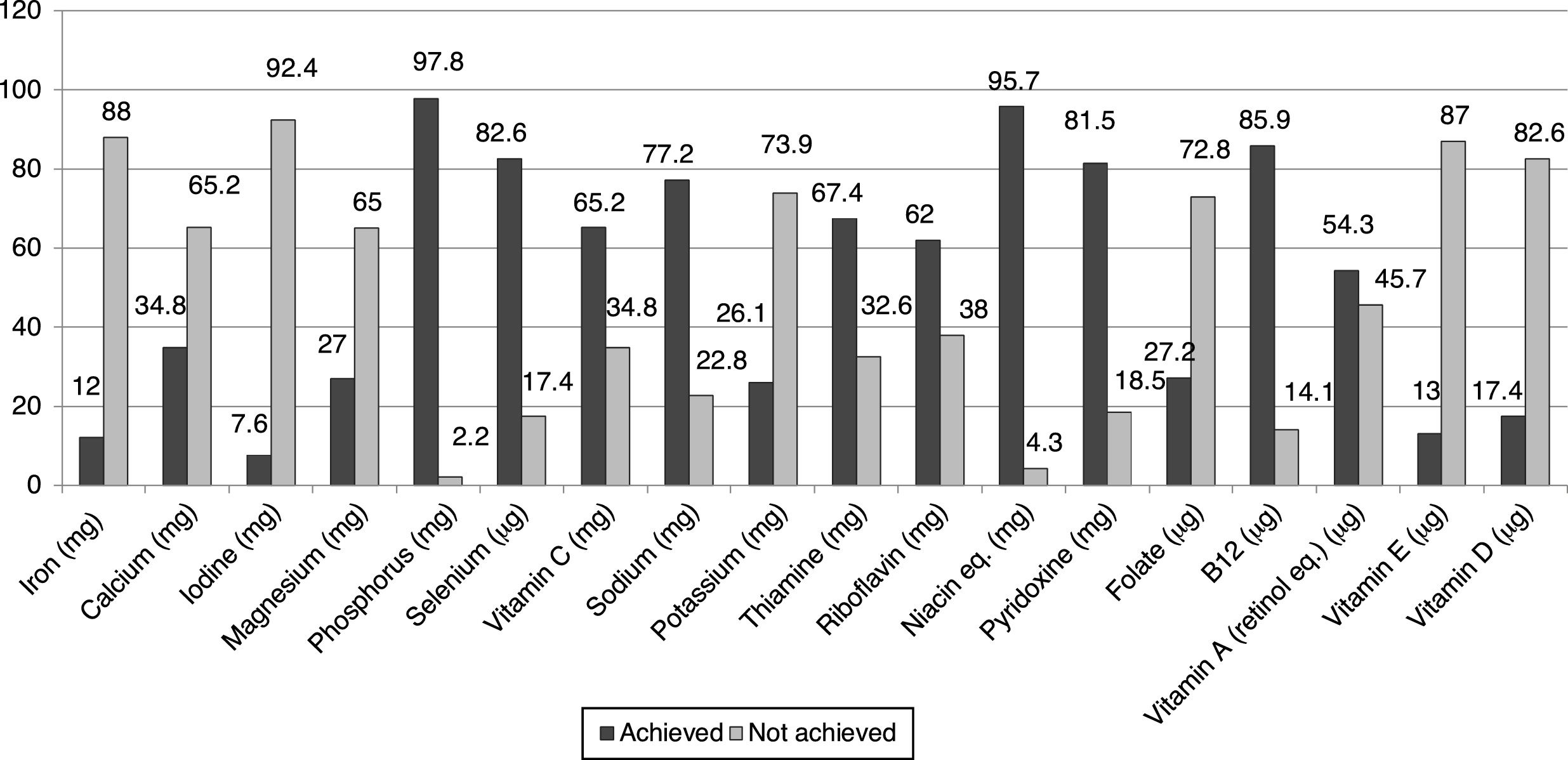

ResultsBody mass index was normal in 53.26% of patients, while 43.48% had excess weight. Energy, protein, and fat intake was significantly lower in the SLE group (p=0.003, p=0.000, and p=0.001 respectively). Protein and fat contribution to total energy was higher, while that of carbohydrate and fiber was lower than recommended. Most patients did not reach the recommended intake for iron (88%), calcium (65.2%), iodine (92.4%), potassium (73.9%), magnesium (65%), folate (72.8%), and vitamins E (87%) and D (82.6%), but exceeded the recommendations for sodium and phosphorus.

ConclusionsSpanish SLE patients have an unbalanced diet characterized by low carbohydrate/fiber and high protein/fat intakes. Significant deficiencies were seen in micronutrient intake. Dietary counseling to improve nutrition would therefore be advisable in management of SLE.

El lupus eritematoso sistémico (LES) es una enfermedad autoinmune, crónica e inflamatoria. La dieta tiene un importante impacto en este tipo de enfermedades. Así, el objetivo de este estudio fue conocer la ingesta dietética y el estado nutricional en pacientes con LES.

Pacientes y métodosSe realizó un estudio transversal que incluyó 92 pacientes diagnosticados de LES. Se determinó el estado nutricional y la ingesta dietética de los pacientes contrastando con un grupo control usando como referencia las recomendaciones de la Federación Española de Sociedades de Nutrición, Alimentación y Dietética (FESNAD) y la Sociedad Española de Nutrición Comunitaria (SENC).

ResultadosEl índice de masa corporal (IMC) fue normal en el 53,26% de los pacientes, mientras que el 43,48% se ubicó en categorías de exceso. La ingesta calórica, proteica y de grasas fue significativamente menor en el grupo con LES (p=0,003, p=0,000 y p=0,001, respectivamente). La contribución de la ingesta proteica y de grasa a la energía total fue mayor que la recomendada, mientras que la de carbohidratos y fibra, menor. La mayoría de los pacientes no alcanzaron las recomendaciones de ingesta de hierro (88%), calcio (65,2%), iodo (92,4%), potasio (73,9%), magnesio (65%), folato (72,8%), vitaminas E (87%) y D (82,6%) y excedieron las de sodio y fósforo.

ConclusionesLa dieta de los pacientes con LES analizados no es equilibrada en el consumo de macronutrientes y fibra, observándose deficiencias en la ingesta de micronutrientes esenciales. Por lo tanto, sería aconsejable el asesoramiento dietético como parte de su tratamiento.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic disease characterized by an abnormal inflammatory and autoimmune response due to the presence of hyperactive B cells and the production of autoantibodies that, in conjunction with the impaired removal of apoptotic cellular material, results in the formation of immune complexes. These complexes induce inflammatory reactions, causing the tissue inflammation and damage associated with SLE.1

Recently, nutrition and lifestyle patterns have emerged as important factors influencing the health of individuals, including the inflammatory response. Several pieces of evidence support the fact that nutritional status influences the development and prognosis of inflammatory diseases. In this context, a diet rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids, fiber, vegetables, and fruit, combined with physical activity, has been shown to improve the quality of life of patients with rheumatoid arthritis2–4 or cancer,5,6 as well as prevent the incidence, and even slow the progression of the disease through the modulation of several inflammatory pathways.7,8

In SLE, evidence from studies of patients and animal models suggests that a balanced diet including a moderate calorie and protein content but high in vitamins, minerals (especially antioxidants), and mono/polyunsaturated fatty acids, can protect against tissue damage and suppress inflammatory activity.9 In addition, this dietary pattern prevents overweight, insulin resistance, and thus decreases the risk of developing cardiovascular disease, one of the most common complications in SLE patients.10

The nutritional status and food intake of patients with SLE may therefore influence the course of the disease. However, in most countries there is very limited knowledge on the patterns and nutritional adequacy of the diet of lupus sufferers compared to normal or healthy people. In particular, to our knowledge, this issue has not previously been addressed in Spanish SLE patients.

Considering all this evidence, the aim of this study was to assess the dietary intake and nutritional status of Spanish patients with SLE in order to determine whether they achieve a well-balanced diet and nutrient intake and estimate possible nutritional differences between this group and the general population.

Subjects and methodsStudy groupA cross-sectional study was designed, and 92 patients diagnosed with SLE were recruited in the Outpatient Clinic of the Systemic Autoimmune Diseases Unit at San Cecilio University Hospital in Granada (Spain). All the SLE patients included met the diagnostic criteria according to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) revised classification or SLICC criteria11–13 and had been diagnosed with the disease at least one year prior to the study. Disease activity was determined using the SLEDAI-2K.14 Patients with late-stage lupus, serum creatinine ≥1.5mg/dl, diabetes mellitus, ischemic heart diseases, cerebrovascular disease, recent infections, trauma or surgery, SLICC >5, pregnancy and/or other chronic and/or autoimmune systemic conditions not related with the main disease were excluded from the study. All participants received verbal and written information on the nature and purpose of the study and gave their written consent for their participation. Ethical approval for the work was obtained from the local Ethics Committee (CEI Granada) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Nutritional assessmentDietary intake was assessed through a 24-h diet recall in a personal interview carried out by a trained nutritionist-dietician in which the participants were asked, meal by meal, about portions and amounts of each food consumed, the number and amount of ingredients used in each recipe, as well as questions relating to menu preparation (type of oil, milk, or cheese used) as well as sweets, alcoholic and non-alcoholic drinks, and added sugar. To improve the accuracy of the food quantities recorded, standard household measures and pictorial food models were used.

Food records were converted to nutrient intake using a computerized nutrient analysis program (Nutriber 1.1.5). Energy contribution was calculated in terms of percentage (%) of each macronutrient considering that one gram of protein or carbohydrates equals 4 kilocalories and each gram of fat equals 9 kilocalories.

Nutritional status was determined by body mass index (BMI). Patients were classified as malnourished (BMI¿18.5kg/m2), normal weight (BMI 18.6–24.9kg/m2), overweight (BMI 25–29.9kg/m2), or obese (BMI≥30kg/m2), based on World Health Organization criteria.15

Energy and nutrient intake of lupus patients was compared to nutritional data as reference obtained from the Spanish National Dietary Intake Survey (ENIDE) carried out in 2011.16 ENIDE is a representative national-level study of food and nutrient intake in the adult population. It was based on a random selection of more than 3323 individuals, providing a 95% confidence level and an accuracy of 1.8%.16 As our study population included 92.4% women with a mean age of 44.3, data from the female population aged 18–64 years was selected as a reference to compare with the cohort of lupus sufferers.

Dietary reference intakes (DRI) for the Spanish population issued by the Spanish Societies of Nutrition Feeding and Dietetics (FESNAD),17 in 2010, and the Spanish Society of Community Nutrition (SENC)18 dietary guidelines and nutrition goals for the Spanish population19 were taken as references to interpret the 24-h food and beverage recall.

Statistical analysisThe information obtained was recorded and analyzed using the statistics program SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Science) for Windows, version 22. We described numeric variables through the median±standard deviation while qualitative or nominal variables were described through percentages and frequencies. Differences in the mean dietary intake of energy and nutrients between SLE patients and the control population were estimated with Student's or Welch's t-test. The values were considered significant when p was <0.05.

ResultsNinety-two percent (92.3%) of the patients were female and 7.7% were male. The mean age of the study cohort was 44.47±13.45 and the mean time since being diagnosed with SLE was 7.85±4.29 years. All study participants showed a low to moderate activity of the disease (mean SLEDAI: 3.52) and very low damage index (mean SLICC: 1.27), ranging from 0 to 5.

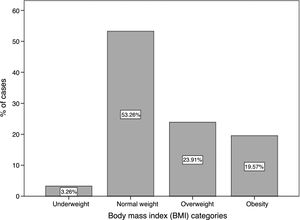

Nutritional status according to BMI is shown in Fig. 1. Of note, 53.26% of patients were in the normal range for BMI and 43.48% were in either the overweight or obesity categories; only 3.26% of the lupus population was underweight.

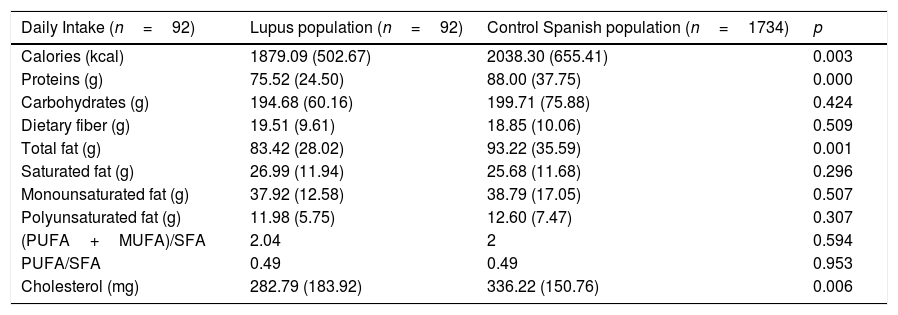

The percentage of calories, protein, total fat intake, and dietary cholesterol intake was significantly lower in lupus patients than the Spanish population data used as a control (p=0.003, p=0.000, p=0.001 and p=0.006, respectively). No significant differences were observed for other nutrients such as total carbohydrates, fiber, and fatty acid intake (Table 1).

Mean dietary intake of energy and nutrients in SLE patients compared with Spanish population as control.

| Daily Intake (n=92) | Lupus population (n=92) | Control Spanish population (n=1734) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calories (kcal) | 1879.09 (502.67) | 2038.30 (655.41) | 0.003 |

| Proteins (g) | 75.52 (24.50) | 88.00 (37.75) | 0.000 |

| Carbohydrates (g) | 194.68 (60.16) | 199.71 (75.88) | 0.424 |

| Dietary fiber (g) | 19.51 (9.61) | 18.85 (10.06) | 0.509 |

| Total fat (g) | 83.42 (28.02) | 93.22 (35.59) | 0.001 |

| Saturated fat (g) | 26.99 (11.94) | 25.68 (11.68) | 0.296 |

| Monounsaturated fat (g) | 37.92 (12.58) | 38.79 (17.05) | 0.507 |

| Polyunsaturated fat (g) | 11.98 (5.75) | 12.60 (7.47) | 0.307 |

| (PUFA+MUFA)/SFA | 2.04 | 2 | 0.594 |

| PUFA/SFA | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.953 |

| Cholesterol (mg) | 282.79 (183.92) | 336.22 (150.76) | 0.006 |

Notes: Values are means±SD (standard deviation).

PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acids; MUFA, monounsaturated fatty acids; SFA, saturated fatty acids.

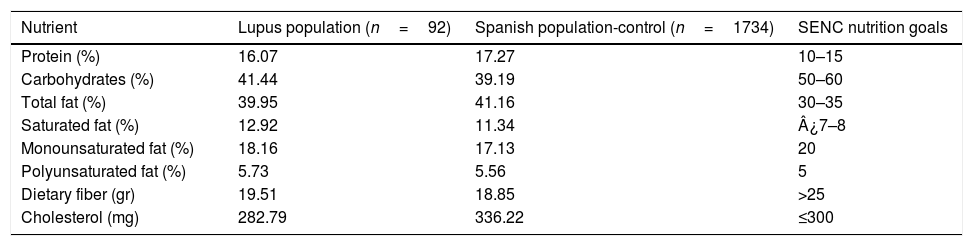

With regard to the energy contribution of macronutrients, similarly to the control group, protein represented 16.07% of the total energy intake for SLE patients (Table 2). Thus, protein contribution was excessive in both lupus sufferers and the general Spanish population when compared to SENC recommendations.18 Conversely, both lupus patients and the control subjects showed a pattern of low carbohydrate levels in their diets, with figures below the SENC recommendations (50–60%) (Table 2). Total fat intake was notably higher in both lupus patients (39.95%) and the control population (41.16%) compared to the SENC recommendations, which suggest a range of 30–35%. Nevertheless, monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acid goals were reached in both lupus sufferers and the control population. In addition, lupus patients and the control population consumed low amounts of dietary fiber according to SENC goals (Table 2).

Energy contribution of macronutrients, fiber and fat sources in lupus population and Spanish control population (ENIDE study) compared to Spanish Society of Community Nutrition (SENC) nutrition goals.

| Nutrient | Lupus population (n=92) | Spanish population-control (n=1734) | SENC nutrition goals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein (%) | 16.07 | 17.27 | 10–15 |

| Carbohydrates (%) | 41.44 | 39.19 | 50–60 |

| Total fat (%) | 39.95 | 41.16 | 30–35 |

| Saturated fat (%) | 12.92 | 11.34 | ¿7–8 |

| Monounsaturated fat (%) | 18.16 | 17.13 | 20 |

| Polyunsaturated fat (%) | 5.73 | 5.56 | 5 |

| Dietary fiber (gr) | 19.51 | 18.85 | >25 |

| Cholesterol (mg) | 282.79 | 336.22 | ≤300 |

Notes: Values are expressed in percentage (%) according to dietary contribution of each nutrient.

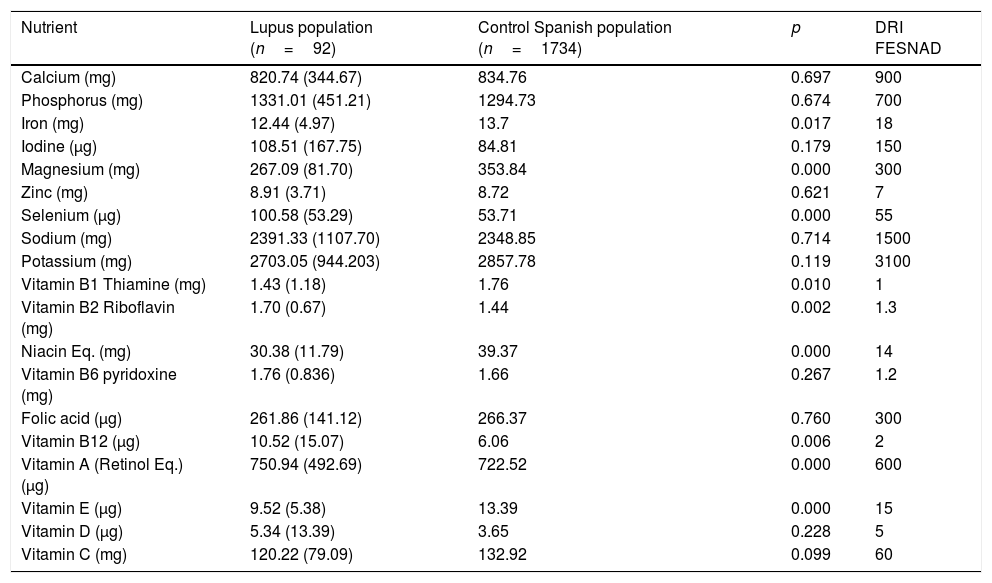

Interestingly, significant differences were seen in the vitamin and mineral intake of lupus patients compared with the Spanish population used as a control (Table 3). In lupus patients, a significantly lower intake was reported for magnesium, iron, thiamine, niacin, and vitamin E (p=0.000, p=0.017, p=0.010, p=0.000, respectively); while there was an inverse relationship for selenium, riboflavin, vitamin B12, and vitamin A (p=0.000, p=0.002, p=0.006, p=0.000, respectively) (Table 3). Both groups met the FESNAD suggested daily intake levels for thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, vitamin B12, and vitamin A, but did not achieve the recommended levels for calcium, iron, iodine, potassium, folic acid, or vitamin E. For both groups, the sodium and phosphorus intakes exceeded daily recommendations. An interesting finding was that dietary magnesium was below the FESNAD recommendations only in SLE patients.

Mean micronutrient intake in SLE patients compared with Spanish dietary reference intake (DRI).

| Nutrient | Lupus population (n=92) | Control Spanish population (n=1734) | p | DRI FESNAD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium (mg) | 820.74 (344.67) | 834.76 | 0.697 | 900 |

| Phosphorus (mg) | 1331.01 (451.21) | 1294.73 | 0.674 | 700 |

| Iron (mg) | 12.44 (4.97) | 13.7 | 0.017 | 18 |

| Iodine (μg) | 108.51 (167.75) | 84.81 | 0.179 | 150 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 267.09 (81.70) | 353.84 | 0.000 | 300 |

| Zinc (mg) | 8.91 (3.71) | 8.72 | 0.621 | 7 |

| Selenium (μg) | 100.58 (53.29) | 53.71 | 0.000 | 55 |

| Sodium (mg) | 2391.33 (1107.70) | 2348.85 | 0.714 | 1500 |

| Potassium (mg) | 2703.05 (944.203) | 2857.78 | 0.119 | 3100 |

| Vitamin B1 Thiamine (mg) | 1.43 (1.18) | 1.76 | 0.010 | 1 |

| Vitamin B2 Riboflavin (mg) | 1.70 (0.67) | 1.44 | 0.002 | 1.3 |

| Niacin Eq. (mg) | 30.38 (11.79) | 39.37 | 0.000 | 14 |

| Vitamin B6 pyridoxine (mg) | 1.76 (0.836) | 1.66 | 0.267 | 1.2 |

| Folic acid (μg) | 261.86 (141.12) | 266.37 | 0.760 | 300 |

| Vitamin B12 (μg) | 10.52 (15.07) | 6.06 | 0.006 | 2 |

| Vitamin A (Retinol Eq.) (μg) | 750.94 (492.69) | 722.52 | 0.000 | 600 |

| Vitamin E (μg) | 9.52 (5.38) | 13.39 | 0.000 | 15 |

| Vitamin D (μg) | 5.34 (13.39) | 3.65 | 0.228 | 5 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 120.22 (79.09) | 132.92 | 0.099 | 60 |

Values are expressed as means±SD (standard deviation).

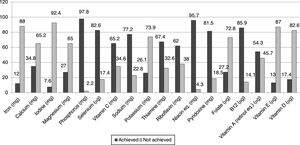

The vast majority of lupus patients showed a very low compliance with micronutrient intake recommendations, with iron (88%), calcium (65.2%), iodine (92.4%), potassium (73.9%), magnesium (65%), folate (72.8%), vitamin E (87%), and vitamin D (82.6%) intakes being below daily dietary recommendations, whereas sodium and phosphorus exceeded the daily suggested intakes, just as in the Spanish control population (Fig. 2).

DiscussionIn this study, for the first time, we evaluated nutritional status and analyzed dietary intake in a well-characterized, medically stable cohort of lupus patients. The study group included a very low prevalence of undernutrition according to BMI and the WHO classification. This is probably because the participants were ambulatory and had controlled disease with no late-stage complications, appetite suppression, or weight loss. In fact, previous studies conducted on different populations of lupus patients have shown similar results, with underweight values being around 1–2%, overweight between 35.3% and 35.9%, and obesity at 27.7%–28.3%.20,21

With regard to the dietary habits of lupus sufferers, we found that they consumed significantly less amounts of energy, protein, total fat, and cholesterol compared with average intakes in the control Spanish population (ENIDE). Additionally, our data supports the finding that the diet of lupus patients and the Spanish population in general, is characterized by an imbalance in macronutrient energy contribution with a low carbohydrate, high protein/fat diet pattern together with more saturated fat and less fiber intake than SENC recommendations. To our knowledge, only two previous studies have assessed this issue in lupus patients.10,20

Elkan et al. (2012), evaluated macronutrient intake in Swedish SLE patients and reported a decreased intake of polyunsaturated fatty acids (omega-3 and omega-6) and fiber, and an increased intake of carbohydrates, compared with a control population. In another study assessing dietary habits in a Brazilian lupus cohort, a high consumption of fats and oils was reported.20 Thus, our data, when taken together with previous findings, points to the fact that there is a similar trend in lupus sufferers to that seen in the general population; SLE patients’ dietary habits are marked by a high fat – low fiber intake. Therefore, in the context of an autoimmune inflammatory disease such as SLE, it is important to consider that both fat and fiber intake can either directly or indirectly modify immune and inflammatory responses. Saturated fatty acid (SFA) intake correlates with a pro-inflammatory response upregulating several genes of inflammatory pathways, while monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) exhibit an anti-inflammatory profile. Fiber intake has been inversely associated with plasma homocysteine and inflammatory markers including IL-6 and CRP (C-reactive protein).22–24 Considering this, dietary interventions to increase fiber intake to 25 grams/day, as suggested by SENC,18 PUFAs, MUFAs and decrease saturated fat consumption, should be considered to help reduce both inflammation and cardiovascular risk in lupus patients, as well as in the Spanish population.22,25–27

Another important aspect is that lupus patients presented several micronutrient deficiencies. Specifically, there were significantly low intakes of iron, magnesium, folic acid, vitamin B1, niacin and vitamin E. Our findings are in line with the study of Borges et al., conducted on a Brazilian cohort of lupus sufferers, which showed an inadequate intake of iron and vitamin B12. Interestingly, some of these micronutrients have been shown to influence the immune response.21

Magnesium deficiency seems to contribute to an exaggerated immune stress response, proatherogenic changes in lipoprotein metabolism, endothelial dysfunction, thrombosis, and hypertension, which explains the aggravating effect of magnesium deficiency on the course of inflammatory diseases.28 In addition, lower levels of serum magnesium in SLE patients compared to controls have been reported.

Another micronutrient intake level below the RDI in both lupus and the Spanish population was folic acid. Elevated homocysteine levels are common in chronic immune-mediated disorders and lead to accelerated atherosclerosis and increased cardiovascular risk.29 Folic acid is critical in determining plasma homocysteine levels.30 A very recent study showed that folate was associated with several markers of atherosclerosis and vascular disease31; however, previous studies suggest it improves cardiovascular health.32

It has also been suggested that vitamin E can regulate antibody production and suppress autoantibody production in SLE independently of its antioxidant activity.33

Thus, although further studies are required to fully elucidate the impact of these micronutrients in autoimmunity, and specifically in SLE, it might be important to implement nutritional counseling and/or supplement strategies to achieve adequate intakes levels.

We are aware that the cross-sectional design of the study limits our ability to determine causal relationships with the associations detected because it only provides the nutritional status at a specific point in time. In addition, another possible limitation of this study is the fact that the lupus patient's dietary intake was assessed using a 24-hour recall whereas the dietary intake of the ENIDE control population was estimated using both a 24-hour recall and a daily food registry over three random days. To minimize the possibility of bias in the dietary intake of our study population, the 24-hour diet recall data collection was performed in a personal interview conducted by a trained nutritionist-dietician.

In summary, our data supports the fact that diet pattern in SLE patients is characterized by low carbohydrate/fiber levels and a high protein/fat intake similar to the Spanish population. In addition, a poor micronutrient dietary intake was found for calcium, iron, iodine, magnesium, potassium, folic acid, and vitamin E in SLE patients. Considering the high risk of malnutrition, infections, osteoporosis, and cardiovascular diseases in SLE, dietary counseling to help improve nutritional habits in lupus patients should be considered an important strategy in the management of the disease.

Author's contributionThe authors have contributed equally to this work.

Pocovi-Gerardino G performed patient's nutritional assessments, analyzed and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. Correa-Rodríguez M analyzed the data and performed statistical analyses. Callejas-Rubio J-L and Rios-Fernandez R performed patient recruitment and clinical assessment. Ortego-Centeno N contributed to the conception and study design, patient recruitment and reviewed/edited manuscript, Rueda-Medina B contributed to the conception, study design, data interpretation and reviewed/edited manuscript.

Transparency declarationThe corresponding author on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

Acknowledgements & fundingsThis study was supported by the grant PI0523-2016 from “Consejería de igualdad, salud y políticas sociales” (Junta de Andalucía). Pocovi-Gerardino G is a predoctoral fellow from the doctoral program “Medicina clínica y salud pública” of the University of Granada.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.