The aim of this systematic literature review (SLR) was to provide an overview of the Spanish research landscape of observational studies conducted with antidiabetic drugs in T2DM patients, published in the last five years, with special focus on the objectives, methodology and main research areas.

Twenty-two articles, corresponding to 20 studies, were included in the analysis. Around 82% of the studies employed a longitudinal study design, collected data retrospectively (72.7%), and were based on secondary data use (63.6%). Pharmacotherapeutical groups most frequently studied were insulin (31.8%) and DPP4i (13.6%). Analytic design was employed most in the studies (68.2%), followed by descriptive analysis (22.7%). In the top five of the most studied variables are those related to effectiveness assessed according to glycaemic control (91%), treatment patterns (82%), safety (hypoglycaemia) (59%), the identification of effectiveness predictive factors (45%) and effectiveness according to other control measures such as anthropometric control or cardiovascular risk factors (36%).

El objetivo de esta revisión sistemática de la literatura (SLR) fue proporcionar una visión general de los estudios observacionales realizados en España con fármacos antidiabéticos en pacientes con DM2, publicados en los últimos cinco años, con especial atención a los objetivos, metodología y principales áreas de investigación.

Veintidós artículos, correspondientes a 20 estudios, se incluyeron en el análisis. Alrededor del 82% de los estudios tenían un diseño longitudinal, recogieron datos retrospectivamente (72.7%) y se basaron en datos secundarios (63.6%). Los grupos farmacoterapéuticos más frecuentemente estudiados fueron las insulinas (31.8%) y los DPP4i (13.6%). Los diseños analíticos fueron los más utilizados (68,2%), seguidos de los análisis descriptivos (22,7%). Entre las variables más estudiadas se encontraron las relacionadas con efectividad según control glucémico (91%), patrones de tratamiento (82%), seguridad (hipoglucemias) (59%), identificación de factores predictores de efectividad (45%) y efectividad según otras medidas, como control antropométrico o factores de riesgo cardiovascular (36%).

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a major global health problem that causes high human, social and economic cost on countries at all income levels.1 The chronic hyperglycemia of diabetes is associated with long-term damage, dysfunction and failure of various organs, especially of the eyes, kidneys, nerves, heart and blood vessels.2 The progression of diabetes, and especially poor glycaemic control, leads to numerous potentially life-threatening complications as well as a poorer quality of life (QoL).3

According to the 8th edition of the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) Diabetes Atlas, a global reference report setting the standard estimates for DM prevalence and its related burden, this chronic metabolic disorder affected 451 million adults globally in 2017, and this number is further estimated to rise to 693 million by 2045. Of these, approximately 87% to 91% are estimated to have type 2 DM (T2DM) in high-income countries.1 In Spain, data from The Di@bet.es Study, a national, cross-sectional, population-based survey conducted in 2009–2010, showed that overall prevalence of DM (adjusted for age and sex) was 13.8%, of which about half had unknown diabetes.4

Most recent data published by the Spanish Ministry of Health ranked diabetes as the 9th health problem most frequently attended to in public primary care centres in patients older than 15 years and as the 4th when only population older than 64 years was considered, with a rate of 197 cases/per 1000 habitants assigned to the primary care level.5 DM was the 10th most common cause of mortality in both sexes, and diabetic patients reported worse QoL than the general population according to EQ-5D-5L scores.5,6 Data from the PANORAMA study, a cross-sectional observational study including Spanish patients, also showed how QoL is even poorer with the presence of other complications and poor glycaemic control.7

The general objectives of the treatment of diabetes are to avoid acute decompensation, prevent or delay the onset of late complications of the disease, reduce mortality and maintain a good QoL.8 The Spanish Ministry of Health, in compliance with World Health Organization (WHO) guidance, developed a Diabetes National Plan (DNP), which advocates an integrated approach, combining diabetes prevention, diagnosis and treatment. This includes management of not only glycaemia, but also of cardiovascular disease risk factors such as hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia with a healthy diet, recommended levels of physical activity and correct use of medicines as appropriately prescribed by a physician.9

To know how any intervention, including drugs, are working in real clinical practice is essential to improve the health care assistance continuously and to allocate the available limited health care resources better. In this sense, observational studies of clinical practice provide valuable information for physicians, payers and regulatory bodies during their corresponding decision-making processes.

Observational studies can confirm and extend the results obtained from randomised controlled trials to more diverse patient populations likely to be seen in clinical practice.10 Well-designed observational studies can identify clinically important differences among therapeutic options and provide data on long-term drug effectiveness and safety.10,11 Other interesting outcomes such as adherence, treatment persistence and patient-reported outcomes (PROs) (QoL, daily life functional capacity, treatment satisfaction, preferences, etc.) should be included in observational studies to add a broader and complementary analysis to the traditional clinical variables included in clinical trials.12

Specifically in diabetes, a position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) also have emphasised the significant need for high-quality, comparative effectiveness research, not only with focus on glycaemic control but also on costs, QoL and the prevention of morbid and life-limiting complications, especially cardio-vascular diseases.2

The aim of this systematic literature review (SLR) is to provide an overview of the Spanish research landscape of observational studies conducted with antidiabetic drugs in T2DM patients, published in the last 5 years, with special focus on the objectives, methodology and main research areas investigated. The main findings of this SLR can be useful for future researchers to identify the areas related with T2DM treatments that have not extensively studied and the variables not often included in previous research projects, in order to design new studies that add value to the available scientific knowledge so far. Likewise, this SLR seeks to identify the state of the art in observational research in diabetes in Spain as well as the different areas of improvement of future studies.

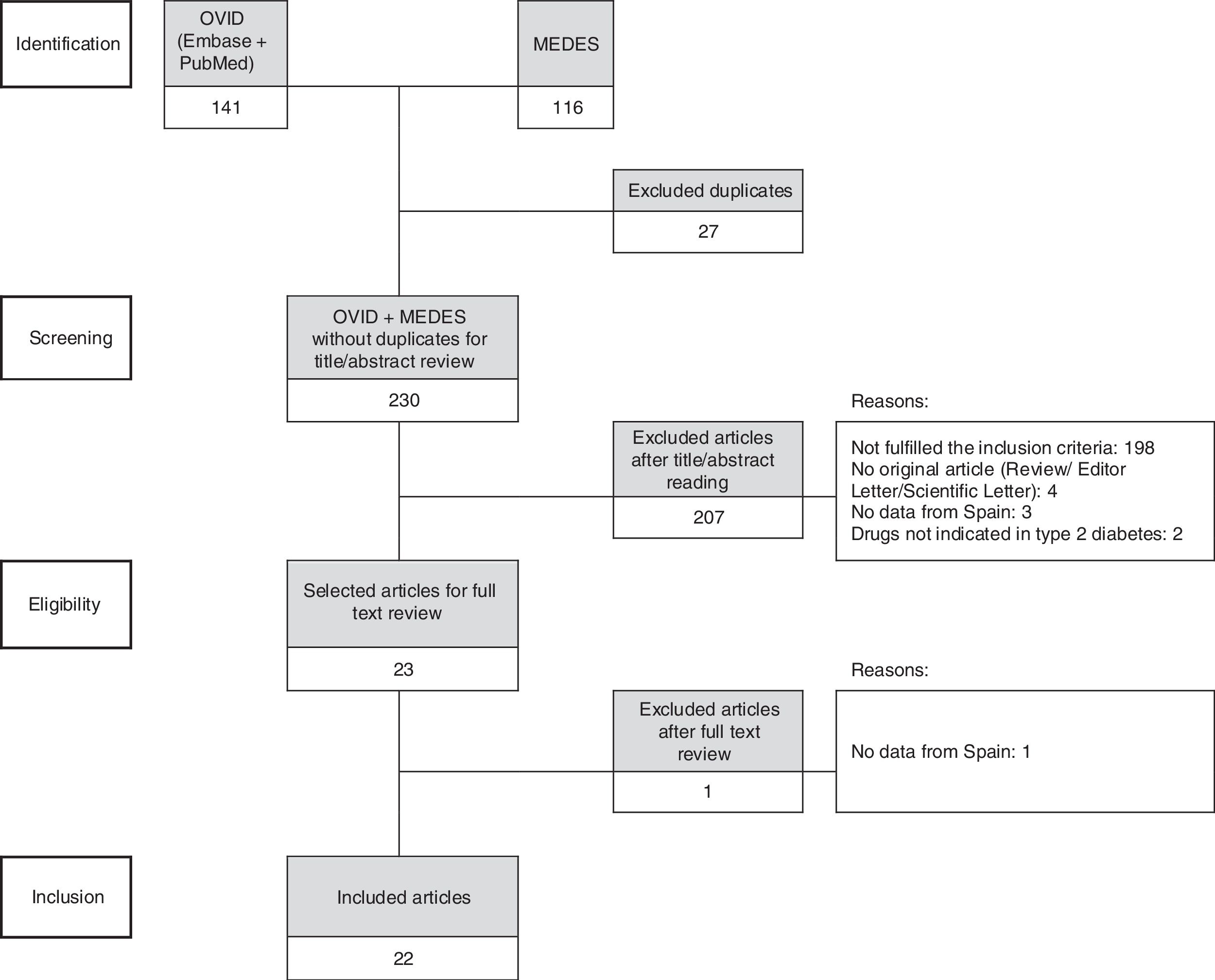

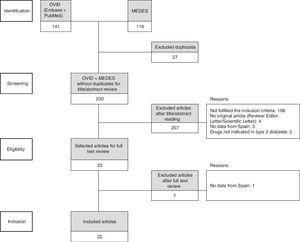

MethodsThis SLR was planned, conducted and reported in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Based on the title and abstract, two authors independently screened each retrieved record to identify potentially relevant articles for the full-text review. A third reviewer arbitrated in case of any doubt on eligibility.

Inclusion criteria included observational studies of T2DM patients conducted in Spain published between January 2012 and April 2017, in Spanish or English languages. To be included, studies had to assess at least one variable related to antidiabetic drug/s (i.e., effectiveness, safety, PROs outcomes, costs, treatment patterns, health resource consumption, etc.). Exclusion criteria included any narrative reviews, letters, editorials, and scientific letters. Further, articles about studies not conducted at Spanish sites, studies performed with drugs that were not indicated for T2DM, studies about comorbidities in diabetic patients such as diabetic eye or diabetic neuropathy, and studies that provided comparative economic outcomes based on simulation modelling and not on real-world data, were excluded.

A comprehensive search strategy was developed for OVID (Embase+Ovid MEDLINE[R]) and MEDES (Spanish bibliographic database in health sciences). The corresponding search summaries used are presented below.

OVID- 1.

(spain or espagne or espana or spain or espagne or espana or osasunbide* or osakidetza or insalud or sergas or catalunya or catalonia or catalogne or cataluna or catala or barcelon* or tarragona or lleida or lerida or girona or gerona or sabadell or hospitalet or l’hospitalet or valencia* or castello* or alacant or alicant* or murcia* or andalu* or sevill* or granad* or huelva or almeria or cadiz or jaen or malaga or (cordoba not argentin*) or extremadura or caceres or badajoz or madrid or castilla or salamanca or zamora or valladolid or segovia or soria or palencia or avila or burgos or (leon not (france or clermont or rennes or lyon or USA or mexic*)) or galicia or gallego or compostela or vigo or coruna or ferrol or orense or ourense or pontevedra or oviedo or gijon or asturia* or cantabr* or santander or vasco or euskadi or basque or bilbao or bilbo or donosti* or san sebastian or vizcaya or biscaia or guipuzcoa or gipuzkoa or alava or araba or vitoria or gazteiz or navarr* or nafarrona or pamplona or iruna or irunea or aragon* or zaragoza or teruel or huesca or mancha or ciudad real or albacete or cuenca or (toledo not (ohio or us or usa or OH)) or (guadalajara not mexic*) or balear* or mallorca or menorca or ibiza or eivissa or palmas or lanzarote or canari* or tenerife).mp. [mp=ti, ab, hw, tn, ot, dm, mf, dv, kw, fs, nm, kf, px, rx, ui, sy] (223635)

- 2.

exp longitudinal study/ or exp observational study/ or exp case control study/ or exp cross-sectional study/ or exp cohort analysis/ or exp data collection method/ or exp observational method/ (4947131)

- 3.

exp *non insulin dependent diabetes mellitus/ (203579)

- 4.

1 and 2 and 3 (714)

- 5.

not clinical trial/ (668)

- 6.

limit 5 to (conference abstract or conference paper or conference proceeding or “conference review”) [Limit not valid in Ovid MEDLINE(R); records were retained] (414)

- 7.

not 6 (254)

- 8.

limit 7 to yr=“2012 -Current” (159)

- 9.

remove duplicates from 8 (141)

{lmts}a2012[año_publicación]: 2017[año_publicación]{/lmts}((((((((“observacional”[título/resumen/palabras_clave]) OR “longitudinal”[título/resumen/palabras_clave]) OR “observacional”[título/resumen/palabras_clave]) OR “cohortes”[título/resumen/palabras_clave]) OR “caso-control”[título/resumen/palabras_clave]) OR “caso control”[título/resumen/palabras_clave]) OR “transversal”[título/resumen/palabras_clave])) AND ((“Diabetes mellitus no insulino-dependiente@319”[id_palabras_clave]) OR (“diabetes tipo 2”[título]) OR (“diabetes tipo ii”[título]) OR (“diabetes no insulinodependiente”[título]) OR (“diabetes no insulino-dependiente”[título]) OR (“diabetes no dependiente de insulina”[título]))

Reviewers extracted information from each of the selected articles to describe their main methodological characteristics (design, number of patients, duration of follow-up, time frame, environment, sample description, treatment studies and main objective/s, etc.), the type of variables reported as primary or secondary objectives (effectiveness, PROs, health resource use, costs, treatment patterns, etc.) and the available information about ethical and compliance disclosures.

The aggregated information of all the studies was synthesised to show a better overview of the most common designs, characteristics and areas of interest, presenting mean values and percentages of the total number of selected studies.

ResultsThe search strategy unveiled 230 references, of which 22 articles, corresponding to 20 studies, were included in the analysis after the systematic review process (Fig. 1).

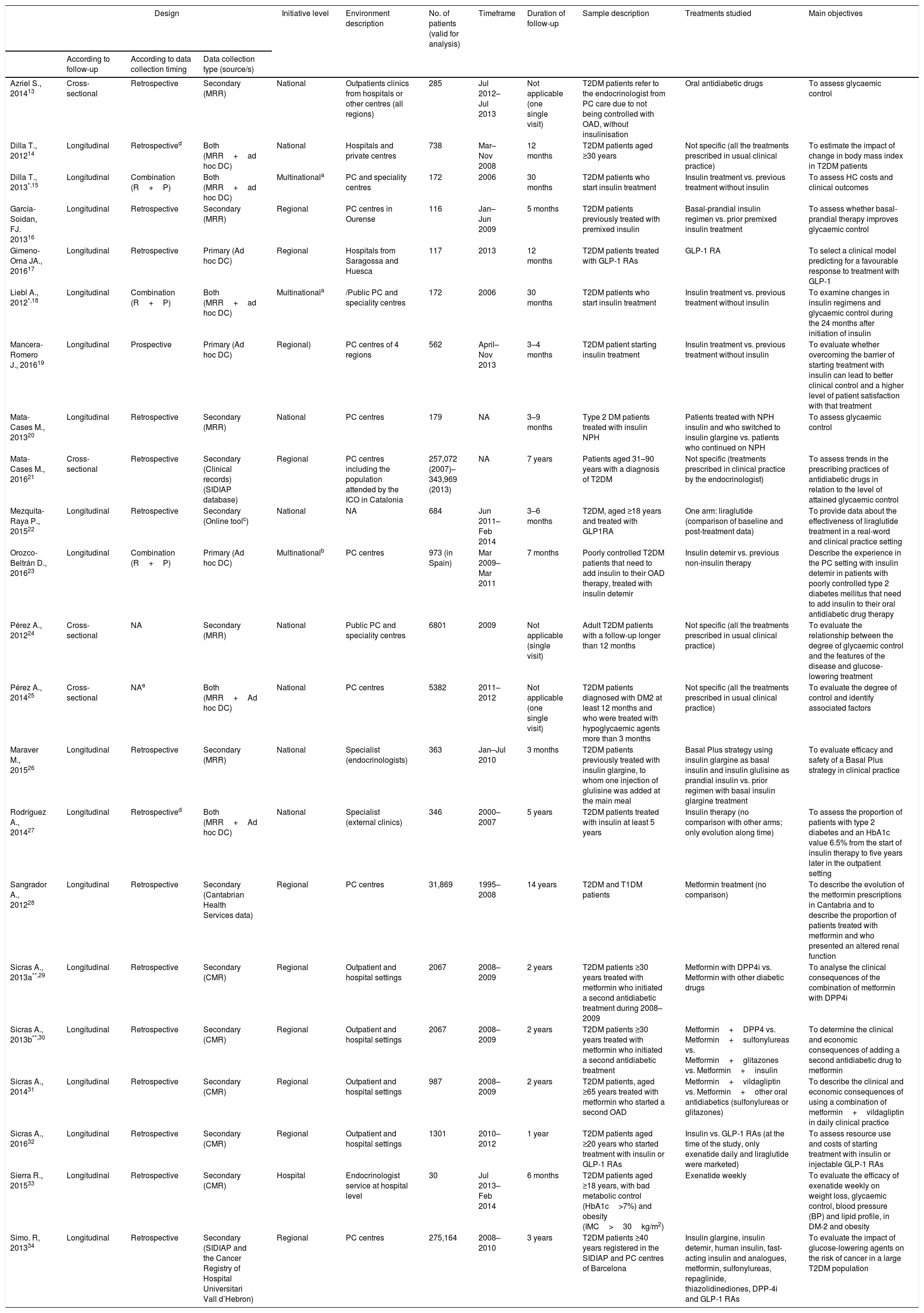

Methodological characteristics of the studiesTable 1 describes the design, objectives and main characteristics of each of the studies included in the review; Table 2 summarises their methodological characteristics jointly to provide an overview of the most frequent.13–34

Design and main characteristics of the studies included in the systematic literature review.

| Design | Initiative level | Environment description | No. of patients (valid for analysis) | Timeframe | Duration of follow-up | Sample description | Treatments studied | Main objectives | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| According to follow-up | According to data collection timing | Data collection type (source/s) | |||||||||

| Azriel S., 201413 | Cross-sectional | Retrospective | Secondary (MRR) | National | Outpatients clinics from hospitals or other centres (all regions) | 285 | Jul 2012–Jul 2013 | Not applicable (one single visit) | T2DM patients refer to the endocrinologist from PC care due to not being controlled with OAD, without insulinisation | Oral antidiabetic drugs | To assess glycaemic control |

| Dilla T., 201214 | Longitudinal | Retrospectived | Both (MRR+ad hoc DC) | National | Hospitals and private centres | 738 | Mar–Nov 2008 | 12 months | T2DM patients aged ≥30 years | Not specific (all the treatments prescribed in usual clinical practice) | To estimate the impact of change in body mass index in T2DM patients |

| Dilla T., 2013*,15 | Longitudinal | Combination (R+P) | Both (MRR+ad hoc DC) | Multinationala | PC and speciality centres | 172 | 2006 | 30 months | T2DM patients who start insulin treatment | Insulin treatment vs. previous treatment without insulin | To assess HC costs and clinical outcomes |

| García-Soidan, FJ. 201316 | Longitudinal | Retrospective | Secondary (MRR) | Regional | PC centres in Ourense | 116 | Jan–Jun 2009 | 5 months | T2DM patients previously treated with premixed insulin | Basal-prandial insulin regimen vs. prior premixed insulin treatment | To assess whether basal-prandial therapy improves glycaemic control |

| Gimeno-Orna JA., 201617 | Longitudinal | Retrospective | Primary (Ad hoc DC) | Regional | Hospitals from Saragossa and Huesca | 117 | 2013 | 12 months | T2DM patients treated with GLP-1 RAs | GLP-1 RA | To select a clinical model predicting for a favourable response to treatment with GLP-1 |

| Liebl A., 2012*,18 | Longitudinal | Combination (R+P) | Both (MRR+ad hoc DC) | Multinationala | /Public PC and speciality centres | 172 | 2006 | 30 months | T2DM patients who start insulin treatment | Insulin treatment vs. previous treatment without insulin | To examine changes in insulin regimens and glycaemic control during the 24 months after initiation of insulin |

| Mancera-Romero J., 201619 | Longitudinal | Prospective | Primary (Ad hoc DC) | Regional) | PC centres of 4 regions | 562 | April–Nov 2013 | 3–4 months | T2DM patient starting insulin treatment | Insulin treatment vs. previous treatment without insulin | To evaluate whether overcoming the barrier of starting treatment with insulin can lead to better clinical control and a higher level of patient satisfaction with that treatment |

| Mata-Cases M., 201320 | Longitudinal | Retrospective | Secondary (MRR) | National | PC centres | 179 | NA | 3–9 months | Type 2 DM patients treated with insulin NPH | Patients treated with NPH insulin and who switched to insulin glargine vs. patients who continued on NPH | To assess glycaemic control |

| Mata-Cases M., 201621 | Cross-sectional | Retrospective | Secondary (Clinical records) (SIDIAP database) | Regional | PC centres including the population attended by the ICO in Catalonia | 257,072 (2007)– 343,969 (2013) | NA | 7 years | Patients aged 31–90 years with a diagnosis of T2DM | Not specific (treatments prescribed in clinical practice by the endocrinologist) | To assess trends in the prescribing practices of antidiabetic drugs in relation to the level of attained glycaemic control |

| Mezquita-Raya P., 201522 | Longitudinal | Retrospective | Secondary (Online toolc) | National | NA | 684 | Jun 2011–Feb 2014 | 3–6 months | T2DM, aged ≥18 years and treated with GLP1RA | One arm: liraglutide (comparison of baseline and post-treatment data) | To provide data about the effectiveness of liraglutide treatment in a real-word and clinical practice setting |

| Orozco-Beltrán D., 201623 | Longitudinal | Combination (R+P) | Primary (Ad hoc DC) | Multinationalb | PC centres | 973 (in Spain) | Mar 2009–Mar 2011 | 7 months | Poorly controlled T2DM patients that need to add insulin to their OAD therapy, treated with insulin detemir | Insulin detemir vs. previous non-insulin therapy | Describe the experience in the PC setting with insulin detemir in patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus that need to add insulin to their oral antidiabetic drug therapy |

| Pérez A., 201224 | Cross-sectional | NA | Secondary (MRR) | National | Public PC and speciality centres | 6801 | 2009 | Not applicable (single visit) | Adult T2DM patients with a follow-up longer than 12 months | Not specific (all the treatments prescribed in usual clinical practice) | To evaluate the relationship between the degree of glycaemic control and the features of the disease and glucose-lowering treatment |

| Pérez A., 201425 | Cross-sectional | NAe | Both (MRR+Ad hoc DC) | National | PC centres | 5382 | 2011–2012 | Not applicable (one single visit) | T2DM patients diagnosed with DM2 at least 12 months and who were treated with hypoglycaemic agents more than 3 months | Not specific (all the treatments prescribed in usual clinical practice) | To evaluate the degree of control and identify associated factors |

| Maraver M., 201526 | Longitudinal | Retrospective | Secondary (MRR) | National | Specialist (endocrinologists) | 363 | Jan–Jul 2010 | 3 months | T2DM patients previously treated with insulin glargine, to whom one injection of glulisine was added at the main meal | Basal Plus strategy using insulin glargine as basal insulin and insulin glulisine as prandial insulin vs. prior regimen with basal insulin glargine treatment | To evaluate efficacy and safety of a Basal Plus strategy in clinical practice |

| Rodríguez A., 201427 | Longitudinal | Retrospectived | Both (MRR+Ad hoc DC) | National | Specialist (external clinics) | 346 | 2000–2007 | 5 years | T2DM patients treated with insulin at least 5 years | Insulin therapy (no comparison with other arms; only evolution along time) | To assess the proportion of patients with type 2 diabetes and an HbA1c value 6.5% from the start of insulin therapy to five years later in the outpatient setting |

| Sangrador A., 201228 | Longitudinal | Retrospective | Secondary (Cantabrian Health Services data) | Regional | PC centres | 31,869 | 1995–2008 | 14 years | T2DM and T1DM patients | Metformin treatment (no comparison) | To describe the evolution of the metformin prescriptions in Cantabria and to describe the proportion of patients treated with metformin and who presented an altered renal function |

| Sicras A., 2013a**,29 | Longitudinal | Retrospective | Secondary (CMR) | Regional | Outpatient and hospital settings | 2067 | 2008–2009 | 2 years | T2DM patients ≥30 years treated with metformin who initiated a second antidiabetic treatment during 2008–2009 | Metformin with DPP4i vs. Metformin with other diabetic drugs | To analyse the clinical consequences of the combination of metformin with DPP4i |

| Sicras A., 2013b**,30 | Longitudinal | Retrospective | Secondary (CMR) | Regional | Outpatient and hospital settings | 2067 | 2008–2009 | 2 years | T2DM patients ≥30 years treated with metformin who initiated a second antidiabetic treatment | Metformin+DPP4 vs. Metformin+sulfonylureas vs. Metformin+glitazones vs. Metformin+insulin | To determine the clinical and economic consequences of adding a second antidiabetic drug to metformin |

| Sicras A., 201431 | Longitudinal | Retrospective | Secondary (CMR) | Regional | Outpatient and hospital settings | 987 | 2008–2009 | 2 years | T2DM patients, aged ≥65 years treated with metformin who started a second OAD | Metformin+vildagliptin vs. Metformin+other oral antidiabetics (sulfonylureas or glitazones) | To describe the clinical and economic consequences of using a combination of metformin+vildagliptin in daily clinical practice |

| Sicras A., 201632 | Longitudinal | Retrospective | Secondary (CMR) | Regional | Outpatient and hospital settings | 1301 | 2010–2012 | 1 year | T2DM patients aged ≥20 years who started treatment with insulin or GLP-1 RAs | Insulin vs. GLP-1 RAs (at the time of the study, only exenatide daily and liraglutide were marketed) | To assess resource use and costs of starting treatment with insulin or injectable GLP-1 RAs |

| Sierra R., 201533 | Longitudinal | Retrospective | Secondary (CMR) | Hospital | Endocrinologist service at hospital level | 30 | Jul 2013–Feb 2014 | 6 months | T2DM patients aged ≥18 years, with bad metabolic control (HbA1c>7%) and obesity (IMC>30kg/m2) | Exenatide weekly | To evaluate the efficacy of exenatide weekly on weight loss, glycaemic control, blood pressure (BP) and lipid profile, in DM-2 and obesity |

| Simo. R, 201334 | Longitudinal | Retrospective | Secondary (SIDIAP and the Cancer Registry of Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron) | Regional | PC centres | 275,164 | 2008–2010 | 3 years | T2DM patients ≥40 years registered in the SIDIAP and PC centres of Barcelona | Insulin glargine, insulin detemir, human insulin, fast-acting insulin and analogues, metformin, sulfonylureas, repaglinide, thiazolidinediones, DPP-4i and GLP-1 RAs | To evaluate the impact of glucose-lowering agents on the risk of cancer in a large T2DM population |

CMR: computerised medical records; DC: data collection; ICO: Institut Català de la Salut; MRR: medical records review; OAD: oral antidiabetic drugs; PC: primary care; SIDIAP: System for the Development of Research in Primary Care; T1DP: type 1 diabetic patients; T2DP: type 2 diabetic patients. *Dilla T. and Liebl A. correspond to 2 complementary articles from the same study (one with international results and the other with Spanish results). **Sicras A. 2013a and Sicras A. 2013b are two references from the same study.

SOLVE study involved other countries: Germany, Canada, China, Spain, Israel, Italy, Poland, UK and Turkey.

eDiabetes-Monitor tool (designed for recording data on clinical characteristics of type 2 DM patients in clinical practice and for providing tools for the management of these patients).

Summary of the methodological characteristic of the studies included in the systematic literature review.

| Methodological characteristics | Results | Methodological characteristics | Results | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | References | N | % | References | ||

| Type of DM studied | Treatments studied | ||||||

| Type 2 | 21 | 95.5 | 13–27,29–34 | Not specific (all used in clinical practice) | 4 | 18.2 | 15,21,24,25 |

| Type 1 & 2 | 1 | 4.5 | 28 | Pharmacotherapeutical groups | |||

| Oral antidiabetic | 1 | 4.5 | 13 | ||||

| Design | Insulin | 7 | 31.8 | 14,16,18,19,27,30,32 | |||

| According to data collection timing | GLP-1 RA | 2 | 9.1 | 17,32 | |||

| Retrospective | 16 | 72.7 | 13,14,16,17,20–22,26–34 | DPP4i (alone or in combination) | 3 | 13.6 | 29,30,34 |

| Prospective | 1 | 4.5 | 19 | Specific drug/s | |||

| Combination (prospective+retrospective) | 3 | 13.6 | 15,18,23 | Metformin (alone or in combination) | 5 | 22.7 | 28–31,34 |

| Not applicable | 2 | 9.1 | 24,25 | Specific insulins | 4 | 18.2 | 16,23,26,34 |

| According to the follow up | Specific GLP-1 RA | 2 | 9.1 | 22,33 | |||

| Longitudinal | 18 | 81.8 | 14–20 | Others (sulfonylureas, glitazones, etc.) | 3 | 13.6 | 30,31,34 |

| Cross-sectional | 4 | 18.2 | 13,21,24,25 | ||||

| According source of data types | Number of arms/groups & Comparison analysis | ||||||

| Primary data collection | 3 | 13.6 | 17,19,23 | No specific arms & No comparison | 5 | 22.7 | 13,14,21,24,25 |

| Secondary use of data | 14 | 63.6 | 13,16,20–22,24,26,28–34 | One arm & No comparison arm | 5 | 22.7 | 17,22,27,28,33 |

| Both | 5 | 22.7 | 14,15,18,25,27 | One arm & Comparison with previous treatment. | 6 | 27.3 | 15,16,18,19,23,26 |

| Two arms & Compared | 4 | 18.2 | 20,29,31,32 | ||||

| Setting | Four arms & Compared | 1 | 4.5 | 30 | |||

| Multinational | 3 | 13.6 | 15,18,23 | 10 arms & Comparison vs. previous treatment | 1 | 4.5 | 34 |

| National | 10 | 45.5 | 13,14,16,20–22,24–27 | ||||

| Regional (1–4 regions involved) | 8 | 36.4 | 17,19,28–32,34 | Type of statistical analysis | |||

| Hospital | 1 | 4.5 | 33 | Descriptive | 5 | 22.7 | 13,18,21,27,28 |

| Descriptive & Exploratory | 2 | 9.1 | 15,23 | ||||

| Research environment | Analytic | 15 | 68.2 | 14,16,17,19,20,22,24–26,29–34 | |||

| Primary care (PC) | 7 | 31.8 | 16,19–21,25,28,34 | ||||

| Speciality care (SC) | 5 | 22.7 | 13,14,17,26,27 | Ethical committee approval | |||

| Both PC and SC | 9 | 40.9 | 13,15,18,23,24,29–32 | Yes | 15 | 68.2 | 14–16,18–20,22–27,30,32,34 |

| NA | 1 | 4.5 | 22 | NA | 7 | 31.8 | 13,17,21,28,29,31,33 |

| Follow-up durationa | Informed consent disclosure | ||||||

| 3–12 months | 12 | 66.7 | 14–20,22,23,26,32,33 | Yes | 13 | 59.1 | 13–15,18,20,22,23,25–27,31,32 |

| 2–5 years | 5 | 27.8 | 27–31 | No | 2 | 9.1 | 17,34 |

| 14 years | 1 | 5.6 | 28 | NA | 7 | 31.8 | 20,28–33 |

| Author's conflict of interest disclosure | |||||||

| Minimum age to participate in the study | Conflict declared | 12 | 54.5 | 13–15,18,20,22,23,25–27,31,32 | |||

| ≥18 years | 10 | 45.5 | 15,16,18–20,22,24–26,33 | No conflict to declare | 6 | 27.3 | 16,17,19,21,29,30 |

| 20–31 | 6 | 27.3 | 14,21,27,29,30,32 | NA | 4 | 18.2 | 24,28,33,34 |

| ≥40 | 2 | 9.1 | 13,34 | ||||

| ≥65 | 1 | 4.5 | 31 | Founding sources | |||

| Not specified | 3 | 13.6 | 17,23,28 | Pharmaceutical companies | 16 | 72.7 | 13–15,18–21,23–27,29–32 |

| Medical Societies | 1 | 4.5 | 22 | ||||

| NA | 5 | 22.7 | 16,17,28,33,34 | ||||

NA: not applicable; MRR: medical records review.

All the studies focused exclusively on adult T2DM, except one that included type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) patients.28 Around 82% of the studies employed a longitudinal study design, enabling follow-up of patients over a period ranging from a few months to a maximum period of 14 years, in the study of Sangrador et al., about the evolution of metformin prescriptions between 1995 and 2008.28

The majority of studies collected data retrospectively (72.7%),13,14,16,17,20–22,26–34 while a few used either prospective (4.5%)19 or a combination of retrospective and prospective study designs (13.6%).15,18,23 Most studies were based on secondary use of data (medical records review, registries or computerised database/tools) (63.6%), whereas 8 studies involved primary data collection (13.6% only primary17,19,23 and 22.7% both primary and secondary).14,15,18,25,27

Three of the studies (13.6%) were multinational initiatives15,18,23 with the participation of Spanish centres; while the rest of the studies were Spanish initiatives, conducted at regional or national level (45.5%16,17,19,28–32,34 and 36.4%, respectively13,14,20–22,24–27).

The mean number of patients investigated per study was 1266 (min: 30; max: 6801) when their design involved primary data collection or medical record review; this number increased to 109,226 (min: 987; max: 343,969) when large databases or registries were used as main data sources. In 40.9% of the studies, data was collected at both primary and specialty care levels,13,15,18,23,24,29–32 whereas 31.8%16,19–21,25,28,34 and 22.7%13,14,17,26,27 of studies collected information exclusively at primary care or specialty level, respectively.

A diverse number of pharmacotherapeutical groups or specific drugs were investigated, although a total of 4 studies (18.2%) did not focus on any specific drug but, rather, on the treatment used in clinical practice.14,21,24,25 Pharmacotherapeutical groups most frequently studied were insulin (32%)15,16,18,19,27,30,32 and DPP4i (13.6%) 29,30,34; specific drugs were metformin (alone or in combination) 28,34 and specific insulins.16,23,26,34

Regarding statistical analysis designs, analytic design was employed most in the studies (68.2%),14,16,17,19,20,22,24–26,29–34 followed by descriptive analysis (22.7%)13,18,21,27,28 and descriptive plus exploratory design (9.1%).15,23 Most of the analytic studies (86.7%) described the potential bias that could have affected the obtained outcomes, and 46.7% of them used different statistical techniques to adjust the results by the potential confounding factors that could bias the results.

Specific information on the need to obtain approval by an ethical committee as well as patients’ informed consent was included in 68.2% of the articles.14–16,18–20,22–27,30,32,34 Authors’ conflict of interest statements were available in 81.8% of the articles. Founding sources came from pharmaceutical companies in 16 studies (72.7%); Eli Lilly and Company, Sanofi Aventis and Novartis Farmacéutica SA were the most more active in supporting these studies (25%, 25% and 19%, respectively, of the total studies funded by pharmaceutical companies).

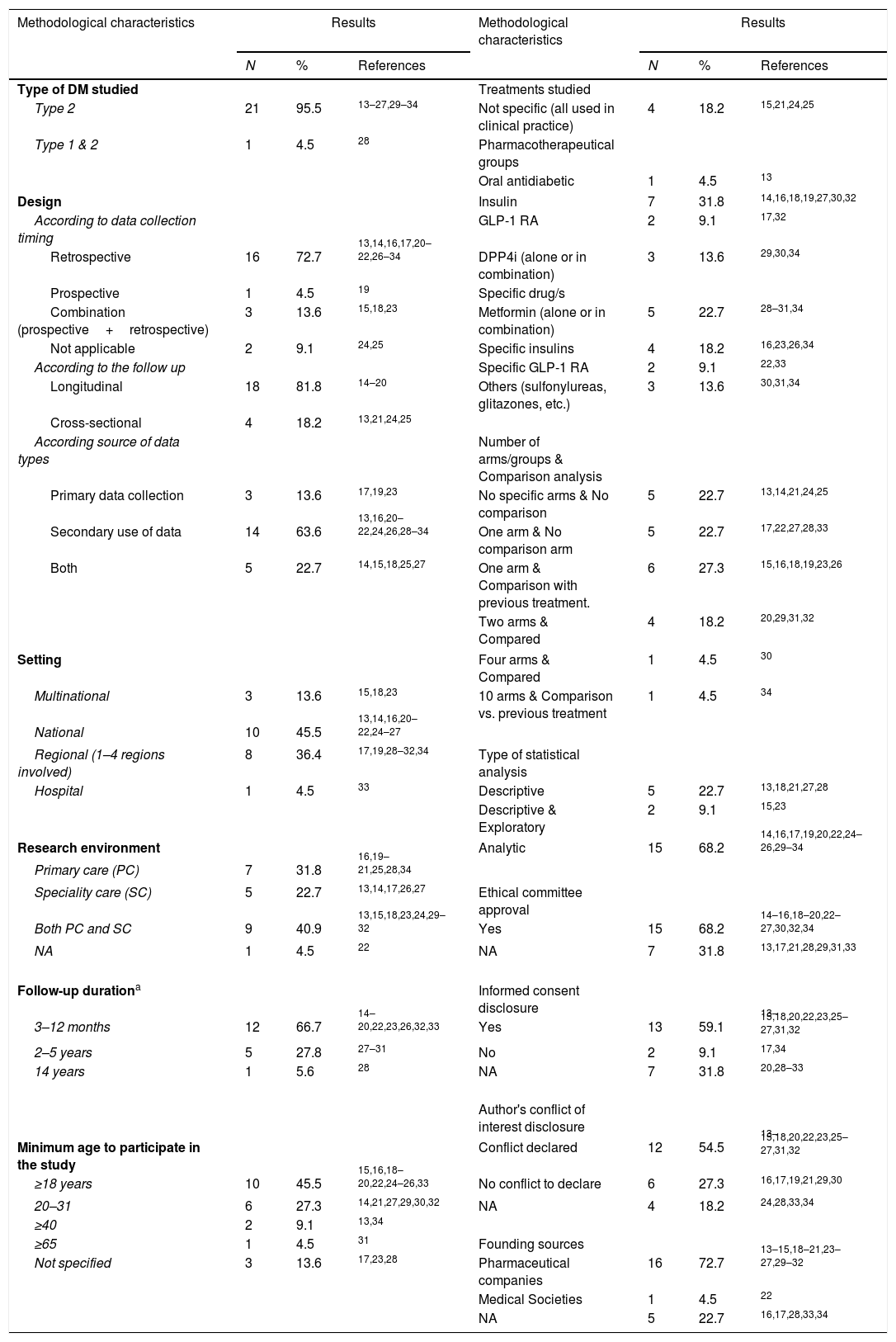

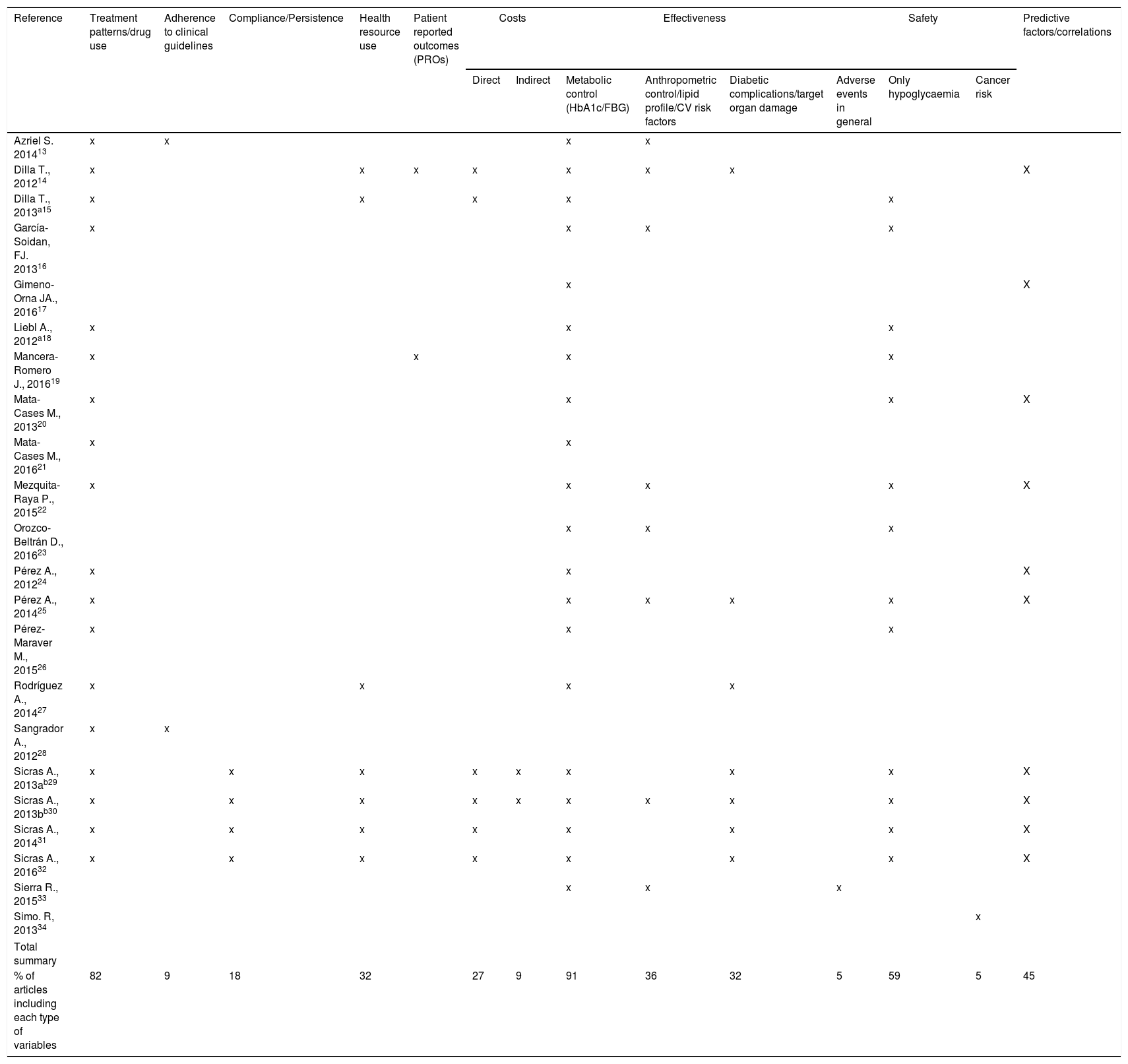

Main research areas identified in the studiesTable 3 represents in a visual way the main areas of research of each study, detailing the type of variables reported in each one (as primary or secondary objectives).

Summary of research areas included in each article.

| Reference | Treatment patterns/drug use | Adherence to clinical guidelines | Compliance/Persistence | Health resource use | Patient reported outcomes (PROs) | Costs | Effectiveness | Safety | Predictive factors/correlations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | Indirect | Metabolic control (HbA1c/FBG) | Anthropometric control/lipid profile/CV risk factors | Diabetic complications/target organ damage | Adverse events in general | Only hypoglycaemia | Cancer risk | |||||||

| Azriel S. 201413 | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Dilla T., 201214 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | X | ||||||

| Dilla T., 2013a15 | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| García-Soidan, FJ. 201316 | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Gimeno-Orna JA., 201617 | x | X | ||||||||||||

| Liebl A., 2012a18 | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Mancera-Romero J., 201619 | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Mata-Cases M., 201320 | x | x | x | X | ||||||||||

| Mata-Cases M., 201621 | x | x | ||||||||||||

| Mezquita-Raya P., 201522 | x | x | x | x | X | |||||||||

| Orozco-Beltrán D., 201623 | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Pérez A., 201224 | x | x | X | |||||||||||

| Pérez A., 201425 | x | x | x | x | x | X | ||||||||

| Pérez-Maraver M., 201526 | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Rodríguez A., 201427 | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Sangrador A., 201228 | x | x | ||||||||||||

| Sicras A., 2013ab29 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | X | |||||

| Sicras A., 2013bb30 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | X | ||||

| Sicras A., 201431 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | X | ||||||

| Sicras A., 201632 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | X | ||||||

| Sierra R., 201533 | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Simo. R, 201334 | x | |||||||||||||

| Total summary | ||||||||||||||

| % of articles including each type of variables | 82 | 9 | 18 | 32 | 27 | 9 | 91 | 36 | 32 | 5 | 59 | 5 | 45 | |

In the top five of the most studied variables are those related to effectiveness assessed according to glycaemic control (91%),13–27,29–33 treatment patterns and drug use (82%),13–16,18–22,24–32 safety (only focus on hypoglycaemia) (59%),15,16,18–20,22,23,25,26,29–32 the identification of effectiveness predictive factors or correlations (45%)14,17,20,22,24,25,29–32 and effectiveness according to other control measures such as anthropometric control/lipid profile or cardiovascular risk factors (36%).13,14,16,22,23,25,30,33 Data related to diabetic complications or organ damage was included in 32% of the articles14,25,27,29–32 as complementary information to other effectiveness data.

In terms of safety, only two studies showed data apart from hypoglycaemia-related variables: one presented recovered general adverse events information,33 and the other's main aim was to evaluate the impact of glucose-lowering agents in the risk of cancer in a large T2DM population.34

Information about health-resource use was reported in 7 studies (32%),14,15,27,29–32 and 6 out of these articles (27% of the total number of studies) also included their associated costs,14,15,29–32 including only direct costs in 4 of them and direct and indirect costs in 2 of them.

Compliance/persistence, adherence to clinical guidelines and patient-reported outcomes (PROs) were also reported in 18%,29–32 9%13,28 and 9%14,19 of the articles, respectively. PROs included treatment satisfaction and QoL assessments.14,18

DiscussionInformation extracted from this SLR gave us an overview of the Spanish research landscape of observational studies conducted with antidiabetic drugs in T2DM patients published in the last 5 years. The analysis of the main objectives and variables included in these studies, as well as their methodological characteristics, can help future researchers understand the current state of the art as well as further inform future clinical trial and observational designs.

The total number of articles included in this SLR was 22, which corresponds to 20 studies that were mostly Spanish initiatives at national/regional/hospital levels (86.4%), with financial support from pharmaceutical companies (72.7%) and published in national scientific journals (72.3%). The most frequent designs, according to data collection, follow-up and data sources employed, were retrospective (72.7%) and longitudinal (81.8%) and based on secondary data collection (63.6%). These types of studies are faster, generally less expensive and require a simpler approval process than studies that recover primary data prospectively,35 reasons that may explain their high use.

The full implementation of the electronic medical record and the development and better integration of electronic management databases will allow an even greater use of a research design that provides data from large and diverse populations and therefore has greater external validity than controlled clinical trials. However, to study the variables that are not routinely collected in these systems, as for example many PROs, other types of designs are needed that involve the collection of primary data, either cross-sectionally or prospectively. Our SLR found that 36.4% of the studies included any type of primary data collection (alone or together with the collection of secondary data), and 18.2% collected data prospectively.

Regarding the treatments studied, insulins are the most studied group of drugs, if we take into account that 18.2% of the studies focused on specific insulins and 31.8% studied them as a therapeutic group. Probably the study of the most recent therapeutic groups, such as GLP-1RAs, DPP-4i and SGLT-2i, will increase as they remain longer in the market and more patients are treated. Recent clinical trials of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) and sodium glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors that showed encouraging cardiovascular outcomes in T2DM patients may trigger greater interest in investigations of these drugs in an observational setting.36

In our SLR, the comparative effectiveness data between different treatment arms was the main objective in only 5 articles (22.7%).20,29–32 The rest did not include comparative information, or the comparison only referred to previous treatments or baseline data. Analytic statistical designs were employed in 68.2% of the articles, whereas the rest were merely descriptive or exploratory. Among the studies that incorporated analytical statistical techniques, 46.7% used some kind of statistical methodology to adjust for confounding factors (mainly regression analyses) and 86.7% described potential bias in their discussion section. Observational studies are increasingly being used for comparative effectiveness research. These studies can have the greatest impact when randomised trials are not feasible or when randomised studies have not included the population or outcomes of interest. However, careful attention must be paid to study design to minimise the likelihood of selection biases. Analytic techniques, such as multivariable regression modelling, propensity score analysis, and instrumental variable analysis, also can be used to help address confounding.

The information extracted from the studies of the main research variables shows that the effectiveness data on metabolic control was the main objective in most of the articles. Other efficacy variables that were collected in a complementary manner, in approximately one third of the studies, were those related to anthropometric control, lipid profile, cardiovascular risk factors and diabetic complications or organ damage. In 45% of the studies, the identification of predictive or correlated factors with the outcome variables (mainly effectiveness) was also studied, which gives very useful information to identify patients who might benefit more from a determined treatment. Eighty-two percent of the articles also included a detailed description of patterns of treatments or drug use, useful information for payers and health care authorities.

PROs were only included in two articles. Observational studies can include a huge variety of PROs that can provide information to improve the quality and patient-centeredness of medical care. An interesting study from Franch-Nadal et al.,37 showed that patients and physicians demonstrate different views concerning all questions related to T2DM health status, diabetes management and treatment (information, recommendations, satisfaction, and preferences), so it is important to collect this type of variables.38 Recent technological developments that facilitate the electronic collection of PROs and linkage of PRO data with other types of variables will offer new opportunities to develop this research area.38

Few studies recorded adherence to the clinical practice guidelines and treatment compliance or persistence (9% and 18% respectively). Correct adherence to prescribed medication is crucial for the control of diabetes and related comorbidities.39 On the contrary, poor medication adherence is a significant barrier to achieving good clinical outcomes, and it is associated with increased morbidity, mortality, health care expenditure and hospital admissions.40 Because these variables have to be collected in real clinical practice, observational studies are particularly useful in this area of research.

Safety variables, although collected in 15 articles (68.2%), focused almost entirely on the information about hypoglycaemias, with the exception of one article that collected general adverse events and another that studied the possible risk of cancer related to the use of different drugs. Observational studies have been recognised as essential for investigating the safety profiles of medications, especially when the outcome of drug exposure is rare, delayed or observed in specific subgroups.41

Health care resources used and cost-related variables were included in approximately one third of the articles. Measuring efficiency over time is a critical element in improving the performance of health systems. Information about the use of health resources and their associated costs, along with outcome measurements, will ensure effective and efficient spending in health care budgets. The collection of indirect costs, together with direct cost, observed in two studies, allows a broader perspective analysis due to it takes into account cost for the society and not only for health care systems, Specific information on the approval of the study by an ethics committee, as well as the need or not to obtain an informed consent from the patient, was described in most of the articles; however, a percentage of them did not include this information. In accordance with Spanish legislation, all observational studies must be approved by a committee independently of their design, so it would be advisable to indicate whether this step was completed.35 With respect to informed consent, we could assume that when this information is not available it was because it was not mandatory to collect it, but we cannot really affirm it with certainty. If this were the case, it would also be advisable to make it explicit and include the corresponding justification.

With the information on the financing and conflicts of interest of the authors, a similar case is given. It was reported mostly, but in some cases, it was not available. This information should be clearly described even in those cases in which there was no external funding source or when there is no conflict of interest.

Some inherent limitations to this systematic review should be considered. The current review does not include any research activity, which was not published or not published as a full paper, such as a congress publication. In addition, the quality of the studies was not evaluated because the different designs and objectives of the studies found in this SLR made it very difficult to use any quality assessment tool that allows presenting the results in a useful and comparative way. Most of the questionnaires designed for assessing quality of observational studies are developed for comparative research between different treatment arms or specific for some types of specific design42–44; which make it difficult to be applied to this work.

To summarise, well-designed observational studies using data from large populations can address some of the questions clinical trials cannot. Results from this SLR showed that diverse observational study designs and methodologies have been used to study antidiabetic drugs in T2DM patients in the last 5 years in Spain. It would be interesting if future studies focused on the less-studied research areas to date, as, for instance, PROs, comparative effectiveness, adherence and persistence, general safety information, costs and so on, especially with the new treatments coming to the market. The improvement of the correct reporting of finance sources, authors’ conflicts of interest and ethics compliance should also be recommended to ensure the credibility of the findings of these studies.

ContributionsAll the authors (SD, TD and JR) have been involved in the different phases of the study (concept and design, data extraction, data analysis and interpretation of the results) as well as in the redaction of the present manuscript (drafting and final approval).

FundingThis study has been funded by Eli Lilly and Company, Spain.

Conflict of interestThe authors of this article (SD, TD and JR) are employees of Eli Lilly and Company (Spain) and hold Eli Lilly and Company shares.