Adherence to somatotropin treatment is associated with increased growth velocity and improved adult height. The purpose of this study is to determine the adherence of patients undergoing treatment with an electronic device and its relationship with different variables (age, gender, duration of treatment, diagnosis, height, and growth rate).

Material and methodsDescriptive, longitudinal and retrospective study of children less than 14 years of age undergoing treatment with somatotropin administered with the Easypod® electronic device in the Paediatric Endocrinology Outpatient Clinic of the General University Hospital of Ciudad Real, Spain. Adherence was monitored for 12 months and was defined according to the equation: (days administered at the prescribed dose/prescribed days)×100. The data analysis was performed using SPSS software.

ResultsData were collected from 30 patients, with a predominance of males (57%), a mean age of 6.09 years, with 51% of children less than 5 years old. The most common reasons for the treatment were: small for gestational age (55%) and growth hormone deficiency (38%). The mean duration of treatment was 4.3 years (3.6–5). A mean adherence of 92.3% (87.7–96.9) was observed, and there was a significant correlation with age (Pearson R=−0.384, P=0.03), and duration of treatment (Pearson R=−0.537; P=0.003).

ConclusionsThe adherence in our patients with electronic device is high (92.3%), and is inversely associated with age and duration. The use of electronic devices allows monitoring of therapeutic compliance, which affects the optimisation of treatment.

La adherencia al tratamiento con somatotropina se relaciona con el aumento de la velocidad de crecimiento y la mejora de la talla adulta. El objeto de este estudio es conocer la adherencia de pacientes en tratamiento con dispositivo electrónico y determinar la relación con diferentes variables (edad, sexo, duración del tratamiento, diagnóstico, talla y velocidad de crecimiento).

Material y métodosEstudio descriptivo, longitudinal y retrospectivo de menores de 14 años de la consulta de Endocrinología Pediátrica del Hospital General Universitario de Ciudad Real, en tratamiento con somatotropina administrada con el dispositivo electrónico Easypod®. Se realiza seguimiento de la adherencia durante 12 meses. Se define adherencia según la fórmula: (días administrados a la dosis prescrita/días prescritos)×100. El análisis de los datos se realizó con el software SPSS.

ResultadosSe recogió a 30 pacientes: predominio varones (57%), edad media 6,09 años, menores de 5 años el 51%. Las causas más frecuentes de tratamiento: pequeño para la edad gestacional (55%) y déficit de hormona de crecimiento (38%). Tiempo medio de tratamiento 4,3 años (3,6-5). Se evidenció una adherencia media del 92,3% (87,7-96,9), observándose una correlación significativa con la edad (R de Pearson=–0,384; p=0,03) y la duración del tratamiento (R de Pearson=–0,537; p=0,003).

ConclusionesLa adherencia en nuestros pacientes con dispositivo electrónico es alta (92,3%), relacionándose inversamente con la edad y la duración del tratamiento. El uso de dispositivos electrónicos permite un seguimiento del cumplimiento terapéutico, lo que repercute en la optimización del tratamiento.

Non-adherence to somatotropin therapy is the main cause of poor response to treatment.1 Adherence is particularly relevant in this type of therapy, because it involves daily dosing that often lasts for years; is complex to administer; and is not related to any life-threatening condition. As a result, both patients and relatives may lack motivation regarding correct adherence to therapy. Nevertheless, treatment adherence is essential, because it is correlated to increased growth rate and secondarily to improved height in adult life.2,3

The identification of non-compliance in somatotropin treatment has a significant clinical and cost impact, since it allows for differentiation between non-responders and non-compliers, so avoiding unnecessary tests, and allowing for dose optimization.1

The data published to date on adherence are very heterogeneous, largely because of the variability in the data collection methodology used and the different types of devices employed for treatment administration. Electronic devices for the administration of somatotropin have been available since 2007. Compared to other methods such as conventional or prefilled syringes, electronic devices have been associated with improved treatment compliance thanks to their convenience and easy use. They moreover allow for a more objective evaluation of adherence.4

Therefore, the objective of this study was to assess adherence in a group of patients treated with somatotropin administered using an electronic device, and to determine the relationship between adherence and variables, such as age, gender, treatment duration, diagnosis, degree of height impairment, and growth rate. It should be noted that very few publications on treatment adherence have been published since the introduction of these electronic devices on the market, and no studies have been made in our setting with one particular device as in our case.

Material and methodsA retrospective, longitudinal descriptive study was carried out. We included patients under 14 years of age from the Pediatric Endocrinology Clinic of Hospital General Universitario de Ciudad Real (Ciudad Real, Spain), treated with somatotropin administered using the Easypod® device (Saizen Easypod System, Merck Laboratory). The patients were selected through non-probability consecutive sampling.

Data corresponding to the period between May 2015 and May 2016 were analyzed. Patients who had not completed one year of treatment or who had completed it before 2015 were excluded, as were patients not falling within the health area of Ciudad Real, in which the follow-up of the device was made from the pharmacy of their hospital of origin. The following data were collected for each patient: gender, age (expressed in years with decimal places and stratified as ≤5 years, 6–10 years, and 11–14 years), reason for starting treatment according to the criteria established by the Growth Hormone Advisory Committee of the Spanish Ministry of Health (small for gestational age, growth hormone deficiency, Turner syndrome, chronic renal failure, Prader–Will syndrome and SHOX gene alterations), height and growth rate. The latter parameters were expressed as standard deviations from the mean, according to the reference values of the Spanish growth study (2010).5

Growth data were collected at the start and end of the study period, covering a total of one year. A rigid wall stadiometer reading from 60 to 200cm was used for measurements, with a precision of 0.1cm. Measurements were performed with the patient barefoot in direct contact with the floor, and with the head, shoulders, hips, and heels together and resting against the rigid part of the stadiometer.

Adherence data were obtained directly from the Easypod® device, which records the date and time of drug administration, the dose, the number of doses remaining in the cartridge, and the number of doses administered. The device was supplied by the hospital pharmacy, and prior to the start of treatment the patient and his/her relatives were instructed on how to use it, and their correct application of it checked before administration could be carried out at home. Device renewal and data download were performed by the same service on a monthly basis. Percentage adherence to treatment was calculated based on the formula: (days administered at the prescribed dose/days prescribed)×100. In order to qualitatively establish the degrees of adherence among the patients, and taking into account that the classifications published to date differ, we established the following categories: excellent adherence (>95%), good adherence (95–85%), fair adherence (85–75%), and poor adherence (<75%).

The data were analyzed using the SPSS version 19.0 statistical package. The results of the descriptive statistical study were reported using central frequency and dispersion statistics, with percentages and histogram representations. As regards the inferential statistical analysis, the Pearson correlation test (between quantitative variables) and the Mann–Whitney U-test (for the comparison of quantitative and qualitative variables) were used after checking for goodness of fit and normal distribution of the values using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The data were expressed as mean values with the corresponding 95% confidence interval (95%CI). Statistical significance was considered for P<0.05 in all cases.

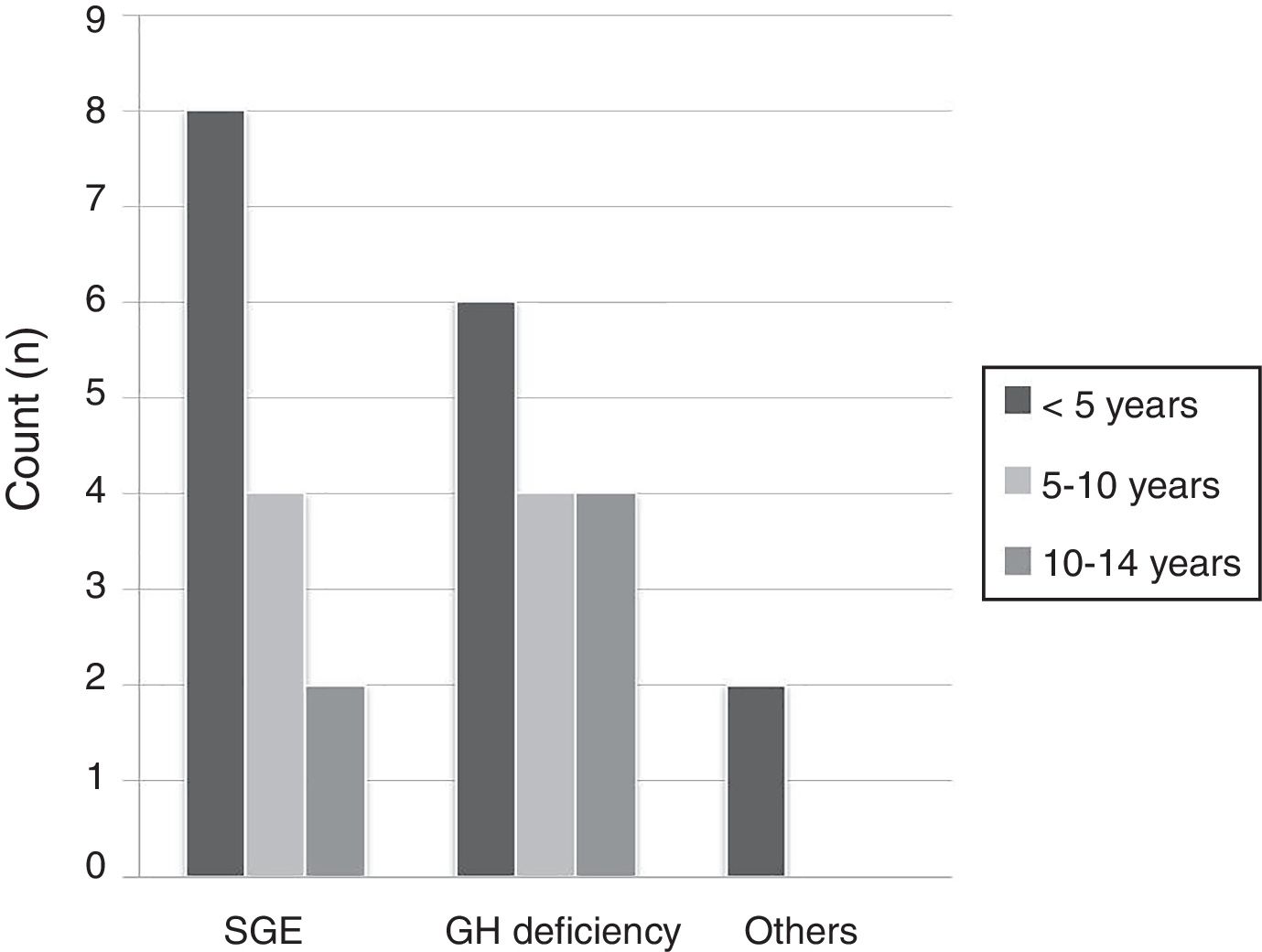

ResultsA total of 30 patients with a predominance of males (57%) and a mean age of 6.09 years (range 4.92–7.25) were included in the study. The group aged 5 years or younger was the largest (51%), followed by the group aged 6–10 years (28.5%) and the group aged 11–14years (20.5%). The most frequent causes for treatment were small size for gestational age (55%), growth hormone deficiency (38%), and Turner syndrome (7%), with a lower mean patient age in the first cause as compared to the second (5 versus 6.8years) (Fig. 1). As regards the auxological values, paired data analysis was performed, recording a mean height gain during the year of follow-up of 0.63 standard deviations (0.49–0.78).

The mean treatment time was 4.3 years (3.6–5). The mean adherence to therapy rate was 92.3% (87.7–96.9%). As regards the qualitative distribution of adherence, 60% of the patients were excellent compliers, 30% good compliers, 3.3% fair, and 6.7% poor compliers.

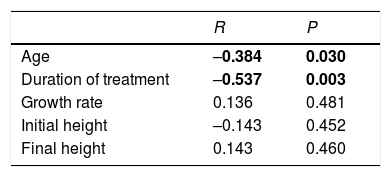

A significant negative correlation was observed between adherence and age and treatment duration. No significant relationship was found between adherence and height at the start and end of the study period, or between adherence and growth rate (Table 1). There were no differences in adherence between males and females (P=0.815), and the correlation between adherence and the different causes of treatment was likewise nonsignificant (P=0.085).

Correlations between adherence and the different quantitative variables studied.

| R | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | –0.384 | 0.030 |

| Duration of treatment | –0.537 | 0.003 |

| Growth rate | 0.136 | 0.481 |

| Initial height | –0.143 | 0.452 |

| Final height | 0.143 | 0.460 |

R: Pearson correlation coefficient.

P: statistical significance, P<0.05 (marked in boldface).

The adherence data published to date are highly variable, largely because of differences in the methodology used. Thus, in those studies including different devices and that collect adherence data indirectly through questionnaires targeted to patients or parents, a percentage of good compliers ranging from 48–78.7% was observed,3,6–10 this figure being much lower than that obtained in our study. The disadvantages of this method for measuring adherence are that it is conditioned by patient subjectivity and may be affected by memory bias. It has been estimated that these two factors may result in an overestimation of treatment adherence by up to 2.7%.4 On the other hand, greater compliance (between 87.5 and 92%) was observed in studies involving electronic devices, where adherence data are obtained directly from the device itself.4,11,12 These values are very similar to those recorded in our study. It has been seen that drug administration methods that are easier for the patient and cause less pain are associated with greater compliance.13–18 This represents another significant advantage of electronic devices with respect to the rest. Likewise, such devices may imply an extra motivation for the patient who is aware that adherence is being recorded objectively, and it can help differentiate between non-compliance as the cause of treatment failure and non-responders.

The various studies report heterogeneous results with regard to the relationship between the degree of adherence and other variables associated with treatment. Thus, some studies report improved compliance in males as compared to females,18 though this gender association has not been confirmed in other studies, including our own series.2,12,19 On analyzing age, poorer compliance was reported in different studies among older pediatric patients, particularly adolescents, as compared to younger children.2,10,12,13,20 This is consistent with our own findings. The above may be attributed to greater parental control over younger patients, as well as to the rejection of chronic medical treatments that characterize the adolescent stage. As in our series, adherence was seen to be lower in longer treatments.2,10,13,21 This may be related to diminished motivation over time, as well as to the rejection which sustained therapy over a period of years can cause, particularly among older patients. A positive correlation was observed between adherence and growth rate, and a negative association was recorded between adherence and the number of missed doses.18 Nevertheless, the association between adherence and growth rate was not found to be significant in our series. Lastly, no differences in compliance were recorded among the different indications of somatotropin therapy.12 However, because of the sample size and distribution of the different diagnoses, this analysis could only be made in our study in patients with growth hormone deficiency and a history of small size for gestational age, with no recovery of body height.

The identification of non-adherence to somatotropin therapy allows for the differentiation of non-responders from non-adherent patients. This in turn can help us to avoid performing of unnecessary complementary tests causing patient discomfort and increased economic costs. In this respect, it has been estimated that electronic devices increase adherence by 20% as compared to all other devices, which would allow for treatment optimization and cost savings ranging from 22 to 27%.1

The main limitation of this study is the absence of measurements of other variables that may also influence adherence to somatotropin therapy. One postulated parameter is the educational level of the parents. A higher educational level could imply a greater adherence due to increased awareness of the negative consequences of a lack of compliance with therapy.10 In this scenario early medical consultation is also more likely in the event of treatment-derived problems, which indirectly implies an early diagnosis of the possible negative consequences derived from therapy.16,19 Another conditioning factor may be patient information, and in this regard it has been reported that compliance is improved in children and parents who understand the disease, the use of the device, and the consequences of failure to administer the treatment.10,13,22

From the data obtained in our series it can be concluded that the use of electronic devices for somatotropin therapy is associated with very good adherence and allows objective and close monitoring of treatment compliance in these patients, which in turn could result in both clinical and economical benefits.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Arrabal Vela MA, García Gijón CP, Pascual Martin M, Benet Giménez I, Áreas del Águila V, Muñoz-Rodríguez JR, et al. Adherencia al tratamiento con somatotropina administrada con dispositivo electrónico. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2018;65:314–318.