Hypoglycemia in adults is a common adverse event in patients with treatment for diabetes mellitus; however, it is uncommon in individuals without it.1 We report the case of an adult female with severe hypoglycemia and a medical history of previous episodes of low serum glucose during fasting in the first months of age.

CaseA 34-year-old Hispanic female presented to our hospital with malaise, nausea, and vomiting during the last 3 days. Her medical history was relevant for several previous hospitalizations due to severe hypoglycemia during the newborn period and childhood, causing intellectual disability and recurrent epileptic seizures. She was treated during her childhood with valproic acid but with unknown adherence to treatment and irregular medical visits.

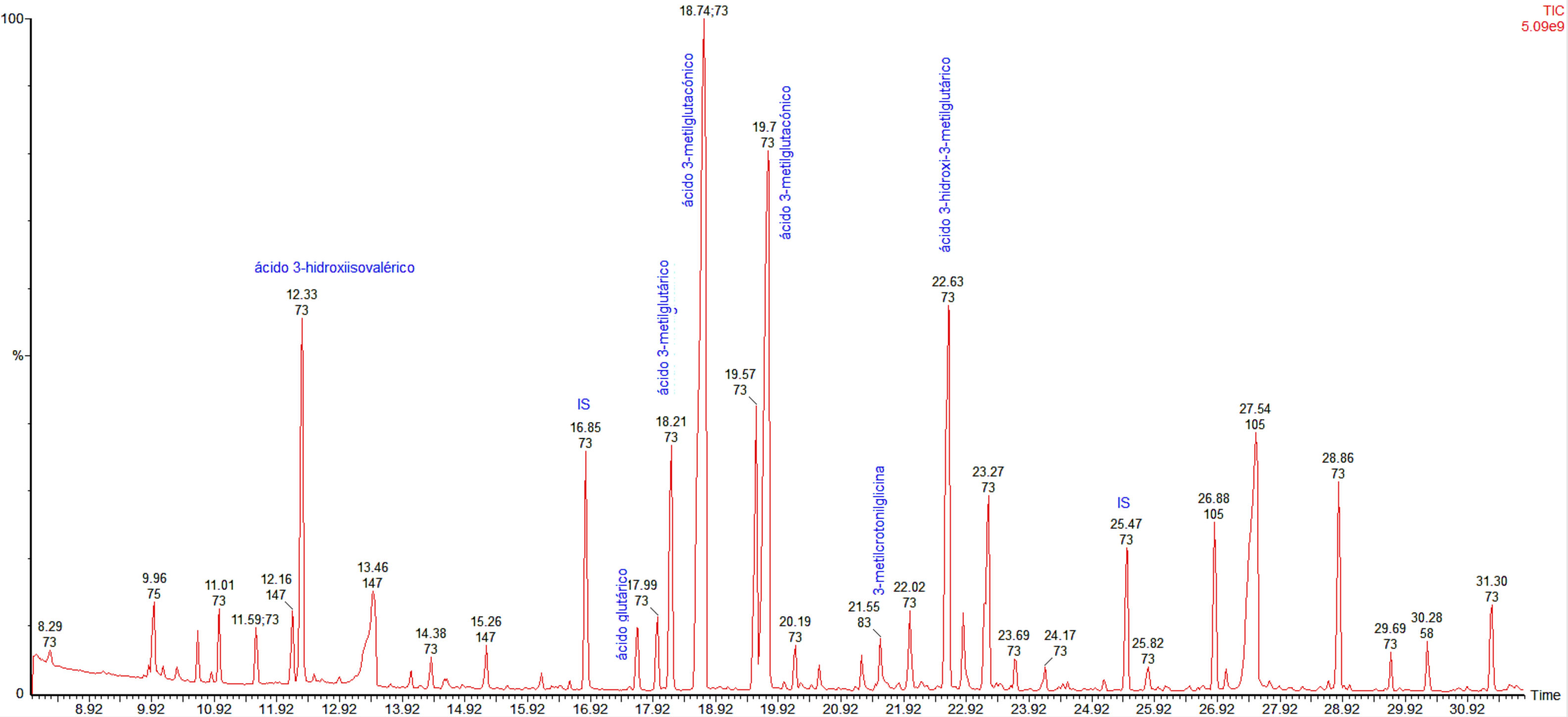

On initial examination, her blood pressure was 100/60mmHg, heart rate 90bpm, respiratory rate 18bpm. Her temperature was 98.0°F and oxygen saturation was 99% on room air. There were no other relevant findings. During the first minutes in the emergency room, she developed the first episode of severe hypoglycemia treated with intravenous 25g of 50% glucose with an adequate response. After that, multiple episodes of level 3 hypoglycemia (event characterized by altered mental and/or physical functioning that requires assistance from another person for recovery) were documented and a comprehensive diagnostic approach was started. Her laboratory tests were relevant for a pH 7.20, and an HCO3 10.6mEq/L, with normal urine dipstick results. A medical history of previous episodes of hypoglycemia during the first years of life and the presence of an anion gap metabolic acidosis were the main reasons for suspecting a genetic metabolic disease. In this respect, biochemical studies were performed showing an increased urinary level of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaric, 3-methylglutaconic, 3-methylglutaric and 3-hydroxyisovaleric acids (Fig. 1), which are diagnostic for 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A lyase deficiency.

DiscussionHypoglycemia in nondiabetic adults is an infrequent event that commonly requires a diagnostic approach only performed in those who present Whipple's triad.2 Physiological responses to hypoglycemia consist of decreased insulin secretion, and increased glucagon, epinephrine, cortisol and growth hormone secretion. These hormone changes prompt liver cells to engage all biochemical routes directed to the production and/or release of glucose. If these defenses fail to abort hypoglycemia, serum glucose levels will continue to fall.1 A large number of diseases can cause hypoglycemia in adults. However, in our patient, hypoglycemia was accompanied by a persistent increased anion gap metabolic acidosis, which is uncommon in endocrine diseases. In this respect, inborn errors of metabolism should be considered in the differential diagnosis because patients can have their first acute metabolic emergency later in life.

HMG-CoA lyase deficiency is a rare autosomal recessive disease caused by an error of ketone body and leucine metabolism, first described in 1976.3 HMG-CoA lyase deficiency is mainly diagnosed during the neonatal period and is fatal unless treated promptly.4 The disease has an estimated prevalence of less than 1 in 100,000 live births. This inborn error of metabolism is mainly characterized by an increased anion gap metabolic acidosis, hyperammonemia, hypoglycemia with no ketosis and elevation of the organic metabolites 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaric, 3-methylglutaconic, 3-methylglutaric, and 3-hydroxy-isovaleric acids in urine.5 In patients with HMG-CoA lyase deficiency, the main mechanism that produces fasting hypoglycemia is an excess of glucose use by the peripheral tissues because of the inability to synthesize ketone bodies or free fatty acids for oxidation, due to the shortfall of secondary carnitine.6 This deficit is the result of excess acyl-CoA, which after esterification to acyl-carnitine, is lost in the urine.6–8 The inadequate oxidation of free fatty acids is the reason for a lack of formation of ketone bodies. This also interferes with neoglucogenesis from protein and glycerol sources. During fasting, tissues consume glucose until glycogen stores are depleted and then symptoms appear as there is no new formation of glucose from other sources. The brain is especially affected because of its high metabolic rate. In consequence, ketonuria is not present in HMG-CoA lyase deficiency and this finding is helpful in its differentiation from other organic acidemias.

In a previous cohort of 37 patients with a diagnosis of HMG-CoA lyase deficiency, parental consanguinity was present in half of the patients5; however, this was not the case in our patient. Also, the median pH in this cohort was 7.21, similar to our case. In 84% of patients, the diagnosis was made within the first two years of life at a median age of six months. After the first year of life patients usually show a prolonged resistance to fasting and adults could be symptom free because they have greater glycogen stores, which allow longer periods of fasting before hypoglycemia occurs. This age group only has symptoms with prolonged fasting or vomiting. This was possibly the case in our patient who was diagnosed with HMG-CoA lyase deficiency during adulthood.

A definitive diagnosis is established with 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme-A lyase enzyme activity in cultured fibroblasts and lymphocytes. It is also diagnosed by the gas chromatography/mass spectrometer pattern of excreted organic acids in the urine. Long-term therapy consists of restriction of protein and fat intake and maintaining dietary supplementation with l-carnitine (75–100mg/kg/day). Frequent and severe acute metabolic acidosis reduce treatment success for the disease.9,10

In conclusion, inborn errors of metabolism should be suspected in adults when more frequent causes of hypoglycemia have been ruled out, especially when there is acidosis or other uncommon biochemical findings such as hyperammonemia. Previous episodes during infancy help suspect congenital causes to reach a prompt diagnosis and give appropriate therapy.

Conflict of interestNone declared.

We thank Sergio Lozano-Rodríguez, MD, for his critical review of the manuscript.