The term “glycosylated haemoglobin” (HbA1c) describes haemoglobin irreversibly bound to glucose through a non-enzymatic reaction.1,2 Its levels are measured to evaluate blood glucose control in patients with diabetes mellitus, as it reflects blood glucose in the past 120 days (corresponding to the half-life of erythrocytes).3 It is considered a useful marker for determining the risk and progression of chronic complications related to this disease.1,2 Various factors that might interfere with the reliability of HbA1c measurement have been reported,1,2 including different haemoglobin variants that may be responsible for falsely high or low HbA1c levels.3,4

We report the cases of two related patients with discrepant levels of both plasma and capillary blood glucose and HbA1c due to haemoglobin Himeji, a very rare, clinically silent haemoglobinopathy with approximately three times the glycosylation of haemoglobin A.5

The first case corresponds to a 39-year-old native of Portugal in follow-up for controlled HIV infection. He was on antiretroviral treatment with efavirenz, tenofovir and emtricitabine.

Routine testing revealed that the patient had high HbA1c levels yet normal plasma and capillary blood glucose levels. Hygiene and dietary measures were put in place immediately. The patient’s elevated HbA1c levels persisted, so treatment was started with metformin 850 mg every 12 h and the patient was referred to endocrinology. Prior laboratory tests had shown HbA1c levels of 12% (April 2015), 11.5% (January 2016), 11.8% (June 2016) and 11.9% (April 2018) with fasting glucose levels of 89 mg/dl, 96 mg/dl, 93 mg/dl and 99 mg/dl, respectively. Due to this incongruence, a decision was made to place a flash glucose monitor. This confirmed that the patient had blood glucose levels in a normal range. His serial complete blood count and clinical chemistry, including kidney and liver function tests, were also normal.

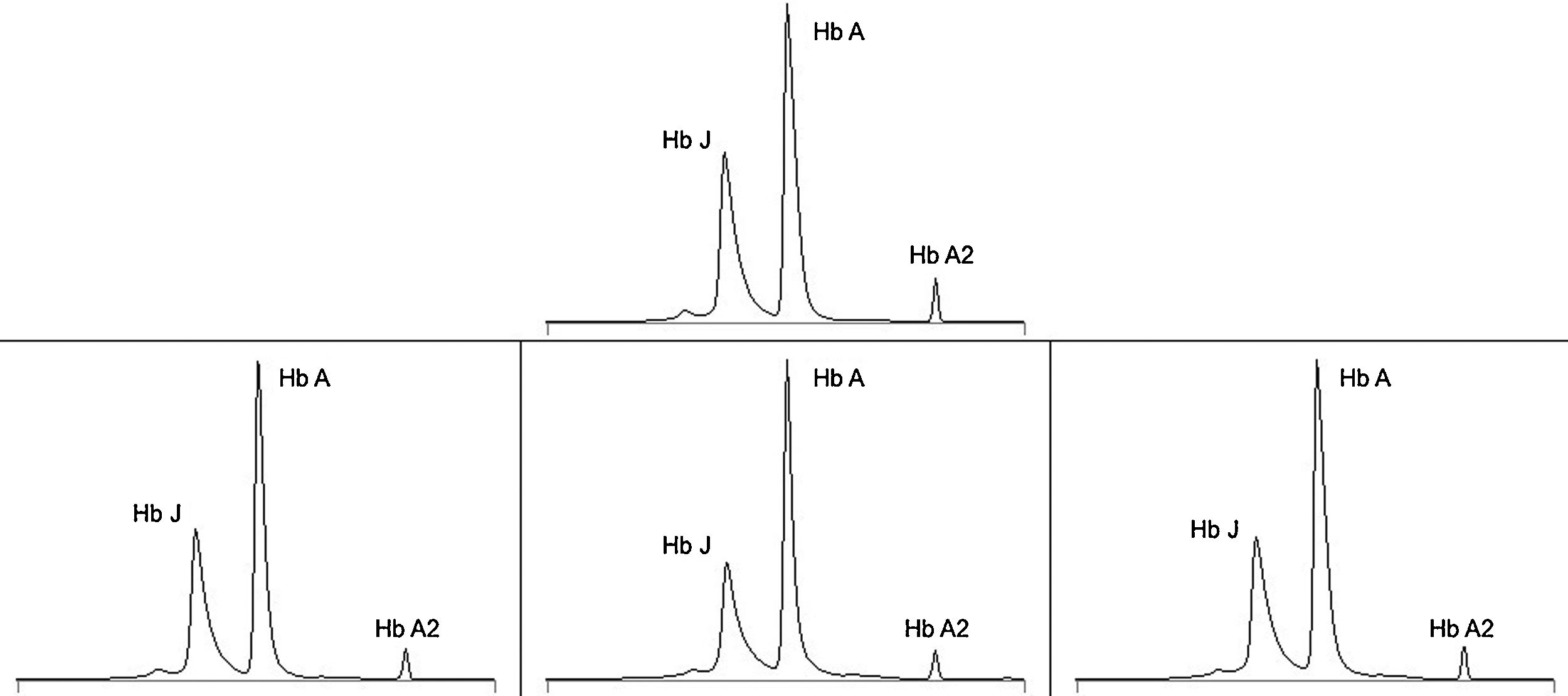

Haemoglobin electrophoresis was performed, detecting a haemoglobin variant interpreted as haemoglobin J (haemoglobin in zone 12: 39.2%) and only 52% haemoglobin A (Fig. 1).

Haemoglobin electrophoresis. Above, result for the first case in 2018, interpreted as haemoglobin J (Hb J). Below, results for the second case interpreted in 2015 as possible haemoglobin Shepherds Bush (left), in 2016 as possible haemoglobin Andrew-Minneapolis (centre) and in 2018 as possible haemoglobin Fannin-Lubbok (right). Under normal conditions, there is no haemoglobin J peak and more than 95% corresponds to haemoglobin A (Hb A). Haemoglobin A2 (Hb A2) was normal in all cases.

With these results, a gene sequencing study was ultimately conducted which identified the heterozygous mutation c.422C>A (p.Ala141Asp) in the human beta-globulin (HBB) gene, a pathological variant associated with the production of haemoglobin Himeji in clinical databases.

The second case is that of a 74-year-old woman, the mother of the above patient and a native of Portugal with a history of ischaemic heart disease (having had episodes of unstable angina in 2007 and 2015), hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus being treated with oral antidiabetic drugs as of its diagnosis in 2005 up to 2016, when it was replaced with basal insulin (glargine). While on basal insulin, the patient had frequent evening episodes of hypoglycaemia, none of them serious. Her regular treatment included omeprazole, bisoprolol, acetylsalicylic acid, amlodipine, valsartan, hydrochlorothiazide and rosuvastatin.

She was referred for diabetes management and also showed a discrepancy between her fasting glucose levels, which ranged from 120 to 160 mg/dl, and her HbA1c determinations from recent years, which persistently exceeded 11%. Furthermore, she showed abnormalities on haemoglobin electrophoresis that were interpreted on different occasions as possible haemoglobin Shepherds Bush, Andrew-Minneapolis or Fannin-Lubbok (Fig. 1). Her serial complete blood count showed no abnormalities of interest.

In light of these results, the discrepancy with the patient’s blood glucose test results and awareness of her son’s haemoglobinopathy, an automated genetic sequencing study was conducted in the patient and detected the same heterozygous mutation associated with the production of haemoglobin Himeji.

At present, there are more than 1300 known haemoglobin variants.6 Approximately 80% are asymptomatic; the remaining 20% are associated with diseases such as haemolytic anaemia, polycythaemia and methaemoglobin.3,4 Widespread determination of HbA1c levels has led to a gradual increase in recent years in identification of clinical silent haemoglobin variants.3,7

Depending on the method of detection used, the same haemoglobinopathy might cause HbA1c results to be unexpectedly high or low compared to blood glucose determinations.2,4 Although some of these abnormalities in measurement can be detected and it is possible to take steps to correct them,2,5 if an abnormality in haemoglobin affects its ability to be glycosylated or if factors affecting the rate of erythrocyte turnover are involved, the results will be inaccurate regardless of the detection method employed.2,3

“Haemoglobin J” refers to a group of abnormal haemoglobins that all have faster electrophoretic mobility than haemoglobin A. Haemoglobin Himeji was first reported in 1986 in a Japanese male with diabetes mellitus;8 later on, cases in two Japanese families, cases in two members of a Portuguese family and another isolated case also in Portugal were reported as well.7–10 It is a variant with a higher oxygen affinity, a certain molecular instability and an increase in glycosylation of the NH2 end of the β chain,5,9 which would account for the falsely elevated HbA1c results obtained in our cases.

In patients who are carriers of haemoglobin Himeji, blood glucose control can be estimated more accurately using commercial methods that measure glycosylated serum proteins (fructosamine or glycosylated serum albumin).2,3 However, these tests only reflect mean glucose over approximately the past two weeks, and none of them has been correlated with the risk of developing chronic complications of diabetes mellitus.1–3 In these patients, therefore, self-monitoring of blood glucose or using a continuous glucose monitoring system is more important in evaluating the effectiveness of the treatment of the disease.

As they do not show symptoms, most patients who are carriers of haemoglobin Himeji are not aware of it. It has been reported, however, that they could have higher rates of haemolysis and lower rates of erythrocyte survival. Hence, in situations of haematological stress, compensatory reticulocytosis might not be adequate and this would create a predisposition to developing anaemia more easily and of a more severe nature than under normal conditions.10

Please cite this article as: García Urruzola F, Ares Blanco J, Bernardo Gutiérrez Á, Álvarez Álvarez S, Menéndez Torre E. Hemoglobina Himeji como causa de interferencia en la medición de la hemoglobina glicosilada. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2021;68:671–672.