The incidence of type 1 diabetes mellitus (DM1) has increased in many regions of the world, with the exception of Central America and the Caribbean.1,2 There are also marked differences according to race and ethnicity in one and the same region.3

In middle- or low-income countries, this alarming growth in incidence may constitute a challenge in the face of limited healthcare resources, resulting in the impossibility of implementing confirmatory testing in many cases.4 These same countries have a poor record in terms of incidence and mortality, particularly in children under four years of age.5

The Diabetes Mondiale Project Group (DIAMOND) study, published in the year 2000, reported that in 1990 Bogotá (Colombia) had 3.8 (95% confidence interval [95%CI]: 2.88–4.93) new cases per year per 100,000 children under 15 years of age,2 this being the only report corresponding to Colombia. A significant gender difference was demonstrated, with an incidence of 4.9 in boys and 2.9 in girls. This difference was among the highest in the world.2

Epidemiological data and information regarding the disease burden are crucial for designing better public policies, and should be updated on a regular basis. In this disease, as in other chronic disorders, health behavior can cause many complications, which increase the associated costs.6 It is therefore necessary to generate policies aimed at supporting and educating the individual and the family from a multidisciplinary perspective, including nurses, physicians, psychologists, psychiatrists and nutritionists.7

Based on the above, we decided to conduct a study to update the incidence of DM1 in children under 15 years of age in the city of Bogotá (Colombia).

An retrospective, descriptive observational study was carried out to estimate the incidence of DM1 using the capture and recapture method8 in the population under 15 years of age in this city in order to identify cases diagnosed during the period from 1 January to 31 December 2008.

The operational definition of DM1 was that of the American Diabetes Association (ADA), namely a diagnosis before 15 years of age and with the start of insulin therapy in the first 6 months after the diagnosis.9

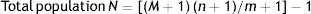

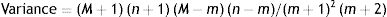

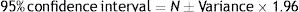

To this effect we identified the new cases from a primary source (M) and one or more secondary sources (n). Based on the duplicate cases (m), the total of the population of interest (N) and the 95%CI could be estimated, using the formula described below. The main assumption was that primary and secondary sources were independent. The formulas used were:

The primary sources were the office of pediatric endocrinologists in outpatient clinics, institutional outpatient clinics, and the Colombian Diabetes Association.

Secondary sources were the third-level emergency care departments of the Health Department of Bogotá and of private institutions where it was possible to consult the initial cases that may not have been seen by a pediatric endocrinologist in the following year (Hospital Universitario San Ignacio, Fundación Cardio-Infantil, Hospital de La Misericordia, Clínica Infantil Colsubsidio, Clínica de la Policía, Hospital Militar Central, Fundación Santa Fe de Bogotá and Hospital San Rafael).

Once the total number of patients was obtained, the incidence was estimated using as denominator the population of children under 15 years of age reported by the National Administrative Statistics Department (Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística [DANE]) for the year 2008.

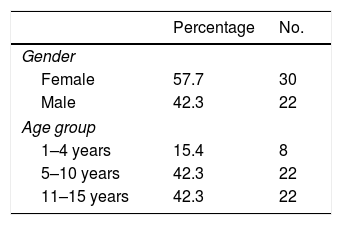

Twenty-eight cases were found in primary sources (M) and 33 in secondary sources (n). Nine of these patients were captured from both sources (m). A total of 52 patients were thus found. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of these patients.

General characteristics of the identified patients (n=52).

| Percentage | No. | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 57.7 | 30 |

| Male | 42.3 | 22 |

| Age group | ||

| 1–4 years | 15.4 | 8 |

| 5–10 years | 42.3 | 22 |

| 11–15 years | 42.3 | 22 |

| SD | Percentage | No. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Height categories for age | |||

| No data | 1.9 | 1 | |

| Short stature | <−2 | 19.2 | 10 |

| Risk of short stature | −2 to −1 | 9.6 | 5 |

| Normal | ≥−1 | 69.2 | 36 |

| BMI categories for age | |||

| No data | 1.9 | 1 | |

| Thinness | <−2 | 5.8 | 3 |

| Risk of thinness | ≥−2 to −1 | 13.5 | 7 |

| Adequate | ≥−1 to ≤1 | 61.5 | 32 |

| Overweight | >1 to ≤2 | 9.6 | 5 |

| Obesity | >2 | 7.7 | 4 |

SD: standard deviation; BMI: body mass index.

The capture and recapture method served to calculate a number of 98 (95%CI: 58–137). The level of ascertainment was 42.2%. The population under 15 years of age reported in 2008 for Bogotá was 1,844,022; the adjusted incidence of DM1 in Bogotá was therefore 5.3 (95%CI: 3.14–7.44) per 100,000 children under 15 years of age in the year 2008.

The incidence was almost 40% higher than that reported in the 1990 study using a similar methodology. However, the low level of ascertainment and the broad confidence intervals do not allow us to establish whether this difference is significant.

The detection of new cases of DM1 in Bogotá was seen to be limited, imprecise and with important under-recording.

Another limitation of this study is the inclusion of a population between 0–6 months in the denominator, which could result in underestimation of the incidence of DM1, since the population in this age range is not susceptible to DM1 according to the definition used.9 In our study, no cases below 12 months of age were recorded.

We sought to cover several secondary sources. In the year 2008, several centers lacked case history systematization to facilitate data collection. The registry of cases of DM1 in the emergency room is often omitted from the main diagnoses, since the disorder is not initially recognized.

Complete independence among sources cannot be guaranteed. In the event that the relationship among the sources proves positive, underestimation of the total number of patients – and therefore of the incidence – can be expected.

Taking into account the characteristics of the disease, it is particularly worrying that almost half of the patients in Bogotá were not captured from any source, despite the fact that there is good health coverage in the population. Although there were difficulties of access, the most likely sources were included.

We emphasize the importance of public policies that ensure the correct identification, recording and management of patients with DM1,10 and measurements of the epidemiological burden such as our study are important steps in this direction. We recommend a unified systematic registry that allows for the monitoring of changes in the incidence of DM1 and the improvement of public health policies.

FundingLaboratorios Novo Nordisk funded data compilation and organization through Ms. Jaddy Valero.

Thanks are due to Novo Nordisk for facilitating data compilation and organization through Ms. Jaddy Valero.

Castro T., Coll M., Duran P., Estrada J.M., Forero C., Lammoglia J.J., Lema A., Llano M., Ortiz T., Ospina J., Pinzón E., Roa S., Roselli A.I., Urueña M.V. and Valbuena F. Asociación Colombiana de Diabetes, Fundación Cardio-Infantil, Hospital Universitario San Rafael, Hospital Universitario Fundación Santa Fe, Hospital La Misericordia, Clínica Infantil Colsubsidio, Clínica de la Policía, Hospital Militar Central, Hospital el Tunal, Hospital Simón Bolivar and Hospital Occidente Kennedy.

The names of the members of the Diamebog Group are listed in Appendix A.

Please cite this article as: Cespedes C, Montaña-Jimenez LP, Lasalvia P, Aschner P, On behalf of Grupo Diamebog. Cambios en la incidencia de diabetes mellitus tipo 1 en menores de 15 años en la ciudad de Bogotá, Colombia. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2020;67:289–291.