Functioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (pNETs) account for 1% of all pancreatic neoplasms. Tumours of this kind that produce ACTH are even less frequent, representing 15% of the causes of ectopic ACTH secretion.1–3 They exhibit aggressive behavior and are mostly well differentiated (94%).1 When surgery is not possible, few effective therapeutic strategies are available against such tumours.4 Their management thus remains a challenge. We present our experience with a case of an initially non-functioning pNET that led to the development of Cushing's syndrome (CS) three years after the diagnosis, and a second case initially manifesting with evident CS.

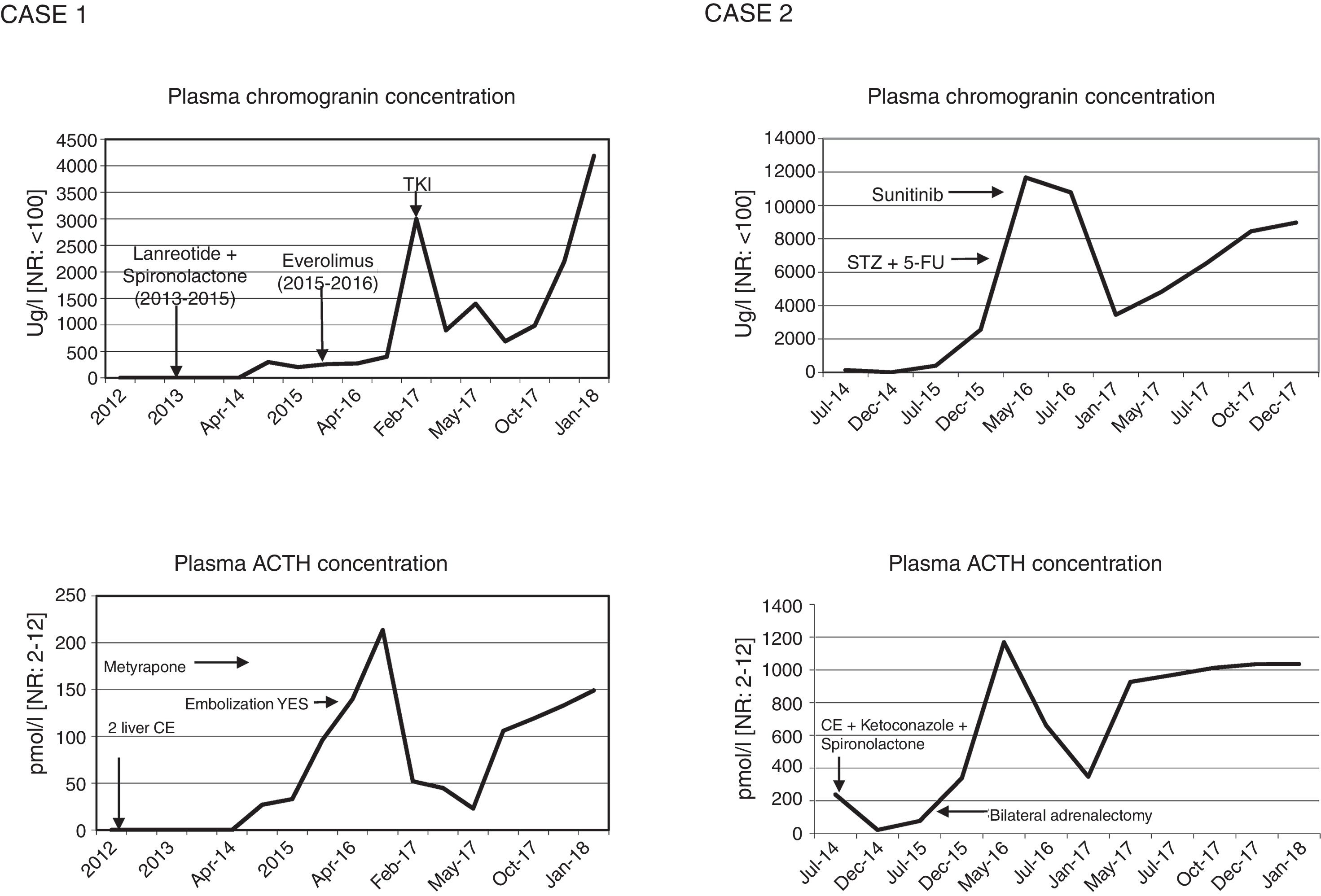

Case 1A 57-year-old male was diagnosed in 2011 with well-differentiated pNET measuring 2cm in size in the tail of the pancreas (pT2N0, grade 2 with Ki67 15%) and subjected to subtotal pancreatectomy and splenectomy, with no signs of CS. In December 2012, he suffered local recurrence and liver metastases. In June 2013, enucleation of the pancreatic head and liver radiofrequency ablation or alcoholization was performed, according to the type of lesion. However, due to hepatic progression of the disease, lanreotide was started in October 2013 (120mg/28days), together with spironolactone in view of a tendency toward hypertension (50mg/day). In October 2014, due to hepatic progression, lanreotide was replaced by everolimus 10mg/day, administered from February 2015 to March 2016, with a partial response. In parallel, in November 2014 the patient developed paraneoplastic CS with a worsening general condition, asthenia, myopathy, anasarca, diabetes mellitus, hypertensive crisis, bilateral pulmonary thromboembolism and severe hypokalemia (2.19.mmol/l) with metabolic alkalosis. The physical examination revealed facial flushing and hyperpigmentation. Plasma ACTH was 122pg/ml [normal range (NR): 10–60], with serum cortisol 29.5μg/dl [NR: 10–25] and urinary free cortisol (UFC) 143.8μg/day [NR: 20–100]. Computed tomography (CT) showed bilateral adrenal gland hyperplasia. In view of these findings, ketoconazole was started but subsequently replaced by metyrapone due to toxic hepatitis (2000–4000mg/day). Because of poor control of hypercortisolism, in September 2016 embolization was performed, but only of the left adrenal gland due to problems with vascular access to the right gland, with a subsequent persistence of high ACTH (970pg/ml) and plasma cortisol levels (63.3μg/dl). In addition, in April and July 2016 chemoembolization (CE) was indicated in two sessions due to metastatic liver progression. Radiologically, signs of liver disease progression continued and a metastatic lytic lesion appeared in L1. A tyrosine kinase inhibitor (lenvatinib) was started in February 2017, with a partial response. The CT study in January 2018 showed the tumour with no radiographic progression but with an elevated ACTH concentration of 676pg/ml, serum cortisol 25.6μg/dl and UFC 766.7μg/day, under treatment with lenvatinib and metyrapone.

Case 2A 50-year-old woman was diagnosed with CS in 2014 secondary to ectopic ACTH secretion due to a well-differentiated pNET (grade 2, with Ki67 15%), and non-resectable liver metastases. She suffered from postural instability, asthenia and proximal muscle weakness. The physical examination revealed abdominal bloating, hyperpigmentation, hirsutism, and acne. The laboratory tests revealed a plasma ACTH concentration of 1085pg/ml, serum cortisol 30μg/dl and UFC 3900μg/24h, with no evidence of slowing in low and high dose dexamethasone suppression testing. The CT scan revealed a solid tumour in the isthmus-head of the pancreas, with liver dissemination. Scintigraphy for somatostatin receptors proved positive in the head of the pancreas. Chemoembolization of the metastases was performed, a stent was placed in the portal vein, and ketoconazole and spironolactone were started for the control of CS. However, a plasma ACTH level of 758.34pg/ml persisted, with UFC 664μg/day, and bilateral adrenalectomy was indicated (June 2015). In view of the above, in January 2016 chemotherapy (streptozocin and 5-fluorouracil) was started, ending in April due to liver progression after three cycles. Sunitinib (37.5g/day) was started in May.

The CT scan in January 2018 showed no evidence of radiographic progression, but ACTH remained high (4700pg/ml), with UFC 132μg/day under replacement therapy with hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone.

DiscussionThe aim of treatment in non-resectable ACTH-secreting pNETs is biochemical control of CS and the prevention of disease progression.5 Serum chromogranin is the general biochemical marker for monitoring tumour progression. However, when the tumour is functional, the excess hormone is also a progression marker. Thus, in the rare cases of pNETs that produce ACTH, as in our patients, a parallel relationship is observed between the ACTH and chromogranin levels, depending on the functionality of the tumour (Fig. 1). Inadequate control of hypercortisolism is indicative of a poor prognosis.2,3,6 It is advisable to control this alteration before treatment is started. In tumours expressing SSTR-2 and SSTR-5, somatostatin analogs are a therapeutic strategy for stabilizing tumour growth and lowering hormone secretion.7 Another therapeutic option for hypercortisolemia is metyrapone or ketoconazole, as well as bilateral adrenalectomy, which has been shown to improve survival in the first two years,2 as in our second case. In the case of disease progression in non-resectable advanced cancer, everolimus and sunitinib,6,7 and even lenvatinib, are new and promising options, though there is little long-term experience with these drugs. Everolimus was used in the first case without success, while sunitinib in the second patient resulted in disease stabilization. Traditional chemotherapy with streptozocin and 5-fluorouracil is an option, but proved unsuccessful in the second case. Radionuclide therapy may be effective when SRS or 68Ga-DOTA-peptide-PET/CT are positive.2,3

Change in functionality due to tumour cell pluripotency makes management difficult. In the first initially non-functioning case, ACTH hyperfunction developed after three years, and repeat histological study of the metastatic foci proved helpful in defining the biological behavior of the tumour.5

It can be concluded that evidence-based treatment decisions are lacking for ACTH-secreting pNETs. In the described cases, treatment changes were made without a fully effective response. Randomized clinical trials are needed to establish the best treatment options, since short case series such as our own are currently the only source of scientific evidence.3,4

Conflicts of interestThe authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Simó-Servat A, Peiró I, Villabona C. Tumor neuroendocrino pancreático secretor de corticotropina, un reto en el manejo terapéutico. A propósito de 2 casos. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2019;66:204–206.