The tools for analyzing the case-mix in outpatient care are scarce and unsatisfactory. The objective of this work by the Sociedad Castellano Manchega de Endocrinología, Nutrición y Diabetes (SCAMEND) was the development of a tool that allows to analyze the the case-mix in outpatient care in Endocrinology and Nutrition considering the complexity of the patient disease.

Material and methodsThe SCAMEND index of complexity in outpatient care in Endocrinology and Nutrition (ISCCE-EyN) was defined using the Delphi method with two rounds between endocrinologists, comparing the complexity of each consult with that of a review visit of primary hypothyroidism.

ResultsThe first visits were considered more complex than the successive visits. Non-neoplastic thyroid pathology and uncomplicated overweight/obesity were considered the least complex diseases, while metabolopathies, multiple endocrine neoplasm syndromes and adrenal carcinoma were considered the most complex. The degree of consensus was high in most of the diseases analyzed.

ConclusionsWe present a tool that allows to analyze the case-mix in outpatient care in Endocrinology and Nutrition considering the inherent complexity of the disease of the patient attended. This tool can be used to make comparisons between centres, to better allocate resources within a given service or for self-evaluation.

Las herramientas para analizar la casuística en consultas externas son escasas e insatisfactorias. El objetivo de este trabajo de la Sociedad Castellano Manchega de Endocrinología, Nutrición y Diabetes (SCAMEND) fue el desarrollo de una herramienta que permita analizar la casuística de las consultas externas de Endocrinología y Nutrición teniendo en cuenta la complejidad de la patología atendida.

Material y métodosSe definió el Índice SCAMEND de Complejidad en Consultas Externas de Endocrinología y Nutrición (ISCCE-EyN) mediante método Delphi con dos rondas entre especialistas en Endocrinología y Nutrición, comparando la complejidad de cada patología con la de una revisión de hipotiroidismo primario.

ResultadosLas primeras visitas fueron consideradas más complejas que las visitas sucesivas. La patología tiroidea no neoplásica y el sobrepeso/obesidad sin complicaciones fueron consideradas las patologías menos complejas, mientras que las metabolopatías, los síndromes de neoplasias endocrinas múltiples y el carcinoma suprarrenal, fueron consideradas las más complejas. El grado de consenso fue elevado en la mayoría de las patologías analizadas.

ConclusionesPresentamos una herramienta que permite analizar la casuística de las consultas externas de Endocrinología y Nutrición teniendo en cuenta la complejidad inherente a la patología del paciente atendido. Esta herramienta puede servir para realizar comparaciones entre centros, para asignar mejores recursos dentro de un determinado servicio o para la autoevaluación.

Departments of Endocrinology and Nutrition perform care, teaching, management and research functions. Care activity is performed both in hospital (inpatients and day hospital patients) and in the outpatient area through endocrinology and nutrition outpatient clinics.1

From a management viewpoint, tools have been developed allowing for the analysis of hospital case mixes with respect to inpatients. Diagnosis-related groups (DRGs), as a classification system grouping patients according to their primary and secondary diagnoses, type of treatment, type of surgery performed, age or status at discharge, are widely used in this regard, each group being weighted to determine the cost to be expected from the admission involved (or the money the hospital receives for it).2

However, although attempts have been made since the last century to implement tools to analyze the case mixes of outpatient clinics,3,4 in most hospitals the analysis that managing boards continue to make of non-surgical outpatient case mixes is based solely on the number of visits, with only first and subsequent visits being distinguished, and no account being taken of either the diagnosis or the complexity of the disorder being treated.

The present study was designed to develop a tool to analyze the case mixes of endocrinology and nutrition outpatient clinics, taking into consideration not only whether a visit is a first or a subsequent visit, but also the complexity inherent to the disorder being treated. This tool was developed on the occasion of the research studies conducted prior to the 18th Congress of the Sociedad Castellano Manchega de Endocrinología, Nutrición y Diabetes (SCAMEND), and was referred to as the SCAMEND Index of Complexity in Endocrinology and Nutrition Outpatient Clinics (Índice SCAMEND de Complejidad en Consultas Externas de Endocrinología y Nutrición [ISCCE-EyN]).

Material and methodsDelphi methodology was used in two rounds for the development of the ISCCE-EyN.

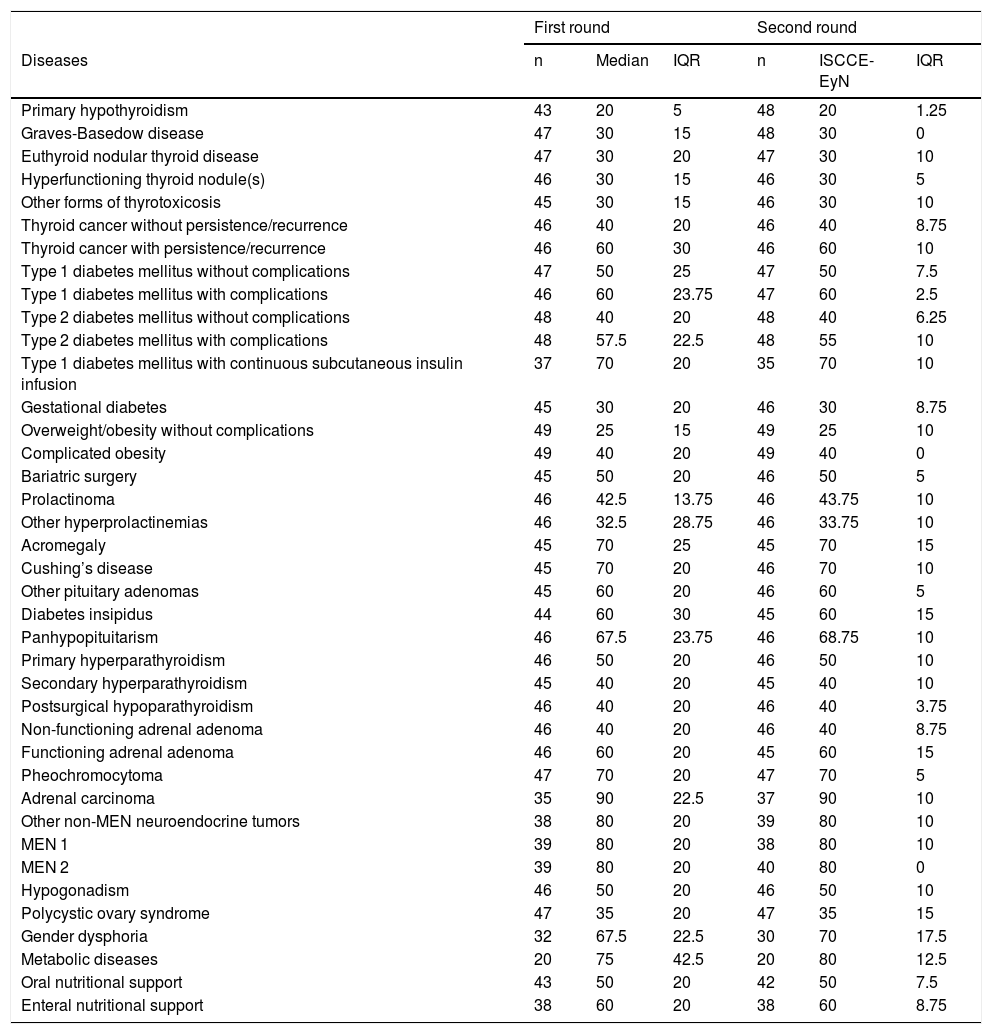

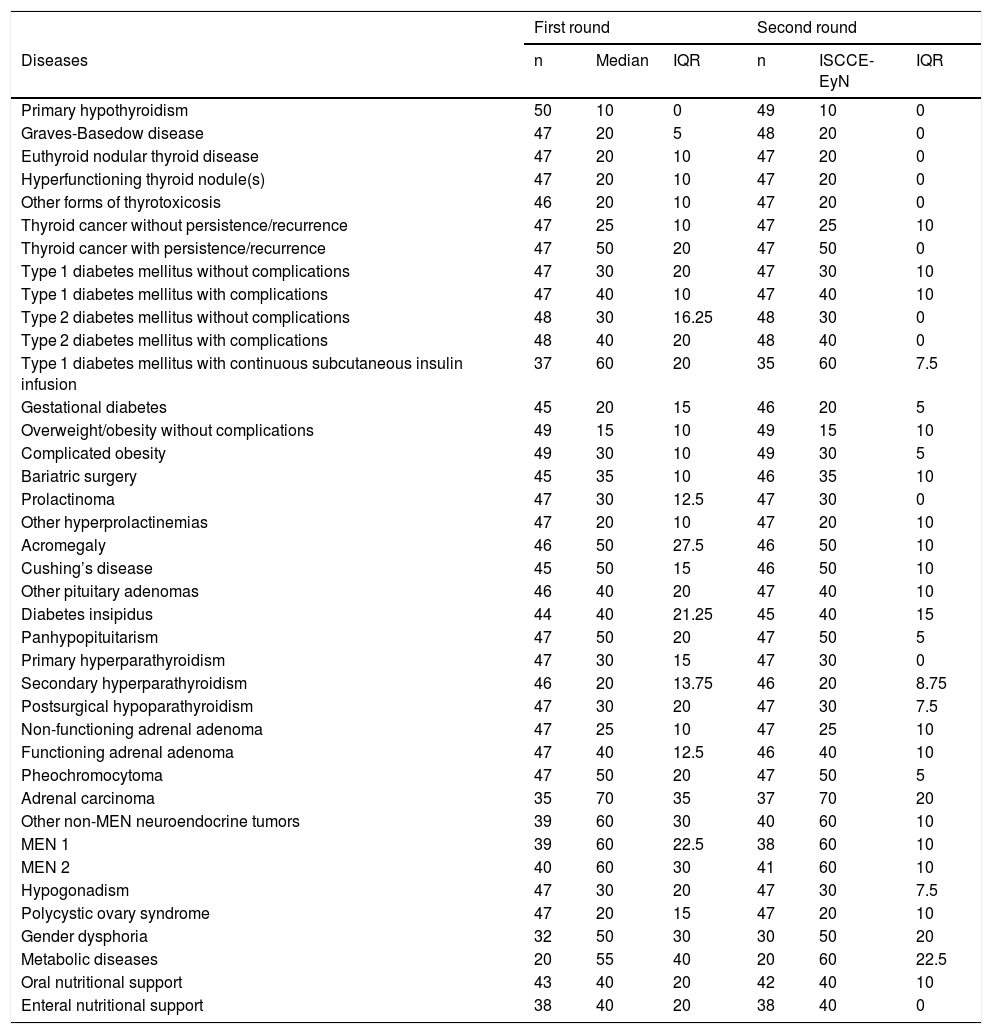

A list of diseases attended to in endocrinology and nutrition outpatient clinics was previously defined (Tables 1 and 2). Although the list is not exhaustive, it comprises the vast majority of disease conditions seen in an endocrinology and nutrition outpatient clinic in both specialized centers and first-level hospitals and in university hospital outpatient clinics.

Median scores of the different disease conditions at the first visits, interquartile range (IQR) of the scores assigned by the participants, and the number of participants (n) assigning scores to each of the diagnoses in the first and second rounds. The median of the second round constitutes the ISCCE-EyN score.

| First round | Second round | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diseases | n | Median | IQR | n | ISCCE-EyN | IQR |

| Primary hypothyroidism | 43 | 20 | 5 | 48 | 20 | 1.25 |

| Graves-Basedow disease | 47 | 30 | 15 | 48 | 30 | 0 |

| Euthyroid nodular thyroid disease | 47 | 30 | 20 | 47 | 30 | 10 |

| Hyperfunctioning thyroid nodule(s) | 46 | 30 | 15 | 46 | 30 | 5 |

| Other forms of thyrotoxicosis | 45 | 30 | 15 | 46 | 30 | 10 |

| Thyroid cancer without persistence/recurrence | 46 | 40 | 20 | 46 | 40 | 8.75 |

| Thyroid cancer with persistence/recurrence | 46 | 60 | 30 | 46 | 60 | 10 |

| Type 1 diabetes mellitus without complications | 47 | 50 | 25 | 47 | 50 | 7.5 |

| Type 1 diabetes mellitus with complications | 46 | 60 | 23.75 | 47 | 60 | 2.5 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus without complications | 48 | 40 | 20 | 48 | 40 | 6.25 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus with complications | 48 | 57.5 | 22.5 | 48 | 55 | 10 |

| Type 1 diabetes mellitus with continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion | 37 | 70 | 20 | 35 | 70 | 10 |

| Gestational diabetes | 45 | 30 | 20 | 46 | 30 | 8.75 |

| Overweight/obesity without complications | 49 | 25 | 15 | 49 | 25 | 10 |

| Complicated obesity | 49 | 40 | 20 | 49 | 40 | 0 |

| Bariatric surgery | 45 | 50 | 20 | 46 | 50 | 5 |

| Prolactinoma | 46 | 42.5 | 13.75 | 46 | 43.75 | 10 |

| Other hyperprolactinemias | 46 | 32.5 | 28.75 | 46 | 33.75 | 10 |

| Acromegaly | 45 | 70 | 25 | 45 | 70 | 15 |

| Cushing’s disease | 45 | 70 | 20 | 46 | 70 | 10 |

| Other pituitary adenomas | 45 | 60 | 20 | 46 | 60 | 5 |

| Diabetes insipidus | 44 | 60 | 30 | 45 | 60 | 15 |

| Panhypopituitarism | 46 | 67.5 | 23.75 | 46 | 68.75 | 10 |

| Primary hyperparathyroidism | 46 | 50 | 20 | 46 | 50 | 10 |

| Secondary hyperparathyroidism | 45 | 40 | 20 | 45 | 40 | 10 |

| Postsurgical hypoparathyroidism | 46 | 40 | 20 | 46 | 40 | 3.75 |

| Non-functioning adrenal adenoma | 46 | 40 | 20 | 46 | 40 | 8.75 |

| Functioning adrenal adenoma | 46 | 60 | 20 | 45 | 60 | 15 |

| Pheochromocytoma | 47 | 70 | 20 | 47 | 70 | 5 |

| Adrenal carcinoma | 35 | 90 | 22.5 | 37 | 90 | 10 |

| Other non-MEN neuroendocrine tumors | 38 | 80 | 20 | 39 | 80 | 10 |

| MEN 1 | 39 | 80 | 20 | 38 | 80 | 10 |

| MEN 2 | 39 | 80 | 20 | 40 | 80 | 0 |

| Hypogonadism | 46 | 50 | 20 | 46 | 50 | 10 |

| Polycystic ovary syndrome | 47 | 35 | 20 | 47 | 35 | 15 |

| Gender dysphoria | 32 | 67.5 | 22.5 | 30 | 70 | 17.5 |

| Metabolic diseases | 20 | 75 | 42.5 | 20 | 80 | 12.5 |

| Oral nutritional support | 43 | 50 | 20 | 42 | 50 | 7.5 |

| Enteral nutritional support | 38 | 60 | 20 | 38 | 60 | 8.75 |

Median scores of the different disease conditions at the successive visits, interquartile range (IQR) of the scores assigned by the participants, and the number of participants (n) assigning scores to each of the diagnoses in the first and second rounds. The median of the second round constitutes the ISCCE-EyN score.

| First round | Second round | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diseases | n | Median | IQR | n | ISCCE-EyN | IQR |

| Primary hypothyroidism | 50 | 10 | 0 | 49 | 10 | 0 |

| Graves-Basedow disease | 47 | 20 | 5 | 48 | 20 | 0 |

| Euthyroid nodular thyroid disease | 47 | 20 | 10 | 47 | 20 | 0 |

| Hyperfunctioning thyroid nodule(s) | 47 | 20 | 10 | 47 | 20 | 0 |

| Other forms of thyrotoxicosis | 46 | 20 | 10 | 47 | 20 | 0 |

| Thyroid cancer without persistence/recurrence | 47 | 25 | 10 | 47 | 25 | 10 |

| Thyroid cancer with persistence/recurrence | 47 | 50 | 20 | 47 | 50 | 0 |

| Type 1 diabetes mellitus without complications | 47 | 30 | 20 | 47 | 30 | 10 |

| Type 1 diabetes mellitus with complications | 47 | 40 | 10 | 47 | 40 | 10 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus without complications | 48 | 30 | 16.25 | 48 | 30 | 0 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus with complications | 48 | 40 | 20 | 48 | 40 | 0 |

| Type 1 diabetes mellitus with continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion | 37 | 60 | 20 | 35 | 60 | 7.5 |

| Gestational diabetes | 45 | 20 | 15 | 46 | 20 | 5 |

| Overweight/obesity without complications | 49 | 15 | 10 | 49 | 15 | 10 |

| Complicated obesity | 49 | 30 | 10 | 49 | 30 | 5 |

| Bariatric surgery | 45 | 35 | 10 | 46 | 35 | 10 |

| Prolactinoma | 47 | 30 | 12.5 | 47 | 30 | 0 |

| Other hyperprolactinemias | 47 | 20 | 10 | 47 | 20 | 10 |

| Acromegaly | 46 | 50 | 27.5 | 46 | 50 | 10 |

| Cushing’s disease | 45 | 50 | 15 | 46 | 50 | 10 |

| Other pituitary adenomas | 46 | 40 | 20 | 47 | 40 | 10 |

| Diabetes insipidus | 44 | 40 | 21.25 | 45 | 40 | 15 |

| Panhypopituitarism | 47 | 50 | 20 | 47 | 50 | 5 |

| Primary hyperparathyroidism | 47 | 30 | 15 | 47 | 30 | 0 |

| Secondary hyperparathyroidism | 46 | 20 | 13.75 | 46 | 20 | 8.75 |

| Postsurgical hypoparathyroidism | 47 | 30 | 20 | 47 | 30 | 7.5 |

| Non-functioning adrenal adenoma | 47 | 25 | 10 | 47 | 25 | 10 |

| Functioning adrenal adenoma | 47 | 40 | 12.5 | 46 | 40 | 10 |

| Pheochromocytoma | 47 | 50 | 20 | 47 | 50 | 5 |

| Adrenal carcinoma | 35 | 70 | 35 | 37 | 70 | 20 |

| Other non-MEN neuroendocrine tumors | 39 | 60 | 30 | 40 | 60 | 10 |

| MEN 1 | 39 | 60 | 22.5 | 38 | 60 | 10 |

| MEN 2 | 40 | 60 | 30 | 41 | 60 | 10 |

| Hypogonadism | 47 | 30 | 20 | 47 | 30 | 7.5 |

| Polycystic ovary syndrome | 47 | 20 | 15 | 47 | 20 | 10 |

| Gender dysphoria | 32 | 50 | 30 | 30 | 50 | 20 |

| Metabolic diseases | 20 | 55 | 40 | 20 | 60 | 22.5 |

| Oral nutritional support | 43 | 40 | 20 | 42 | 40 | 10 |

| Enteral nutritional support | 38 | 40 | 20 | 38 | 40 | 0 |

The ISCCE-EyN was defined with a range of 0-100, where a score of 0 corresponds to a disease or situation for which no specific medical knowledge or preparation is required, while a score of 100 indicates the most complex disease or situation which a specialist in Endocrinology and Nutrition could treat on an outpatient basis.

The concept of complexity has several dimensions and includes both the time needed to adequately care for the patient, considering his or her disease, and the intrinsic difficulty of the disease, as well as the need for training and study on the part of the physician, all these being elements of a markedly subjective nature. Complexity in our index does not include the need for actions outside the consulting room of the endocrinologist, such as for example nursing education activities or consultation with dieticians, psychologists or other medical specialties. However, it does include, for example, the prescription of diets or physical exercise, or strategies for behavioral change-motivation when such activities are performed by the endocrinologist in the consulting room.

On an arbitrary basis, an ISCCE-EyN 10 score was assigned to the follow-up visit of a patient with primary hypothyroidism subjected to replacement therapy. Accordingly, the complexity of all other diagnoses (on either the first or successive visits) was compared with a primary hypothyroidism follow-up visit. In other words, a disorder with an ISCCE-EyN 30 score would require three times as much time in the consulting room, or would involve three times as much difficulty, or would require three times as much training or study as a primary hypothyroidism follow-up visit, or a combination of all the above. An analogy can be established between complexity and its three dimensions (duration of consultation, intellectual difficulty and need for training) and the volume of a geometric figure and its three dimensions in space. In effect, in the same way that a figure that is 30% longer, 50% wider and 50% taller than another figure has approximately three times the volume of the latter (1.3 ⋅ 1.5 ⋅ 1.5 ≈ 3), consultation regarding a disease condition requiring 30% more time and also 50% more intellectual effort in consultation, together with 50% more training than a primary hypothyroidism follow-up visit, would be three times more complex than the latter.

The participating endocrinologists were all specialists in Endocrinology and Nutrition who had completed their training period and were members of the SCAMEND and/or endocrinologists of the Servicio de Salud de Castilla-La Mancha (SESCAM). They were asked to fill out a spreadsheet assigning complexity scores to each of the predefined diagnoses, whether seen on the first or subsequent visits. There were no open questions on the spreadsheet, though comments could be made. The participants were instructed that if their experience with any concrete diagnosis was very limited, thereby preventing them from having sufficient criteria for establishing a score, they should abstain from scoring that diagnosis. When issuing their assessment, the participants were unaware of the score assigned or going to be assigned by the other participants to each of the disease conditions. At no time were these scores available to the other participants (except to the principal investigator, who issued his/her scores before receiving those of the other participants). Of course, for one given diagnosis, the case mixes or possible nuances are almost infinite; the participants were therefore asked to think of an average patient for each of the disease conditions.

Once all the participants had issued their scores, the median score was calculated for each diagnosis, and another spreadsheet was sent to each participant including both the score he or she had assigned in the first round to each diagnosis and the median score assigned by the group to each diagnosis. The participants were asked to score the diagnoses again, encouraging them to seek consensus within the group but leaving them free to score as they considered most appropriate. The instructions to participants, which were delivered together with each spreadsheet, as well as an example of a second round worksheet sent with the first round scores of a participant (the first round spreadsheet did not contain columns B to E of the second round), are included in the Supplementary material.

With the scores assigned in the second round, the median score corresponding to each diagnosis was calculated again, defining the ISCCE-EyN of the diagnosis.

To determine the degree of consensus for each diagnosis, the interquartile range (IQR) of the score assigned to each disease condition was calculated, and consensus was defined as maximum for IQR < 1.5, great for ≤ 10, moderate for > 10 but ≤ 20, and poor for >20.

In addition, an analysis was made to determine whether the mean scores assigned by each participant were correlated to the number of years elapsed from the end of his or her resident in training period. The Spearman correlation index was calculated to this effect. Likewise, we examined whether the type of hospital in which each participant carried out his or her professional practice influenced the mean scores assigned by dividing the hospitals into three groups: those attending less than 5000, between 5000–15,000, or more than 15,000 patients in the year 2018 in the Endocrinology and Nutrition outpatient clinic. The chi-square test was used to analyze the relationship between the mean score assigned by each participant and the type of hospital where he or she was working. The Spearman correlation index was also used to determine whether there was a relationship between the number of participants who assigned scores to each diagnosis and the degree of consensus reached for each diagnosis.

ResultsThe first round involved 50 specialists in Endocrinology and Nutrition, 48 of whom worked in public hospitals in Castilla-La Mancha and two in public hospitals in the Community of Madrid. The time elapsed from their completion of specialized training was 14 ± 9 years (mean ± standard deviation [SD]), and 56% were women. Thirty-four percent of the participants worked in Departments or Units that had seen more than 15,000 patients in 2018, 54% in Departments or Units that had seen between 5000–15,000 patients, and 12% in Units that had seen less than 5000 patients in that year. Forty-nine endocrinologists participated in the second round. The only comments of some participants in the first round sheets were to indicate that their scores in nodular thyroid disease and thyroid cancer referred to a center in which neither ultrasound nor fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) were performed.

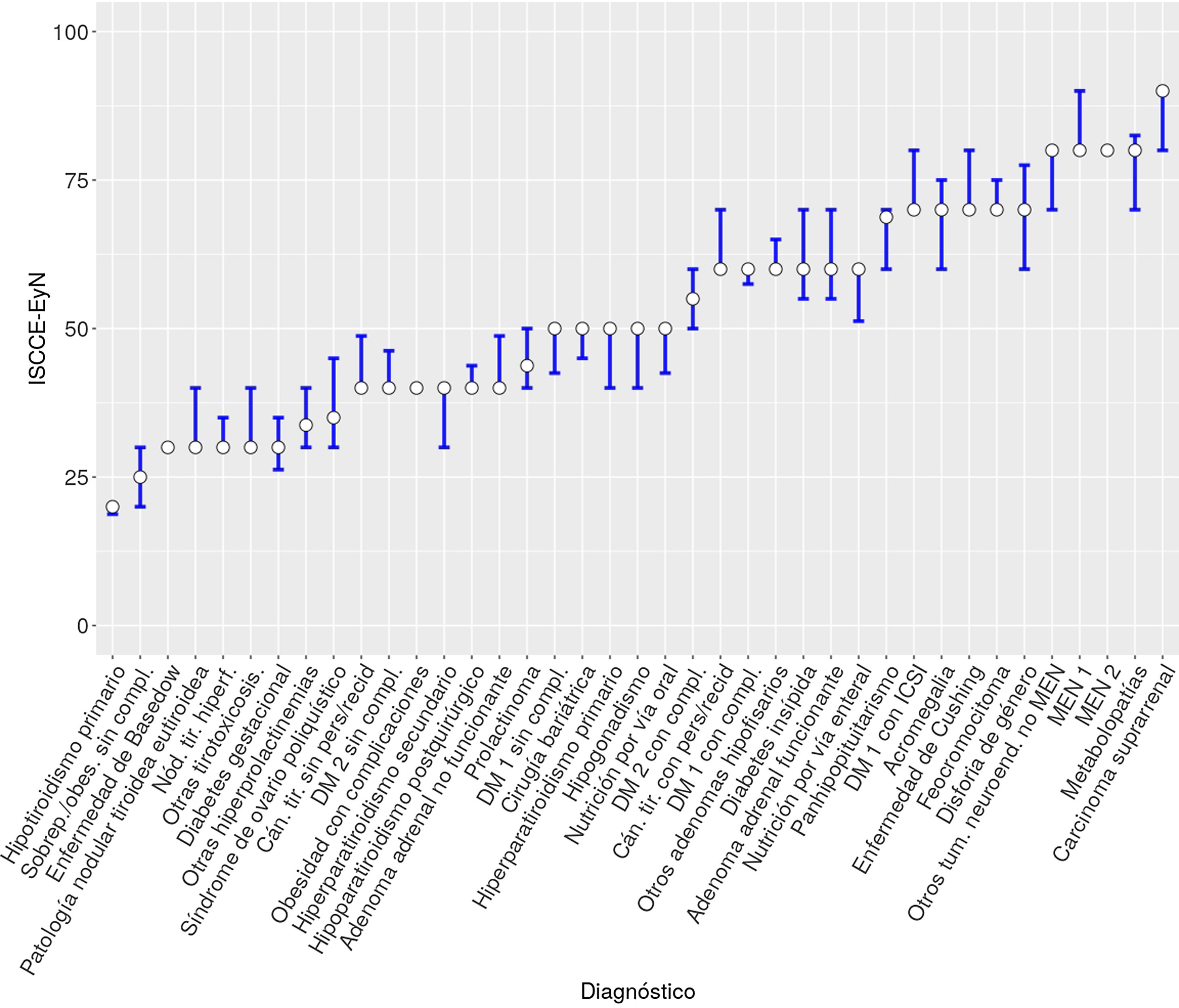

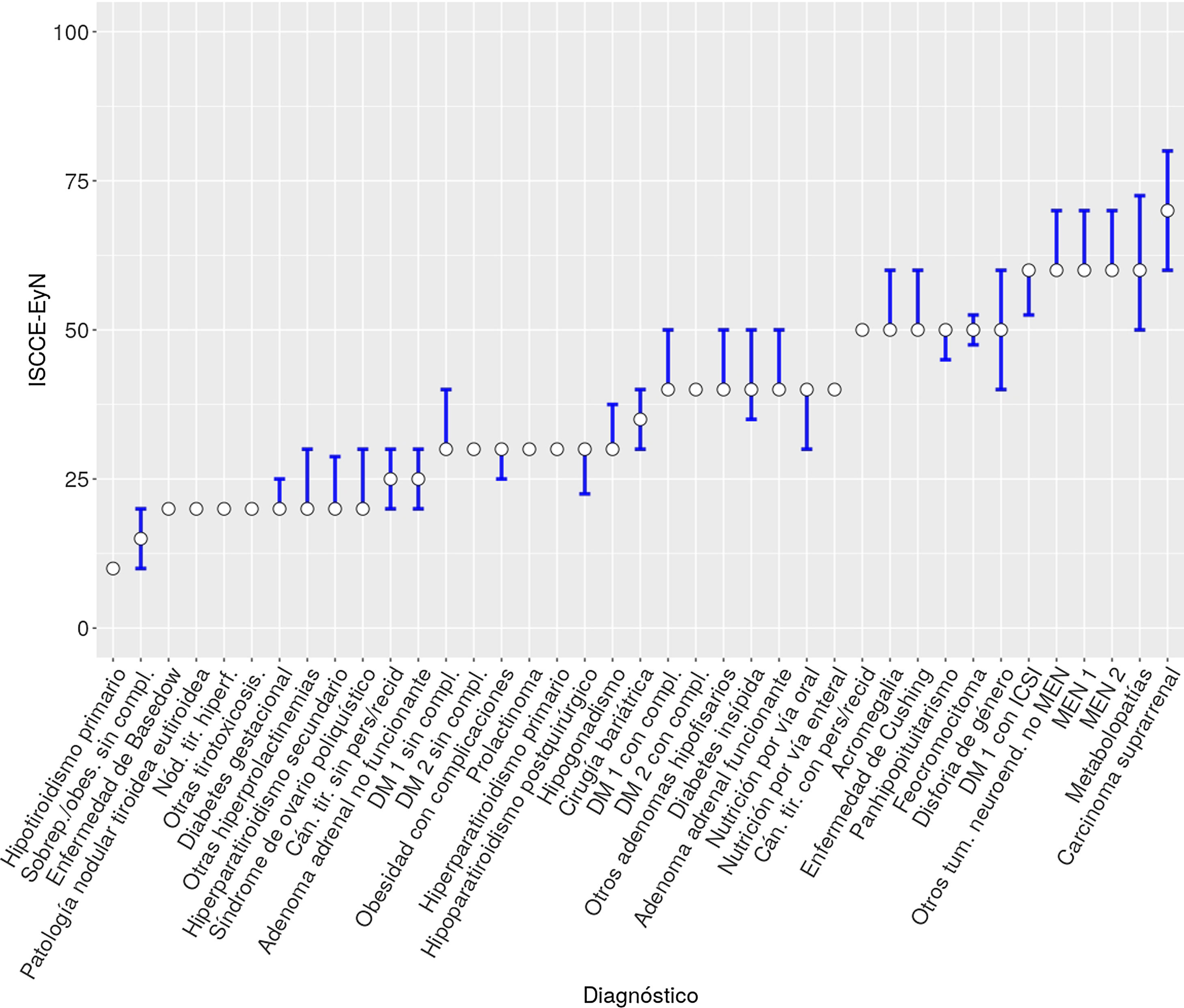

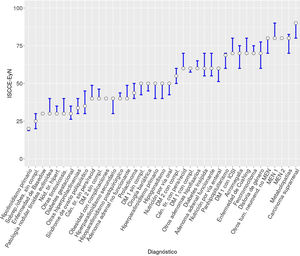

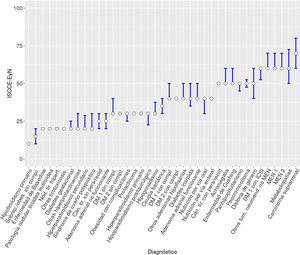

For all diagnoses, the first visits were considered to be more complex than the subsequent visits. Thyroid function disease and overweight/obesity without complications were considered to be the least complex conditions, while metabolic diseases, multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome, and adrenal carcinoma were considered to be the most complex. Table 1 and Fig. 1 show the ISCCE-EyN scores assigned to each disease for first visits. Table 2 and Fig. 2 show the ISCCE-EyN scores assigned to each disease for successive visits.

ISCCE-EyN scores assigned to first visits. The bars represent the interquartile range (IQR).

Cán. tir. sin pers/recid: thyroid cancer without persistence/recurrence; Cán. tir. con pers/recid: thyroid cancer with persistence/recurrence; DM 1 sin compl.: type 1 diabetes mellitus without complications; DM 1 con compl.: type 1 diabetes mellitus with complications; DM 1 con ICSI: type 1 diabetes mellitus with continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion; DM 2 sin compl.: type 2 diabetes mellitus without complications; DM 2 con compl.: type 2 diabetes mellitus with complications; MEN 1: multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 1; MEN 2: multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2; Nód. tir. hiperf.: hyperfunctioning thyroid nodule(s); Otros tum. neuroend. no MEN: other non-MEN neuroendocrine tumors; Sobrep./obes. sin compl.: overweight/obesity without complications.

ISCCE-EyN scores assigned to successive visits. The bars represent the interquartile range (IQR).

Cán. tir. sin pers/recid: thyroid cancer without persistence/recurrence; Cán. tir. con pers/recid: thyroid cancer with persistence/recurrence; DM 1 sin compl.: type 1 diabetes mellitus without complications; DM 1 con compl.: type 1 diabetes mellitus with complications; DM 1 con ICSI: type 1 diabetes mellitus with continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion; DM 2 sin compl.: type 2 diabetes mellitus without complications; DM 2 con compl.: type 2 diabetes mellitus with complications; MEN 1: multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 1; MEN 2: multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2; Nód. tir. hiperf.: hyperfunctioning thyroid nodule(s); Otros tum. neuroend. no MEN: other non-MEN neuroendocrine tumors; Sobrep./obes. sin compl.: overweight/obesity without complications.

As regards the degree of consensus reached, it was generally higher for successive visits than for first visits. At the first visits, the degree of consensus (Table 1) was total in 7.7% of the disorders (Graves-Basedow disease, obesity with complications and MEN 2), moderate in 15% (metabolic disease, acromegaly, diabetes insipidus, functioning adrenal adenoma, polycystic ovary syndrome and gender dysphoria), and considerable in the remaining 77.3% of the disorders. With regard to the successive visits (Table 2), consensus was total in 23.7% of the disorders (thyroid disease, except thyroid cancer with no evidence of recurrence or persistence, type 2 diabetes mellitus, prolactinoma, primary hyperparathyroidism and enteral nutritional support), moderate in 2.6% (diabetes insipidus), poor in 7.9% (adrenal carcinoma, gender dysphoria and metabolic disorders), and considerable in the remaining 65.8% of the disorders. A negative correlation was observed between the number of participants who scored each item and the interquartile range of the scores of the item for both first visits (rho = −0.44, p = 0.005613) and subsequent visits (rho = −0.55, p = 0.000232). In other words, the degree of consensus was greater in those diagnoses where more participants had sufficient experience to assign a score.

Tables 1 and 2 also show the median and interquartile ranges of the scores assigned in the first round. There were hardly any changes in the median values between the first and second rounds, while a decrease in interquartile range was recorded in all diseases for first visits and in the vast majority of diseases for subsequent visits (with the exceptions of thyroid cancer without persistence or recurrence, type 1 diabetes with complications, overweight/obesity without complications, follow-up of bariatric surgery, other forms of hyperprolactinemia, and non-functioning adrenal adenoma, in which there were no changes in the interquartile range). Thus, in the first round and for first visits, consensus was total, considerable, moderate, and poor in 0%, 2.6%, 69.2% and 28.2% of the disease conditions, respectively, versus in 0%, 28.9%, 50% and 21.1%, respectively, for successive visits.

No correlation was found between the experience of each participant (years elapsed from the end of specialized training) and the mean assigned scores, and no relationship was found between the mean scores and the type of hospital in which the participant worked.

DiscussionSpecialists in Endocrinology and Nutrition carry out most of their professional activity in outpatient clinics, attending to a broad variety of diseases. Unlike on the hospital ward, where indices assigning different weights to different diagnoses have been developed based on the clinical characteristics and costs involved, in outpatient clinics and from the management perspective, the main distinction made is between first and subsequent visits.

In addition, from the management board viewpoint, a ratio as small as possible between successive and first visits is rated positively. A recent study conducted by our group showed that more than half of the first patient visits to endocrinology and nutrition outpatient clinics corresponded to principal diagnoses of obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus and primary hypothyroidism. In many cases these conditions can be managed by primary care. However, thyroid cancer and type 1 diabetes mellitus were barely represented among the first visits and had a high successive:first visit ratio.5 All this leads to the paradoxical fact that, from the management perspective, it is more positively rated for endocrinologists to see patients with less complex disease as first visits than for endocrinologists to review complex cases not suitable for primary care.

In this regard, the ISCCE-EyN aims to serve as a tool for positively rating the work of endocrinologists when dealing with patients with complex diseases, allowing self-assessment and comparison between centers. Despite their interest, no tools have been found in the medical literature to assess the complexity of care in outpatient clinics, either in Endocrinology and Nutrition or in other medical specialties.

The high degree of consensus found in relation to most items, and the fact that the ISCCE-EyN has been developed in the context of a group of endocrinologists with varying degrees of experience working in centers ranging from district hospitals to university hospitals, supports the significance of the results obtained. Indeed, the fact that there were no differences in the scoring of the different diagnoses according to either the professional experience of the participants or the type of hospital involved, favors the consistency of the results. We believe that the fact that the degree of consensus was higher in items for which more participants were able to assign a score also favors the validity of our method.

There were practically no differences in the median scores between the first and second rounds, though the degree of consensus did increase markedly. We therefore believe that it would not have been practical to perform a third round, which might only have narrowed the interquartile ranges somewhat more without modifying the ISCCE-EyN.

The RECALSEEN study demonstrated the existence of differences in Endocrinology and Nutrition activity between different Spanish regional health systems6; the ISCCE-EyN may therefore afford only a partial view, since it was based on the assessments of SCAMEND members. Indices obtained with similar methodology among endocrinologists from other Spanish Autonomous Communities, or a study among specialists from the global National Health System - which could be promoted by the Spanish Society of Endocrinology and Nutrition (Sociedad Española de Endocrinología y Nutrición) – would overcome this possible partialness and could confirm our results. Likewise, they could be applied in other public and private healthcare systems as a tool for analyzing the case mix of endocrinology and nutrition outpatient clinics.

A weakness of our study is that it does not include certain disorders seen in endocrinology and nutrition outpatient clinics, such as eating disorders or nutritional support with home parenteral nutrition, and does not contemplate techniques recently incorporated to our services portfolio, such as thyroid ultrasound or FNAB of thyroid nodules. This is because most of our centers have endocrinologists who are fully dedicated to these concrete disorders or who perform these techniques, and so the other professionals have fewer criteria for assigning scores to them. Other conditions, such as dyslipidemia, are mainly seen in our clinics in the context of diabetes mellitus and obesity, or osteoporosis in the context of hyperparathyroidism, and their complexity has been included under these disorders. In this regard, such conditions are uncommon in our clinics as isolated diagnoses, except in some monographic centers.5 In other settings, however, conditions that are uncommon for us may have a greater impact in terms of patient care.

Another weakness of our index is that it only considers consulting room care by specialists in Endocrinology and Nutrition, when in fact the management of several of the conditions we treat is carried out on a multidisciplinary basis with the participation of nursing professionals or dieticians, among others. Nevertheless, although the quality of care received by the patients is conditioned by the work of all members of the multidisciplinary team, it is necessary to analyze and evaluate not only the work of the team as a whole but also that of each of its components, including the endocrinologist. Moreover, the treatment of other conditions, such as thyroid or neuroendocrine disorders, is almost exclusively managed by the endocrinologist.

Since we have defined the complexity of care in outpatient clinics taking into account not only the time required to provide quality care for each disease, but also the intrinsic difficulty involved - which includes the need for more or less training by the physician – the scores assigned to each disease are inevitably subjective. In this regard, preconceived ideas and a tendency to score rare, new and technical situations as being more complex may have exerted an influence. In this context, the greater complexity assigned to type 1 diabetes mellitus treated with continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion may be related to the need for the specific training of endocrinologists in technologies applicable to diabetes and/or longer consultation times. On the other hand, the lesser complexity scores assigned to obesity and type 2 diabetes without complications versus less prevalent conditions may be due in part to lesser experience with the latter, or to low perceived physician responsibility in relation to the prescription of diets and physical exercise, and the use of behavioral change strategies, which are usually implemented by other healthcare professionals. In any case, beyond these difficulties, the Delphi method employed facilitates the quantification of qualitative opinions and the promotion of consensus among different points of view.

It may seem that 50 participants are few. However, considering that the study was conducted among active SCAMEND members who had completed their specialized training period, together with other SESCAM endocrinologists even though not members (but in no case residents in training), the participants represented over 80% of the target population. This figure is analogous to those of other studies based on Delphi methodology, such as the ConT-SEEN project, conducted among endocrinologists dedicated to clinical nutrition throughout Spain.7

The ISCCE-EyN does not explicitly take into account the costs of care in outpatient clinics. This is in contrast to the DRGs2 in inpatient care, since the time assigned to each visit in the outpatient clinic is usually fixed: so many minutes for a first visit, so many for a subsequent visit, with the exception of some monographic centers, in which more time may be assigned. However, even in this context, the ISCCE-EyN implicitly takes into account costs: despite the fixed consultation times, the “surplus” minutes in the care of less complex disease conditions are used to care for more complex patients. It should be borne in mind that the care of more complex disorders requires more training, and that this has a cost. In this regard, in more complex diseases, due to their low prevalence or the need for specific technical training, monographic consultations could be useful and facilitate the optimization of both consultation time and the training received by the endocrinologist, as well as improve the outcomes.8

In sum, we offer a methodology and tool allowing us to analyze the case mix of endocrinology and nutrition outpatient clinics, taking into account the complexity inherent to the disease condition involved. This tool may be used to establish comparisons between centers, to assign better resources within a given department, or for self-assessment purposes. However, it is advisable to have our results confirmed in other Spanish Autonomous Communities, or better still from the perspective of the Spanish National Health System as a whole, and to perhaps consider additional aspects prior to applying them as a tool for resource allocation and benchmarking.

Conflicts of interestNone of the authors have conflicts of interest in relation to this article.

Albacete: Francisco Botella Romero, Silvia Aznar Rodríguez, Lourdes García Blasco, Cristina Lamas Oliveira, Luz María López Jiménez, José Juan Lozano García, Pedro José Pinés Corrales

Alcázar de San Juan-Tomelloso: Francisco Javier Gómez Alfonso, Julia Silva Fernández, Amparo Lomas Meneses, María López Iglesias, Florentino del Val Zaballos

Ciudad Real: Miguel Aguirre Sánchez-Covisa, Belén Fernández de Bobadilla, Álvaro García Manzanares Vázquez de Agredos, Carlos Roa Llamazares, Pedro Rozas Moreno

Cuenca: Mubarak Alramadan Aljamalah, David Martín Iglesias, Javier González López

Guadalajara: Visitación Álvarez de Frutos, Marta Cano Mejías, Enrique Costilla Martín, Sandra Herranz Antolín

Talavera de la Reina: Benito Blanco Samper, Petra de Diego Poza, Iván Quiroga López, Miguel Ángel Valero González

Toledo: Bárbara Cánovas Gaillemin, Enrique Castro Martínez, Inés Luque Fernández, Amparo Marco Martínez, Julia Sastre Marcos, Almudena Vicente Delgado

Villarrobledo: María Olmos Alemán, Rosa Pilar Quílez Toboso

Hospitals of the Community of Madrid: Elena Carrillo Lozano, Isabel Huguet Moreno.

Please cite this article as: Alfaro Martínez J-J, Peña-Cortés V-M, Gómez-García I-R, Moreno-Fernandez J, Platero-Rodrigo E, Martínez-García A, et al. Desarrollo de un índice de complejidad en consultas externas de Endocrinología y Nutrición. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2020;67:500–508.