Eating disorders are a group of conditions which have a huge impact on the health and performance of athletes. The aetiology of eating disorders is multifactorial, being influenced by genetic and environmental factors, but also involving psychological factors and factors specific to the practising of sport. Eating disorders are highly prevalent in sport, particularly in disciplines involving endurance, those that have weight-categories or those where low weight is a competitive advantage and aesthetics are important. Athletes with eating disorders need to be assessed and receive early, comprehensive treatment. Close monitoring of nutritional status is vital, especially with female athletes. Prevention is crucial and plays an invaluable role in this type of disorder, but represents a significant challenge for all professionals who look after athletes. Priority needs to be given to implementing structured nutrition training programmes for the athlete and their entourage to help prevent eating disorders.

Los Trastornos de Conducta Alimentaria (TCA) son un conjunto de enfermedades con gran impacto sobre la salud y el rendimiento de los deportistas. Estas enfermedades tienen una etiología multifactorial con influencia de factores genéticos y ambientales y donde también están implicados factores psicológicos y factores específicos de la práctica deportiva. Son patologías que tienen una gran prevalencia en el entorno deportivo, principalmente en deportes de resistencia, aquellos que establecen un control de peso por categorías o en aquellos deportes donde el bajo peso supone una ventaja competitiva y la estética es importante. Los deportistas con TCA deberían de ser evaluados y recibir un tratamiento integral precoz. Es indispensable el seguimiento estrecho del estado nutricional sobre todo en el caso de las deportistas femeninas. La prevención cobra un papel esencial e insustituible en estas patologías y constituye un auténtico desafío para todos los profesionales que atienden al deportista. Establecer programas estructurados de formación nutricional para el deportista y su entorno sería una prioridad para prevenir estas patologías.

Playing sport offers endless benefits, not just physical ones (mainly metabolic and cardiovascular) but also psychological and social ones. However, at the same time, the practice of sport entails problems. Athletes in general and, especially female athletes, can develop eating disorders (ED) that, once manifested, affect the well-being, health and performance of the athlete.

EDs are characterised by a persistent alteration related to eating that negatively impacts the health and psychosocial capacities of those who suffer from them.1 These pathologies are characterised by an excessive preoccupation with food, body weight and figure. Diagnosis is made with well-defined criteria2 typified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) or in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10).3 Included within these psychiatric pathologies are anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), binge eating disorders and other less prevalent entities. Their incidence is more common in women (90%) although they can also occur in men.4

These diseases, which were initially described by Richard Morton5 in the 17th-18th century (first medical approach to the disorder) and later by William Withey Gull (English doctor who coined the term anorexia nervosa) are still very present in our society where physical appearance is a symbol of success. While the prevalence of these disorders in the general population is around 1% for AN, 3–5% for BN and 13% for all eating disorders globally,1 in the sports world, these figures skyrocket. This has led to a significant increase in scientific publications on EDs in sports practice in the last two decades.

The objective of this work has been to review the current status of EDs in athletes and update a comprehensive approach to them.

Current situationEating disorders are a serious alteration that affects the morbidity, quality of life and mortality of those who suffer from them, constituting a true public health problem. EDs are known to be a major cause of mortality6 mainly due to cardiac causes7 and suicide.8

However, when these occur alongside the practice of sports, they are considered a major problem, not only because of the greater prevalence in this area compared to the general population, especially in certain disciplines, but also due to the consequences for the athlete's health and performance.9

a) MagnitudeWe do not have exact epidemiological data on the real prevalence of these pathologies in athletes because, on many occasions, the individuals themselves try to hide them. This means that the figures used are probably underestimating the true magnitude of the problem.

The prevalence data may vary according to the countries where the studies are carried out or the disciplines looked at, but all reflect a higher prevalence than in the general population.10 Globally, the prevalence of disorders and eating disorders varies between 0% and 19% in male athletes and 6% and 45% in female athletes.11 In a study of elite Norwegian athletes, about 42% of women participating in activities where body aesthetics are important and 24% of endurance athletes demonstrate symptoms of an eating disorder.10 In a North American trial carried out in adolescent athletes, the prevalence of these pathologies was 35.4%12 In another Norwegian study carried out in the same population group, a higher incidence of eating disorders (7%) was confirmed compared to a control group (2.3%).13

Consistent with these data on the prevalence of EDs in sports worldwide, in Spain their prevalence also reflects higher figures with respect to the general population. The Federación Española de Medicina del Deporte [Spanish Federation of Sports Medicine] estimates figures at around 4.2% and 39.2%.14

b) SignificanceThe significance of eating disorders has to do with the medical complications associated with this pathology. These are directly related to the severity of weight loss and the duration of the EDs.

Medical complications can affect virtually all organs and systems. Those that stand out include i) orofacial, such as halitosis or loss of teeth, ii) digestive: such as oesophagitis, delayed gastric emptying and constipation, iii) metabolic such as hypoglycaemia, hyperuricaemia, hypercholesterolaemia or hydroelectrolytic alterations, iv) endocrinological alterations such as hypogonadism, amenorrhoea and osteoporosis, v) haematological such as anaemia or pancytopaenia and altered immunity, vi) muscular such as weakness and muscle cramps or vii) cardiovascular such as orthostatic hypotension, palpitations or arrhythmias, among others. Table 1 lists the clinical signs and symptoms that an athlete with eating disorders may present with in more detail.

Signs, symptoms and laboratory test alterations of sports patients with ED.

| Symptoms | Signs | Laboratory test alterations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| General symptoms | Weight loss | Hypothermia | |

| Asthaenia, fatigue | Intolerance to the cold | ||

| Difficulty gaining expected weight in growing adolescents | |||

| Orofacial/dental | Halitosis | Dental erosion, cavities or loss of teeth | Salivary hyperamylasemia |

| Oral bleeding | Sensitive gums | ||

| Odynophagia | Enlargement of the parotid gland | ||

| Gastrointestinal | Dysphagia/odynophagia | Haematemesis | Altered liver enzyme profile |

| Retrosternal burning | Haemorrhoids | ||

| GER. Oesophagitis | Rectal fissure | ||

| Alteration in oesophageal and gastric motility, and delayed intestinal transit Constipation/diarrhoea | Rectal prolapse | ||

| Metabolic | Dizziness, lack of strength | Glucose metabolism disorders (hypoglycaemia) hyperuricaemia, hypercholesterolaemia | |

| Micronutrient deficiency | |||

| Endocrinological | Amenorrhoea and menstrual disturbances | Hypogonadism | Testosterone deficiency |

| Vaginal dryness | Hypoestrogenism | ||

| Dyspareunia | |||

| Decreased libido | Decrease LH, FSH | ||

| Infertility | T3 decrease and reverse T3 increase | ||

| POS (in BN) | Cortisol and GH increase | ||

| Musculoskeletal | Weakness muscle cramps and myopathy | Rhabdomyolysis (if abuse of laxatives and diuretics) | Hypokalaemia and signs of dehydration |

| Dark urine | CPK elevation | ||

| Stress fractures | |||

| BMD decrease | |||

| Cardiovascular | Dizziness, syncope palpitations, chest pain | Oedema | If hypokalaemia |

| Bradycardia | |||

| Arrhythmias (Torsade de pointes if laxative abuse) | If hypokalaemia | ||

| QT interval prolongation | |||

| Orthostatic hypotension | |||

| Difficulty breathing | |||

| Haematological | Alterations in immunity | Anaemia or pancytopaenia | |

| Dermatological | Hair loss | Dry skin | |

| Lanugo | |||

| Russell's sign (calluses on the knuckles) | |||

| Hypercarotinaemia | |||

| Poor wound healing | |||

| Neuropsychiatric | Loss of memory or concentration | Seizures | |

| Depression or anxiety or Insomnia | |||

| Genitourinary | Hydroelectrolytic alterations | Nephrocalcinosis (if abuse of diuretics e.g., furosemide) | Hypokalaemia (vomiting) |

| Cramps | Alteration in abnormal and sediment | ||

| Increased creatinine (if laxative abuse) | |||

| Loss of chloride and potassium by diuretics |

BN: bulimia nerviosa; CPK: creatine phosphokinase; BMD: low bone mineral density; GH: growth hormone; FSH: follicle-stimulating hormone; LH: luteinizing hormone; GER: gastroesophageal reflux; PCOS: polycystic ovary syndrome; ED: eating disorders.

We will briefly focus on the main endocrine-metabolic alterations that can develop in athletes with eating disorders.

Menstrual disturbancesAmenorrhoea or menstrual alteration is a symptom that should always be investigated in all female athletes. For decades, it has been understood that women who are exposed to a high load of persistent physical training associated with deficient nutrition have a higher risk of presenting with alterations in the reproductive sphere, specifically oligomenorrhoea, primary (absence of menstruation >15 years) or secondary (no menstruation for three consecutive months) amenorrhoea.15 Maintained low energy availability (LEA) is what conditions an alteration in the hypothalamic pulsatility of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which causes a decrease in the release of pituitary follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), with the consequent decrease of oestradiol and progesterone, which is known as functional hypothalamic amenorrhoea. This LEA occurs when the energy ingested is insufficient to maintain the physiological functions of the body and those of physical training, which occurs when caloric intake is less than <30 kcal/kg/day of fat-free mass in women and under 20–25 kcal/kg/day in men.16 However, the duration and severity of LEA that must exist in order to produce these hormonal alterations is unknown.17

Decreased bone massLow intake also directly affects bone health, primarily in female athletes. In athletes, low bone mineral density (BMD) is defined as a Z score between -1.0 and -2.0 standard deviations associated with low intake, hypoestrogenism or stress fracture, and osteoporosis when the Z score is below -2.18 This LEA, along with the decrease in oestrogens secondary to amenorrhoea, are responsible for the bone fragility that athletes with EDs present with, which, added to calcium and vitamin D deficiency, increases the risk of stress fractures.19 An important factor that influences the BMD of female athletes is the age at which they start training. Thus, the negative effect on bone is greater the earlier the start of vigorous training.20 Stress fractures can affect different locations such as the neck of the femur, patella, medial malleolus, talus, scaphoid and sesamoid, among others, and impact female athletes who practice any discipline, but especially those for whom thinness is promoted.21

The presence in female athletes of alterations in menstrual function, bone mass and LEA is what is typically known as the female athlete triad.22 LEA is the main aetiopathogenic factor that generates these negative effects on bone and reproductive health.22,23 A multitude of studies carried out on women reflect this energy deficit in their usual intakes.23 The sports activities with the highest risk for the development of this female triad are all those that emphasise thinness, aesthetics and endurance sports, although this triad is present in all disciplines and at all levels of competition.24 The cornerstone of treatment is to improve and restore energy balance.25

HypogonadismIn men who practice intense and sustained resistance exercises such as marathon runners, cyclists, runners or those who do triathlon, alterations have been detected in the reproductive hormonal sphere.26,27 These include a decrease in the values of free testosterone associated with an alteration in the values of prolactin (PRL) and LH, as well as alterations in the pulsatility of the latter. This situation, which has a low prevalence among athletes, is known as “exercise-induced male hypogonadism” and was described by Hackney.28 The physiological mechanism of this hormonal reduction is unclear, but it appears to be secondary to dysfunction within the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal regulatory axis.29 This decrease in testosterone levels conditions an alteration in the androgenic processes dependent on this hormone. Thus, in some cases a decrease in spermatogenesis,30 decreased libido and impaired fertility is detected.31 Therefore, endocrinologists or fertility specialists should be aware of this problem that male athletes may present with.

Other associated endocrine disordersLEA is responsible for other hormonal alterations in addition to those previously mentioned regarding the involvement of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. In female athletes, alterations in thyroid function (inhibition of thyroid hormone release), changes in the levels of hormones that regulate appetite (decreased leptin and oxytocin and increased ghrelin, peptide YY and adiponectin), growth hormone (GH) resistance or relative hypercortisolism have been detected.32,33 It is likely that many of these hormonal disturbances occur to safeguard vital bodily functions.34

Nutritional deficienciesMicro and macronutrient deficiencies secondary to inadequate intake35 and stress induced by physical activity can also be detected. Among female athletes there is a notable interest in some micronutrients such as calcium, vitamin D, zinc, magnesium or B-group vitamins.36 Especially noteworthy is the case of calcium and vitamin D, given that, among this group, data on vitamin D insufficiency of 33% to 42% and inadequate intakes of calcium of 72% to 90% have been seen.36 Regarding macronutrients, alterations in glucose metabolism have been detected.

A common entity for male and female athletes and that encompasses the physiological consequences of LEA is the relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S) defined by the International Olympic Committee.17 This is characterised by an energy intake too low to maintain optimal body functions that provide health and correct sports performance. This syndrome, which includes the female athlete triad, encompasses alterations in metabolic rate, menstrual function, immune function, bone health, cardiovascular and protein synthesis.17

For all of the above, the sports performance of athletes with eating disorders is compromised.37 LEA leads to loss of lean and fat mass, decreased glycogen stores, micronutrient deficiencies38 and if there are purges, hydroelectrolytic alterations and a decrease in body fluids. In addition, athletes have decreased concentration, coordination, irritability, depression and increased risk of injury.17 All this negatively affects muscle power, resistance and consequently performance.39

The negative consequences for health that these pathologies can entail justify close monitoring of the nutritional status of athletes and the proper identification of all those who are at risk of presenting with alterations in eating behaviour or who already present clinical symptoms of a manifest ED.

ED-risk sportsAs stated above, the different studies reveal that athletes are at a higher risk of presenting with EDs or eating behaviour disorders compared to non-athletes in all age groups and in both sexes.40 But, in addition, depending on the activity that is practised, the risk changes. The sports in which there is a higher prevalence for the appearance of EDs are those activities in which there is pressure to lose and/or maintain weight.41 These can be divided into four groups where the appearance of these disorders is more common10:

- •

Sports where low weight is a competitive advantage and also where aesthetics are important: artistic gymnastics, figure skating or classical ballet. In modalities such as synchronised swimming or figure skating, a low weight is beneficial, since the figure of the athletes is considered deeply by the judges.

- •

Sports where low weight improves sports performance: canoeists or rowers. Recently, in a 2019 study, it was concluded that water polo, a sport that emphasises thinness and body weight control, is associated with a greater tendency to develop EDs, compared to other team sports.42

- •

Endurance sports. Endurance athletes benefit from a low weight in their performance (for example: marathon, swimming, cycling, etc.)

- •

Sports in which subjects are classified into weight categories (for example: boxing, weightlifting, taekwondo, powerlifting, etc.). In these disciplines it is necessary to stay within certain weight ranges for the competition.

It is well known that the aetiology of EDs is biopsychosocial, involving biological, genetic, psychological, family and sociocultural factors. The emphasis and value that our society places on thin bodies, especially in women, probably contributes to the development and prevalence of these disorders, acting as precipitating and maintaining factors. Thinness has become a metaphor for success, and excess weight for failure; thus, extreme thinness and beauty have been postulated as synonymous with success in this competitive society.

In addition to the type of sport that is practised, there are risk factors specific to the practice that increase the risk of presenting with an ED. Among them, the following stand out: the age at which training begins, the intrinsic regulation of each sport, especially those that emphasise strict weight control, the influence of the sports environment, the pressure to lose weight and injuries, among others.11

The identification of risk factors that make athletes more vulnerable, that is, those conditions or factors that trigger pathological behaviour; is a key point.43,44 In this sense, and added to the factors typical of EDs in general specific risk factors in athletes that should be taken into account in this population sector have recently been identified.45 Among them; the acceptance of the regulations of each discipline; the attitude of coaches; the pressure to achieve concrete achievements at the performance level; close assessment of weight status and body composition; public exposure of results and "brands" in training environments and media and social pressure (perceived or real) to be a certain way. These factors can specifically condition athletes who are vulnerable to EDs.

Another factor to take into account is following a strict dietary regimen for long periods of time, which is a predominant characteristic of athletes at amateur levels and those in competitions, a fundamental factor in precipitating the appearance of an ED, as already demonstrated by the classic study on the effects of starvation on the body by Keys et al. published in 1950.46

Sometimes, an athlete predisposed to this type of pathology can choose (consciously or unconsciously) a specific type of activity that "serves" to maintain it and thus the sports brands and challenges (desirable, due to the practice itself), become vehicle that maintains the disorder.47

Another fundamental role, as we have mentioned, would be played by the coach as a reference for their athletes, as they are able to exert direct pressure on athletes' dietary habits and body weight, relating weight and performance. And also indirectly, that is, maintaining diets without supervision, as was demonstrated in a significant number of Spanish athletes in the study by Toro et al. 2005,48 in which the desires of the athletes themselves to please their coach in terms of tastes and eating patterns were added. And in the study by Brooks et al.49 in which it was demonstrated that the diets proposed by coaches do not usually meet the nutritional requirements of the practised modality.

Coaches should motivate athletes to maintain a stable weight within the standards required in their discipline, prioritising health versus performance. It could even be recommended that a sport more in line with their body type be chosen, or even to rethink the one they practise, in case it is restricting their recovery process, as suggested by Baum.47

Finally, the key role played by family in EDs in general must be highlighted; a certain subtype of family with athletic children has been described,50 that may predispose to a higher probability of developing an ED. Some of these factors would include poor communication, inability to resolve conflicts, parental overprotection, rigidity and lack of flexibility to face new situations, absence of generational limits, excessively high expectations of parents in relation to their children and a history of mental health issues. On the other hand, two fundamental factors mentioned by Alonso should be considered50 in these types of families: firstly, the fact that parents/families tend to accept the measures adopted to regulate weight as part of their training requirements with good grace and secondly, the fundamental role they play when it comes to requesting specialised help given the lack of awareness of the disease of the affected athlete.

Comprehensive approach to athletes with EDsThe proposed comprehensive approach to athletes with ED, in light of the available literature, could be specified in the following points:

- 1

Promulgate the use of screening tools that allow us to diagnose these alterations early. The Eating Attitudes Test tool could be considered, in its abbreviated version EAT-26 to carry out an early screening for these alterations in eating behaviour in this at-risk population. The EAT test for attitudes towards food evaluates the fear of gaining weight, as well as restrictive eating patterns. In this sense, the Brief Eating Disorders in Athletes Questionnaire51 (BEDA-Q) tool and the Exercise Orientation Questionnaire (EOQ) could be considered, the latter is specifically designed for the identification of athletes at risk,52 focusing on attitudes and behaviours and allowing this type of population to be identified. The Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire 6.0 (EDE-Q 6.0) could also be considered in the assessment of athletes.45 All these questionnaires have some limitations, especially for male athletes, and they are self-reported, so the information they provide should be proven.53

Various American medical professional organisations have developed a monograph called Preparticipation Physical Examination (PPE) that includes a battery of questions aimed at identifying these disorders in athletes.54 In addition, it adds various questions about the negative consequences of these disorders such as menstrual disorders in women or stress fractures. Appendix 1 contains this abbreviated PPE in its Spanish version.

For female athletes, a more detailed questionnaire of 11 questions could be given to identify those who may present with the female athlete triad.22

- 2

The use of these screening tools will help to identify and detect these disorders early in athletes, which is especially important as this is associated with better treatment outcomes12 and a better evolution. This implies that all the professionals who are around the athlete must have excellent training on these disorders and recognise the signs and symptoms that may present themselves, as well as the consequences for the health of the athlete.

- 3

Once diagnosed, the next step would be to define where specific treatment will be carried out. Depending on the nutritional status of the patient, the healthcare setting may be different. It is recommended that the treatment be outpatient treatment as a general rule. Hospital admission should be considered in significant life-threatening circumstances, or with extreme malnutrition55 or situations of severe bradycardia, marked hypotension or severe electrolyte disturbances.22,40

- 4

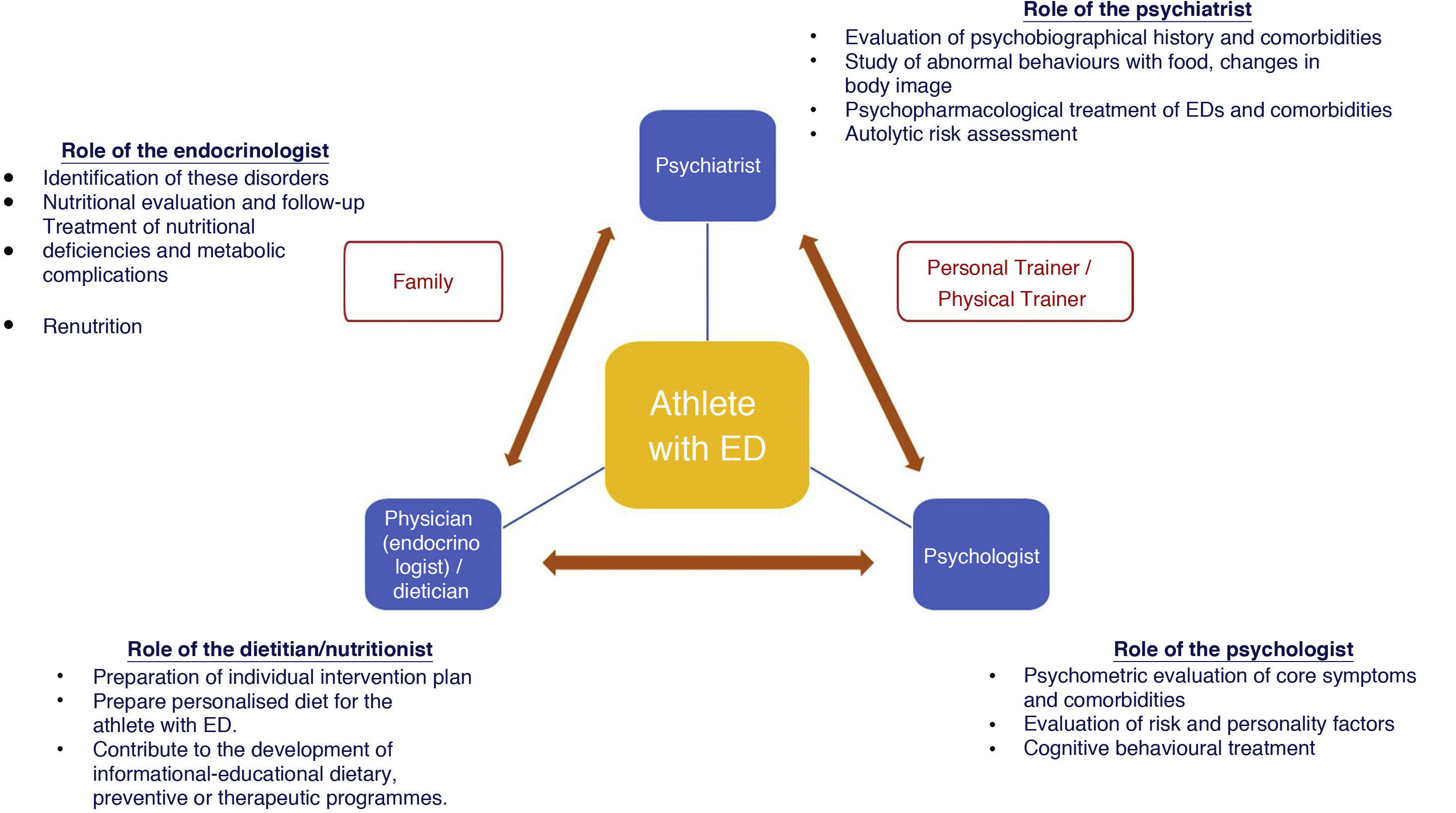

Athletes with EDs should undergo a thorough evaluation and treatment by an experienced multidisciplinary team once the diagnosis has been established. This interdisciplinary team should be made up of a general practitioner or specialist in sports medicine, a specialist in endocrinology and nutrition (as an expert in the management of patients with EDs), a dietician/nutritionist, a mental health team: psychiatrist/psychologist, physical trainers and the coaches themselves. The role of the coach is important to motivate the athlete to maintain a stable weight within the patterns required in their discipline, placing greater emphasis on the underlying health condition than on their performance.56 The role of parents would also be relevant in the case of adolescents.57,58Fig. 1 below illustrates this therapeutic approach and includes the main roles of people who care for athletes with EDs. It is interesting to note that the entire strategy is centred on the athlete.

Figure 1.Multidisciplinary treatment and role of the team members that care for an athlete with EDs. Modified from Joy E et al.40

(0.4MB).

The treatment of this entity is complex, it requires the joint work of the entire interdisciplinary team and needs to be done early to avoid chronification.

This team must establish what the therapeutic objectives are in each individual case. From the nutritional point of view, an early nutritional intervention is of interest that seeks to reverse the situation to normalise the eating pattern. Other goals that should be set include:

- none-

Setting attainable goals in the short, medium and long term.

- none-

Establishing a minimum energy content and defining the composition of an adequate and healthy diet.

- none-

Correcting erroneous eating behaviours.

The objectives of the mental health-psychiatry team will assess the most suitable type of psychotherapeutic intervention to correct the athlete's psychological and behavioural alterations:

- •

From the outset, awareness of the disease and the introspective capacity of the patient will be addressed, motivating him or her to change; attempting to re-establish a regular eating pattern, through the use of cognitive and behavioural techniques, as well as an approach to the cognitive distortions typical of the disorder regarding figure, weight and food; and also baseline personality characteristics such as low self-esteem and a tendency toward perfectionism.

- •

Providing them with emotional and psychological support to help them manage the stress of losing and/or maintaining their weight.

- •

Addressing the serious alterations in body image reported by patients that are manifested in body dissatisfaction/distortion and have a negative impact on the eating disorder.

- •

Reorganisation of family, social, sports dynamics (coaches, teammates, etc.) is equally important to achieve the objectives described above.

- •

In addition, another of the key characteristics is that follow-up is carried out on a regular basis, including a psychological and nutritional evaluation.59

- 1

Nutritional education is key in the management of athletes with EDs.60 It is essential to transmit individualised dietary advice and also provide information so that the athlete adopts a change in their eating pattern that is maintained in the long term. For this reason, group sessions should be implemented on different aspects of sports nutrition but also that are personalised, focused on the patient to treat the irrational beliefs about food that the athlete has. Offering training sessions to coaches and parents could be useful. It is well-known that a coach can increase or decrease the risk of developing this pathology.61

The importance of the dietitian/nutritionist (certified in sports nutrition) regarding nutritional advice is fundamental.62–64 His/her role is key in the development of the individual intervention plan and in the preparation of a personalised diet for the athlete with EDs.65 He/she would also collaborate in the development of informative and educational dietary programmes, both preventive and therapeutic, when the ED is established. It would be useful to carry out structured interviews with certain periodicity to detect patterns of reduced intake, as well as alterations in eating behaviour of decreased intake and also other issues such as constant concern about food, excessive time eating or changing the athlete's manner of eating. It is also important to understand the athlete's eating habits and how they have evolved over time. This nutritional treatment would have two phases: at first, the educational phase: where a plan is drawn up to transmit knowledge about nutrition and dietetics to the athlete and in the second phase, the previously prepared educational plan would be put into practice, attempting to modify the eating behaviour.63,66

- 6

The clinical, anthropometric and analytical evaluation of athletes with eating disorders is a key aspect of their initial evaluation and in their follow-up.

From an anthropometric point of view, the most universal measure used to determine low body weight is the body mass index (BMI) (weight kg/height m2), although absolute BMI cut-off points should not be used for adolescents, for whom the use of expected body weight is preferable.17,40

Body composition techniques such as bioimpedance measurement, or the Bod Pod®, may provide information for the evaluation of these patients. However, according to the latest position from the American and Canadian academies of dieticians and the American College of Sports Medicine, they should not be used to calculate a specific target body fat percentage for individual athletes, nor should they be used to select athletes for the different teams.38,67

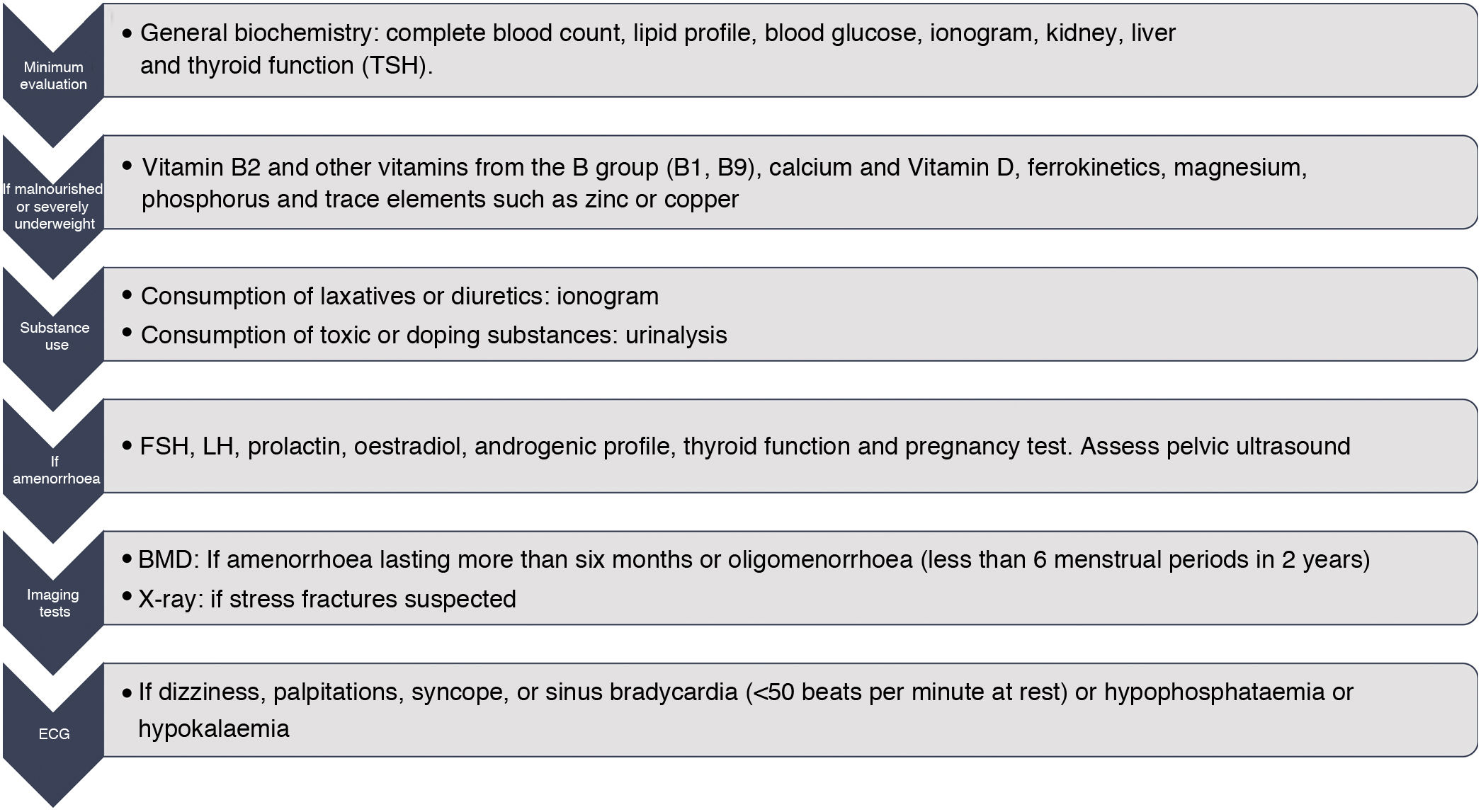

Laboratory test evaluations should include, among other parameters, general biochemistry including complete blood count, lipid profile, ionogram, renal, hepatic and thyroid (TSH) function. The additional determination of the levels of Vitamin B12, calcium and Vitamin D, zinc, ferrokinetics, magnesium38 and phosphorus would also be relevant in cases of malnutrition or poor nutritional intake. In case of amenorrhoea, the determination of FSH, LH, PRL, oestradiol, androgenic profile, TSH and pregnancy test would be of interest. Carrying out a densitometry would be indicated in those cases of women with amenorrhoea lasting more than six months or oligomenorrhoea (less than six menstrual periods in two years). In those athletes at risk of low BMD or who are receiving specific treatment, it is advisable to repeat the BMD every year in the case of adults and a minimum of six months in adolescents.68 The performance of an electrocardiogram (ECG) would be indicated in those athletes with symptoms of dizziness, palpitations, syncope or sinus bradycardia (<50 bpm at rest).40Fig. 2 collects the laboratory determinations and tests to be carried out in the athlete with EDs. In addition, it will be necessary to re-evaluate compliance with the proposed dietary plan, changes in weight and analytical parameters, menstrual cyclicity, and bone health throughout the follow-up.

- 7

Medical treatment for the physical complications that these athletes may experience is another point to consider.

If athletes with EDs present with amenorrhoea, the initial treatment will include increasing total caloric intake and reducing or ceasing the practice of physical exercise,24 since if this remains excessive, amenorrhoea can become chronic. This increase in caloric intake should be greater in adolescents. An adequate intake of carbohydrates and proteins is recommended to restore hepatic glycogen stores and thus facilitate LH pulsatility.69,70 Weight regain when 90% of ideal body weight is reached can help restore menstrual cyclicity, because weight gain is the primary predictor of the restoration of menstrual cyclicity and is, therefore, the first line of treatment.71–73 Regarding pharmacological therapy, the systematic use of oral contraceptives (OC) is not recommended for the recovery of menstruation.17 In addition, its use could mask menstrual alterations and also would not protect the loss of bone mass.17 The start of transdermal oestrogen therapy for a short period of time could be considered if amenorrhoea persists despite weight recovery, changes in the pattern of physical exercise and psychological intervention.74 This transdermal therapy will also help protect BMD. All these therapeutic measures explained above are recommended to be started in the first year of onset of amenorrhoea.24

Treatment of low bone mass is essential to normalise body weight and menstrual cyclicity of athletes with ED in order to increase it. From a practical point of view, for a woman with insufficient nutritional intake, amenorrhoea and/or low BMD, a calcium intake of 1,500 mg/day is recommended36 associated with the consumption of vitamin D (600 IU/day) to improve bone health and calcium absorption. Regarding pharmacological therapy, the use of bisphosphonates in athletes of reproductive age is not recommended, since these are stored in the bone for long periods of time and can be teratogenic.75,76 Other drugs such as raloxifene, teriparatide, or calcitonin are not approved for premenopausal female athletes. In men with osteoporosis, bisphosphonates, denosumab, or strontium ranelate will increase BMD,77 although testosterone replacement therapy itself in patients with hypogonadism will improve BMD. In addition to these pharmacological therapies, those who practice disciplines with low osteogenic impact such as swimming or cycling will be recommended an exercise programme (jumps) that increase the mechanical load on the bones.45

In the sports world, the use of nutritional supplements such as vitamins, minerals, herbal products, energy drinks, creatine, hydroxymethylbutyrate, glutamine, essential amino acids or ginseng, among others, is widespread because their consumption is associated with an improvement in sports performance.78 When vitamin deficits are detected, it is suggested that their supplementation be reserved for young athletes only,38 provided that it is confirmed that these supplements are validated and free of impurities and doping substances. These prohibited substances are collected by the World Anti-Doping Agency in a list of doping substances in sports practice.79 In recent years, the magnitude of the abuse of this type of supplements among the youngest of athletes has increased, it being necessary to carry out strict measures. These must be directed in an interdisciplinary manner by the different health professionals, contributing to the development of educational, preventive and therapeutic programmes that reduce the spread of doping and its dissemination to populations at risk, such as those with EDs.80 In this sense, to reduce these dangerous behaviours, teachers, coaches, doctors, dietitians-nutritionists, sports organisations, etc. must be aware of the existence of this problem among the youngest of athletes, and contribute to its solution through the implementation of said programmes.81

- 8

Pharmacological treatment of psychological/psychiatric complications in EDs

There are only two psychopharmaceuticals authorised by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the American Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the direct treatment of EDs. In the case of BN, it is accepted that fluoxetine exists as a specific treatment. This antidepressant is effective in reducing symptoms at doses of 60 mg/day in one or three doses, even though there is no associated depression. Lisdexamfetamine is licensed for use in patients with binge eating disorder.

In the case of AN there is no specific pharmacological treatment, but only that of its psychiatric complications. It is recommended that antidepressant drugs be prescribed, in usual doses, if there is an associated depressive picture that does not improve with renutrition. The use of anxiolytics is convenient in cases of comorbidity with anxiety disorders. In obsessive-compulsive disorders (OCD) and disorders with panic attacks, they should be associated with antidepressants.40

- 9

Another aspect to take into account would be when suspension and reinstatement of the sports practice should be indicated.

From the Norwegian Olympic Sports Centre and the Committee of Experts of the International Olympic Committee, criteria have been developed that are based on a colour-coded system (red/yellow/green) that guide the multidisciplinary team that works with the athletes in the evaluation of the risk of practising sports. Thus, for individuals who are at high risk, represented by red, participation in sports should not be authorised. Those who fall under this category have been diagnosed with AN and other serious EDs82 (for example, more than four purges/day in the case of BN12) or are those individuals with significant medical problems derived from their low energy availability (LEA) or are those who use techniques to facilitate weight loss (e.g., diuretics) that cause marked dehydration, haemodynamic instability or a life-threatening risk. Athletes at moderate risk (represented in yellow) can return to sports practice under medical supervision and with a defined treatment plan. Included in this group are those who do not have defined criteria for EDs but who do have some characteristics such as: significant weight loss (5%–10% in a month), menstrual alterations, menarche beyond 16 years of age, decreased bone mass, history of one or more stress fractures associated with hormonal or menstrual changes, or changes in laboratory test results or in the ECG, among others.

In addition, if an athlete with EDs refuses to receive the treatment indicated by the multidisciplinary team or does not comply with all the proposed indications, he or she would not be able to return to training either.24 This implies that the athlete must comply with the dietary plan designed by the dietician, achieve the weight gain goals set and, in addition, that there is no clinical risk to his or her health with the return to training (syncope or bradycardia).24

The criteria for restarting sports practice will be based on the evaluation of the athlete's health and the requirements of the activity practised. The International Olympic Committee also proposes a system based on colours according to clinical symptoms, so that athletes can return to practice.47 In addition, in 2014 a position statement was proposed by the Female Athlete Trial Coalition Consensus Statement that could serve as a guide for clinicians to make decisions about returning to sports practice.12 Normality in dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) can mark a return to sports practice despite irregular menstrual cycles.24 For now, there are no such defined recommendations for male athletes.

PreventionAfter the above, the highest priority would therefore be the prevention of these alterations among athletes, which constitutes a real challenge. Efforts should not only be directed at their primary prevention but also at avoiding relapses (secondary prevention).

The ED-athlete binomial should not be considered a taboo subject among this group. All the publications consulted in this regard insist on the importance of delving into the concept of healthy nutrition by athletes, training them on the signs and symptoms of these diseases, as well as their consequences, and giving guidelines for action when faced with the first symptoms of suspicion about onset in a teammate.18,83

Another important aspect to take into account would be the role coaches play in these pathologies. They should have sufficient knowledge about these entities, be aware of the main risk factors and precipitants for their development53 and about their management.84 Carrying out specific training in these pathologies that enables coaches to identify the psychological factors that play a crucial role in the development of EDs as part of their curricular training could be an option to consider.

Establishing annual mandatory educational programmes for athletes, their coaches and physical trainers53 is a measure to be conceived within the sporting context.

It is useful, furthermore, to demystify false beliefs in relation to body-weight-sports performance, as we have commented on previously, with a tendency to focus more on information about correct nutritional habits, and offer contrasting data as suggested by Thompson, in 1993,85 rather than focusing on a detailed explanation of the disorders whose appearance is intended to be avoided. It is also paramount that the family receives good information about healthy eating habits as a means of preventing abnormal behaviours related to eating in general, and also with the minimum healthy requirements required by the specific discipline that their family member practises.

The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) is an American association made up of multiple institutions and organisations that implement most of the university sports programmes in the United States. This association has created specific material for the athletes themselves and their coaches with a view to preventing these pathologies.86 In addition, the American National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA) has developed several specific recommendations for coaches.87

ConclusionIn summary, EDs are diseases with a significant impact on sports activity both due to their prevalence and the increased risk of comorbidities and associated complications. Screening for EDs and their consequences should be indisputable components of pre-competition evaluations and team doctors should be familiar with updates to current diagnostic manuals (ICD-10, and DSM-5). Athletes with EDs should be evaluated and cared for in specialised multidisciplinary teams and receive early comprehensive treatment. From the outset, awareness of the disease and the introspective capacity of the patient will be addressed, motivating him or her to make a change. The doctor responsible for the team would play a critical role in making decisions regarding the appropriateness of the patient's return to training and the best time for it. More research is advocated for EDs in general and in particular for athletes who suffer from them in order to make epidemiological and aetiological advances regarding these disorders and effectively improve prevention, as well as establish more specific treatment strategies in the athlete population, including gender differences. The journey back from an ED is a complicated and bumpy road. Parents, coaches, health professionals, sports managers and society in general must challenge ourselves in this 21 st century to the acquisition of a healthy lifestyle for our child and adolescent athletes, and focus on transmitting knowledge in relation to the fundamental balance that exists between healthy eating and proper training.21

FundingWork on this document has not received funding from any source.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Marí-Sanchis A, Burgos-Balmaseda J, Hidalgo-Borrajo R. Trastornos de conducta alimentaria en la práctica deportiva. Actualización y propuesta de abordaje integral. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2022;69:131–143.