The prevalence of dysphagia in hospitalized patients is extraordinarily high and little known. The goal of care should be to assess the efficacy and safety of swallowing, to indicate personalized nutritional therapy. The development of Dysphagia Units, as a multidisciplinary team, facilitates comprehensive care for this type of patient.

Material and methodsA observational, cross-sectional, web-based survey-type study, focused on Spanish Society of Endocrinology and Nutrition department heads, was conducted in September-October 2021. The following data were analyzed: size and type of center, existence of a dysphagia unit, dysphagia screening, dietary and nutritional therapy, education and training of professionals and patients, codification, and quality of life evaluation.

Results65 responses (39% of the total Endocrinology and Nutrition departments). 37% of hospitals have a Dysphagia Unit and 25% are developing it. 75.4% perform screening, with MECV-V in 80.6%, and VED (61.4%) and VFS (54.4%) are performed as main complementary tests. The centers have different models of oral diet, thickeners and nutritional oral supplements adapted to dysphagia. In 40% of the centers, no information is offered on dysphagia, nor on the use of thickeners, dysphagia is coded in 81%, 52.3% have specific nursing protocols and only 8% have scales for quality-of-life evaluation.

ConclusionsThe high prevalence and the risk of serious complications require early and multidisciplinary management at the hospital level. The information received by the patient and caregiver about the dietary adaptations they need, is essential to minimize risks and improve quality of life.

La prevalencia de disfagia en pacientes hospitalizados es extraordinariamente elevada y poco conocida. El objetivo asistencial debe ser evaluar la eficacia y la seguridad de la deglución, para indicar un tratamiento nutricional personalizado. El desarrollo de Unidades de Disfagia, constituidas por equipos multidisciplinares, facilita una asistencia integral a este tipo de pacientes.

Material y métodosEstudio observacional transversal tipo encuesta vía web, dirigida a los jefes de servicio de la SEEN, realizado en septiembre-octubre de 2021. Se analizaron: tamaño y tipo de centro, existencia de Unidad de Disfagia, cribado de disfagia, tratamiento dietético y nutricional, formación y capacitación de profesionales y pacientes, codificación y evaluación de la calidad de vida.

ResultadosSesenta y cinco respuestas (39% de Servicios de Endocrinología y Nutrición). El 37% de los hospitales disponen de Unidad de Disfagia y en el 25% está en desarrollo. El 75,4% realiza cribado, con MECV-V en el 80,6%, y se realizan evaluación fibroscópica de la deglución (61,4%) y videofluoroscopia (54,4%) como pruebas complementarias principales. Los centros disponen de distintos modelos de dieta oral, espesantes y suplementos nutricionales adaptados a disfagia. En el 40% de los centros no se ofrece información sobre disfagia ni sobre el uso de espesantes, se codifica la disfagia en el 81%, el 52,3% disponen de protocolos de enfermería específicos y solo en el 8% se registran escalas de calidad de vida.

ConclusionesLa alta prevalencia y el riesgo de complicaciones graves exigen un manejo precoz y multidisciplinar a nivel hospitalario. La información que reciben el paciente y el cuidador sobre las adaptaciones dietéticas que precisa es fundamental para minimizar los riesgos y mejorar la calidad de vida.

Oropharyngeal dysphagia (OPD) is a disorder recognised by the World Gastroenterology Organisation, characterised by difficulties in safely and effectively moving the food bolus from the mouth to the oesophagus.1 This situation increases the probability of malnutrition, dehydration and pulmonary aspiration, with a consequent worsening of the patient's clinical situation, prognosis and quality of life.

OPD is a relatively common symptom that occurs in approximately 3% of the general population and can affect, depending on the type of coding used, 24–30.7% of hospitalised patients.2,3 The incidence of OPD increases with age, in such a way that between 10% and 30% of those over 65 years of age present some type of difficulty in swallowing,4 and it can affect up to 82.4% in series of patients over 80 years of age.5 The prevalence of OPD described after a stroke ranges from 22% to 70%, depending on the criteria used to define it, the evaluation method and the time since the stroke. Prevalence is higher in cases of haemorrhagic stroke and in those with combined involvement of the trunk and hemispheres.6

Patients with traumatic brain injury present OPD in 30% of cases, while in Parkinson's disease, the prevalence can reach 81%.7 In the case of dementias, 13–57% present with OPD, in multiple sclerosis 31.3% and in patients with motor neuron disease 30-100% may present dysphagia.6 Without forgetting the group of patients who present sequelae of surgery for head and neck tumours, or those of radiotherapy.7

The objective of this article is to explain the reality of care at the hospital level for patients with OPD and to propose, from the Management Committee of the Nutrition Area of the SEEN, a series of recommendations for routine clinical practice that will help to optimise care, reduce variability between hospitals and improve the quality of life of patients.

Material and methodsThe study was a cross-sectional observational study designed as a web-based survey. A team from the Management Committee of the Nutrition Area of the SEEN, with experience in the management of hospitalised patients with dysphagia, designed a questionnaire to achieve the objectives of the study. This questionnaire was sent by email from the SEEN secretariat to the heads of Endocrinology and Nutrition departments, as well as members of the Nutrition Area who they encouraged to participate (one per department). All the data were anonymous and self-registered (the complete survey can be seen in the additional material, Appendix A Annex).

The main objective of this study was to analyse the hospital management of patients with dysphagia, in order to subsequently establish a series of recommendations to improve care and reduce variability in clinical practice.

To achieve this objective, respondents were asked about the following aspects: screening for dysphagia, disease-related malnutrition (DRM) and sarcopenia, dietary and nutritional treatment of dysphagia, education and training, coding and quality of life assessment.

Once the survey was agreed upon, it was made into to a form, using the Google Forms® tool for data collection and processing. The survey was open from 17 September to 8 October 2021.

The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki (October 2013), respecting the principles of Good Clinical Practice and European Legislation on Data Protection, EU 2016/679. The information about the survey was provided to the potential participants who were also offered the possibility of contacting the work team. The act of completing the online survey and sending the data was considered as consent for the analysis and interpretation of the data. The data was collected anonymously.

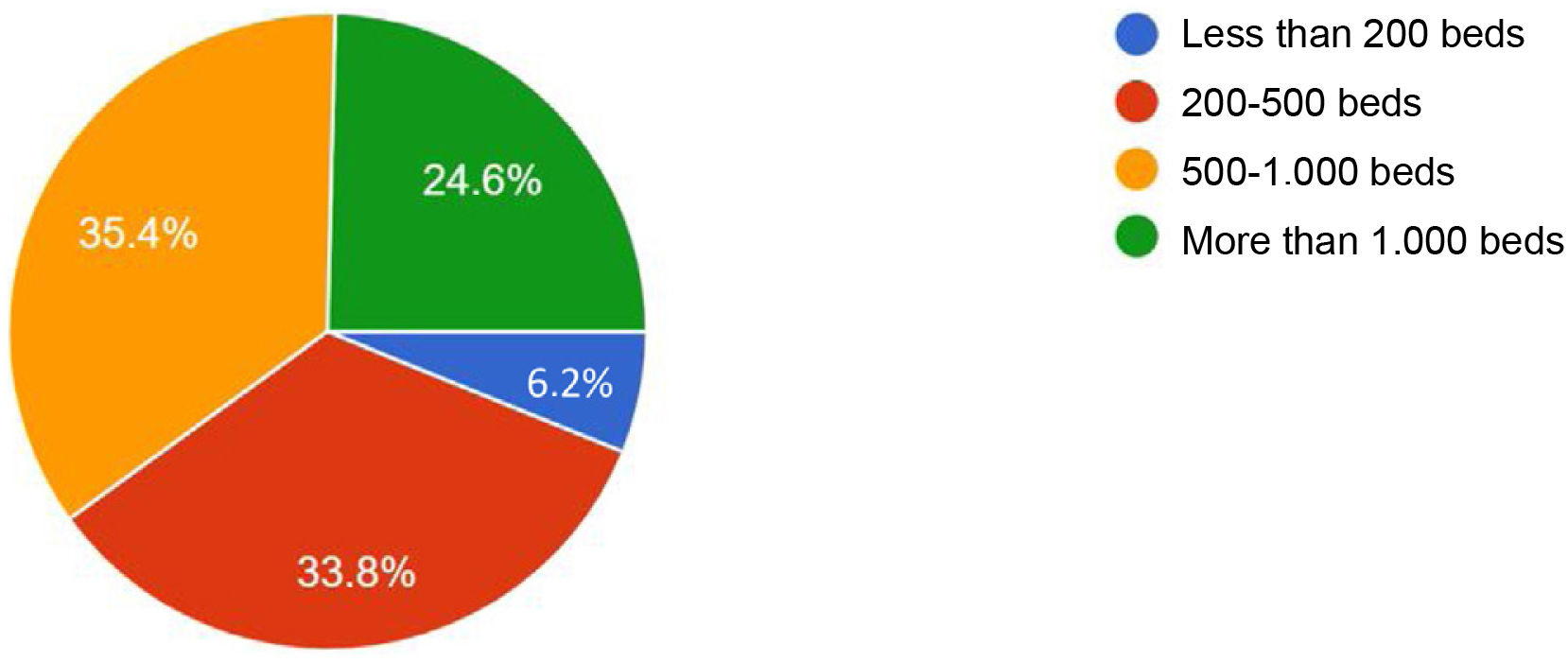

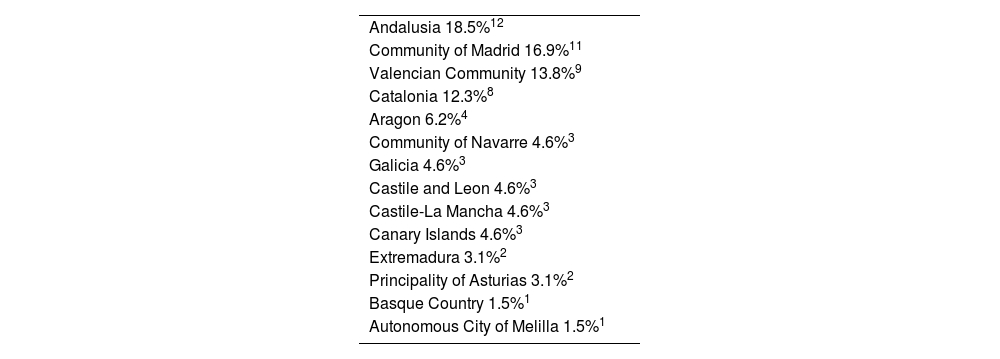

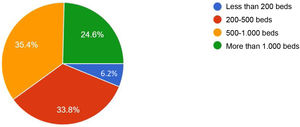

ResultsStudy populationA total of 65 responses were obtained, which represents the participation of 39% of Endocrinology and Nutrition departments. The representation by type of hospital and by autonomous communities can be seen in Fig. 1 and Table 1. Of the participating hospitals, 98% are public and in 94% there is a Clinical Nutrition and Dietetics Unit (CNDU).

Distribution by autonomous community.

| Andalusia 18.5%12 |

| Community of Madrid 16.9%11 |

| Valencian Community 13.8%9 |

| Catalonia 12.3%8 |

| Aragon 6.2%4 |

| Community of Navarre 4.6%3 |

| Galicia 4.6%3 |

| Castile and Leon 4.6%3 |

| Castile-La Mancha 4.6%3 |

| Canary Islands 4.6%3 |

| Extremadura 3.1%2 |

| Principality of Asturias 3.1%2 |

| Basque Country 1.5%1 |

| Autonomous City of Melilla 1.5%1 |

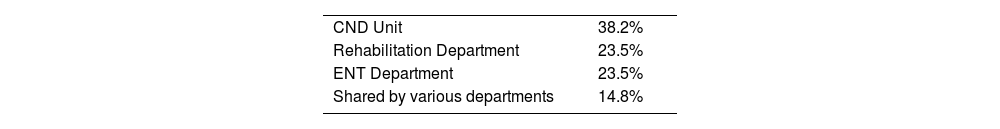

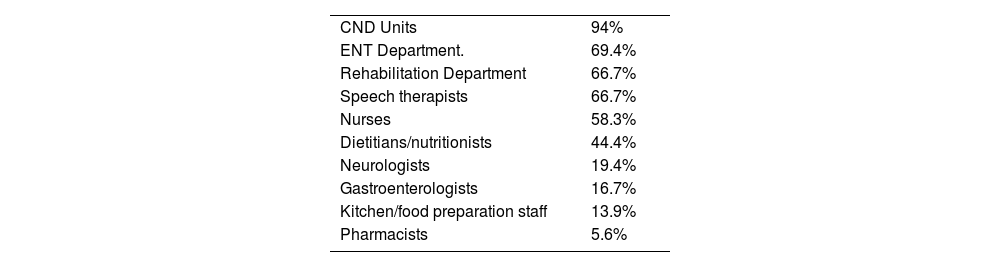

In relation to the availability of a Dysphagia Unit, 37% of hospitals have one, 25% are setting one up, and 38% do not have one. In those hospitals that have a Dysphagia Unit, 53% evaluate any type of dysphagia, 41% OPD and 6% structural dysphagia. In relation to the coordination and constitution of the Dysphagia Units, more information is detailed in Tables 2 and 3. The CNDU does not participate in only two Dysphagia Units.

Early identification of dysphagia prevents adverse health outcomes. However, there is no universal consensus on the best dysphagia screening tool. Generally, the objectives and plans are individualised to adjust to different clinical scenarios, with the participation of multidisciplinary teams.9 When selecting a type of screening, there are many factors that must be taken into account: patient age, ACVA location, other underlying diseases that can alter swallowing, polypharmacy, fluctuating level of consciousness, health staff lacking sensitivity with little training in swallowing disorders.10

The established and validated tests for the evaluation of dysphagia are:

- a.

Screening assessment: volume-viscosity clinical exploration method (MECV-V) or volume-viscosity swallow test (V-VST), Standardised Bedside Swallowing Assessment (SSA), water test combined with oximetry, Gugging Swallowing Screen (GUSS), 3-oz swallow water test, Toronto Bedside Swallowing Screening Test (TOR-BSST), Barnes-Jewish Hospital Stroke Dysphagia Screen (BJH-SDS, MMASA), Eating Assessment Tool-10 (EAT-10).11 They detect the risk of pulmonary aspiration associated with dysphagia and may reduce the need for clinical evaluation of swallowing or instrumental evaluations.

According to the survey, 75.4% of the hospitals carry out dysphagia screening, but only in some hospitalisation units (12.3%) do they carry out generalised screening throughout the centre and 12.3% do not carry out screening.

The screening is carried out by nurses from the CNDU (61.8%), nurses from the corresponding hospitalisation unit (52.7%), doctors from the CNDU (34.8%), doctors from other specialties (23.6%), dietitians/nutritionists (20%) or nurses from the Dysphagia Unit (16.4%). The most performed tests are MECV-V (80.6%) and EAT-10 (46.8%), while only 8.1% of the hospitals perform the water test combined with oximetry.

In most of the hospitals (77%), specific informed consent is not requested to perform these tests.

- b.

Instrumental evaluation: they are objective examinations, but at the same time more expensive, such as videofluoroscopy (VFS) or fibreoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES), among others.12

The European Society for Swallowing Disorders (ESSD) takes a position on the usefulness of diagnostic tests for the study of OPD and indicates a series of rules to follow13:

- -

Patients who screen positive for OPD or with poor airway protection should undergo instrumental evaluation, either VFS or FEES.

- -

VFS and FEES should be performed in a standardised manner, preferably with the patient in an upright position. The VFS should always include a lateral view of the oral cavity, pharynx and oesophagus.

- -

It is essential to have standardised protocols for performing VFS and FEES, taking into account that some patients will require individually designed tests.

- -

The diagnostic test should focus on the patient's worst swallowing to reveal the dysfunction or morphological abnormality that may explain the patient’s symptoms and should also serve to determine the methods by which the condition can best be corrected.

- -

The procedure must include manoeuvres and postures when necessary, as well as the use of different viscosities and textures, taking cultural differences into account.

- -

The VFS should be performed by a dysphagia expert together with a radiologist. The VFS must be performed at a capture rate of at least 25 frames per second.

To carry out complementary tests, the surveyed hospitals have: FEES (61.4%), VFS (54.4%), pharyngeal/oesophageal manometry (52.6%), oesophageal pH-metry (49.1%) and oesophageal impedance monitoring (12.3%). The most frequent combination of diagnostic tests available in hospitals that responded to the survey is FEES together with oesophageal pH-metry and pharyngeal/oesophageal manometry (37.8%), but in many cases they are not the only available techniques.

Nutritional treatment of dysphagia- a.

DRM and sarcopenia screening: it is known that malnutrition, significant loss of muscle mass and weight, sarcopenia, dehydration and bacterial respiratory superinfections are specific complications of dysphagia.14,15 Like the muscles of the extremities, the muscles related to swallowing can also be affected in patients with DRM. Sarcopenia has been found to be a risk factor for dysphagia.16,17

In relation to these comorbidities, the surveyed hospitals perform:

–DRM screening: 55% in a generalised way; 25% only in some hospitalisation units.

–Sarcopenia screening: 20% in a generalised way; 18% only in some hospitalisation units.

This survey did not ask about the screening method used for either of the two pathologies, since they were not the objectives of this study.

- b.

Oral diet: the texture of food and liquids must be adapted to the degree of OPD of the patient with the aim of, in addition to nourishing and hydrating, maintaining the pleasure of food.10 It is necessary to involve patients and caregivers in the entire process, informing them of the reasons for and types of modifications that should be carried out to achieve better therapeutic adherence. In addition, we cannot forget that periodic evaluations must be performed to confirm the degree and progression of the OPD, since in some patients the swallowing disorder can be reversed or worsen.

Malnutrition and dehydration are two of the complications that people with dysphagia can develop. To avoid them, it is necessary to establish nutritional treatment guidelines that cover the nutritional and hydration requirements of the patient, beginning with the adaptation of their usual diet. Dietary measures are aimed at offering an adequate, sufficient and safe diet both in terms of food textures and liquid viscosity.18–20 If this is insufficient, oral supplementation, enteral nutrition or parenteral nutrition should be continued, if necessary.

In relation to the hospital diet, in the hospitals surveyed they have an easy-to-chew diet (72.3%), handmade mashed diet (64.6%), pre-mashed diet (40%), high-protein mashed diet (32.3%), texture modified diet (18.5%) and all the above-mentioned options (18.5%).

- c.

Thickeners: patients with dysphagia have difficulties in achieving adequate hydration, since most of them have to modify the viscosity of liquids to achieve safe swallowing.21 Liquids must be thickened, through the use of thickeners, until the adequate viscosity is achieved, depending on the degree of severity of the dysphagia. In the composition of the thickeners, modified corn starch, dextrinomaltose or gums stand out, which, added to a liquid (water, juice, infusion, etc.), increase the viscosity depending on the amount added.22 The latest generation thickeners, made only with gums (guar gum, xanthan gum, etc.) are the most stable and the safest. Liquids can also be provided in the form of gelled waters (available in 43.1% of the hospitals), taking into account that these maintain stability at room temperature.

In the hospitals surveyed, 43% had gum-type thickeners, 11% starch-type thickeners, 45% both, and 1% were unaware of the type of thickener available. In relation to the format, 35% have jars, 32% have sachets and 32% both formats. The thickeners are supplied by the nursing staff of the hospitalisation unit (44.6%), the pharmacy (43.1%) or the kitchen (18.5%). The dosage/texture of the liquids is adjusted by 80% according to the results of the dysphagia test. At discharge, the thickeners appear in the discharge report and are prescribed by the CNDU doctor (53.1%), the doctor responsible for admission (37.5%), the nurse from Nutrition (25%) or the nurse from the Hospitalisation Unit (14.1%).

- d.

Oral nutritional supplements: when a patient with dysphagia is not able to cover their nutritional requirements through natural food or is in a situation of malnutrition, oral nutritional supplementation (ONS) should be considered.23 Nutritional supplements are chemically defined formulas composed of macro- and micro-nutrients, which are administered orally and serve to reinforce or modify the composition of a diet. In some cases, when enteral formulas are complete, they can be used as the only source of nutrients if the patient ingests enough to cover their nutritional requirements. In the surveyed hospitals, they have nectar texture ONS (47.7%), cream/pudding texture ONS (46.2%), all (49.2%) or none (6.2%).

After performing the dysphagia assessment and adapting the dietary and nutritional treatment, the patient, the family and the caregiver should receive all the recommendations for safe and effective feeding, instrumental adaptations if necessary, nutritional objectives and oral hygiene measures. In addition, they should be informed and warned about the signs of aspiration pneumonia, dietary adaptations and postural security measures that must be taken into account at home. Training and involving the patient in the management of their dysphagia helps them to be better prepared to face their disease and even prevent complications.24

In 40% of the hospitals surveyed, information on dysphagia or the use of thickeners is not offered, and in 60% it is only provided occasionally.

Coding and treatment at dischargeDysphagia is classified under the heading of "signs and symptoms" in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD10) with the code R13. A symptom such as dysphagia and a comorbidity such as malnutrition increase the complexity of patients who are treated at the hospital level and, therefore, the consumption of resources, as we can see in the attribution of the weights of the related diagnostic groups.25 According to the survey carried out, dysphagia is coded in 81% of the hospitals.

Nursing protocolsThe follow-up of patients with dysphagia, as well as the proposed therapeutic strategies, must be approached from a multidisciplinary point of view in which the Nursing department plays a fundamental role. Nurses should participate in the assessment of dysphagia (screening), the choice of the most appropriate diet, the training of patients and caregivers (viscosity of liquids, texture of food, security postures), providing quality care during admission to reduce possible complications derived from swallowing difficulties.

Once it has been confirmed that a patient has dysphagia, the following three essential types of care should be put in place26:

- 1.

Dietary, which, based on the information obtained with the aforementioned tests, and, provided that oral feeding is not contraindicated, begin with the prescription of a specific diet for dysphagia, with textures, volumes and viscosities adapted to the possibilities of chewing and swallowing of each patient.

- 2.

Postural, fundamentally focused on maintaining a sitting position and forward flexion of the head during eating and, in the case of hemiplegia, rotation towards the affected side.

- 3.

Training, which consists of instructing the caregivers of the patient in how to manage their dysphagia.

According to the survey carried out, 52.3% of the hospitals have specific nursing protocols for the management of dysphagia and, in relation to the training of health personnel, 58% have specific courses.

Quality of lifeDysphagia can cause increased anxiety and fear. Many patients avoid oral intake, which leads to malnutrition, isolation and depression. Understanding and balancing the potential risks and benefits of continuing oral intake or choosing to administer artificial nutrition makes this a complex and challenging area of healthcare.27

To date, there have been few specific questionnaires designed to assess the quality of life in patients with dysphagia. Among them are: the Swallowing Quality of Life Questionnaire (SWAL-QOL and SWAL-CARE), the MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory (MDADI) and the Dysphagia Handicap Index (DHI). All these instruments for measuring quality of life are useful for monitoring the progression of patients after undergoing treatments in order to manage the aetiology of dysphagia and to determine the effectiveness of the intervention.

According to the survey carried out, only 8% of the hospitals record quality of life scales in patients with dysphagia.

Changes in the context of the COVID-19 pandemicThe COVID-19 pandemic has led to multiple changes in the care and organisation of the health system.28 Up to 52% of patients admitted for COVID-19 had dysphagia, according to a study carried out at the Hospital de Mataró. Patients with OPD at discharge showed reduced survival at six months compared to those without OPD (71.6% vs. 92.9%, p < 0.001).29 Accepting this reality, many health centres have reorganised their teams and resources to improve the care of patients with dysphagia.

According to the survey carried out, in 57% of the hospitals the care of patients with dysphagia has changed during the pandemic, but in 34% only in the case of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

DiscussionTo manage all the needs of patients with dysphagia, it is essential to develop hospital Dysphagia Units, made up of well-coordinated multidisciplinary teams that fully cover the diagnostic and therapeutic needs of these patients. In Spain, we have as a reference the Oropharyngeal Dysphagia Functional Unit of the Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias [Príncipe de Asturias University Hospital] (in Alcalá de Henares), in which the different professionals of four structural units (ENT, Rehabilitation, CNDU and Hospital Kitchen), with a multidisciplinary vision of dysphagia based on their different skills and competencies, add value to the process by working closely together.10

Given the prevalence of dysphagia and the severity of the associated comorbidities (DRM, sarcopenia, dehydration, aspiration pneumonia), it is striking that in the autumn of 2021, 38% of the surveyed hospitals still did not have a Dysphagia Unit. It has been demonstrated that a hospital with just over 500 beds can have this type of unit, and we consider that the awareness and commitment of the hospital's management, as well as the training of health personnel, are fundamental as critical success factors.

Likewise, we cannot forget the necessary provision of resources and personnel. The portfolio of services of a Dysphagia Unit must include: directed clinical history, nutritional screening with the volume-viscosity method at bedside, instrumental tests (FEES, VFS), DRM and sarcopenia screening, nutritional and functional assessment, menus including foods with modified and adapted texture, thickeners and oral supplements with adapted texture and rehabilitation treatment programmes. According to the data collected, dysphagia screening, which is currently carried out in three out of four hospitals, and the availability of diagnostic tests (FEES, VFS) can also be improved. In no other pathology, at the hospital level, would extensive screening be considered without having sufficient and adequate material, procedures and personnel to reach an accurate diagnosis.

One of the difficulties we encounter when prescribing a diet for patients with OPD, both during hospital admission and at discharge, is that very often we do not know the degree of dysphagia suffered by the individual, often due to a lack of awareness that exists towards this symptom, because an adequate evaluation is not carried out to determine the severity of the OPD or because there is a lack of instrumental methods that help to classify the degree of severity of the OPD. The objective of the diet of patients with OPD is for them to achieve effective and safe swallowing that allows them, on the one hand, to maintain a good state of nutrition/hydration and, on the other, to avoid respiratory complications and reduce risk situations. Likewise, it is essential to include a training programme for patients and relatives that includes: care and hygiene measures for the oral cavity, safe environmental and postural conditions during meals, preparation of dishes with adequate volume, texture of solids, and viscosity of liquids.

Aware of the great possibilities offered by the training of patients and the widespread use of the Internet, the SEEN has created the Aula Virtual30 [Virtual Classroom] space on its website to promote the training of patients and caregivers. From the Management Committee of the Nutrition Area, and with multidisciplinary teams from Nutrition Units with a long history and experience, informative and training materials have been prepared related to common diseases such as dysphagia, which require knowledge and proper management by the patient and caregiver. The material is available in simple, understandable language and is downloadable. There are also videos related to therapeutic specifications (use of thickeners with different types of liquids) and with testimonials from patients and caregivers. The fundamental objectives are to offer accurate information and teach patients and caregivers the proper and safe management of chronic diseases related to the field of nutrition.

And with regard to hospital discharge, we must also remember the importance of coding and the development of integrated care processes for the follow-up of patients at other levels of care.31,32

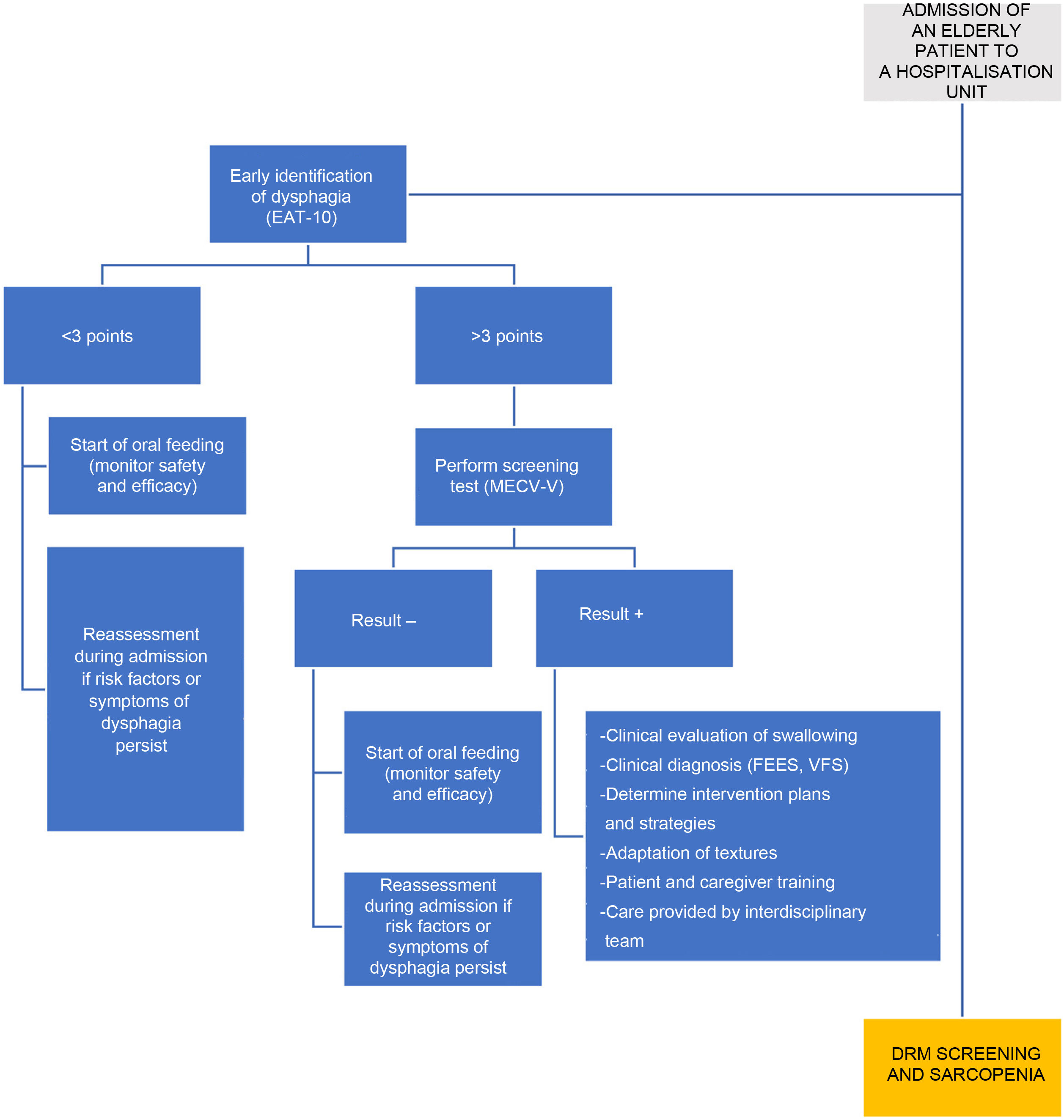

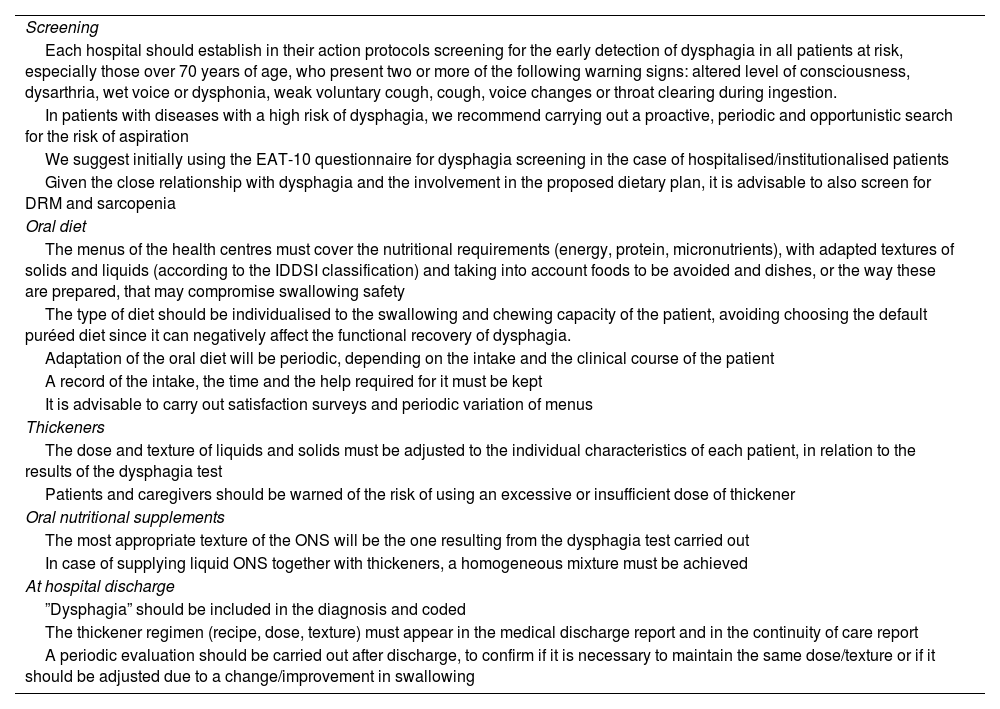

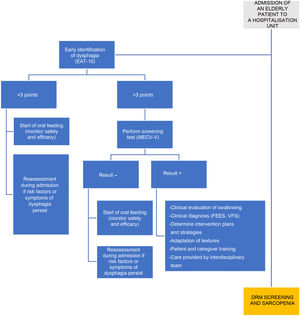

ConclusionsThe situation of the Dysphagia Units at the national level is of concern. It is possible that, from the Nutrition Units and from the other services involved in the management of these patients, we have not been able to convey the need for and importance of correct management of dysphagia that is reported in this document. For this reason, from the Management Committee of the Nutrition Area of the SEEN, we propose a series of general recommendations for routine clinical practice (Table 4) and an algorithm (Fig. 2) that can facilitate both the creation of Dysphagia Units as well as an improvement in the service that those in operation are currently offering. And if the pandemic caused by COVID-19 has served to make this pathology visible, let's take advantage of it to improve the care of all patients who have this difficulty swallowing.

SEEN recommendations for clinical practice in hospitalised patients with dysphagia.

| Screening |

| Each hospital should establish in their action protocols screening for the early detection of dysphagia in all patients at risk, especially those over 70 years of age, who present two or more of the following warning signs: altered level of consciousness, dysarthria, wet voice or dysphonia, weak voluntary cough, cough, voice changes or throat clearing during ingestion. |

| In patients with diseases with a high risk of dysphagia, we recommend carrying out a proactive, periodic and opportunistic search for the risk of aspiration |

| We suggest initially using the EAT-10 questionnaire for dysphagia screening in the case of hospitalised/institutionalised patients |

| Given the close relationship with dysphagia and the involvement in the proposed dietary plan, it is advisable to also screen for DRM and sarcopenia |

| Oral diet |

| The menus of the health centres must cover the nutritional requirements (energy, protein, micronutrients), with adapted textures of solids and liquids (according to the IDDSI classification) and taking into account foods to be avoided and dishes, or the way these are prepared, that may compromise swallowing safety |

| The type of diet should be individualised to the swallowing and chewing capacity of the patient, avoiding choosing the default puréed diet since it can negatively affect the functional recovery of dysphagia. |

| Adaptation of the oral diet will be periodic, depending on the intake and the clinical course of the patient |

| A record of the intake, the time and the help required for it must be kept |

| It is advisable to carry out satisfaction surveys and periodic variation of menus |

| Thickeners |

| The dose and texture of liquids and solids must be adjusted to the individual characteristics of each patient, in relation to the results of the dysphagia test |

| Patients and caregivers should be warned of the risk of using an excessive or insufficient dose of thickener |

| Oral nutritional supplements |

| The most appropriate texture of the ONS will be the one resulting from the dysphagia test carried out |

| In case of supplying liquid ONS together with thickeners, a homogeneous mixture must be achieved |

| At hospital discharge |

| ”Dysphagia” should be included in the diagnosis and coded |

| The thickener regimen (recipe, dose, texture) must appear in the medical discharge report and in the continuity of care report |

| A periodic evaluation should be carried out after discharge, to confirm if it is necessary to maintain the same dose/texture or if it should be adjusted due to a change/improvement in swallowing |

Another area for improvement that scientific societies should encourage is the incorporation of the patient's experience in care processes, in order to improve them, adapting them, as far as possible, to the life circumstances of the people undergoing treatment. The Patient-Reported Experience and Patient-Reported Outcome Measure (PROM) measurement mechanisms help build value in health. This occurs because they integrate care based on quality, by which the differential of an institution is not measured only by the efficacy of the treatment, but by achieving the expectations before, during and after the care. PROMs present questions about the general and functional quality of life of the patient, and of the effect and efficacy of treatment, as well as the need for re-hospitalisation, among others. And analysing and reflecting on the management of dysphagia, assuming what is referred to in the portfolio of services as urgent and on the path of value-based medicine, we cannot forget to include PROMs in hospital records.33

FundingThis study received no specific funding from public, private or non-profit organisations.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest in relation to this study.

We thank the heads of the Endocrinology and Nutrition departments, as well as the members of the Nutrition Area of the SEEN, for their involvement.