The treatment of choice for dyslipidaemia consists of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors, both for patients in primary prevention and for patients in secondary prevention of cardiovascular episodes. Their benefits are based on a drop in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, an increase in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, a decrease in triglyceride levels and inhibition of isoprenoid synthesis. By these mechanisms they manage to stabilise atheromatous plaques, improve endothelial function, decrease the degree of inflammation and reduce the risk of thrombosis.1

However, statins have some side effects, the best known of which affect the muscles and range from muscle pain without elevation of creatine phosphokinase (CPK) levels to rhabdomyolysis, in which CPK levels are very significantly elevated, and also other less common conditions, such as immune-mediated necrotising myopathy (IMNM).2

IMNM is an extremely uncommon complication of statins. The objective of this study was to present a case report of a patient who experienced this problem and to review and update the knowledge of this rare side effect.

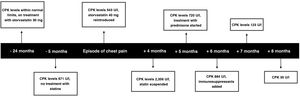

Case reportWe report the case of 68-year-old man with a history of hypertension, carotid atheromatosis and dyslipidaemia, on treatment with acetylsalicylic acid 100 mg, valsartan 80 mg and rosuvastatin 20 mg. Concerning his family history, notably, his mother and sister had been diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis. The patient was referred to the Endocrinology and Nutrition Department due to an increase in CPK levels. A review of his medical history revealed that he had been on treatment for two years with atorvastatin 30 mg with normal CPK levels, had stopped treatment and had undergone laboratory testing at five months that showed CPK levels of 671 U/l (1–190 U/l). Subsequently, he was admitted to Cardiology for atypical chest pain. Initial laboratory testing revealed ultrasensitive troponin levels of 24.4 pg/mL (<14 pg/mL) and CPK levels of 543 U/l. During admission, he underwent a stress test and cardiac catheterisation, which yielded no findings. Despite this, rosuvastatin 20 mg was restarted as the patient's low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels were 159 mg/dl. After the lipid-lowering agent was started, progressive elevation of CPK levels persisted; for this reason, he was referred to our practice. In the first visit, rosuvastatin was suspended, ezetimibe 10 mg was started and Neurology was consulted.

His Neurology assessment revealed mild muscle pain and a certain degree of weakness in the shoulder girdle. His CPK levels continued to rise even though statins had been suspended (Fig. 1). Magnetic resonance imaging showed diffuse areas of short tau inversion recovery (STIR) signal hyperintensity consistent with foci of inflammatory myopathy. Full-body computed tomography yielded no pathological findings. A biopsy of the right tibialis anterior muscle revealed regenerative fibres and fibres with a necrotic appearance; these changes were consistent with immune-mediated necrotising inflammatory myopathy. The patient's serum tested positive for anti-HMGCR antibodies, which act against HMG-CoA reductase. Treatment was started with prednisone at a dose of 1 mg/kg/day; subsequently, mycophenolate mofetil 500 mg every 12 h was added, and the patient's CPK levels improved to 35 U/l. To manage his dyslipidaemia, treatment was started with alirocumab 75 mg every two weeks, which achieved good management.

The incidence of IMNM is estimated at two to three cases per 100,000 exposed patients,2 unlike muscle pain caused by statin use, which is a much more common and difficult-to-measure side effect that potentially affects 2%–20% of patients on treatment with them. A review of 100 patients with IMNM found that unlike statin-induced rhabdomyolysis which took place at the start of treatment, patients with IMNM were on treatment with statins for an average of 40 months before developing signs and symptoms.3,4 Clinically, it manifests as progressive weakness of the proximal muscles that does not improve despite suspension of statins. This allows this condition to be distinguished from other types of statin-induced myopathy in which improvement does occur after statins are suspended. In rare cases, it can cause dysphagia, joint pain or Raynaud's phenomena.5 Laboratory testing shows elevated CPK levels.2,6 Other causes of IMNM may be autoimmune diseases of connective tissue, viral infections and paraneoplastic syndromes.7

The pathophysiology of this condition has not yet been entirely elucidated. Currently, muscle damage is thought to be caused by anti-HMGCR antibodies, which act against the HMG-CoA reductase present in muscle cells; this enzyme is more abundant in muscle cells following statin use. A higher incidence of the human leukocyte antigen DRB1*11:01 allele has been reported in patients with positive anti-HMGCR antibodies; this could carry a certain genetic susceptibility to this condition.2,4,6

The following should be performed for a definitive diagnosis: serology to detect anti-HMGCR antibodies, which aid in distinguishing this condition from other causes of autoimmune necrotising myopathy,6 and a muscle biopsy, which normally shows necrosis with regeneration of muscle fibres and little associated inflammation.8,9

Current treatment of IMNM is based on immunosuppression and suspension of treatment with statins. Treatment with high-dose corticosteroids can be started, and other immunosuppressants (mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine or methotrexate) can be subsequently added; no differences in efficacy between these drugs have been observed. The use of rituximab or immunoglobulins has been reported in cases refractory to initial treatment.2,3 When monitoring treatment response, it is important to record the clinical improvement reported by the patient or use a test such as dynamometry to measure improvement in muscle strength.8 In addition, CPK levels can be used as a marker of disease activity, although it must be borne in mind that some patients may continue to show elevated CPK levels despite clinical improvement.6