This research has not received specific funding from public sector agencies, the commercial sector or non-profit organisations.

The patient received and signed an informed consent form for the surgical procedure and for the use of her data and images for teaching and scientific purposes.

The incidence of epidermoid tumours is around 1–2% of all intracranial tumours, of which 10% are extradural, generally in the diploic space.1 The most common locations are the cerebellopontine angle and the parasellar region, and less commonly, the sylvian fissure, suprasellar region and cerebral ventricles. They are not often found along the midline and a pure intrasellar location is even more rare, with only seven cases published in the literature.2–7 Most cases that affect the sellar region are due to extension of the lesion from the surrounding subarachnoid or basal cisterns.8,9 They are most common in young adults, with the majority being diagnosed between the ages of 20 and 50. Although not an inherently neoplastic lesion, cases that progress to malignancy have been reported.8

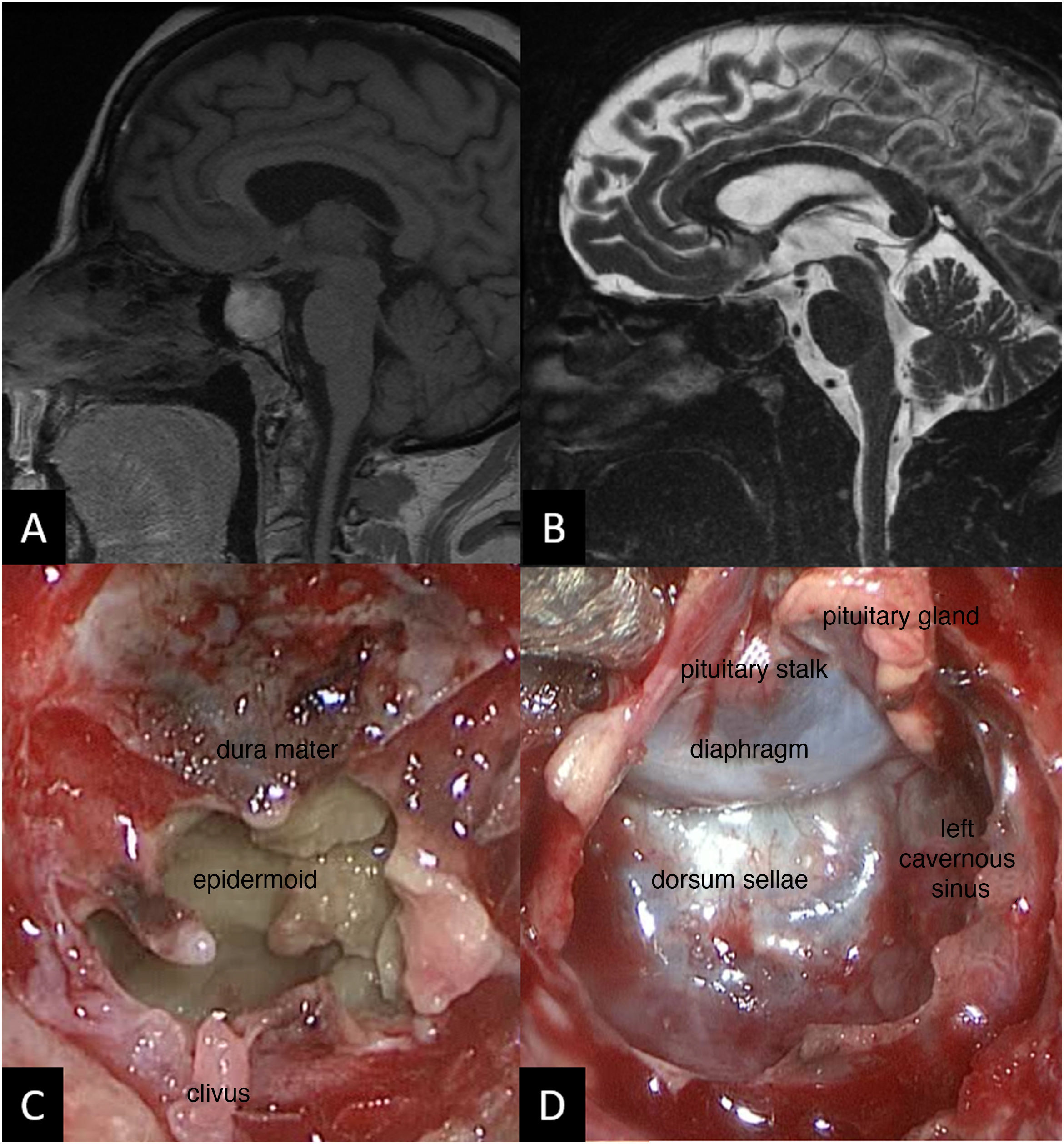

We present the case of a 65-year-old woman diagnosed with primary autoimmune hypothyroidism and referred to endocrinology due to a six-month history of poor hypothyroidism control, asthenia, weight loss, frequent vomiting and abdominal discomfort. The patient did not report polyuria or polydipsia. Four years prior, she had received a cranial CT scan in which an empty sella turcica was observed. Because of the symptoms she exhibited, her ACTH, cortisol, prolactin, GH, IGF-1, LH and FSH levels were tested, leading to a diagnosis of secondary adrenal insufficiency, hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and adult GH deficiency. An MRI of the pituitary gland was performed, and the images can be seen in Figs. 1A and B.

A) MRI T1 sequence. Well-delimited 2-cm intrasellar mass of insufflated appearance, heterogeneously hyperintense in T1, with nodular gadolinium uptake in dynamic sequences in the anterosuperior third of the lesion. B) MRI T2 sequence. The lesion is hypointense, does not compress the optic tract and extends the sella turcica, occupying part of the sphenoid sinus. C) Intra-operative image showing the squamous appearance of the tumour, with little vascularisation and a slight yellowish colour due to its keratin content. D) Intra-operative image after resection showing the sellar floor and dorsum sellae and the walls of both cavernous sinuses, now free of tumour. Above this can be seen the intact diaphragm and the remainder of the compressed pituitary gland and pituitary stalk in the upper left.

The patient was operated on using an endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal approach with full excision of the lesion, which was formed of yellowish-white squamae (Figs. 1C and D). The pathological diagnosis was of anucleate laminar keratin fragments intermixed with fragments of fibrous tissue consistent with an epidermoid cyst. The post-operative period was free of complications, with the pre-existing hormonal deficiencies persisting and no new alterations. It is now five years later and the patient maintains the same hormonal deficiencies, while no recurrence of the lesion can be seen on MRI.

In addition to the exceptional nature of the pathological diagnosis, so too is the patient's age, as these are usually diagnosed in younger patients. Epidermoid cysts are congenital tumours that grow very slowly, at a similar rate to epidermal skin cells. This growth is due to the deposition of desquamated epithelial cells, which leads to the accumulation of keratin and cholesterol within the cyst; this often occurs via the subarachnoid space.5 They have a thin external epithelial capsule and pearly-white or yellowish-white contents with cheese-like squamae, and can become cystic through abscessification of the cyst or liquefaction of the keratin as the mass grows. They are differentiated from dermoid cysts in that the latter often have a thicker capsule, tend to be located on the midline and their interior contains epidermal and dermal elements.6

The origin of this type of tumour is attributed to an incomplete or anomalous separation of the neuroectoderm between the third and fifth week of gestation, with ectodermal elements persisting upon closure of the neural groove. It is also possible for these cysts to form after a traumatic or iatrogenic implantation of epidermis in the subarachnoid space. In addition, in cases with sellar location, the hypotheses for formation are the proliferation of squamous cell foci in the anterior pituitary and the possible metaplasia of anterior pituitary cells.6

The symptoms are caused by local compression, and are often very insidious due to the slow growth. In our case, they consisted solely of anterior pituitary hormonal deficiencies due to compression of the pituitary, although curiously, and unlike that published by other authors, with preserved neurohypophyseal function, and with no invasion of the diaphragma sellae and therefore no subarachnoid dissemination. In contrast, most epidermoid cysts invade the subarachnoid space, encircling cranial arteries and nerves and therefore often beginning with neurological symptoms.1 We found some cases in the literature of sudden worsening due to stroke or rupture of the cyst causing aseptic meningitis,5 although most commonly at the sellar level they cause symptoms of hypopituitarism.7

CT imaging often shows a hypodense lesion, almost identical to CSF. In our case, the patient had a CT diagnosis of empty sella turcica. Given the diversity of their content (water, keratin, cholesterol), the signal observed on MRI is very variable, which at times makes preoperative diagnosis very difficult.7,10 Half are hyperintense in the T2 sequence, and they are usually hypointense in T1.10 Curiously, in our case the signal is the opposite to that most commonly published, which may be due to a greater protein and/or fat component, or the presence of subacute intralesional bleeding, something that has been published previously.5

They are not accompanied by oedema and can be calcified in 10–25% of cases.1 The borders are often irregular and there may be slight gadolinium uptake in the capsule.8 The most defining radiological characteristic is Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequence hyperintensity,4 as well as hyperintensity in diffusion sequences (restricted diffusion)11; in our case, none of these was performed since they are not included in the routine pituitary protocol and this diagnosis was not suspected. The differential diagnosis must be made with reference to arachnoid cyst, Rathke’s cleft cyst, craniopharyngioma and even adenoma.10

The treatment is surgicalideally, resection of the cyst including the capsule, but depending on the location this may not be advisable due to the risk of injury to the vasculature and cranial nerves when the cyst is in the subarachnoid space.1

Recurrence of the lesion is observed in 1–54% of cases.8,9 Although some studies show similar rates of progression for complete and subtotal resections,9 complete resection is often curative. Complete resection will therefore be performed provided that the risk of injury to the adjacent structures is low.9

Please cite this article as: Pérez López C, Parra P, Martín Rojas-Marcos P, Campos Mena S, Álvarez-Escolá C. Quiste epidermoide intraselar. A propósito de un caso. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2022;69:227–229.