Metabolic syndrome (MS) is becoming one of the main public health problems of the 21st century.1 Its pathogenesis is complex, with many uncertainties remaining.

MS is defined as a series of risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), cardiovascular disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and obstructive sleep apnea, characterized by insulin resistance and compensating hyperinsulinism associated with carbohydrate and lipid metabolic disorders, high blood pressure (HBP) and obesity.2,3

A cross-sectional, observational, analytical study with probabilistic, stratified, and randomized sampling is reported here. Confidence level: 95% and error: 5%. The study objective was to assess the prevalence of MS in the population over 18 years of age (n=4836) in the municipality of San Ignacio, Francisco Morazán, Honduras, within the context of a primary care public health strategy initiative involving 16 of its communities, from September to December 2015, with a global population of 8831 inhabitants. The study protocol was evaluated and approved by the bioethics committee of the scientific research unit (registry no. 00003070).

The inclusion criteria were: permanent residents in the municipality over 18 years of age who gave their informed consent to participate in the study. Pregnant women, patients with disabling diseases or cognitive impairment, temporary residents who would therefore be unavailable for assessment and follow-up, and subjects who did not give their written informed consent were excluded from the study.

The study was divided into two phases. A first phase was designed to identify the risk factors using a screening protocol validated by the School of Medical Sciences of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Honduras, which evaluated the sociodemographic variables collected in a personal interview: age, sex, race, educational level, occupation, community of residence, and socioeconomic level. The clinical data recorded included prior diagnosis and/or any family history of T2DM and HBP, alcohol and/or tobacco consumption, and the measurement of the abdominal circumference (AC) as an anthropometric variable. A total of 2525 inhabitants meeting the inclusion criteria were interviewed (males: 791, females: 1734). Of these, 1380 (males: 377, females: 1003) met the defined risk criteria (score≥5) and were subsequently evaluated in the second phase of the study, consisting of a clinical/anthropometric evaluation: weight, height, the body mass index (BMI), blood pressure (BP), and the collection of a blood sample for biochemical tests (fasting blood glucose, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol (HDL-C), and triglycerides).

The sample size was calculated using Netquest® (http://www.netquest.com/es/panel/calidad-iso26362.html), with a confidence level of 95% and an error of 5%. The resulting required sample size was n=301, and the final sample consisted of 342 individuals. The initially selected subjects were not replaced.

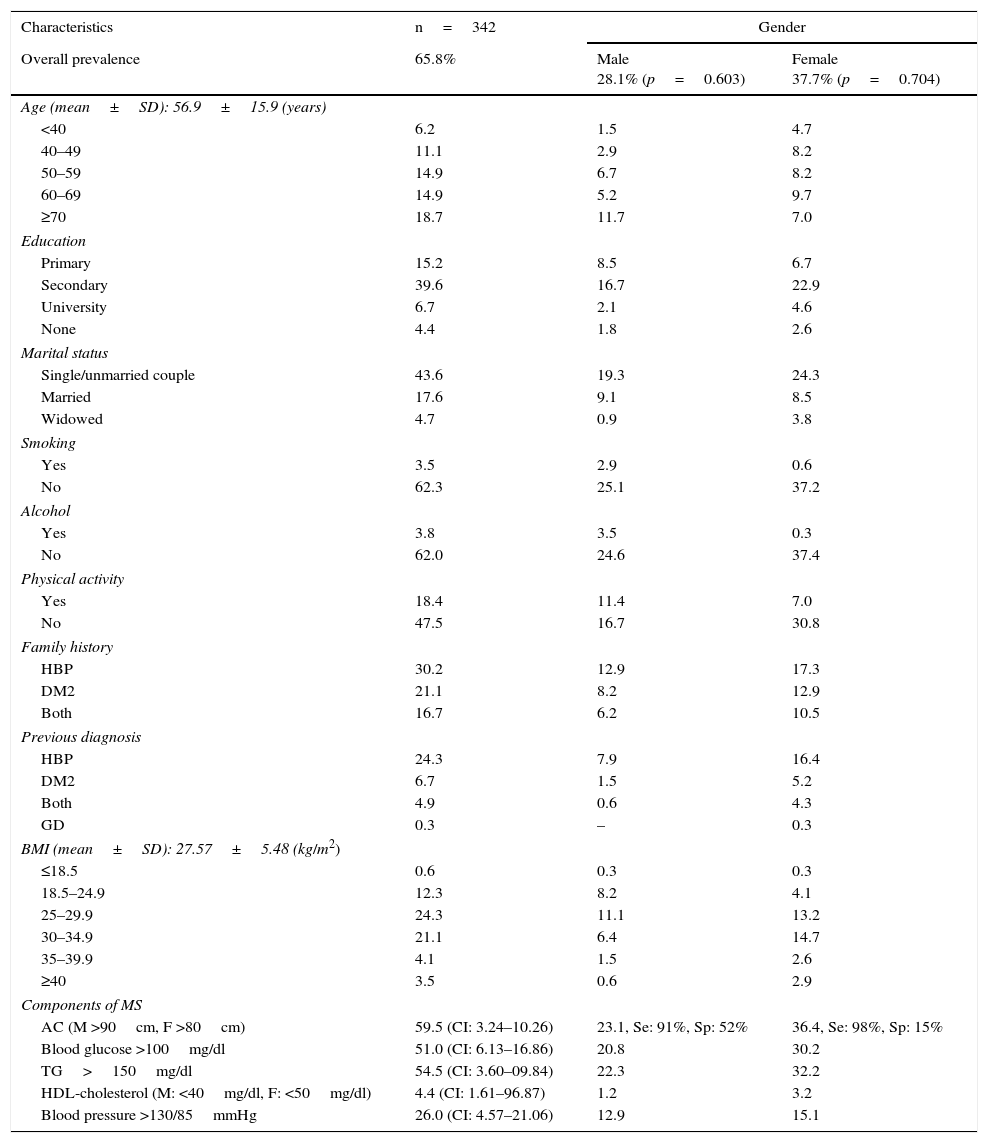

The prevalence of MS was determined based on the criteria of the National Cholesterol Education Program–Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP-ATPIII),4 and was found to be 65.8%. The principal study data are summarized in Table 1.

Prevalence of metabolic syndrome (MS) adjusted to its main risk factors and sociodemographic characteristics in relation to gender; community-based PHC, Honduras, 2015.

| Characteristics | n=342 | Gender | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall prevalence | 65.8% | Male 28.1% (p=0.603) | Female 37.7% (p=0.704) |

| Age (mean±SD): 56.9±15.9 (years) | |||

| <40 | 6.2 | 1.5 | 4.7 |

| 40–49 | 11.1 | 2.9 | 8.2 |

| 50–59 | 14.9 | 6.7 | 8.2 |

| 60–69 | 14.9 | 5.2 | 9.7 |

| ≥70 | 18.7 | 11.7 | 7.0 |

| Education | |||

| Primary | 15.2 | 8.5 | 6.7 |

| Secondary | 39.6 | 16.7 | 22.9 |

| University | 6.7 | 2.1 | 4.6 |

| None | 4.4 | 1.8 | 2.6 |

| Marital status | |||

| Single/unmarried couple | 43.6 | 19.3 | 24.3 |

| Married | 17.6 | 9.1 | 8.5 |

| Widowed | 4.7 | 0.9 | 3.8 |

| Smoking | |||

| Yes | 3.5 | 2.9 | 0.6 |

| No | 62.3 | 25.1 | 37.2 |

| Alcohol | |||

| Yes | 3.8 | 3.5 | 0.3 |

| No | 62.0 | 24.6 | 37.4 |

| Physical activity | |||

| Yes | 18.4 | 11.4 | 7.0 |

| No | 47.5 | 16.7 | 30.8 |

| Family history | |||

| HBP | 30.2 | 12.9 | 17.3 |

| DM2 | 21.1 | 8.2 | 12.9 |

| Both | 16.7 | 6.2 | 10.5 |

| Previous diagnosis | |||

| HBP | 24.3 | 7.9 | 16.4 |

| DM2 | 6.7 | 1.5 | 5.2 |

| Both | 4.9 | 0.6 | 4.3 |

| GD | 0.3 | – | 0.3 |

| BMI (mean±SD): 27.57±5.48 (kg/m2) | |||

| ≤18.5 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 12.3 | 8.2 | 4.1 |

| 25–29.9 | 24.3 | 11.1 | 13.2 |

| 30–34.9 | 21.1 | 6.4 | 14.7 |

| 35–39.9 | 4.1 | 1.5 | 2.6 |

| ≥40 | 3.5 | 0.6 | 2.9 |

| Components of MS | |||

| AC (M >90cm, F >80cm) | 59.5 (CI: 3.24–10.26) | 23.1, Se: 91%, Sp: 52% | 36.4, Se: 98%, Sp: 15% |

| Blood glucose >100mg/dl | 51.0 (CI: 6.13–16.86) | 20.8 | 30.2 |

| TG>150mg/dl | 54.5 (CI: 3.60–09.84) | 22.3 | 32.2 |

| HDL-cholesterol (M: <40mg/dl, F: <50mg/dl) | 4.4 (CI: 1.61–96.87) | 1.2 | 3.2 |

| Blood pressure >130/85mmHg | 26.0 (CI: 4.57–21.06) | 12.9 | 15.1 |

PHC: primary health care; SD: standard deviation; GD: gestational diabetes; T2DM: type 2 diabetes mellitus; Sp: specificity; HBP: high blood pressure; BMI: body mass index; AC: abdominal circumference; Se: sensitivity; MS: metabolic syndrome; TG: triglycerides; % (95% confidence interval).

In a cross-sectional, population-based study, Wong-McClure et al. reported a high general prevalence of MS in Central America, with a higher prevalence in Honduras (21.1%; CI: 16.4–25.9) than in all the other countries in the region. These authors also found the prevalence to be notably greater among females than in males in all 5 of the studied countries.5 This increased prevalence of MS in women has not been observed in studies of MS in developed countries, where the prevalence is reportedly very similar in both sexes or higher among the male population.6 Nevertheless, previous studies have described a greater prevalence of MS in women in Latin America.7

Villamor et al.8 found the prevalence of MS to be positively correlated to age, regardless of gender. They also described an inverse correlation to female educational level and a positive correlation to household food security and height among males. The metabolic risk factor burden was disproportionally greater in women of a lower socioeconomic status and in males of a higher socioeconomic status.

A significant aspect of both studies is that they were conducted in the main cities of the respective countries, in which the sociodemographic, economic, and nutritional variables are relatively different from those found in our study. In effect, our study was conducted in an area not subject to the constant effects of globalization, and still essentially characterized by agriculture and cattle raising.

Latin American women have experienced one of the greatest annual increases in obesity rates between 1990 and 2010: 11.4% and 6.2% in the rural and urban settings, respectively.9 These increases are not homogeneous within the region. In this study, 78.9% (males: 37%, females: 41.9%) presented an AC consistent with the respective mean (±standard deviation) (96.86±11.44cm).

However, when patients with and without MS were compared in relation to sex, there were no significant differences (p=0.1657). Nevertheless, a sedentary lifestyle and obesity in women were positively associated with the risk of MS.

A multivariate analysis revealed an association between MS and AC>80cm in women and >90cm in men (odds ratio [OR]: 5.7; 95% CI: 3.2–10.2), BMI>25kg/m2 (OR: 3.5; 95% CI: 2.2–5.8), fasting blood glucose>100mg/dl (OR: 10.4; 95% CI: 6.1–16.8), triglycerides>150mg/dl (OR: 5.9; 95% CI: 3.6–9.8), and total cholesterol >200mg/dl (OR: 2.24; 95% CI: 3.7–1.4).

In conclusion, it can be stated that MS is a genuine public health problem, and that early identification of the affected population is essential, since the syndrome is associated with diseases that lead to a very high mortality rate worldwide. MS is a public health problem that may be fully dealt with in primary care, as the diagnosis poses no major difficulties.

FundingOwn funding.

Material donation by SUMILAB, S.A.

Conflicts of interestThe authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Escober Torres J, Valeriano Sabillón K, Osorto Lagos E, Argueta Cabrera EG, Carmenate Milián L. Síndrome metabólico: primer estudio de prevalencia en atención primaria, Honduras. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2017;64:273–276.