Quality of life and morbidity–mortality in acromegaly are related to biochemical control (IGF-1 normal for the age and sex of the patient).1 First line treatment includes trans-sphenoidal surgery and/or first generation somatostatin analogs (SSAs) that mainly act through isoform 2 of the somatostatin receptor (SSR). Epidemiological studies and large national registries2–5 indicate that this strategy is not able to secure a remission rate of more than 50%. Second line treatment includes pegvisomant as monotherapy or combined with SSAs, which improves percentage remission but involves greater therapeutic complexity.

The pivotal studies on pasireotide,6,7 an SSA with affinity for various SSRs, in particular SSR5, have revealed superior performance versus the first generation SSAs, thereby making it possible to control a larger number of cases. In our routine practice, acromegalic patients poorly controlled with SSAs are mostly treated with pegvisomant as monotherapy or combined with SSAs. There are practically no data on the usefulness of pasireotide in clinical practice.

We present four acromegalic patients with deficient control following surgery and SSAs and/or pegvisomant in which pasireotide allowed for control of IGF-1 concentrations and the size of the remnant tumor tissue.

Case 1A 53-year-old woman presented with diabetes mellitus adequately controlled with oral antidiabetic drugs and acromegaly secondary to a hypophyseal macroadenoma (isointense in T2-weighted imaging) measuring 2.5cm in size, with invasion of the right cavernous sinus and suprasellar cistern, GH 6.9ng/ml, and IGF-1 1028ng/ml (upper limit of normal [ULN] for age and sex 253ng/dl).

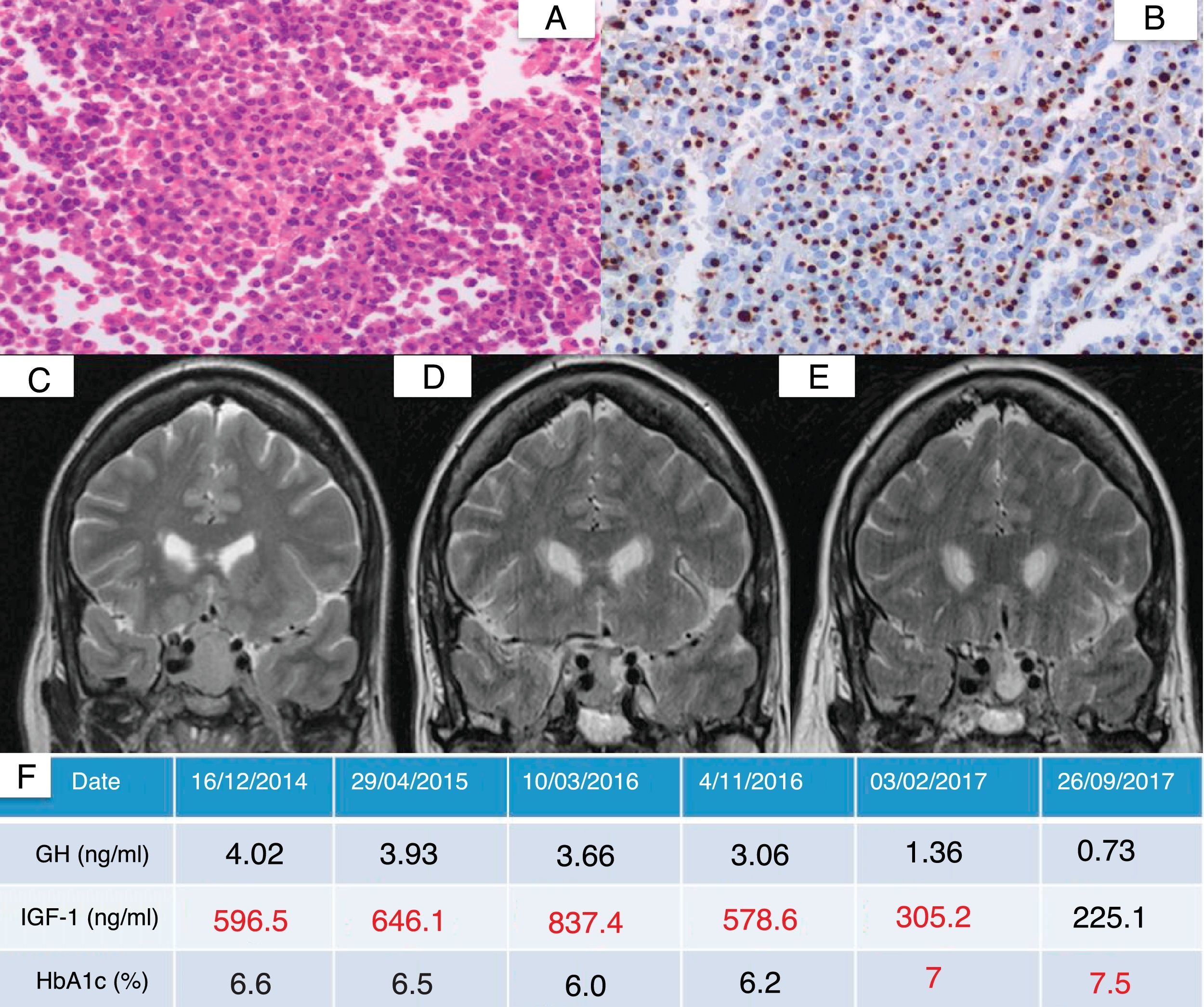

Endoscopic trans-sphenoidal resection proved incomplete. This was a scantly granular adenoma with intense GH expression. Following surgery, the patient required SSA treatment at maximum doses, with the posterior addition of pegvisomant at doses of up to 30mg/day, without achieving control of IGF-1 due to poor tolerance of the latter drug (muscle pain). The patient was re-operated upon and irradiated in early 2016, after which the tumor size remained stable (15mm×13mm), though with persistent IGF-1 elevation (578.6ng/dl), with good glycemic control (HbA1c 6.2%). Pasireotide was started in late 2016 at a dose of 40mg/month, followed by a 45% reduction in maximum tumor diameter after three months of treatment. A slight worsening of glycemic control was observed as an adverse effect. Fig. 1 shows the pathology findings and the radiological and biological evolution.

Histopathological findings and radiological and biochemical evolution of a patient with acromegaly (case 1) after starting pasireotide. (A) Hypophyseal parenchyma showing structural alteration and a homogeneous proliferation of medium size polygonal shaped cells with round nuclei and an eosinophilic cytoplasm (hematoxylin–eosin [HE], 400×). (B) Paranuclear dot expression of cytokeratin CAM5.2, consistent with a scantly granular pattern (CAM5.2, 400×). (C) Presurgical hypophyseal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan showing a 2.5cm adenoma (isointense in T2-weighted imaging). (D) MRI scan prior to the introduction of pasireotide. (E) Hypophyseal MRI scan after three months of treatment with pasireotide. (F) Evolution of GH, IGF-1 and HbA1c. IGF-1 value adjusted for age and sex: 93–253ng/ml.

A 25-year-old male presented with a hypophyseal macroadenoma measuring 3.2cm in size, with invasion of the right cavernous sinus (hypointense in T2-weighted imaging). Endoscopic trans-sphenoidal surgery was carried out. This was a scantly granular adenoma with intense GH expression. Tumor tissue measuring 8mm×11mm remained in the right cavernous sinus. The patient received SSA treatment at maximum doses, with the combination of cabergoline (1.5mg/week) and pegvisomant 35mg/day, though without achieving adequate biochemical control (IGF-1 of about 1.5–1.6 ULN). Cabergoline and SSA were suspended in late 2016, and pasireotide was started at a dose of 40mg/month. Biochemical control was achieved three months later (IGF-1 279.7ng/ml).

Case 3A 35-year-old woman presented with an invasive macroadenoma measuring 2.4cm in size (hyperintense in T2-weighted imaging). Endoscopic trans-sphenoidal resection proved incomplete, with remnant tumor tissue in the left cavernous sinus. The pathology study revealed a scantly granular adenoma with intense GH immune reactivity. Resistance to SSA was observed; we therefore switched to pegvisomant 20mg/day, with optimum biochemical control over the following 8 years. However, in 2016 we confirmed that the remnant tumor tissue had grown in the previous three years from 16mm×12mm×11mm to 20mm×13mm×13mm in size. We therefore replaced pegvisomant with pasireotide 40mg/month, combined with radiotherapy. After three months (45 days after radiotherapy), the remnant tumor was seen to have decreased over 50% in size (10mm×9mm×7mm), with the normalization of IGF-1.

Case 4A 76-year-old woman had been diagnosed 20 years previously with a hypophyseal macroadenoma measuring 2cm in size (hyperintense in T2-weighted imaging). Incomplete surgical resection was performed, with the addition of SSA and adjuvant radiotherapy due to resistance to the drug. A review of the pathology study revealed a scantly granular tumor. She continued with SSA as antiproliferative therapy, with slightly elevated IGF-1 levels (1.3–1.4 ULN). After fifteen years the IGF-1 levels were seen to have increased (1.6 ULN), with no significant changes in the remnant tumor (16mm×18mm×13mm). The patient was subsequently enrolled in the PAOLA trial in 20117 (pasireotide 40mg/month). Since then the IGF-1 levels have remained normal and the tumor has decreased 35% in maximum diameter.

We have described four acromegalic patients with aggressive hypophyseal tumors (three having been irradiated) which did not achieve adequate biochemical control after surgery and SSA.

All of them were successfully treated with LAR (long-acting release) pasireotide. The treatment indication was a consequence of the inefficacy of pegvisomant as monotherapy or combined with SSA, due either to pegvisomant intolerance or to tumor growth. The IGF-1 levels were normalized in all four cases, and the tumor volume decreased in three patients. It is difficult to quantify the influence of radiotherapy in case 1 (performed 10 months previously), and it possibly did not prove significant in the other two cases (20 years and 45 days before radiological control). With the exception of worsened glycemic control in one case, no other adverse effects were recorded.

The above described resistance to first line treatment could have been anticipated. Invasion of the cavernous sinus is known to complicate complete tumor removal. Also, hyperintensity in T2-weighted imaging and a scantly granular histological pattern are predictive of resistance to first line treatment with SSAs.8 Our four patients presented at least two of these three factors. The availability of data referring to SSR5 expression would have been very useful for the choice of pasireotide in first line treatment. The current acromegaly treatment guides propose advancing to the next line of treatment after failure of the previous line has been confirmed. We believe that the choice of medical treatment should be based on the prediction of therapeutic success. In this regard, the adoption of a personalized medicine and the abandonment of the classical trial-and-error strategy have already been contemplated.9,10

In a small number of cases we have been able to provide evidence of the efficacy of pasireotide as an alternative in patients that fail to respond to first line treatment with SSAs. Such failure could have been anticipated if the characteristics of these tumors had been taken into account, and years of treatment inefficacy along with the added costs could consequently have been avoided.

Please cite this article as: Biagetti B, Obiols G, Martinez Saez E, Cordero E, Mesa J. Pasireótida en acromegalia por tumores agresivos, descripción de 4 casos. Hacia una medicina personalizada. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2018;65:130–132.

![Histopathological findings and radiological and biochemical evolution of a patient with acromegaly (case 1) after starting pasireotide. (A) Hypophyseal parenchyma showing structural alteration and a homogeneous proliferation of medium size polygonal shaped cells with round nuclei and an eosinophilic cytoplasm (hematoxylin–eosin [HE], 400×). (B) Paranuclear dot expression of cytokeratin CAM5.2, consistent with a scantly granular pattern (CAM5.2, 400×). (C) Presurgical hypophyseal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan showing a 2.5cm adenoma (isointense in T2-weighted imaging). (D) MRI scan prior to the introduction of pasireotide. (E) Hypophyseal MRI scan after three months of treatment with pasireotide. (F) Evolution of GH, IGF-1 and HbA1c. IGF-1 value adjusted for age and sex: 93–253ng/ml. Histopathological findings and radiological and biochemical evolution of a patient with acromegaly (case 1) after starting pasireotide. (A) Hypophyseal parenchyma showing structural alteration and a homogeneous proliferation of medium size polygonal shaped cells with round nuclei and an eosinophilic cytoplasm (hematoxylin–eosin [HE], 400×). (B) Paranuclear dot expression of cytokeratin CAM5.2, consistent with a scantly granular pattern (CAM5.2, 400×). (C) Presurgical hypophyseal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan showing a 2.5cm adenoma (isointense in T2-weighted imaging). (D) MRI scan prior to the introduction of pasireotide. (E) Hypophyseal MRI scan after three months of treatment with pasireotide. (F) Evolution of GH, IGF-1 and HbA1c. IGF-1 value adjusted for age and sex: 93–253ng/ml.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/25300180/0000006500000002/v1_201803230448/S2530018018300222/v1_201803230448/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr1.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)