Gestational diabetes (GD) is diabetes first diagnosed during the second or third trimester of pregnancy not clearly due to the presence of pre-existing diabetes.1 The prevalence of GD varies widely depending on diagnostic criteria, ethnicity and prevalence of type 2 diabetes in the population.2,3 There is currently no consensus among scientific associations regarding the diagnostic criteria for GD, meaning that different strategies coexist: (1) a one-step strategy, as proposed by the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups; and (2) a two-step strategy with cut-off points from the National Diabetes Data Group (NDDG) or from Carpenter and Coustan. Regardless of the strategy used, the diagnosis of GD has significant repercussions for mothers and their newborns.4 A multicentre study conducted in Spain on the possible impact of applying the Carpenter and Coustan criteria confirmed the high prevalence of GD according to the "classic" NDDG criteria, which would further increase with the application of the Carpenter and Coustan criteria.5 Application of the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups criteria in our setting would further increase the prevalence of GD, but could be associated with better pregnancy outcomes and ultimately a reduction in direct costs.6–8 For this reason, according to the recommendations of the Grupo Español de Diabetes y Embarazo [Spanish Diabetes and Pregnancy Group],9 our centre uses a two-step strategy with NDDG cut-off points.

The working hypothesis was that, in our setting, the complexity of the (two-step) method and the established (NDDG) cut-off points could reduce the prevalence of GD compared to the expected prevalence despite the significant resources required to implement it. For this reason, we designed a non-interventional observational study as part of an undergraduate thesis with the authorisation of the independent ethics committee for research involving medicinal products at our centre. It was estimated that a random sample of 1,822 individuals would be sufficient to estimate, with a 95% confidence interval (CI) and a precision of ±1 percentage unit, a prevalence in the population that could be anticipated to be around 5%, according to prevalence data from a study by Behboudi-Gandevani et al.3 using the same diagnostic method.

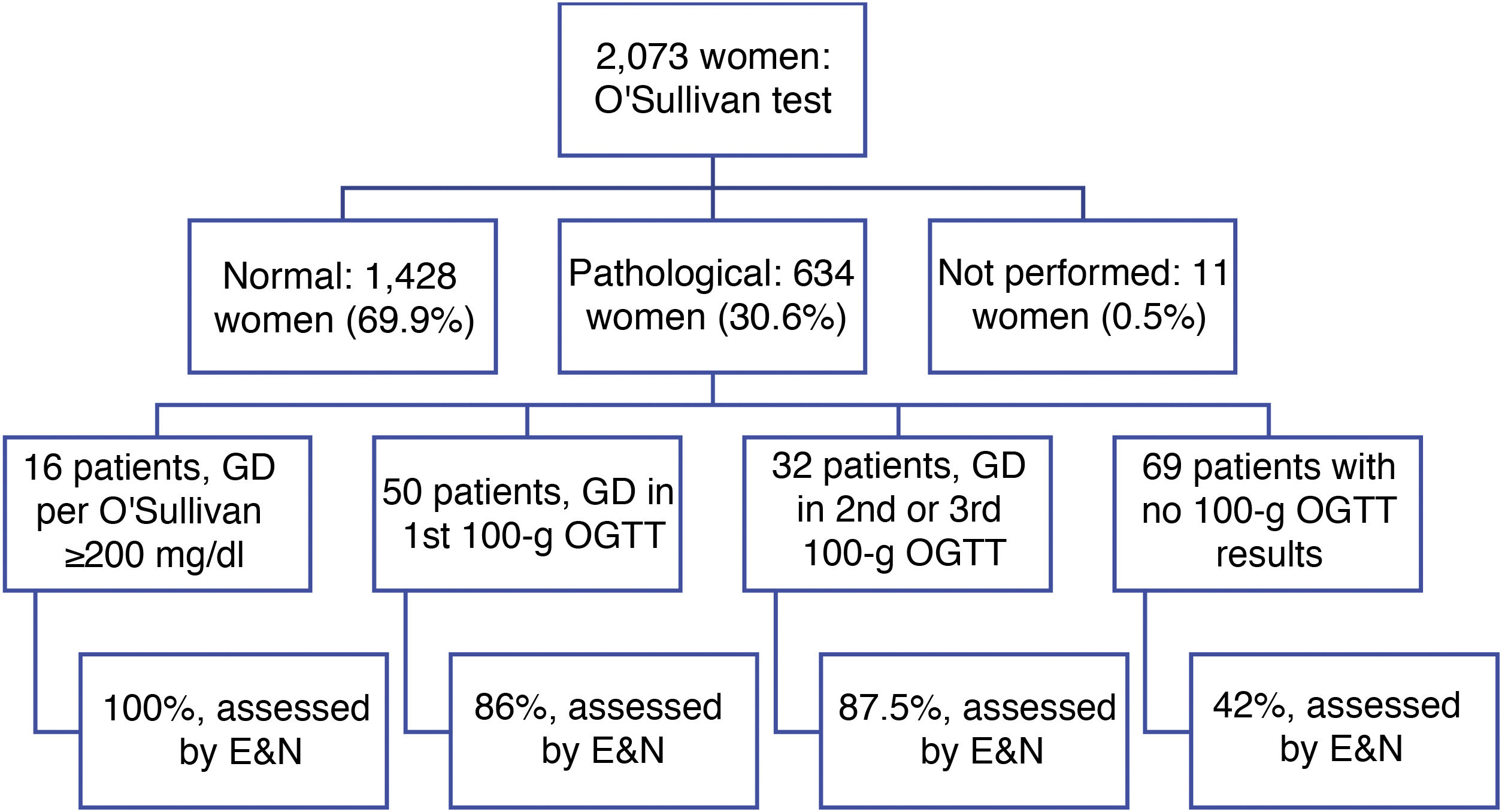

Outcomes in 2,073 women 18–45 years of age, inclusive, who underwent the O'Sullivan test between 1 January 2018 and 31 December 2018 were analysed (Fig. 1). The mean age was 32.4 years (SD 5.6); the mean 1-h glucose level in the O'Sullivan test was 124.9 mg/dl (SD 31.6), with the p95 value corresponding to 180 mg/dl. The O'Sullivan test was normal in 1,428 patients (68.9%), pathological in 634 patients (30.6%) and unavailable in 11 patients (0.5%). Next, the 100-g oral glucose tolerance testing (OGTT) results for the 634 patients with pathological O'Sullivan results were reviewed. A total of 98 patients, equivalent to 4.7% (95% CI 3.9–5.7), were diagnosed with GD (p = 0.5724 compared to the expected value of 5%). Of them, 16 patients (16.3%) were diagnosed directly with the screening test, as they had an O'Sullivan test value greater than or equal to 200 mg/dl; 24 patients (24.5%) required two confirmatory tests and eight patients (8.2%) required three confirmatory tests to be diagnosed with GD. Therefore, just 50 patients (51%) were diagnosed with GD by performing a screening test and a single confirmatory test. In addition, 69 patients with a positive screening test (10.9% of them) lacked 100-g OGTT results.

Of the 98 patients diagnosed with GD, 100% of the patients diagnosed directly in a screening test were assessed by endocrinology and nutrition, as were 86% of those diagnosed in the first confirmatory test and 87.5% of those diagnosed in the second or third confirmatory test. Of them, 66.7% were treated with diet, 18.4% with rapid-acting insulin analogues, 13.8% with a complete (basal and postprandial) insulin regimen and 1.15% (one patient) with basal insulin. Of the 69 patients with a positive screening test who lacked 100-g OGTT results, just 42% had been assessed by endocrinology and nutrition.

Thus, our results highlight the great difficulty of diagnosing GD using the two-step method with NDDG cut-off points. Of the 2,073 women evaluated with the O'Sullivan test, just 98 were diagnosed with GD, accounting for 4.7% (95% CI, 3.9–5.7) of the total. This value is consistent with the reference 5% from the study by Behboudi-Gandevani et al., but lower (p < 0.05) than the 8.8% obtained in a study by Ricart et al. One possible reason for this lower prevalence of GD could be the characteristics of our sample, as it seems that the baseline glucose levels of our population were lower than the population included in prior studies.7 The second difficulty seen in our study was linked to the low percentage of patients diagnosed by performing a screening test and a single 100-g OGTT as a confirmatory test (32.7% of patients with GD required two or three confirmatory tests during pregnancy and 16.3% had been directly diagnosed in the screening test), and the high percentage of patients with a positive screening test who lacked 100-g OGTT results.

In conclusion, the NDDG-based diagnostic criteria, used in our setting, were associated with a low prevalence of GD (4.7% [95% CI, 3.9–5.7]), high diagnostic complexity requiring repeat confirmatory testing in a high percentage of patients ultimately diagnosed with GD (32.7%) and a high percentage of women with a positive screening test but without 100-g OGTT results (10.9%).

Please cite this article as: Pinés Corrales PJ, Villodre Lozano P, Quílez Toboso RP, Moya Moya AJ, López García MC. Prevalencia de diabetes gestacio-nal con una estrategia de 2 pasos y valores de corte del National Diabetes Data Group de 1979. ¿Estamos utilizando la mejor estrategia para nuestras pacientes? Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2022;69:450–452.