We describe in this article a case report of a 75-year-old woman who was admitted to the Short Stay Unit of our hospital in March 2023 due to a urinary infection associated with fever. She had a personal history of hypertension, osteoarthrosis, osteoporosis, irritative bowel syndrome and an IgG kappa multiple myeloma diagnosed in 2011 in advanced stage III-A. She had received five lines of active treatment for her myeloma and, as a lack of response was observed, the Haematology Department decided to withdraw active chemotherapy treatment in May 2022. Her daily medication consisted in: Valsartan 80mg/24h, Furosemide 40mg/24h, Mebeverine 135mg/8h, Diazepam 2mg/24h, Zolpidem 10mg/24h, Escitalopram 20mg/24h, one Fentanyl Parch 100mcg/h every 3 days, Paracetamol 1000mg/8h, four Pregabalin 25mg pills a day and Omeprazole 20mg/24h.

The basal status of the patient was that she was completely dependent on others to perform basic daily activities and had to eat shredded meals due to dysphagia.

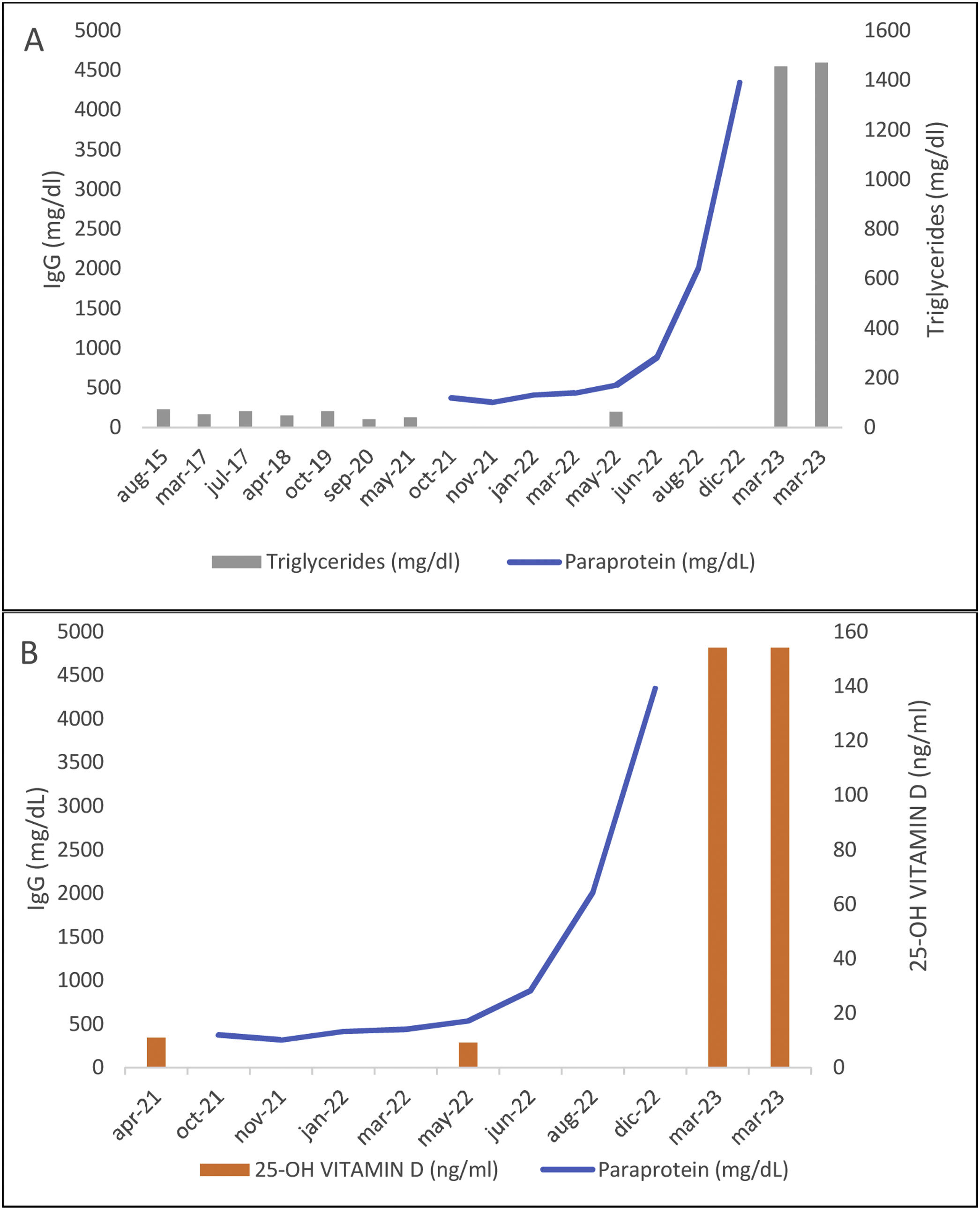

A complete blood test was performed, which included a lipid profile, liver function markers, renal function, electrolytes, PTH, 25-OH-vitamin D, vitamin B12 and a haemogram. The total cholesterol level was 11.84mmol/L (458mg/dl), HDL cholesterol 0.46mmol/L (18mg/dl), VLDL cholesterol 7.52mmol/L (291mg/dl) and triglycerides 16.44mmol/L (1455mg/dl). LDL cholesterol could not be calculated due to hypertriglyceridaemia. Moreover, the 25-OH-vitamin D levels were above the upper limit of detection (>154ng/ml), whilst serum calcium remained within normal values. The patient had never had such high levels of triglycerides, cholesterol or 25-OH-vitamin D. To rule out an error in the sample, a new one was taken, resulting in similar values: triglycerides 16.62mmol/L (1471mg/dl), 25-OH-vitamin D >384.37nmol/L (>154ng/ml) and the eGF rate was 113ml/min/1.73m2.

The anamnesis was completed with information obtained from the patient's daughter. She denied any changes in the patient's diet, and no sources of high fat or simple sugars were identified. She had not made any changes to her usual medication, and it was confirmed that the patient had not taken any vitamin D supplements. She did not present any limb oedemas or cutaneous xanthomas. Her last weight was 65kg, measured in July 2022, and her height was 1.58m, resulting in a body mass index of 26kg/m2. The daughter confirmed that she had not gained weight in recent months. Therefore, a secondary aetiology of the hypertriglyceridaemia was suspected. Possible secondary causes of hypertriglyceridaemia that should be considered include obesity, metabolic syndrome, diabetes mellitus, increased alcohol consumption, excessive caloric intake, hypothyroidism, kidney disorders (nephrotic syndrome), paraproteinemia, systemic lupus erythematosus, anorexia nervosa, glycogenosis, sepsis, pregnancy and drugs.1

It was decided to amplify the blood test with an HbA1c and TSH, to rule out undetected diabetes mellitus or hypothyroidism. Both results were normal: 5.27% and 5/63mIU/L, respectively. Furthermore, the patient appeared to have a low BMI, did not consume alcoholic beverages and was not known to have any rare diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus, glycogenosis, or anorexia nervosa, and none of the patient's current medications produced hypertriglyceridaemia. Glomerular filtration rate was normal, and proteinuria was negative.

Consequently, the most likely secondary cause of the hypertriglyceridaemia in this patient was paraproteinaemia. She had not been receiving active treatment for her multiple myeloma since May 2022 and no new blood tests that included triglycerides levels had been carried out until the current episode (Fig. 1a). This variant of multiple myeloma in which dyslipidaemia occurs is known as hyperlipidaemic myeloma.2

Relationship between paraprotein, triglycerides (A) and 25-OH-vitamin D levels (B). The sudden rise in triglycerides (A) and 25-OH-vitamin D (B) levels matches with the increase in paraprotein levels, even though they were not measured at the same time. May 2022 was the month when the active treatment against her myeloma was interrupted.

Hyperlipidaemic myeloma is a rare variant of multiple myeloma characterised by high triglycerides, LDL cholesterol levels and low levels of HDL cholesterol.2,3 Its clinical course, pathophysiology and the best therapy remain unknown. A pathophysiological mechanism has been proposed in which the paraprotein might bind to IDL and LDL lipoproteins, interfering with its receptor-mediated hepatic clearance. Moreover, it has also been suggested that paraprotein might bind to lipoprotein lipase reducing triglyceride metabolism.2,3 The largest review of this pathology was made by Misselwitz et al. in 2010, in which they reviewed 53 patients between 1937 and 2007. The most common type of myeloma was IgA in 53.3% of cases, whereas in conventional multiple myeloma, the most common type is IgG in 51.5% of cases.2 Recently, Rahman et al. detected the first case of hyperlipidaemic myeloma due to a light chain subtype.3

Misselwitz et al. observed that hyperlipidaemic myeloma can present either as an analytical alteration only or it can present with atherosclerosis, cutaneous xanthomas and/or hyperviscosity syndrome with either visceral or lower limb ischaemia or haemorrhages.2 Our patient did not present any cutaneous xanthomas in the physical examination.

As for the hypervitaminosis D, the main cause is overconsumption of oral supplements.4 However, the patient had not taken any vitamin D supplements. Ong et al. reported a case of hypervitaminosis D in a woman with IgG multiple myeloma who did not present any signs of toxicity.5 They concluded that paraprotein could interfere with immunoassay techniques used to measure vitamin D, resulting in high artefactual levels. Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry was later performed and confirmed normal values in the same patient.5 This is the most likely cause of hypervitaminosis D in our patient, as she previously presented low levels (Fig. 1b). However, we were not able to perform a confirmatory technique as the patient died from myeloma progression soon after our initial evaluation.

Hypervitaminosis D did not require any treatment as it was considered an artefactual finding.

Regarding the hypertriglyceridaemia, the use of lipid-lowering drugs does not effectively reduce lipid levels as the hyperparaproteinaemia persists.2,3,6 Lipid levels are reduced or even normalised when active treatment against multiple myeloma is applied and a good response is observed.2,3,6 Misselwitz et al. reported a considerable improvement or normalisation in triglyceride levels in 14 out of 33 patients who received chemotherapy, whereas only 1 out of 19 patients receiving fibrates normalised triglyceride levels.2 Therefore, lipid-lowering treatments were not initiated in this patient due to the probable poor response and the bad medical status of the patient.