Food composition tables and databases (FCTs or FCDBs) provide the necessary information to estimate intake of nutrients and other food components. In Spain, the lack of a reference database has resulted in use of different FCTs/FCDBs in nutritional surveys and research studies, as well as for development of dietetic for diet analysis. As a result, biased, non-comparable results are obtained, and healthcare professionals are rarely aware of these limitations. AECOSAN and the BEDCA association developed a FCDB following European standards, the Spanish Food Composition Database Network (RedBEDCA). wThe current database has a limited number of foods and food components and barely contains processed foods, which limits its use in epidemiological studies and in the daily practice of healthcare professionals.

Las tablas y las bases de datos de composición de alimentos (TCA o BDCA) proporcionan la información necesaria para estimar la ingesta de nutrientes y otros componentes alimentarios. En España la falta de una base de datos de referencia ha propiciado el uso de diferentes TCA/BDCA en encuestas nutricionales y estudios de investigación, así como en el desarrollo de programas dietéticos para el análisis de dietas. En consecuencia, se obtienen resultados sesgados y no comparables, y pocas veces el profesional sanitario es consciente de estas limitaciones. La AECOSAN y la asociación BEDCA desarrollaron una BDCA siguiendo estándares europeos, la Red Española de Bases de Datos de Composición de Alimentos (RedBEDCA). La base de datos actual tiene un número reducido de alimentos y componentes de alimentos y apenas contiene productos procesados, lo que limita su utilización en estudios epidemiológicos y en la práctica diaria del profesional de la salud.

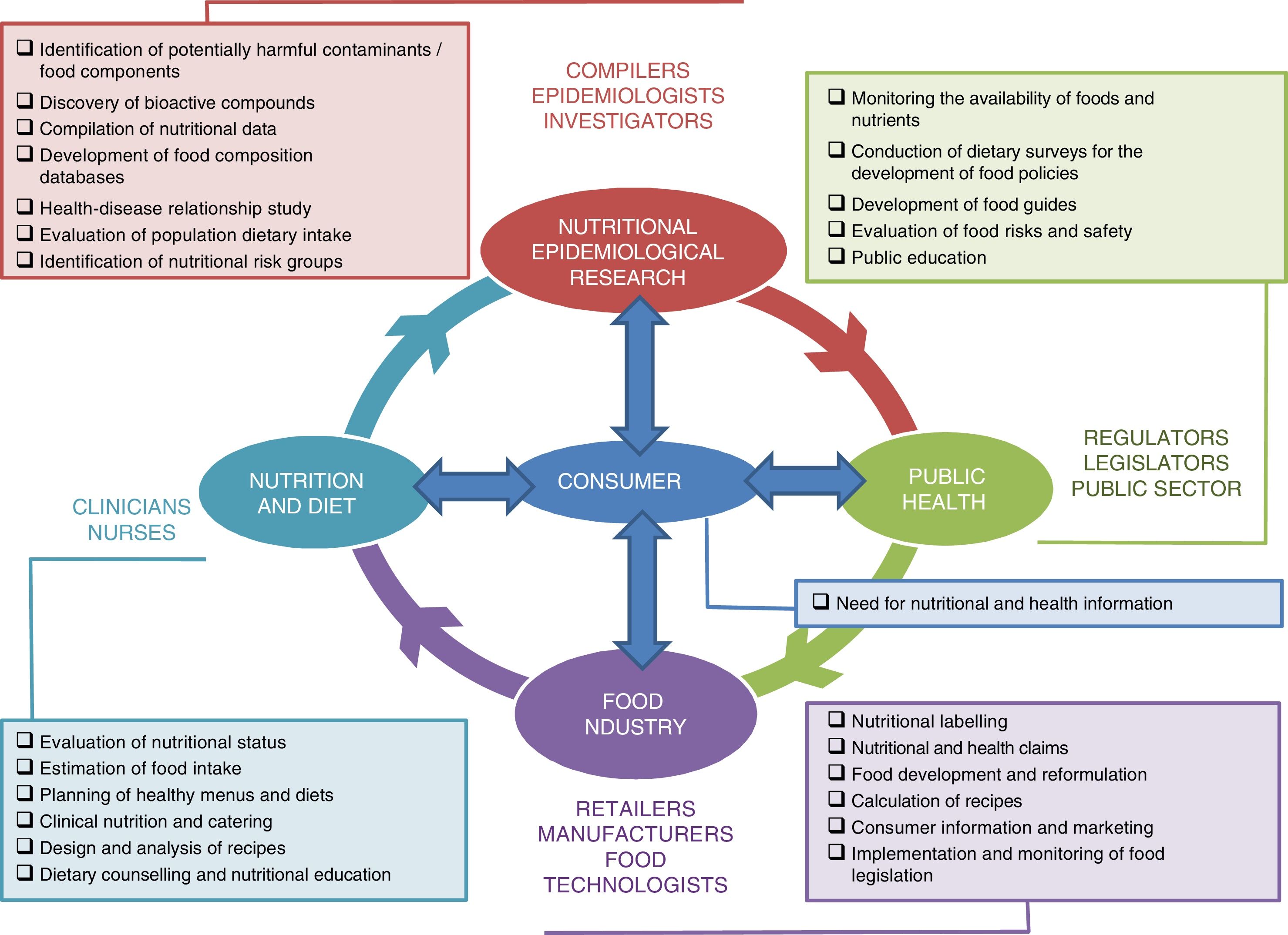

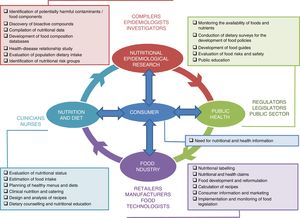

Food composition tables (FCTs) and food composition databases (FCDBs) provide information on the nutritional composition of foods and are key tools for the clinical practice of healthcare professionals. These tools are also used in different settings such as research, public health and education, the food industry, and in the development and implementation of government policies (Fig. 1). The first FCTs were published in paper format and were subsequently replaced by electronic versions known as FCDBs. The first European FCTs appeared in Germany in 1879–1880, and were published by König.1,2 However, the most widely known and complete FCT is the “Chemical composition of American food materials”, developed by Atwater and Woods3 in 1896 in the United States. Other European FCTs were subsequently published, including the English tables of McCance and Widdowson4 during the 1930s, the Dutch tables of van Eekelen, the Italian FCTs of the Instituto della Nutrizione in the 1940s, and the German tables of Souci in the 1960s.5 In Spain, the first initiatives of this kind date from 1932 in the form of two doctoral theses.6,7 Since then, different FCTs have been developed, though it was not until 2010 that the first official FCDB appeared in the form of the Spanish Food Composition Database (BEDCA) Network, of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation and under the coordination and funding of the Spanish Agency for Food Safety and Nutrition (AESAN) of the Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality.8,9

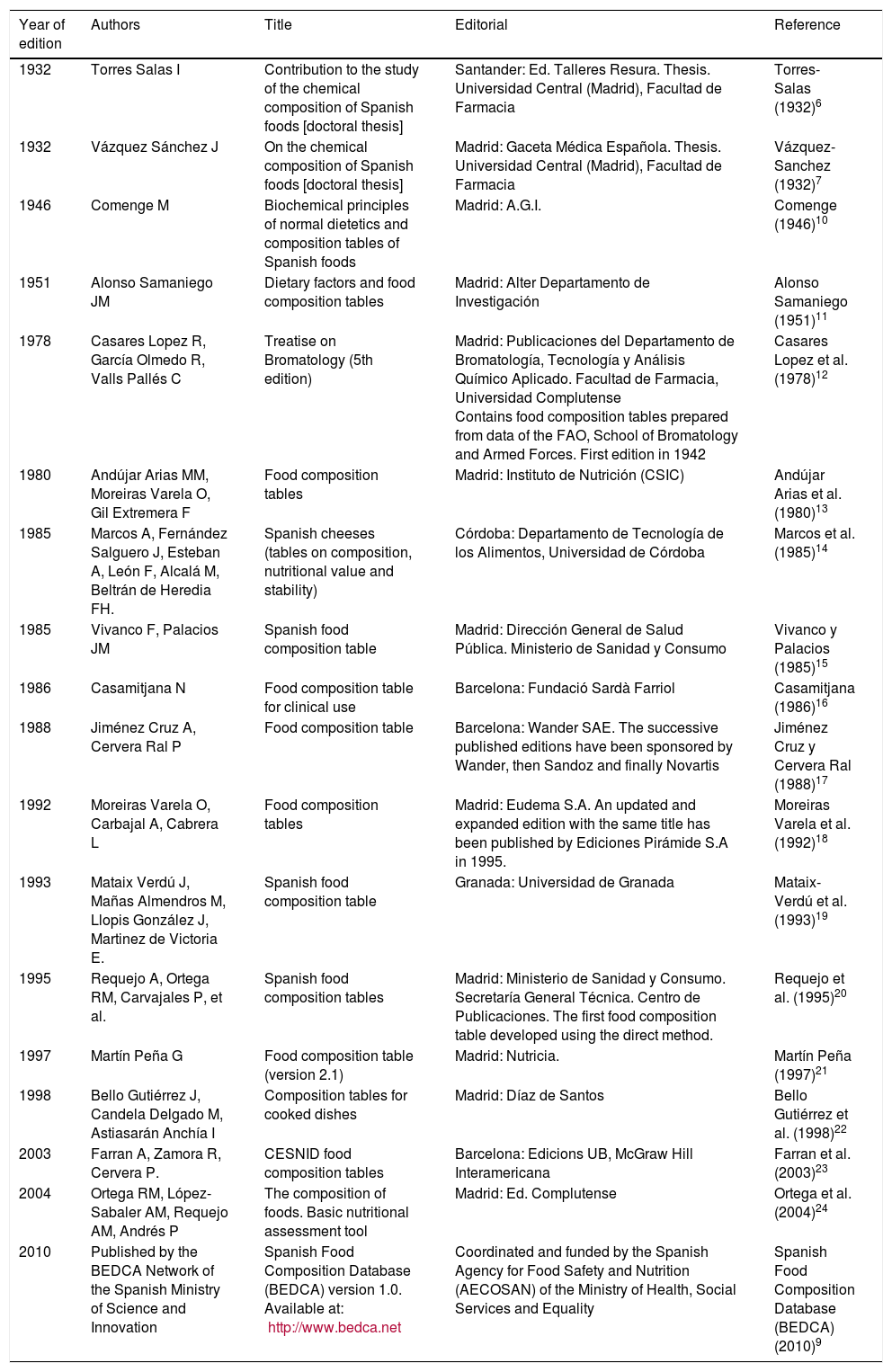

In contrast to other European countries, no references to FCTs can be found in Spain before the twentieth century. This is probably because there has been no organism in charge of generating an official FCT.8 To date, and to the best of our knowledge, 18 FCTs/FCDBs have been developed and published by universities, research centers and national laboratories, excluding works of a more informative nature or verbatim translations of foreign tables. Table 1 summarizes these studies.6,9–25 The FCTs generated in the 1990s and the first decade of this century are the tools that have had the greatest impact upon scientists and professionals in the field of nutrition. These include the FCT of Moreiras-Varela et al.,18 published by Ediciones de la Universidad Complutense (Eudema). Three years later Ediciones Pirámide, S.A. published an updated and expanded version. The latest edition appeared in 2016. The tables of Mataix-Verdú et al.,19 prepared by investigators of the Institute of Nutrition and Food Technology of the University of Granada, appeared in their most recent edition in 2009. Since its publication, this work has been a mandatory reference for pharmacists, physicians, dieticians and students alike. The work developed by Requejo et al.,20 of the Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs, was the first known attempt to produce a FCT using only the direct method. This approach involves specific analysis of all foods compiled in the database, implying strict control of data sampling, analysis and quality control. However, it is costly and slow. The food list was expanded in 1999, but does not exceed the figure of one hundred. Mention also should be made of the work generated by Martin-Peña,21 the original version of which was developed to minimize unknown nutrient data for each food; that of Bello-Gutiérrez et al.,22 of the Department of Bromatology, Food Technology and Toxicology of the University of Navarre, which contains information on the composition of the main foods cooked in Spain; that of Farran et al.,23 from the Center for Higher Education in Nutrition and Dietetics (CESNID), a center attached to the University of Barcelona; and that of Ortega et al.,24 of the Madrid Complutense University.

Food composition tables and databases published to date.

| Year of edition | Authors | Title | Editorial | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1932 | Torres Salas I | Contribution to the study of the chemical composition of Spanish foods [doctoral thesis] | Santander: Ed. Talleres Resura. Thesis. Universidad Central (Madrid), Facultad de Farmacia | Torres-Salas (1932)6 |

| 1932 | Vázquez Sánchez J | On the chemical composition of Spanish foods [doctoral thesis] | Madrid: Gaceta Médica Española. Thesis. Universidad Central (Madrid), Facultad de Farmacia | Vázquez-Sanchez (1932)7 |

| 1946 | Comenge M | Biochemical principles of normal dietetics and composition tables of Spanish foods | Madrid: A.G.I. | Comenge (1946)10 |

| 1951 | Alonso Samaniego JM | Dietary factors and food composition tables | Madrid: Alter Departamento de Investigación | Alonso Samaniego (1951)11 |

| 1978 | Casares Lopez R, García Olmedo R, Valls Pallés C | Treatise on Bromatology (5th edition) | Madrid: Publicaciones del Departamento de Bromatología, Tecnología y Análisis Químico Aplicado. Facultad de Farmacia, Universidad Complutense Contains food composition tables prepared from data of the FAO, School of Bromatology and Armed Forces. First edition in 1942 | Casares Lopez et al. (1978)12 |

| 1980 | Andújar Arias MM, Moreiras Varela O, Gil Extremera F | Food composition tables | Madrid: Instituto de Nutrición (CSIC) | Andújar Arias et al. (1980)13 |

| 1985 | Marcos A, Fernández Salguero J, Esteban A, León F, Alcalá M, Beltrán de Heredia FH. | Spanish cheeses (tables on composition, nutritional value and stability) | Córdoba: Departamento de Tecnología de los Alimentos, Universidad de Córdoba | Marcos et al. (1985)14 |

| 1985 | Vivanco F, Palacios JM | Spanish food composition table | Madrid: Dirección General de Salud Pública. Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo | Vivanco y Palacios (1985)15 |

| 1986 | Casamitjana N | Food composition table for clinical use | Barcelona: Fundació Sardà Farriol | Casamitjana (1986)16 |

| 1988 | Jiménez Cruz A, Cervera Ral P | Food composition table | Barcelona: Wander SAE. The successive published editions have been sponsored by Wander, then Sandoz and finally Novartis | Jiménez Cruz y Cervera Ral (1988)17 |

| 1992 | Moreiras Varela O, Carbajal A, Cabrera L | Food composition tables | Madrid: Eudema S.A. An updated and expanded edition with the same title has been published by Ediciones Pirámide S.A in 1995. | Moreiras Varela et al. (1992)18 |

| 1993 | Mataix Verdú J, Mañas Almendros M, Llopis González J, Martinez de Victoria E. | Spanish food composition table | Granada: Universidad de Granada | Mataix-Verdú et al. (1993)19 |

| 1995 | Requejo A, Ortega RM, Carvajales P, et al. | Spanish food composition tables | Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo. Secretaría General Técnica. Centro de Publicaciones. The first food composition table developed using the direct method. | Requejo et al. (1995)20 |

| 1997 | Martín Peña G | Food composition table (version 2.1) | Madrid: Nutricia. | Martín Peña (1997)21 |

| 1998 | Bello Gutiérrez J, Candela Delgado M, Astiasarán Anchía I | Composition tables for cooked dishes | Madrid: Díaz de Santos | Bello Gutiérrez et al. (1998)22 |

| 2003 | Farran A, Zamora R, Cervera P. | CESNID food composition tables | Barcelona: Edicions UB, McGraw Hill Interamericana | Farran et al. (2003)23 |

| 2004 | Ortega RM, López-Sabaler AM, Requejo AM, Andrés P | The composition of foods. Basic nutritional assessment tool | Madrid: Ed. Complutense | Ortega et al. (2004)24 |

| 2010 | Published by the BEDCA Network of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation | Spanish Food Composition Database (BEDCA) version 1.0. Available at: http://www.bedca.net | Coordinated and funded by the Spanish Agency for Food Safety and Nutrition (AECOSAN) of the Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality | Spanish Food Composition Database (BEDCA) (2010)9 |

Adapted and expanded from Ros et al.8

In Europe, the former Network of Excellence (NOE) of the European Community's Sixth Framework Program, the European Food Information Resource (EuroFIR), now the EuroFIR AISBL (http://www.eurofir.org), contributed to the harmonization of FCDBs and the creation of nutrient databases and other comparable components in more than 12 European countries. It has developed the Food Explorer tool, which makes it possible to compare the nutrient values of similar foods from different FCDBs in Europe, Australia, the United States and Canada. All the foods have been documented with the method of analysis of each component, including references and primary data sources. This initiative has also incorporated the LanguaL thesaurus for describing the foods. Currently, EuroFIR AISBL provides information on more than 60,000 foods, 13,000 recipes and 3500 brand foods.26

Due to the lack of an official and unified FCDB generated from the different Spanish FCTs and developed according to European recommendations, there is a need to produce a reference database with data compiled and documented according to European standards. In 2004, the AESAN, currently the Spanish Agency for Consumer Affairs, Food Safety and Nutrition (AECOSAN), created a working group that included two of the Spanish partners of the EuroFIR network – CESNID, of the University of Barcelona; and INTYA, of the University of Granada – to direct the creation of the first Spanish FCDB. Other research centers, universities, food industry associations (FIAB) and nutrition-related foundations (Triptolemus) were also involved in setting up the BEDCA Network. The first version of the BEDCA database was launched in 2010, allowing open and free access (www.bedca.net).9

The indirect method for data compilation was chosen. This means that the food composition values have been obtained from different sources, including scientific publications, the food industry, laboratories and calculated values.9 The foods were coded by the LanguaL system, and the Food Explorer tool was included.8,27,28 It has been used in the National Dietetic Intake Survey (ENIDE [2009–2010]) conducted by the AECOSAN, with the inclusion of over 3000 adults and more than 300,000 food entries.29 All the foods included in that study were added in version 2.0.28 The current version comprises a total of 950 foods, 34 components and 13 food groups.9,28

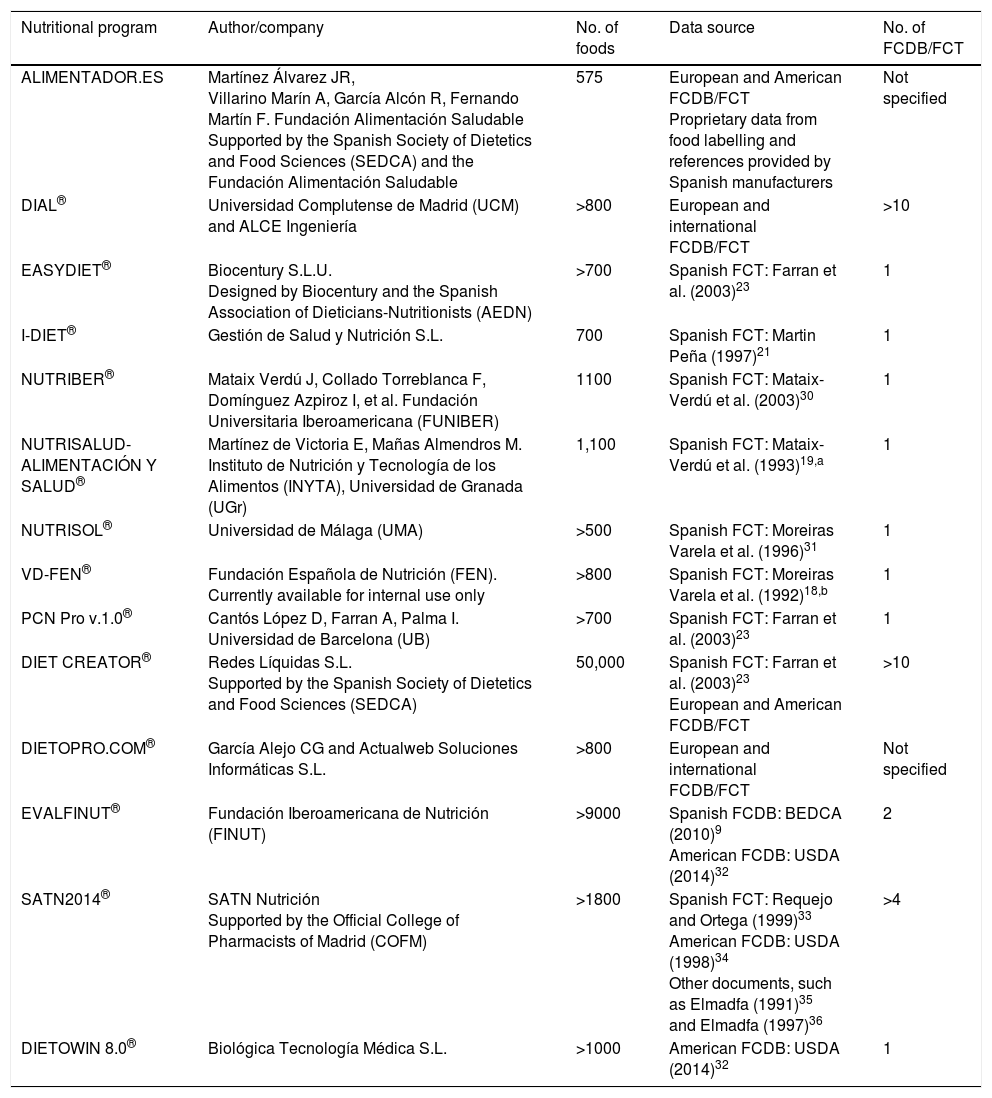

Nutritional programs for the analysis and preparation of dietsNutritional programs (NPs) are used by a great variety of users, including professionals and patients. Some of the main and commonly used Spanish NPs are detailed in Table 2 together with their corresponding FCTs/FCDBs.9,18,19,21,23,30–36 Out of a total of 14 NPs, 7 are based on a single national FCT or FCDB (EASYDIET®, i-DIET®, NUTRIBER®, NUTRISALUD®, NUTRISOL®, VD-FEN® and PCN Pro v.1.0®), 5 are based on several national and international FCTs or FCDBs (DIAL®, DIET CREATOR®, DIETOPRO.COM®, EVALFINUT® and SATN2014®); and one is also based on other sources such as the nutritional labelling and references provided by Spanish manufacturers (ALIMENTADOR.ES). Only one is based solely on the FCDB of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) (DIETOWIN 8.0®).

Main Spanish nutritional programs and their corresponding food composition tables and databases.

| Nutritional program | Author/company | No. of foods | Data source | No. of FCDB/FCT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALIMENTADOR.ES | Martínez Álvarez JR, Villarino Marín A, García Alcón R, Fernando Martín F. Fundación Alimentación Saludable Supported by the Spanish Society of Dietetics and Food Sciences (SEDCA) and the Fundación Alimentación Saludable | 575 | European and American FCDB/FCT Proprietary data from food labelling and references provided by Spanish manufacturers | Not specified |

| DIAL® | Universidad Complutense de Madrid (UCM) and ALCE Ingeniería | >800 | European and international FCDB/FCT | >10 |

| EASYDIET® | Biocentury S.L.U. Designed by Biocentury and the Spanish Association of Dieticians-Nutritionists (AEDN) | >700 | Spanish FCT: Farran et al. (2003)23 | 1 |

| I-DIET® | Gestión de Salud y Nutrición S.L. | 700 | Spanish FCT: Martin Peña (1997)21 | 1 |

| NUTRIBER® | Mataix Verdú J, Collado Torreblanca F, Domínguez Azpiroz I, et al. Fundación Universitaria Iberoamericana (FUNIBER) | 1100 | Spanish FCT: Mataix-Verdú et al. (2003)30 | 1 |

| NUTRISALUD-ALIMENTACIÓN Y SALUD® | Martínez de Victoria E, Mañas Almendros M. Instituto de Nutrición y Tecnología de los Alimentos (INYTA), Universidad de Granada (UGr) | 1,100 | Spanish FCT: Mataix-Verdú et al. (1993)19,a | 1 |

| NUTRISOL® | Universidad de Málaga (UMA) | >500 | Spanish FCT: Moreiras Varela et al. (1996)31 | 1 |

| VD-FEN® | Fundación Española de Nutrición (FEN). Currently available for internal use only | >800 | Spanish FCT: Moreiras Varela et al. (1992)18,b | 1 |

| PCN Pro v.1.0® | Cantós López D, Farran A, Palma I. Universidad de Barcelona (UB) | >700 | Spanish FCT: Farran et al. (2003)23 | 1 |

| DIET CREATOR® | Redes Líquidas S.L. Supported by the Spanish Society of Dietetics and Food Sciences (SEDCA) | 50,000 | Spanish FCT: Farran et al. (2003)23 European and American FCDB/FCT | >10 |

| DIETOPRO.COM® | García Alejo CG and Actualweb Soluciones Informáticas S.L. | >800 | European and international FCDB/FCT | Not specified |

| EVALFINUT® | Fundación Iberoamericana de Nutrición (FINUT) | >9000 | Spanish FCDB: BEDCA (2010)9 American FCDB: USDA (2014)32 | 2 |

| SATN2014® | SATN Nutrición Supported by the Official College of Pharmacists of Madrid (COFM) | >1800 | Spanish FCT: Requejo and Ortega (1999)33 American FCDB: USDA (1998)34 Other documents, such as Elmadfa (1991)35 and Elmadfa (1997)36 | >4 |

| DIETOWIN 8.0® | Biológica Tecnología Médica S.L. | >1000 | American FCDB: USDA (2014)32 | 1 |

FCDB: food composition database; FCT: food composition table.

The NP VD-FEN® has been developed by the Spanish Foundation of Nutrition (FEN), and is currently intended for internal use. This program (version 2.1) was created for the ANIBES study (Evaluation of the energy balance, anthropometry and food intake of the Spanish population), and is mainly based on a national FCT, with several expansions and updates.37

All the abovementioned NPs have databases of at least 500 foods, and even up to 50,000 foods, as in the case of DIET CREATOR®. Although many of them are supported by scientific bodies or Spanish foundations, the only NP based on the BEDCA is EVALFINUT®. The BEDCA is the only FCDB developed in Spain with data compiled and documented following European standards. This program also includes food composition data from the USDA.

The scientific bodies offer free online dietetic assessment tools. The Spanish Society of Hypertension (SEH-LELHA) (www.seh-lelha.org) offers a dietary intake calculator, whose food database has been extracted from the DIAL program.38 The Endocrinology and Nutrition Research Center of the University of Valladolid (www.ienva.org) provides various resources, including a diet calculator39 for healthcare professionals, and a mobile application (App) called Control de Dietas,40 aimed at the general public. Its premium version offers virtual consultation with an expert in Endocrinology. The Laboratory of Toxicology and Environmental Health of Rovira i Virgili University (URV) has developed an interactive website, Ribefood, which allows its users to determine the intake of micronutrients and macronutrients contained in widely consumed foods, and to know whether there is a health risk. The estimates are based on the French FCTs SU.VI.MAX (http://www.fmcs.urv.cat/ribefood/).41

Miguel Hernández University in turn has developed a food database with an integrated nutrition website, BADALI, allowing free access (http://badali.umh.es or http://badali.es). It contains nutritional information on processed products provided by manufacturers, along with other relevant information.42

Some research groups and pharmaceutical companies also develop open and free access NPs through their websites, or distributed by commercial companies. Examples of these are DIETSTAT®, PNUTRI® and DIETSOURCE®. The DIETSTAT program® (Carlos Haya Hospital, Málaga) has been developed to conduct dietary surveys and export nutritional data for statistical analysis. It is based on several sources, in particular on two Spanish FCTs (Mataix-Verdú et al.19 and Jiménez-Cruz and Cervera-Ral17). The PNUTRI program® (Carlos Haya Hospital, Málaga) in turn is based on a national FCT (Moreiras-Varela et al.)18 and a manual on fresh seafood from the Spanish Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Foods.43 The DIETSOURCE program® (developed by Nestlé Healthcare Nutrition Company) is a dietetic tool for planning customized diets.

The validity of the results provided by NPs largely depends on the quality of the food composition data. Therefore, when choosing an NP, the FCT or FCDB on which its calculations are based should be taken into account. Data quality refers to the suitability of the food values. This means that the values should be representative of the composition of the specified foods, and that the foods should be those consumed by the analyzed population.44 In this regard, some of these NPs are based on foreign FCTs or FCDBs, resulting in differences in food composition when comparisons are made with the national data, due to regional variations. Other NPs are of an open kind, allowing users to enter different modifications in the nutrient database that could affect the reliability of the original database.

There are other less obvious aspects that are often overlooked by the healthcare professional when choosing an NP, such as the frequency with which the database is updated; the contents referring to nutrients and components of interest; the inclusion of processed and brand products; the method for converting domestic measurements to standard weights; the procedures used to calculate the nutrient contents of recipes, dishes and menus; the database quality control procedures; the food search strategy; data extraction or nomenclature, etc.44

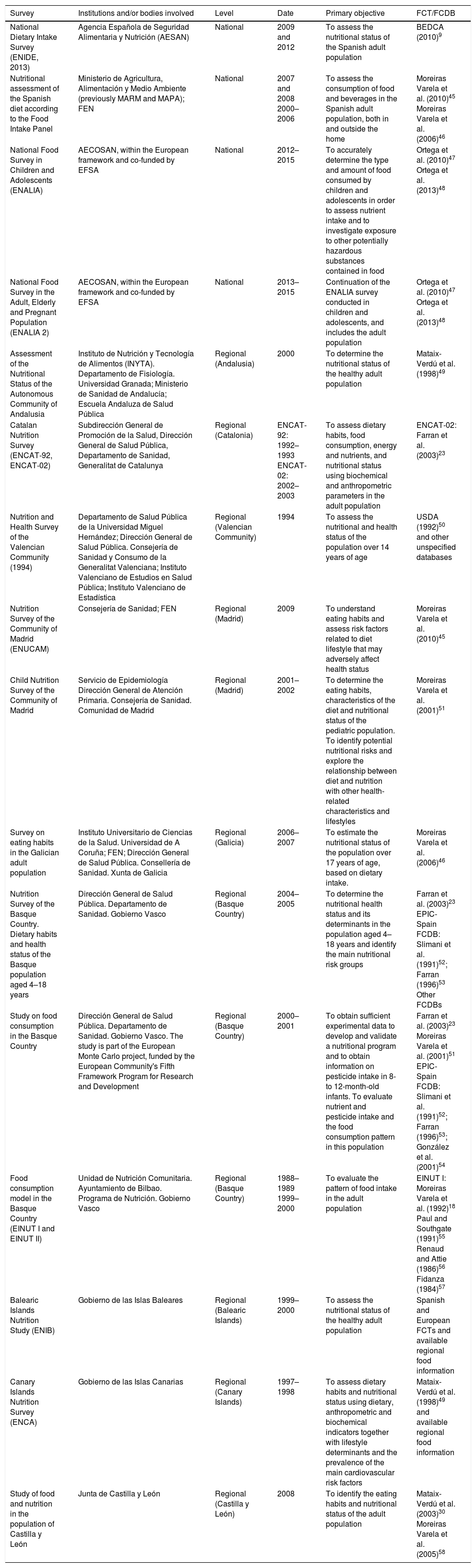

National surveys on dietary habitsTable 3 shows the main Spanish national and regional dietary and nutritional surveys conducted in the last 25 years. Those surveys not specifying the FCT/FCDB used for data analysis have been excluded. The table illustrates the diversity of FCTs/FCDBs9,18,23,30,45–58 used to transform food intake into energy and nutrient values, and subsequently to assess the suitability of dietary intakes. This circumstance introduces significant bias in the comparison of dietary intake results between national studies, and poses an obstacle to the participation of multicenter international evaluations.8

Main Spanish dietary and nutritional surveys conducted in the last 25 years, and their corresponding food composition tables and databases.

| Survey | Institutions and/or bodies involved | Level | Date | Primary objective | FCT/FCDB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National Dietary Intake Survey (ENIDE, 2013) | Agencia Española de Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutrición (AESAN) | National | 2009 and 2012 | To assess the nutritional status of the Spanish adult population | BEDCA (2010)9 |

| Nutritional assessment of the Spanish diet according to the Food Intake Panel | Ministerio de Agricultura, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente (previously MARM and MAPA); FEN | National | 2007 and 2008 2000–2006 | To assess the consumption of food and beverages in the Spanish adult population, both in and outside the home | Moreiras Varela et al. (2010)45 Moreiras Varela et al. (2006)46 |

| National Food Survey in Children and Adolescents (ENALIA) | AECOSAN, within the European framework and co-funded by EFSA | National | 2012–2015 | To accurately determine the type and amount of food consumed by children and adolescents in order to assess nutrient intake and to investigate exposure to other potentially hazardous substances contained in food | Ortega et al. (2010)47 Ortega et al. (2013)48 |

| National Food Survey in the Adult, Elderly and Pregnant Population (ENALIA 2) | AECOSAN, within the European framework and co-funded by EFSA | National | 2013–2015 | Continuation of the ENALIA survey conducted in children and adolescents, and includes the adult population | Ortega et al. (2010)47 Ortega et al. (2013)48 |

| Assessment of the Nutritional Status of the Autonomous Community of Andalusia | Instituto de Nutrición y Tecnología de Alimentos (INYTA). Departamento de Fisiología. Universidad Granada; Ministerio de Sanidad de Andalucía; Escuela Andaluza de Salud Pública | Regional (Andalusia) | 2000 | To determine the nutritional status of the healthy adult population | Mataix-Verdú et al. (1998)49 |

| Catalan Nutrition Survey (ENCAT-92, ENCAT-02) | Subdirección General de Promoción de la Salud, Dirección General de Salud Pública, Departamento de Sanidad, Generalitat de Catalunya | Regional (Catalonia) | ENCAT-92: 1992–1993 ENCAT-02: 2002–2003 | To assess dietary habits, food consumption, energy and nutrients, and nutritional status using biochemical and anthropometric parameters in the adult population | ENCAT-02: Farran et al. (2003)23 |

| Nutrition and Health Survey of the Valencian Community (1994) | Departamento de Salud Pública de la Universidad Miguel Hernández; Dirección General de Salud Pública. Consejería de Sanidad y Consumo de la Generalitat Valenciana; Instituto Valenciano de Estudios en Salud Pública; Instituto Valenciano de Estadística | Regional (Valencian Community) | 1994 | To assess the nutritional and health status of the population over 14 years of age | USDA (1992)50 and other unspecified databases |

| Nutrition Survey of the Community of Madrid (ENUCAM) | Consejería de Sanidad; FEN | Regional (Madrid) | 2009 | To understand eating habits and assess risk factors related to diet lifestyle that may adversely affect health status | Moreiras Varela et al. (2010)45 |

| Child Nutrition Survey of the Community of Madrid | Servicio de Epidemiología Dirección General de Atención Primaria. Consejería de Sanidad. Comunidad de Madrid | Regional (Madrid) | 2001–2002 | To determine the eating habits, characteristics of the diet and nutritional status of the pediatric population. To identify potential nutritional risks and explore the relationship between diet and nutrition with other health-related characteristics and lifestyles | Moreiras Varela et al. (2001)51 |

| Survey on eating habits in the Galician adult population | Instituto Universitario de Ciencias de la Salud. Universidad de A Coruña; FEN; Dirección General de Salud Pública. Consellería de Sanidad. Xunta de Galicia | Regional (Galicia) | 2006–2007 | To estimate the nutritional status of the population over 17 years of age, based on dietary intake. | Moreiras Varela et al. (2006)46 |

| Nutrition Survey of the Basque Country. Dietary habits and health status of the Basque population aged 4–18 years | Dirección General de Salud Pública. Departamento de Sanidad. Gobierno Vasco | Regional (Basque Country) | 2004–2005 | To determine the nutritional health status and its determinants in the population aged 4–18 years and identify the main nutritional risk groups | Farran et al. (2003)23 EPIC-Spain FCDB: Slimani et al. (1991)52; Farran (1996)53 Other FCDBs |

| Study on food consumption in the Basque Country | Dirección General de Salud Pública. Departamento de Sanidad. Gobierno Vasco. The study is part of the European Monte Carlo project, funded by the European Community's Fifth Framework Program for Research and Development | Regional (Basque Country) | 2000–2001 | To obtain sufficient experimental data to develop and validate a nutritional program and to obtain information on pesticide intake in 8- to 12-month-old infants. To evaluate nutrient and pesticide intake and the food consumption pattern in this population | Farran et al. (2003)23 Moreiras Varela et al. (2001)51 EPIC-Spain FCDB: Slimani et al. (1991)52; Farran (1996)53; González et al. (2001)54 |

| Food consumption model in the Basque Country (EINUT I and EINUT II) | Unidad de Nutrición Comunitaria. Ayuntamiento de Bilbao. Programa de Nutrición. Gobierno Vasco | Regional (Basque Country) | 1988–1989 1999–2000 | To evaluate the pattern of food intake in the adult population | EINUT I: Moreiras Varela et al. (1992)18 Paul and Southgate (1991)55 Renaud and Attie (1986)56 Fidanza (1984)57 |

| Balearic Islands Nutrition Study (ENIB) | Gobierno de las Islas Baleares | Regional (Balearic Islands) | 1999–2000 | To assess the nutritional status of the healthy adult population | Spanish and European FCTs and available regional food information |

| Canary Islands Nutrition Survey (ENCA) | Gobierno de las Islas Canarias | Regional (Canary Islands) | 1997–1998 | To assess dietary habits and nutritional status using dietary, anthropometric and biochemical indicators together with lifestyle determinants and the prevalence of the main cardiovascular risk factors | Mataix-Verdú et al. (1998)49 and available regional food information |

| Study of food and nutrition in the population of Castilla y León | Junta de Castilla y León | Regional (Castilla y León) | 2008 | To identify the eating habits and nutritional status of the adult population | Mataix-Verdú et al. (2003)30 Moreiras Varela et al. (2005)58 |

Surveys failing to specify the source used to transform food into energy and nutrients are excluded.

AECOSAN: Spanish Agency for Consumer Affairs, Food Safety and Nutrition; EFSA: European Food Safety Authority; EPIC: European Prospective Investigation into Cancer; FCDB: food composition database; FEN: Spanish Nutrition Foundation; FCT: food composition table.

In 2009, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) published the guide General principles for the collection of national food consumption data in the view of a pan-European dietary survey, and launched a pan-European food consumption survey, also known as the “EU Menu”.59 In this regard, the National Survey on Food in the Adult, Elderly and Pregnant Population (ENALIA2) followed the EFSA guidelines and was included in the EU Menu project. Data were recorded and managed with the NP ENIA Soft, which had previously been implemented in the National Survey on Food in Children and Adolescents (ENALIA).60 This program is based on a national FCT.45,48

The ENIDE is the only survey to have used the BEDCA database developed by the AECOSAN, and is the only Spanish FCDB with data compiled and documented following EuroFIR standards.29

Factors influencing variability in the accuracy of the food composition tablesNutrient composition in food can be affected by a variety of parameters including environmental, genetic and geographical factors, seasonal variations, bioavailability, biodiversity, technological processes within the food chain, storage conditions, enrichment policies, market globalization, the growing availability of processed products, and cooking methods.61

Many of these factors are difficult to control, such as seasonal variation or biodiversity. Seasonal variations affect food composition, especially as regards micronutrients and bioactive substances in plant foods.62 Unprocessed foods may also vary considerably in nutrient content from one country to another, due to biodiversity.

Other factors can be controlled, or at least should be taken into account, such as regional disparities. Each country has specific data regarding food composition needs, since there is a proprietary pattern of intake resulting in country-specific foods, recipes and food brands. Some users may mistakenly believe that food composition is similar among countries, due to globalization. However, commercial foods sold under the same brand names may have different compositions due to differences in food legislation.61

Analytical methods can greatly affect nutrient composition. The different analytical methods used for the same component, in addition to natural variation, could be the main reason for the discrepancies found among the national databases. For example, the values referring to raw fiber versus dietary fiber or cholesterol obtained by spectrometric analysis versus gas-liquid chromatography differ greatly. In addition, many of the more complete FCTs/FCDBs include both values obtained by direct analysis and non-analytical values derived from several estimation procedures.63

Differences in food nomenclature and food groups, different forms of food classification and identification, variations in units and forms of expression, the various calculation procedures for missing values, and the lack of a data quality assessment all affect food composition data. However, most of these factors can be controlled by using standardized procedures.

Limitations of the national food composition tables and databasesThe great majority of Spanish national FCTs have been developed using the indirect method and the combined method, imputing values from foreign tables, and with coexisting analytical data.64 In many cases, there is no clear and detailed documentation of the analytical methods corresponding to the different components or the source of the data. The sole exception is the FCT developed by the Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs. However, it contains only 68 foods and 25 components.20 Likewise, no data are provided regarding nutrients such as starch, sugars and lactose, among others. The table also omits copper, selenium and other minerals, as well as certain vitamins, such as vitamin B5 (pantothenic acid), biotin, and vitamin K.

The different FCTs pose problems regarding synonyms, homonyms, identical names for different products, and the use of diverse cooking and technological terminology.8,27,65 There are also no unified classification criteria, particularly as regards the classification of beverages.66

In sum, Spanish FCTs have significant weaknesses. They include a low number of foods and food components; there is only a small percentage of original analytical values (most are adopted and imputed values taken from other national or foreign databases and different literature sources); there is a lack of traceability for many data (information origin and documentation method is not available or is not appropriate); most of the databases have no clear classification of foods allowing unequivocal identification; and the tables contain few routinely consumed processed foods.67

The BEDCA is the only Spanish FCDB developed with data compiled and documented following EuroFIR AISBL standards. However, the current official database has a limited number of foods compared with the USDA database in the United States (USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, release 28), which contains data on 8789 foods and up to 150 components.68 Furthermore, it does not include processed food products commonly consumed by the Spanish population or products destined for specific nutritional use, in contrast to the situation found in other European FCDBs. Likewise, it does not include components that play an important role in human health and for which knowledge of the amounts present in commonly consumed foods is important, such as trans fatty acids, added sugars, bioactive compounds, etc.

The lack of a reference FCDB has led to the use of different FCTs/FCDBs in dietary surveys and nutritional studies of the Spanish population, giving rise to discordant values of the different components analyzed. This introduces considerable bias in the estimates of nutrient intake and gives rise to data quality problems.65,67

The study carried out by San Mauro-Martin and Hernández-Rodríguez69 showed the variability among the different FCTs and NPs commonly used in Spain by nutrition professionals, thus calling into question the scientific validity of these tools. The authors designed and analyzed a weekly menu and calibrated it using the ALIMENTADOR.ES program, which was subsequently validated with NPs such as DIAL® and EASYDIET®, and with other national FCTs/FCDBs such as those of Farran et al.23, Mataix-Verdú et al.19 and Moreiras Varela et al.,18 and the BEDCA.9 The same ingredients and quantities were selected to establish an objective comparison of the results. Many nutrients could not be compared due to missing values. The comparable data ranges obtained for each nutrient showed a variability of 8–84%, being greater for micronutrients than for macronutrients or energy.

The present study has not analyzed NPs in App format.

Current status and future perspectivesIn Spain, we currently have a large number of FCTs/FCDBs developed by different bodies and institutions, mainly within the academic setting. We also have the BEDCA database developed by the BEDCA Network. This network includes public research centers, government and private institutions, and has been created with the support of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation and funded and coordinated by the AESAN, of the Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality. These tools all have significant weaknesses, such as the data compilation method used, the presence of missing values, and the limited number of included foods and dishes. Despite the initiative driven by the AESAN – the aim of which was to develop and maintain a Spanish FCDB – there is still no national reference FCDB, in contrast to the situation found in many other advanced countries. This may be explained by the lack of an official body responsible for generating a reference FCDB.

Taking the United States as an example, there the Department of Agriculture has been the body responsible for the creation, maintenance and continuity of the food and nutrient databases at the national level for over 100 years, with an origin that goes back to the first FCT developed by Atwater and Woods in 1896. The Beltsville Human Nutrition Research Center (BHNRC), which is part of the Agricultural Research Service (ARS), is responsible for publishing the four main databases in the United States: The USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference (SR), the Dietary Supplement Ingredient Database, the Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies, and the USDA Food Patterns Equivalents Database. All the food and nutrient information used in the country is derived only from these sources and encompasses the main areas of application: food and health research, the monitoring of dietary intake and the definition of food policies, and dietary practice.70

The USDA food and nutrient databases are currently an international reference, as they are the most complete, reliable and up-to-date instruments of their kind. This has been made possible by the association of, and collaboration between, the Government and key public/private sector users and stakeholders in mobilizing funding or scientific experience with the aim of improving the databases. Direct analyses of foods sampled throughout the country are periodically carried out to replace older analytical data with data from the published literature and small research studies, and to include new foods.70

Following the example of the United States, in Spain we need to create an official body responsible for generating, maintaining and continuing a Spanish national reference FCDB. This body could be composed of leading scientific bodies in the field of Nutrition and Bromatology, Food Science and Technology, and Medicine. Collaboration on the part of the food industry is undoubtedly necessary to contribute analytical data on the composition of processed products. Only in this way can a reference FCDB be guaranteed, with reliable, accurate and usable data for all sectors of society.

ConclusionsIt is essential to have a consistent, reliable, complete and up-to-date database capable of becoming the Spanish national reference FCDB for the conduction of dietary surveys and epidemiological studies. Such a FCDB in turn would serve for the design of NPs based on reliable and quality data, allowing healthcare professionals to analyze the dietary intakes of their patients (particularly those with special needs), and to establish more adequate nutritional recommendations.

Financial supportThis study was funded by the Secretariat of Universities and Research of the Department of Enterprise and Knowledge of the Catalan Government and the European Social Fund (predoctorate grant FI No. 2016FI B 00211).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Lupiañez-Barbero A, González Blanco C, de Leiva Hidalgo A. Tablas y bases de datos de composición de alimentos españolas: necesidad de un referente para los profesionales de la salud (revisión). Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2018;65:361–373.