Our group has recently communicated how type 2 diabetes (T2D) and high levels of fasting plasma glucose (FPG) are independent risk factors for daytime sleepiness and sleep quality, suggesting the role of sleep questionnaires to evaluate the relationship between T2D and sleep breathing disorders.1 We now provide additional results obtained through the administration of other two specific questionnaires in order to investigate the deleterious effect of T2D and the degree of glycemic control on the risk of having sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome (SAHS) and quality of life. For this purpose, both questionnaires were administered to a total of 331 patients at the time of a regular visit to the outpatient diabetes unit from Arnau de Vilanova and Vall d’Hebron University Hospitals among February 2012 and December 2014: (i) the Berlin Questionnaire, to measure the risk of having sleep apnea, and (ii) the Quebec Sleep Questionnaire (QSQ) to assess health related quality of life in patients with sleep apnea.

Recruited patients were able to read and recognize the correct meaning of the questions, and also were older than 18 years, of Caucasian origin, and with known T2D for longer than 5 years. In addition, they do not report any nighttime hypoglycemia events or previous episodes of severe hypoglycemia, and a determination of FPG and glycated hemoglobin during the preceding months was available. Subjects with chronic lung illnesses, heart or stroke failure, use of sedatives or alcohol abuse, as well as shift workers, were excluded. Therefore, only data from 135 subjects with T2D were assessed. We designed a case-control study, and one control was selected for every three cases. Then 45 subjects without diabetes and matched to cases by age (59.0±12.0 vs. 60.9±12.6; p=0.383), gender (55% of women in each group), BMI (29.6±7.0 vs. 30.9±5.3; p=0.192), and smoking status were carefully chosen. In all cases, informed consent was obtained.

Treatment for T2D was assorted, and comprised metformine alone (20.7%), different oral treatment combinations (13.8%), metformin plus basal insulin (42.9%), and basal plus or basal bolus therapy (19.2%). Only four patients were under diet alone (2.9%), and none subject included in this study was treated with glucagon like peptide-1 analogs.

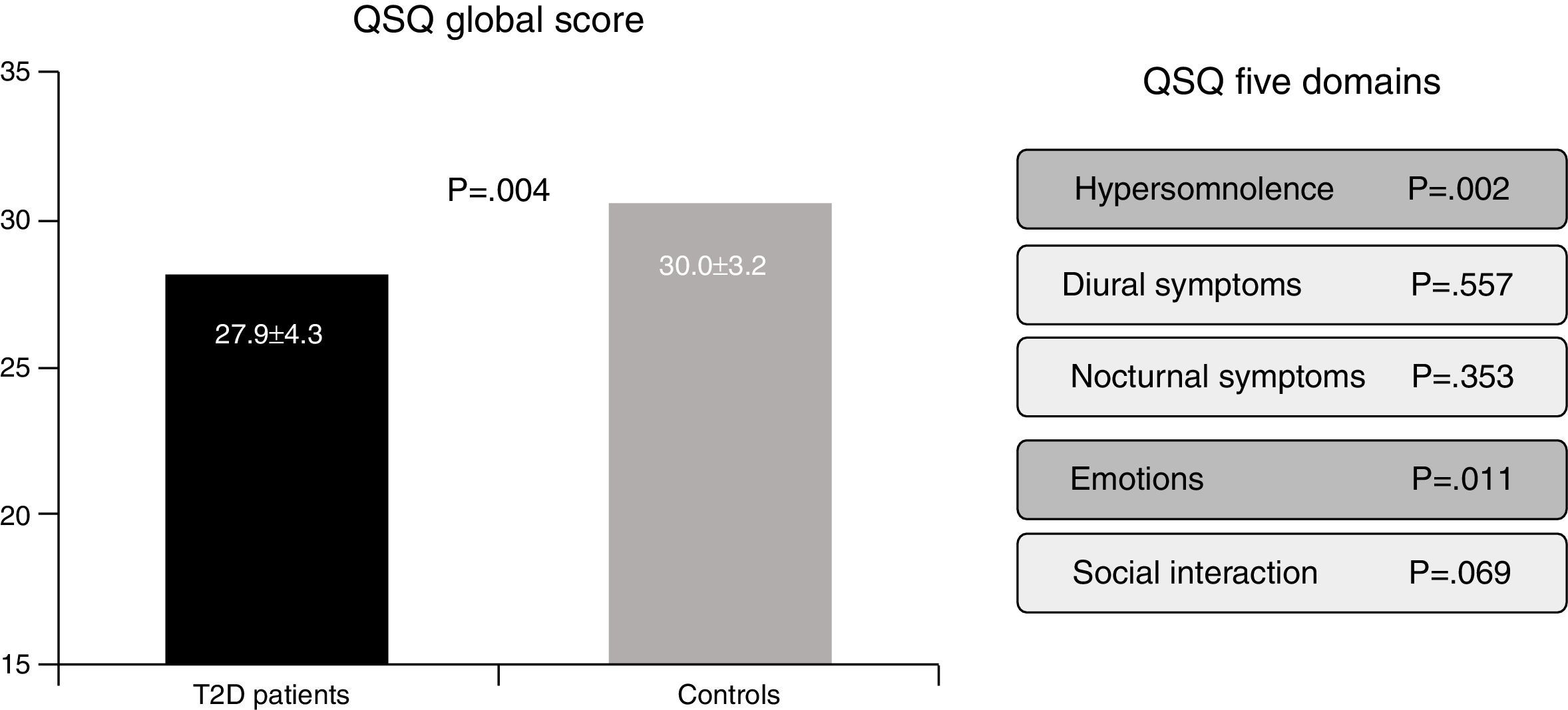

In the Berlin Questionnaire eleven items cover three domains related to risk of obstructive sleep apnea: (i) snoring and sleep-related symptoms, (ii) awake-time sleepiness and drowsiness, and (iii) hypertension and/or a BMI greater than 30kg/m2.2,3. Responses are coded present or absent for each category, and the final score ranges from 0 to 3. Subjects who score ≥2 are classified as high risk, whereas subjects who score <2 are classified as low risk. Finally, the QSQ is a valid tool to assess, through 32 questions, how SAHS can be implicated in influencing five health related quality of life domains: hypersomnolence, diurnal symptoms, nocturnal symptoms, emotions and social interactions.4,5 Lower scores reflect worse subjective sleep quality (Fig. 1).

The risk of SAHS, as defined by the Berlin questionnaire, was present in the 58.8% of the whole population, and this group of “high risk” subjects was associated with lower health related quality of life (QSQ: 26.9±4.3 vs. 30.2±3.1, p<0.001). In addition, a higher percentage of patients with T2D in comparison with control subjects were classified as high risk for SAHS (60.0% vs. 40%, p=0.015). Furthermore, a lower health related quality of life was present in patients with T2D (QSQ global score: 27.9±4.3 vs. 30.0±3.2, p=0.004), mainly in domains related with daily somnolence (5.6±1.1 vs. 6.1±0.7, p=0.002) and emotions (5.8±1.1 vs. 6.3±0.7, p=0.011). However, no differences in diurnal symptoms (6.3±0.8 vs. 6.4±0.8, p=0.557), nocturnal symptoms (5.1±1.2 vs. 5.3±1.2, p=0.353) nor social interaction (6.0±0.8 vs. 6.2±0.6, p=0.069) were detected.

In the univariate analysis, a significant correlation between FPG and glycated hemoglobin was found only with the domain related with emotions (r=−0.267, p=0.001 and r=−0.182, p=0.039, respectively). A stepwise regression analysis showed that the presence of T2D (beta=−0.185, p=0.001) and BMI (beta=−0.198, p=0.012), but age or gender independently predicted the QSQ global score (R2=0.081).

Overall, our results confirm that patients with T2D are a population at risk of SAHS by using the Berlin Questionnaire and also provide evidence for implementing a more accurate screening for SAHS in patients with T2D. Some boundaries should be managed when evaluating the results of our work. The former, as a cross-sectional study we cannot draw a causal relationship between T2D and daytime consequences associated to sleep disturbances. However, the problem is clinically relevant since the prevalence of SAHS in subjects with T2D reaches the 40% to 86%, in comparison to the 2–4% in general population.6,7 Second, we administered to patients with T2D a specific questionnaire to evaluate health-related quality of life in patients with SAHS. We assumed that a great percentage of patients with T2D will experience intermittent hypoxia and sleep disruption.8–10 For these reason we found remarkable to investigate the association between perceived sleep and life quality in T2D patients. Third, more than half of subjects with T2D were under insulin therapy. Therefore, although no nighttime hypoglycemia episodes were reported, we cannot rule out the occurrence of unawareness events during the sleeping time that could influence our results.

In conclusion, T2D is associated with worse scores in administered questionnaires evaluating the risk of having SAHS, and quality of life associated to sleep breathing disorders. As questionnaires are simple and economic screening instruments that easily can be used and quickly scored in a demanding clinical practice, our findings highlight the importance of screening subjects with T2D for sleep problems, making an appointment to a sleep medicine specialist if appropriate, and suggesting sleep hygiene approaches as part of diabetes care.

FundingNo other sources of funding exist.

Conflict of interestNo potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

This work was supported by grants from de Instituto de Salud Carlos III ISCIII (Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria, FI12/00803) and Fundación Sociedad Española Endocrinología y Nutrición (FSEEN). CIBER de Diabetes y Enfermedades Metabólicas Asociadas (CIBERDEM) and CIBER de Enfermedades Respiratorias (CIBERES) are an initiative of the Instituto Carlos III.