Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a field of knowledge that continues to experience exponential growth. As a result, the management paradigms have changed, shifting the glucocentric view of the disease towards a vision in which different variables (social, age, organic) are taken into account when determining the treatment objective. The development of new families of drugs (SGLT2 inhibitors, GLP-1 analogues) and their benefits beyond their hypoglycaemic effect also influence our treatment algorithms.1,2 However, there is a non-modifiable factor that we may not be taking into account when making our decisions: the influence of the gender factor (as a biological and social factor).

There is a large body of evidence suggesting that the expression of the disease and its complications are not the same in males and females: disease onset is earlier age in males, but as age advances it becomes equal in both genders3 and the male/female ratio is projected to reach around 1:1 in the coming years; females can develop a specific type of diabetes (gestational diabetes mellitus), which leads to a 9.51 times higher risk of developing diabetes outside pregnancy (P < .001; 95% CI: 7.14–12.67),4 and differences have also been described in the complications tree.3 In general terms, males have a higher incidence and severity of microvascular complications (both in DM1 and DM2),5 while with macrovascular complications, the opposite is the case; it is striking that both the incidence and mortality rate due to coronary complications are distinctly higher in females than in males (increase in the incidence of coronary artery disease of 3–5 times in females and 1–3 times in males with DM2 compared to individuals without DM,5,6 with 6.4 years of life lost in females under 50 compared to 5.8 years of life lost in males).3 It seems that cerebrovascular disease is also more prevalent and fatal in women (without being as evident as in coronary disease).5,6

While there are no conclusive data on peripheral arterial disease in DM1,5 in young women with DM2 it leads to a higher mortality risk than in their male counterparts, although, in absolute terms, it is more common and causes more deaths in males.6

Since 2007, with its resolution WHA60.25 and the subsequent “Strategy for integrating gender analysis and actions into the work of WHO”,7 the World Health Organization has been committed to integrating gender analysis into all its actions and pressing for the data from its studies to be broken down by such variables as gender and age. It also advocates following the same recommendations when publishing the results of scientific research.

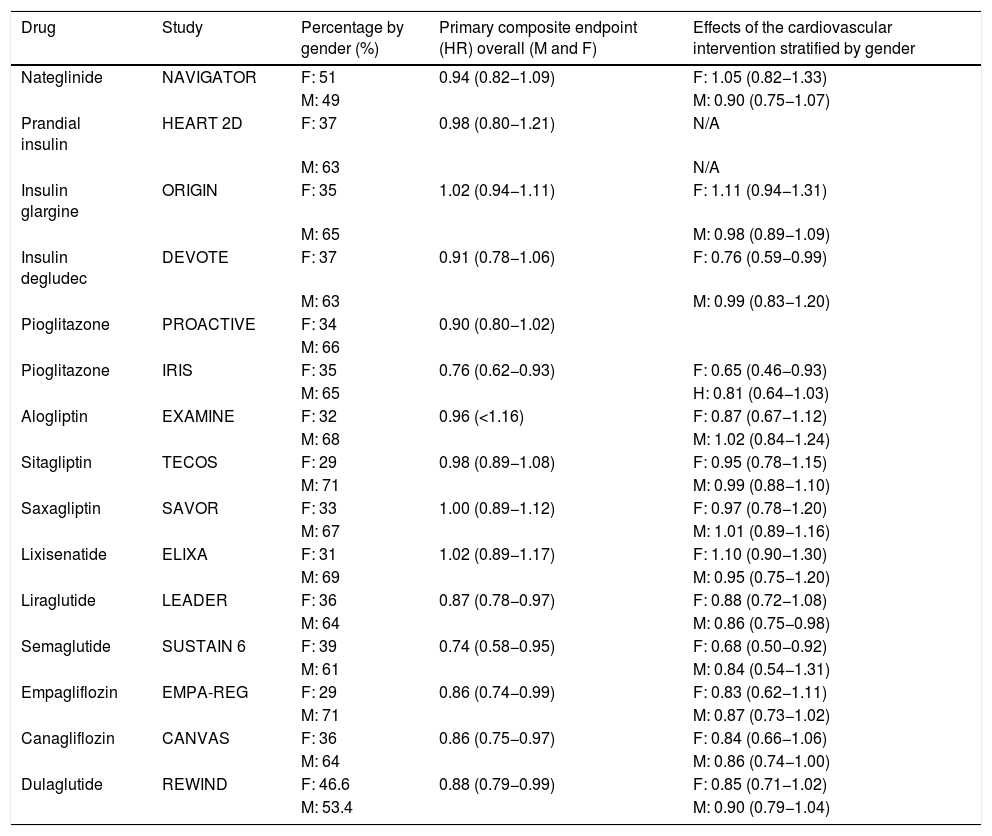

If we look back at the results of the cardiovascular safety studies for the drugs approved for the treatment of DM published since the Food and Drug Administration resolution in 2008, we can conclude that, in general, the number of females included in these studies represented 30%–40% of the total number of participants.8 A review published in 2018 by Gerstein and Shah8 analysed the cardiovascular outcomes from the safety studies published to date stratified by gender (Table 1). Although all the drugs analysed have proven to be safe in females, from a statistical point of view, cardiovascular benefit is described with pioglitazone and degludec. Since that review, we have seen the publication of the REWIND study (dulaglutide)9 showing cardiovascular safety, but without superiority of its primary composite endpoint (myocardial infarction or non-fatal stroke or death from cardiovascular causes; P = .90; 95% CI: 0.79–1.04), while in the studies of the VERTIS series (ertugliflozin),10 the data published were not stratified by gender.

Cardiovascular outcomes stratified by gender.

| Drug | Study | Percentage by gender (%) | Primary composite endpoint (HR) overall (M and F) | Effects of the cardiovascular intervention stratified by gender |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nateglinide | NAVIGATOR | F: 51 | 0.94 (0.82−1.09) | F: 1.05 (0.82−1.33) |

| M: 49 | M: 0.90 (0.75−1.07) | |||

| Prandial insulin | HEART 2D | F: 37 | 0.98 (0.80−1.21) | N/A |

| M: 63 | N/A | |||

| Insulin glargine | ORIGIN | F: 35 | 1.02 (0.94−1.11) | F: 1.11 (0.94−1.31) |

| M: 65 | M: 0.98 (0.89−1.09) | |||

| Insulin degludec | DEVOTE | F: 37 | 0.91 (0.78−1.06) | F: 0.76 (0.59−0.99) |

| M: 63 | M: 0.99 (0.83−1.20) | |||

| Pioglitazone | PROACTIVE | F: 34 | 0.90 (0.80−1.02) | |

| M: 66 | ||||

| Pioglitazone | IRIS | F: 35 | 0.76 (0.62−0.93) | F: 0.65 (0.46−0.93) |

| M: 65 | H: 0.81 (0.64−1.03) | |||

| Alogliptin | EXAMINE | F: 32 | 0.96 (<1.16) | F: 0.87 (0.67−1.12) |

| M: 68 | M: 1.02 (0.84−1.24) | |||

| Sitagliptin | TECOS | F: 29 | 0.98 (0.89−1.08) | F: 0.95 (0.78−1.15) |

| M: 71 | M: 0.99 (0.88−1.10) | |||

| Saxagliptin | SAVOR | F: 33 | 1.00 (0.89−1.12) | F: 0.97 (0.78−1.20) |

| M: 67 | M: 1.01 (0.89−1.16) | |||

| Lixisenatide | ELIXA | F: 31 | 1.02 (0.89−1.17) | F: 1.10 (0.90−1.30) |

| M: 69 | M: 0.95 (0.75−1.20) | |||

| Liraglutide | LEADER | F: 36 | 0.87 (0.78−0.97) | F: 0.88 (0.72−1.08) |

| M: 64 | M: 0.86 (0.75−0.98) | |||

| Semaglutide | SUSTAIN 6 | F: 39 | 0.74 (0.58−0.95) | F: 0.68 (0.50−0.92) |

| M: 61 | M: 0.84 (0.54−1.31) | |||

| Empagliflozin | EMPA-REG | F: 29 | 0.86 (0.74−0.99) | F: 0.83 (0.62−1.11) |

| M: 71 | M: 0.87 (0.73−1.02) | |||

| Canagliflozin | CANVAS | F: 36 | 0.86 (0.75−0.97) | F: 0.84 (0.66−1.06) |

| M: 64 | M: 0.86 (0.74−1.00) | |||

| Dulaglutide | REWIND | F: 46.6 | 0.88 (0.79−0.99) | F: 0.85 (0.71−1.02) |

| M: 53.4 | M: 0.90 (0.79−1.04) |

Looking at these data, the question we asked as title to this letter seems all the more important. Specific studies in female subjects are needed to guide us towards the best therapeutic decision-making for women and girls with DM.

FundingNo funding was received.