The most common clinical presentation of primary hyperparathyroidism (PHP) is asymptomatic hypercalcemia, and diagnosis of PHP based on the presence of bone manifestations such as osteitis fibrosa cystica (OFC) is increasingly uncommon. OFC occurs in less than 5% of patients with PHP and suggests a more severe or long-standing disease. OFC is characterized by the occurrence of bone pain associated with the finding of specific radiographic changes such as increased subperiosteal bone resorption in the distal third of the radius and middle phalanges, distal clavicular thinning, “salt and pepper” skull, bone cysts, and brown tumors in long bones. Brown tumors result from bone demineralization with osteoclast activation, microhemorrhages, and microfractures, and are so named because of their typical color, due to abundant hemosiderin deposits. Histopathologically, a combination of osteoclastic and osteoblastic activity with cyst formation and many hemosiderin-laden macrophages exists.1 Differential diagnosis of brown tumors includes giant cell reparative granuloma and giant cell tumor (GCT) of the bone.

The case of a patient with PHP due to a parathyroid adenoma with brown tumors mimicking a metastatic GCT is reported.

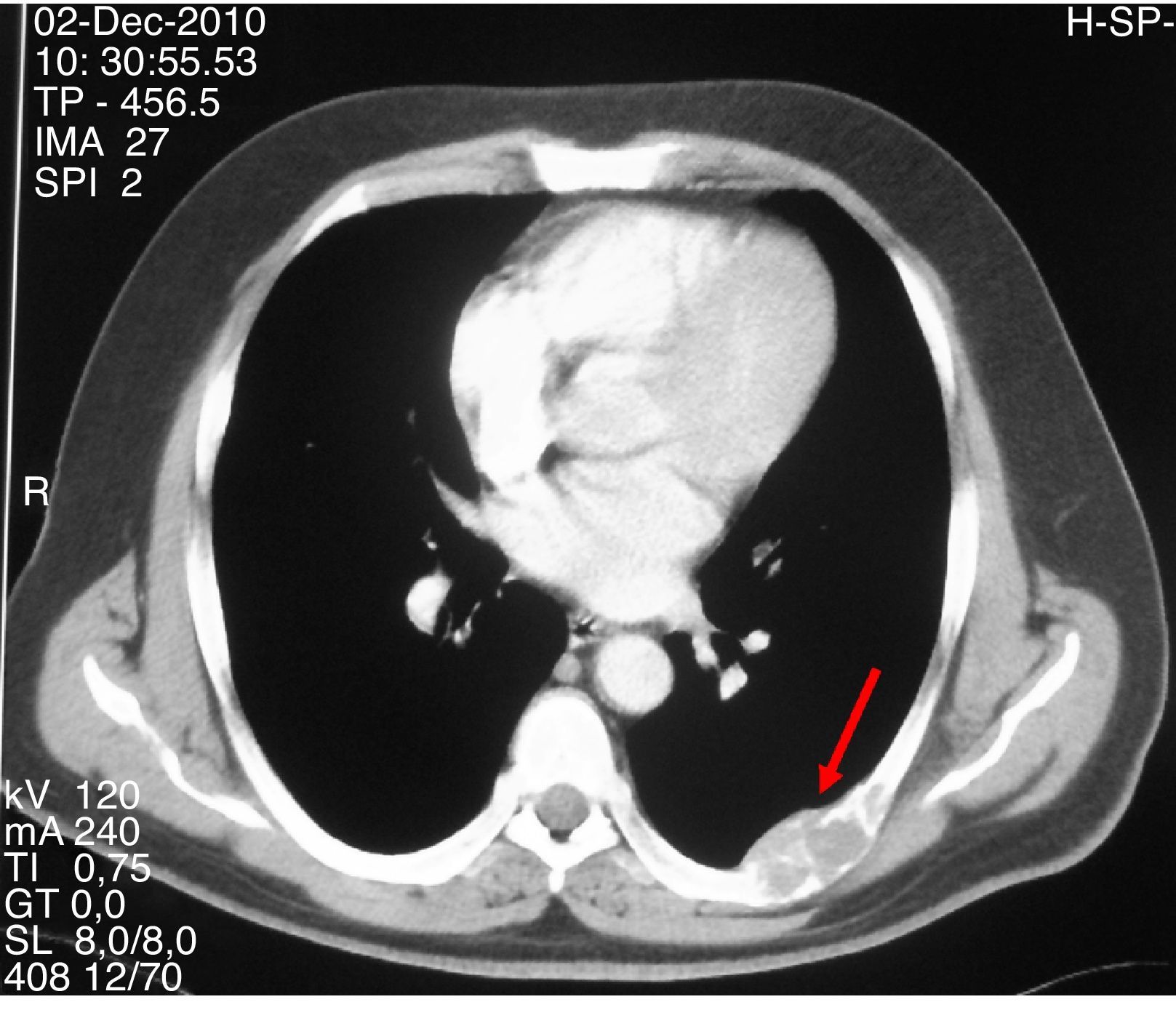

A 47-year-old first attended the orthopedic surgery department of a hospital in Castile-La Mancha in May 2008 complaining of pain in the hip and left hand not associated with prior trauma. The patient reported a personal history of dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, grade I obesity, and renal colic with calcium oxalate stones. His family history included two daughters who had been diagnosed and undergone surgery for PHP due to adenoma. Plain X-ray of the hip and hand showed a polylobulated cystic image that inflated and thinned cortical bone in the third left metacarpal bone and supra-acetabular and left ilioischiopubic ramus lytic lesions. A CT scan of the pelvis (November 2008) showed large lesions in the iliac ala, ischium, left pubic ramus, and right sacral wing and femoral neck. Based on these findings, in July and September 2009 the patient underwent surgery consisting of curettage and filling with both an autologous graft and bone substitutes of the third left metacarpal bone and the left supra-acetabular lesion. The pathological laboratory reported a GCT. Subsequent controls with CT and MRI of the chest and pelvis revealed the enlargement of polylobulated and expansive lytic lesions in the pelvis (Fig. 1), sacrum, right femoral neck, and L5, with the appearance of a new lesion in the right femoral head and left seventh costal arch (Fig. 2). These changes were attributed to metastatic tumor progression. Because of persistent pain that totally prevented ambulation, the patient was referred to the bone tumor unit of Hospital Universitario La Paz, where a review of pathological samples led to the conclusion that the bone lesions were highly suggestive of giant cell reparative granulomas and histologically indistinguishable from brown tumors. Hyperparathyroidism was therefore ruled out. In November 2010, the patient was referred to the endocrinology department, where additional laboratory tests provided the following results: total calcium 14mg/dL, corrected calcium 13.2mg/dL, ionic calcium 1.72mmol/L, phosphate 1.9mg/dL, magnesium 1.86mg/dL, urinary calcium 968.60mg/24h, creatinine 0.55mg/dL, iPTH 535pg/mL, vitamin D 13ng/mL. Total body CT showed a nodule 1.5cm in diameter in the theoretical location of the right parathyroid gland, and a parathyroid scan with 20mCi of TC 99-sestamibi revealed findings consistent with right hyperfunctioning parathyroid adenoma. In addition, the presence of an associated pheochromocytoma was ruled out based on both biochemistry and morphology. Right parathyroidectomy was performed, and an intraoperative biopsy was reported as a parathyroid adenoma. The final histopathological study confirmed the presence of a parathyroid adenoma 4.5g in weight and 2.2cm×2cm×1.9cm in size.

After surgery, the patient experienced symptomatic hypocalcemia which required treatment with calcitriol and calcium, which has been continued to date. He continues to be followed up at the endocrinology department, reports significant symptomatic improvement and is able to walk with crutches. A genetic study found no mutations in the MEN-1 gene.

GCT is a highly vascularized tumor which is found in the metaphyses or epiphyses of long bones or in the pelvis, sacrum, or vertebrae.2 The radiographic and histological appearance of brown tumors typical of OFC may closely mimic a GCT, as occurred in our patient, and differentiation should be made based on clinical signs and laboratory results (iPTH). Some of the authors3,4 have reported cases of OFC in which secondary metastatic bone disease was initially suspected based on clinical signs and radiographic images. In our patient, however, diagnosis of a metastatic primary bone tumor had been based on histological findings, while the family history, not reported in the above cases, was consistent with PHP.

On the other hand, vitamin D deficiency is often detected in patients with PHP and is3,5 associated with exacerbation of the biochemical and phenotypical presentation of the disease (higher serum PTH levels, large parathyroid adenomas, and greater risk of fracture), which may have contributed to the florid clinical picture of our patient.

Familial forms of hyperparathyroidism are known to be uncommon (5%), and their most frequent causes include multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) type 1 and 2A syndromes, hyperparathyroidism-jaw tumor (HPT-JT) syndrome, and familial isolated hyperparathyroidism (FIHP).6 In MEN 1, hyperparathyroidism is the earliest and most common presentation (>90%), while in MEN 2A it occurs late and has a low penetrance. Although the genetic study for MEN 1 was negative in our patient, it should be noted that a false negative result may occur in up to 30% of the tested cases as the result of mutation patterns involving different gene regions or mutations in as yet unknown genes affecting menin transcription or action.7 This, together with the probable asynchronous occurrence of different aspects of MEN-1, makes continuous monitoring necessary. MEN 2A is unlikely in the absence of thyroid neoplastic involvement or pheochromocytoma. Differential diagnosis should also include HPT-JT because of the scale of bone involvement and the large size of the adenoma. The final finding of a parathyroid carcinoma would have supported this diagnosis, because of its frequent occurrence in HPT-JT.8 However, the absence of mandibular or maxillary fibro-osseous lesions and renal lesions made this unlikely. Finally, although FIHP may represent in some cases a variant of other hyperparathyroid syndromes, the possibility that mutations located in as yet unidentified loci other than those reported in MEN 1 and 2 and in HPT-JT may cause this syndrome cannot be ruled out.

The interest of the reported case lies in the fact that it illustrates the importance of assessing phosphorus and calcium metabolism and parathyroid function in all the patients with bone lesions, of suspecting a potential PHP if suggestive lesions exist, and of searching a probable underlying genetic component through a detailed family and personal history.

Please, cite this article as: Parra Ramírez PA, et al. Hiperparatiroidismo primario con osteítis fibrosa quística simulando una neoplasia ósea maligna. Endocrinol Nutr. 2013;60:96–109.