Black adrenal adenomas are adrenal cortical tumors that are black or dark brown on cut sections. The first case of black adrenal adenoma was reported in 1938.1 Autopsy studies published in the early 1970s suggest that the pigments in black adrenal adenomas are made of lipofuscin, a lysosomal material, and that these tumors are common autopsy findings (10% on random adrenal sections and 37% on fine sections) but do not secrete hormones.2 In 1973, two of us (G.D.B. and R.R.E.) cared for and studied a patient with a black adrenal adenoma that caused ACTH-independent Cushing's syndrome. We here describe the case and discuss it in historical background and in light of the literature on this topic in the last 40 years.

A 42-year-old Caucasian female had been well until 1966 when she developed hypertension, edema, and hyperglycemia during her third pregnancy. In 1969, she developed right femoral head aseptic necrosis. She also noted a 40-pound weight gain, rounding of face, the development of a dorsal fat pad, ruddy complexion, facial hair, weakness, easy fatigability, emotional liability, irregular menses, and easy bruising. In January 1973, she was seen at Harbor General Hospital (now Harbor-UCLA Medical Center). She denied skin darkening, exogenous steroid ingestion, or family history of endocrine diseases. Physical examination revealed a hypertensive, Cushingoid female. Endocrine evaluation revealed absence of suppression of plasma or urinary 17-hydroxysteroids by both low (2mg) and high (8 and 12mg) doses of dexamethasone administration. Her plasma 17-hydroxysteroids failed to increase after metopirone (more commonly called “metyrapone” now) administration or synthetic ACTH (Cortrosyn) infusion. ACTH-independent Cushing's syndrome was diagnosed and the presence of a functional adrenal lesion deemed probable. Adrenal androgen levels were not measured. The patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy through which the right adrenal gland was found to be grossly normal but the left adrenal to harbor a mass. A left adrenalectomy was performed. Her post-operative course was uncomplicated and the Cushingoid features gradually regressed in the ensuing 2 months. She developed adrenal insufficiency postoperatively and was treated with corticosteroids with tapered doses.

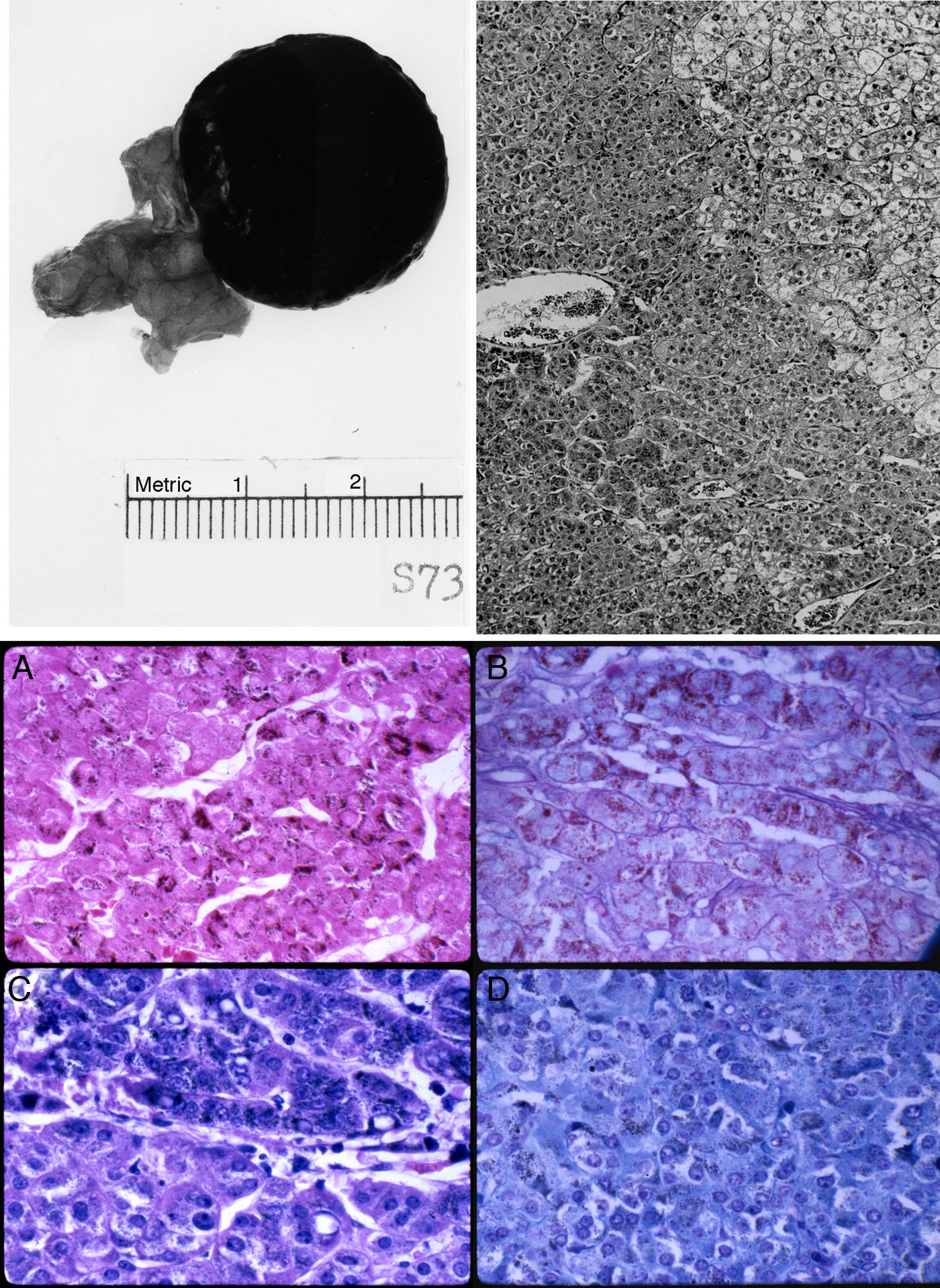

The left adrenal mass appeared well circumscribed and measured 3×2cm (Fig. 1). The tumor was homogeneously dark brown to black throughout (Fig. 1, top left). Microscopically, the mass consisted of large, polygonal, eosinophilic cells resembling those of the zona reticularis. The tumor cells abutted directly on but did not invade into the non-pigmented cells of the gland (Fig. 1, top right). The majority of these cells contained heavy deposits of golden brown, slightly refractile, granular, pigments which were localized predominantly at the cell periphery. The pigments were visible also with Congo Red, Gomori iron, and in even in unstained slides (Fig. 1, bottom). It reacted weakly with Sudan black and negatively with acid fast stains. Fontana stain was strongly positive and the pigment assumed a reddish coloration with the periodic acid-Schiff's technique. The pigments appeared green with Giemsa stain and greenish blue with Luxol fast blue stain, thus indicating that they consisted of lipofuscin. Mitotic figures were very rare. The tumor cells did not exhibit nuclear atypia, necrosis, or atypical mitotic figures.

Top left: gross photograph of the black adrenal adenoma with atrophic adrenal seen in the adipose tissue to the left. Top right: margin of zona reticularis with pigmented tumor cells below and to the left. Hematoxylin and eosin. Magnification, 120×. Bottom: lipofuscin pigments as stained by (A) Fontana; (B) Alcian blue-PAS; (C) Giemsa; and (D) Luxol fast blue. Magnification, 480×.

To assess how frequent the black adrenal adenoma is, we examined our pathology database between 1998 and 2014. One hundred and fourteen adrenal cortical tumors were found. The average age of patients was 53 years (range 23–70). Forty-one of the adenomas were aldosterone-secreting, 23 cortisol-secreting, 1 androgen-secreting, and 49 nonfunctional. The average adenoma size was 3.1cm (range 0.2–27). Twenty-three of the adenomas were ≤1.5 cm and 91 larger. The tumor color ranged from yellow, orange, tan, red, to brown. None of the 114 adenomas was predominantly black or dark brown.

Our study of the frequency of black adrenal adenoma here and the work of others in the last 40 years advance our understanding of this interesting tumor. Black adrenal adenomas may be more common on post-mortem adrenals but they are certainly rare in surgical adrenal samples. In our own series of 115 adrenal cortical tumors from surgical adrenal samples, not a single black adrenal adenoma was encountered. Although the incidence of black adrenal adenomas has not been formally addressed in other surgical series, the mostly single-case reports of this unique-colored tumor even recently suggest that they are indeed rare in surgical adrenal samples.3 The discrepancy between the high frequency of incidental black adrenal adenomas in autopsy findings and their exceptionally low incidence in surgical series may be due to the small size and non-functional nature of the adenomas which avoid the surgery in spite of the tumors’ radiological features. Most of black adrenal adenomas, like in this case, cause ACTH-independent Cushing's syndrome, some cause primary hyperaldosteronism, and a few even result in masculinization.3–5 Less frequently reported are nonfunctional black adrenal adenomas which present as incidentalomas.6 With the introduction of CT, MRI, and FDG-PET, the imaging characteristics of adrenal adenomas in general and the distinct imaging features of black adrenal adenomas in particular have now been well described. Unlike most other adrenal adenomas, the black ones exhibit high Hounsfield units (>30) on CT, high T2 signal and lack of drop of signal on out-of-phase imaging on MRI, and high standard uptake value (higher than that of liver) on FDG-PET, which all indicate less tumor lipid content but higher tissue density and blood supply, features suspicious of pheochromocytoma, interstitial tumors, and malignancy.6–8 Furthermore, the black adrenal adenomas are often not visualized by radiocholesterol scintigraphy.9,10 Biologically, however, the black adrenal adenomas are benign without histological evidence of aggressiveness or invasiveness, as our patient's tumor. Black adrenal adenomas should now be considered as one subtype of adrenal adenomas with atypical imaging characteristics. The clinical significance of lipofuscin pigments in black adrenal adenomas remains unclear.11 Black adrenal adenomas are unilateral, solitary adrenal cortical tumors; they are in contrast to primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease (PPNAD) which involves diffuse nodular enlargement of both adrenal glands.12 PPNAD can occur as part of the Carney complex and is associated with a genetic defect, PRKAR1A mutation. The pigments in PPNAD are also due to lipofuscin. Patients with PPNAD can exhibit a paradoxical increase of cortisol levels after administration of dexamethasone.

In summary, black adrenal adenomas appear to derive from the zona reticularis and their black color is due to lysosomal lipofuscin. Clinically very rare tumors, they mainly present as Cushing's syndrome or other syndromes of adrenocortical hormone hypersecretion. Although biologically benign, they exhibit atypical imaging characteristics suspicious of malignancy. The main difference between black adrenal adenomas and other adrenal cortical tumors is just the appearance to the naked or aided eye.