To ascertain how health care for pregnant women with gestational diabetes (GD) and pregestational diabetes (PGD) is organized, and to estimate the number of Pregnancy and Diabetes Units (PDUs) in Spain in 2013.

Material and methodsThe Spanish Group of Diabetes and Pregnancy (GEDE) developed and agreed on a questionnaire based on the recommendations of the group. The questionnaire was sent to members of the Spanish Society of Diabetes and the Spanish Society of Endocrinology and Nutrition.

ResultsEighty-seven questionnaires were received from 81 hospitals, 4 outpatient specialty centers, and 2 primary healthcare centers, which accounted for 51% of the Spanish population and for 39% of births in 2013. GD was mainly diagnosed based on GEDE recommendations (98%), and less than 50% of women were reevaluated after delivery in primary care. Fourteen (26%) of the 53 centers identified as PDUs corresponded to a minimal model. Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) therapy was not available in 30% of centers, and 13% of hospitals had no preconceptional clinics. No nurse support was available in 20% of centers.

ConclusionsCare of women with PGD has a fair coverage with PDU, but significant deficits still exist, for instance, in preconception clinic and CSII. However, organization of care for women with GD appears to be adequate. There are aspects in need of improvement such as integration of diabetes educators and coordination with primary care for postpartum reclassification.

Conocer la organización de la atención sanitaria de las gestantes con diabetes gestacional (DG) y diabetes pregestacional, y estimar el número de unidades de diabetes y gestación en España en 2013.

Material y métodosEl Grupo Español de Diabetes y Embarazo elaboró y consensuó un cuestionario basándose en las recomendaciones de la guía asistencial del grupo. El cuestionario fue enviado a los miembros de la Sociedad Española de Diabetes y de la Sociedad Española de Endocrinología y Nutrición.

ResultadosSe recibieron 87 cuestionarios (81 hospitales, 4 centros de especialidades, 2 centros de salud), que representaban al 51% de la población censada en España y el 39% de los partos atendidos en el año 2013. El diagnóstico de la DG se hizo mayoritariamente siguiendo recomendaciones del Grupo Español de Diabetes y Embarazo (98%), y en menos del 50% de los casos la reclasificación posparto se realizó en atención primaria. De los 53 centros considerados unidades de diabetes y gestación 14 (26%) respondían a un modelo mínimo. El 13% de los centros no realizan clínica preconcepcional, y un 30% no contaban con terapia con infusión subcutánea continua de insulina. En un 20% de los centros la asistencia la realizaba el facultativo sin apoyo de enfermería.

ConclusionesLa asistencia de las mujeres gestantes con diabetes pregestacional tiene una cobertura intermedia con carencias importantes, como clínica preconcepcional e infusión subcutánea continua de insulina, mientras que en las mujeres con DG se puede considerar suficiente. Existen aspectos a mejorar, como la integración de la educadora en diabetes y la coordinación con atención primaria para la reclasificación posparto.

Diabetes mellitus is the endocrine-metabolic disease that most commonly complicates pregnancy, either as gestational diabetes (GD) or as pregestational diabetes (PGD). The significance of the disease stems from both its prevalence and the negative implications for the mother, fetus, and newborn,1 despite the fact that the associated complications have decreased in the past four decades.2 The treatment of GD is associated with a decreased frequency of preeclampsia, shoulder dystocia, and macrosomia.3 On the other hand, the planning of pregnancy and preconception controls in PGD have been associated with a decreased frequency of congenital malformations, the risk of preterm delivery, and perinatal mortality.4,5

The objectives, management, and resources (both material and human) required for an adequate metabolic, obstetric, and perinatal control of pregnancies complicated with diabetes are regularly reviewed and published in the guidelines for care of the main scientific bodies.6–9 The Spanish Group on Diabetes and Pregnancy (GEDE) of the Spanish Diabetes Society (SED) recently updated its guidelines regarding patient care, adapting the scientific evidence available to the currently existing working environment.1 In any health system, understanding the actual situation and the level of care provided to pregnant women with diabetes is essential in order to achieve adequate maternal and fetal outcomes, to be able to detect deficiencies, and to propose improvements.

In this regard, the GEDE wanted to know as much as possible regarding the organization of care for pregnancies complicated by diabetes, the services provided, the material and human resources available and, especially, the diabetological care available. An attempt was made to estimate the number and characteristics of diabetes and pregnancy units (DPUs) and the population they cover.

Patients and methodsThis observational, retrospective, cross-sectional study was designed to evaluate how care is provided to women with pregnancy complicated by diabetes in Spain, and to collect data on care activity during 2013. The study was conducted by distributing an online questionnaire to members of SED and the Spanish Society of Endocrinology and Nutrition (SEEN). The confidentiality of the demographic and personal data of the centers involved was preserved during the period of the study.

The questionnaire was specifically designed with the study in mind. A preliminary questionnaire prepared by two of the authors (J.A. Rubio and M. Ontañon), which included the practical aspects of the GEDE guidelines,1 was discussed and modified at an initial meeting, and subsequently through online contacts until agreement was reached on a final version. The first part of the questionnaire addressed sociodemographic and center data, while the second part contained 28 questions. Most of the questions required the selection of one answer from multiple alternatives, and there were no open questions (see supplemental material). To limit bias, the questions were carefully written to avoid influencing the answers to the survey.

Dissemination of the questionnaireThe intention was to send the questionnaire to all physicians responsible for the care of women with pregnancy complicated by diabetes. With this aim in mind, the SED and SEEN were contacted, and these organizations sent to all their active members, by electronic mail, an invitation to participate in the study along with an electronic link to the website where the questionnaire could be found. The email specified that only one questionnaire per center should be completed, and that it was important to answer regardless of the complexity of care and of how it was being provided to pregnant women with diabetes. It was sent in October 2014 to all SED members, and in December 2014 to SEEN members. The questionnaire was closed on February 15, 2015. The authors did not make direct contact with any potential responder.

Data analysisPopulation coverage was estimated as the percentage of the overall response of the responding centers. For this purpose, the whole reference population cared for by the centers in each autonomous community was divided by the census population of both the community and of Spain in 2013.10 This methodology was also used to estimate the coverage of deliveries by the responding centers.11 Data on the reference population of the hospitals and the deliveries attended were provided by the surveyed physicians and verified, or were collected from the annual reports or websites of the hospitals included in the survey.

The question analyzing the existence of a DPU at the hospital was: is there at your hospital an outpatient clinic or unit that cares for most pregnant women with diabetes? A hospital was considered to have a DPU if two criteria were met: (1) there was at least one specialist each in endocrinology and obstetrics; and (2) the hospital had a preconception diabetes clinic.

DPU complexity was then estimated based on the following predefined criteria: (1) a minimum model (MM): only the two prior criteria were met; (2) an intermediate model (IM): MM+a specific education nurse for monitoring pregnant women with diabetes and the availability of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) therapy; (3) a model of excellence (ME): IM+all three indicators of excellence (the participation in training of professionals, quality control at the unit, and participation in research projects [items 26–28]).

The percentage of the population and the deliveries covered by DPUs throughout Spain was estimated using the same methods as used for the previously described analysis of population representativeness.

To analyze the number of women with GD and PGD attending each hospital, the upper extreme outliers (values that differed from the third quartile by more than three times the interquartile range) were discarded. For hospitals caring for all women with GD, GD prevalence was estimated as the ratio between the number of women with GD seen at the hospital in 2013 and the number of deliveries in that same year. It was assessed whether the frequency of insulin therapy for GD by hospital varied depending on some care aspects (items 1, 2, 4, 12, 13, and 14) and whether these differences persisted as a function of the number of women with GD seen by hospital. To analyze data on PGD, only hospitals and specialized centers were considered. Type 1 DM (T1DM) vs type 2 DM (T2DM) ratios by center were obtained.

Quantitative data were displayed as median (P25-P75) because they were not normally distributed (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test) and qualitative data as absolute value and percentage (%). A Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparative analysis of the frequency of insulin therapy between the groups. A two-sided value of p<0.05 was considered significant. Microsoft® Office Excel 2007 and statistical software Analyze-it for Microsoft Excel (version 2.20) were used.

ResultsQuestionnaires completed and population representativenessEighty-seven questionnaires were received from 81 hospitals, four specialized centers, and two healthcare centers. Of these, 70, 8, and 9 were public, contracted, and private health centers respectively. The questionnaires were most commonly completed by endocrinologists (78, 90%), and to a lesser extent by multidisciplinary teams, an endocrinologist-pediatrician, an endocrinologist-obstetrician, or professionals from independent specialties such as internal medicine and obstetrics.

Seventy-three centers had a total reference population of 23,684,467 inhabitants assigned, that is, 51% of the census population in Spain (as of January 1, 2014). Deliveries were done at 74 centers, but only data from 69 centers were available. The centers cared for a total of 164,108 deliveries, or 39% of the deliveries in Spain during 2013. No questionnaires were received from the community of Extremadura or the towns of Ceuta and Melilla, and these areas are therefore not represented.

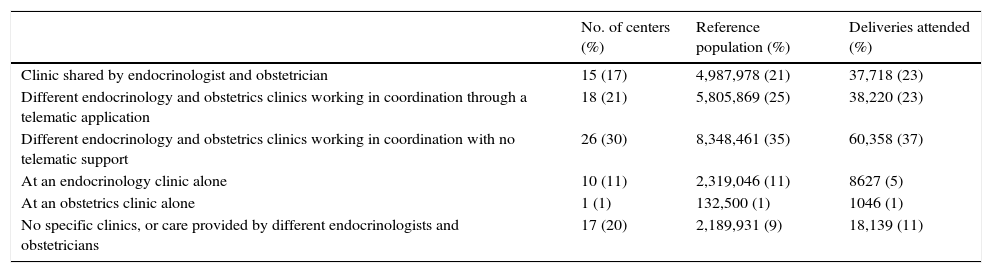

Organization of the care of pregnant women with diabetesWhen asked: is there an outpatient clinic or a unit that cares for most pregnant women with diabetes at your hospital?, 59 (68%) hospitals answered that they had endocrinologists and obstetricians for care, but that there were different types of organization, as shown in Table 1.

Distribution of the organization of care for pregnant women with diabetes.

| No. of centers (%) | Reference population (%) | Deliveries attended (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinic shared by endocrinologist and obstetrician | 15 (17) | 4,987,978 (21) | 37,718 (23) |

| Different endocrinology and obstetrics clinics working in coordination through a telematic application | 18 (21) | 5,805,869 (25) | 38,220 (23) |

| Different endocrinology and obstetrics clinics working in coordination with no telematic support | 26 (30) | 8,348,461 (35) | 60,358 (37) |

| At an endocrinology clinic alone | 10 (11) | 2,319,046 (11) | 8627 (5) |

| At an obstetrics clinic alone | 1 (1) | 132,500 (1) | 1046 (1) |

| No specific clinics, or care provided by different endocrinologists and obstetricians | 17 (20) | 2,189,931 (9) | 18,139 (11) |

First column: number of centers and percentage of all centers, n=87. Second column: sum of the reference population of centers giving the same answer and percentage of the population of responding centers, n=23,684,467 inhabitants. Third column: sum of the deliveries attended at centers giving the same answer and percentage of all deliveries at the responding centers, n=164,108 deliveries.

Sixty-three (72%) centers answered that they had diabetes educators specifically caring for pregnant women (one nurse at 29 hospitals [48%], 2 at 25 [41%], and 3 at 7 [11%]). A nurse was available for educating patients with GD and PGD in 88% and 76% of hospitals, respectively, and for patient monitoring in 70% and 56% respectively. Twenty-four hospitals (28%) had some type of telematic application connecting pregnant patients and the team in charge of their monitoring.

Diagnosis, control, and reassessment of gestational diabetesIn the first trimester, screening for GD was only performed in the risk groups at 76 hospitals (87%), while universal screening was performed in the second trimester at 86 hospitals (99%). The screening most commonly consisted of blood glucose measurement after the administration of 50g of glucose, with a cut-off point of 140mg/dL (7.8mmol/L), used at 85 hospitals (98%). The National Diabetes Data Group criteria after an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) of 100g were used at 77 centers (91%), and the Carpenter and Coustan criteria at 8 centers (9%). One center used the criteria of the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Group.

Seventy-one centers (82%) monitored all women diagnosed with GD in their areas, while 12 centers (14%) only monitored those with greater complexity, with the support of centers of excellence and specialties. Monitoring was done by both the physician and educator in 56 centers (64%), by educators following a protocol in 14 centers (16%), and by the physician alone in 17 centers (20%).

Diabetes care was preferentially performed by a specific professional in 64 centers (74%), while obstetric care was provided by a specific professional in 45 centers (52%).

GD monitoring and post-partum evaluation were usually performed at the same center (55, 63%), and less commonly in primary care (31, 36%). The most usual form of reassessment was an OGTT using 75g of glucose (41 centers, 48%), followed by an OGTT combined with HbA1c measurement (37 centers, 43%).

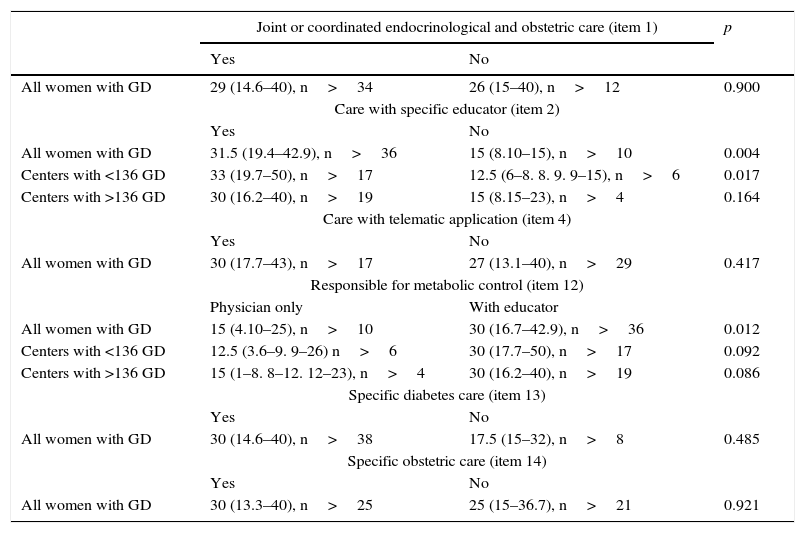

Prevalence and frequency of insulin therapy in gestational diabetesA total of 10,676 women with GD were evaluated, with a median of 136 (71.5–250) by study center (n=59) and an 8.2% prevalence of GD (6.5%-10%) (n=40). Insulin therapy was administered to 28% of patients (15%–40%) (n=46). Table 2 analyzes the frequency of insulin therapy by type of care. Insulin therapy was more common at centers with a specific educator for GD control who was involved in monitoring, as compared to centers where monitoring was performed by physicians only. These differences continued after analysis depending on the number of women attending the centers, using the median as the cut-off point.

Frequency of insulin therapy in women with GD by type of care.*.

| Joint or coordinated endocrinological and obstetric care (item 1) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| All women with GD | 29 (14.6–40), n>34 | 26 (15–40), n>12 | 0.900 |

| Care with specific educator (item 2) | |||

| Yes | No | ||

| All women with GD | 31.5 (19.4–42.9), n>36 | 15 (8.10–15), n>10 | 0.004 |

| Centers with <136 GD | 33 (19.7–50), n>17 | 12.5 (6–8. 8. 9. 9–15), n>6 | 0.017 |

| Centers with >136 GD | 30 (16.2–40), n>19 | 15 (8.15–23), n>4 | 0.164 |

| Care with telematic application (item 4) | |||

| Yes | No | ||

| All women with GD | 30 (17.7–43), n>17 | 27 (13.1–40), n>29 | 0.417 |

| Responsible for metabolic control (item 12) | |||

| Physician only | With educator | ||

| All women with GD | 15 (4.10–25), n>10 | 30 (16.7–42.9), n>36 | 0.012 |

| Centers with <136 GD | 12.5 (3.6–9. 9–26) n>6 | 30 (17.7–50), n>17 | 0.092 |

| Centers with >136 GD | 15 (1–8. 8–12. 12–23), n>4 | 30 (16.2–40), n>19 | 0.086 |

| Specific diabetes care (item 13) | |||

| Yes | No | ||

| All women with GD | 30 (14.6–40), n>38 | 17.5 (15–32), n>8 | 0.485 |

| Specific obstetric care (item 14) | |||

| Yes | No | ||

| All women with GD | 30 (13.3–40), n>25 | 25 (15–36.7), n>21 | 0.921 |

Data are percentages, median (P25–P75]. Calculation was only performed for centers doing total monitoring of women.

At specialized centers (n=85), the preconception visit was performed at individual consulting rooms by different professionals, endocrinologists or obstetricians, in 54 centers (63.5%) and at the same unit or consulting room by both specialists in 20 centers (23.5%). No preconception visits were performed in 11 centers (13%). Specific physicians were in charge of diabetes and obstetric care in 59 (69%) and 51 (60%) centers respectively. CSII, a blood glucose meter, and a bolus calculator were available and used if required in 59 (69.4%), 43 (50.5%), and 67 (78.8%) centers respectively. In 57 centers (67%), post-partum monitoring was performed at the same clinic as used during pregnancy, while in 28 centers (33%) patients were referred to the physician responsible for monitoring before pregnancy.

Types of pregestational diabetesFifty-two centers reported care for 1161 females: 633 (54.5%) with T1DM, 485 (41.7%) with T2DM, and 43 (3.7%) with other types of DM, with a mean overall T1DM/T2DM ratio of 1.3. Forty-four centers caring for T1DM and T2DM had a T1DM/T2DM ratio of 1 (0.5–2.1).

Indicators of excellence in diabetes and pregnancy careThree aspects were assessed (items 27–29): participation in professional training and retraining in 53 centers (62%), quality controls promoting action protocols and the keeping of registries in 46 (54%), and involvement in research projects or multicenter studies in 30 (35%) centers.

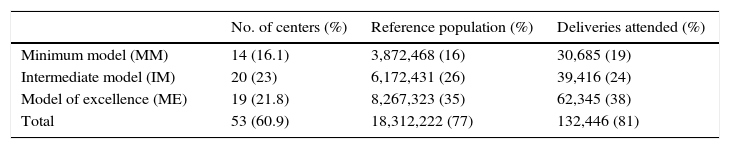

Approximation to diabetes and pregnancy unitsFifty-three centers met the criteria required for being designated as DPUs. These covered 77% of the reference population of the study centers and 81% of deliveries occurring at the responding centers. Table 3 shows the distribution and estimation of the population covered by centers of the MM, IM, and ME models. Thirteen of the 14 MM centers were hospitals.

Diabetes and pregnancy units grouped by model.

| No. of centers (%) | Reference population (%) | Deliveries attended (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum model (MM) | 14 (16.1) | 3,872,468 (16) | 30,685 (19) |

| Intermediate model (IM) | 20 (23) | 6,172,431 (26) | 39,416 (24) |

| Model of excellence (ME) | 19 (21.8) | 8,267,323 (35) | 62,345 (38) |

| Total | 53 (60.9) | 18,312,222 (77) | 132,446 (81) |

First column: distribution and percentage of all responding centers, n=87. Second column: sum of the reference population of centers with DPUs and percentage of the population of responding centers, n=23,684,467 inhabitants. Third column: sum of the deliveries attended at centers with DPUs and percentage of all deliveries at the responding centers, n=164,108 deliveries. ME: IM+all three indicators of excellence (participation in the training of professionals, quality control at the unit, or participation in research projects); IM: MM+specific education nurse for monitoring pregnant women with diabetes and availability of CSII; MM: (1) at least one specialist each in endocrinology and obstetrics available; and (2) a preconception diabetes clinic.

This study is the first approximation in Spain to the actual care currently being provided to pregnant women with diabetes, and shows an intermediate coverage with DPUs for the care of PGD and an adequate coverage for GD. It is estimated that 3 out of every 5 pregnant women with PGD were seen at DPUs with resources providing an adequate quality of care, but that 2 out of every 5 women either had no access to a DPU, or the DPU did not have the minimum resources to optimize blood glucose control, such as access to CSII therapy or a specific education nurse for the control of gestational diabetes.

Most centers responding, 81 out of 87, were hospitals, which is where women with GD and PGD have traditionally been cared for in Spain. Only 4 centers of excellence and specialties answered the survey, which reflects the hierarchization of care in Spain, where those centers refer most women with GD and PGD to their reference hospital.

While the number of centers surveyed was low as compared to the total number of centers of the NHS, 498 general or maternity hospitals,12 they covered 51% of the 2013 Spanish population census and accounted for 39% of deliveries attended during that year. They are, in our view, a representative sample as regards current health care of these diseases, although with a certain bias toward centers with greater population coverage and, consequently, with probably more resources.

The screening of the population at risk in the first trimester, diagnosis in two steps, and the preferential use of the National Diabetes Data Group criteria for GD show that most centers have decided to continue using the criteria recommended by the GEDE in 200613 and confirmed in 2015,1 and have not implemented the recommendations of the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Group.14 The survey shows a consistent use of GEDE recommendations for the diagnosis of GD, with no differences in criteria between the different centers. This is important, because it avoids significant differences in prevalence depending on the area, which may have an impact on maternal and fetal outcomes, as seen in other countries.15

The median GD prevalence at the centers that reported monitoring of the whole population was 8.2%, although 25% of the centers did not reach 6.6%. These fluctuations may be attributed to population differences, defects in detection, or the loss of cases in the population area. These data agree with those reported by other European centers16 and a multicenter Spanish study.17 Insulin therapy was administered to 28% of patients, with a very wide percentile distribution between the centers. The survey shows differences in the severity of metabolic impairment between the centers, and probably in standard clinical practice also. This latter possibility is supported by the greater frequency of insulin therapy in models in which nursing was involved in disease monitoring, showing once again the barrier that insulin therapy represents for pregnant women in everyday life,18 and the significance of the role of specialized diabetes education for achieving adequate control.19 A striking finding in this study was that, in 20% of the centers, metabolic monitoring was performed by a physician alone, with no support from the nursing staff. This contrasts with the recommendations in the main guidelines,6–9 based on the fact that such an approach is not associated with better maternal and fetal outcomes.20

Post-partum reassessment was performed with almost the same frequency using OGTT (75g) alone or combining OGTT and HbA1c measurement, in contrast to recommendations by the GEDE1 and most guidelines,7–9 which advise the use of OGTT with 75g for reclassification. The fact that post-partum reclassification and monitoring were mostly performed at hospitals rather than primary care, as recommended,1,21 appears to suggest both a lack of coordination and a lack of joint action protocols between care levels, with a resultant misuse of resources. This may also be explained by the traditionally insufficient involvement of primary care teams in pregnancy control.22 Since a diagnosis of GD identifies a group of women at a high risk of DM requiring preventive actions, we think that action protocols are needed to coordinate post-partum monitoring with primary care.

A relevant finding in this study was the significant deficiencies in the portfolio of services for patients with PGD at some centers. Thus, 13% of centers had no preconception clinic, and 30% did not have CSII as an option available for improving control.1,6–9 T1DM was predominant, but there was a great heterogeneity, in agreement with reports from other population studies.23

The classification of DPUs into 3 models, MM, IM, and ME, allowed for an approach to their level of complexity. Based on the reference population and/or deliveries attended, it was estimated that 3 out of every 5 women with PGD received care at IM and ME. By contrast, 2 out of every 5 had no DPU or had a MM DPU, which, in our view, is clearly inadequate for women with PGD. The added value provided by multidisciplinary teams in the management of some diseases24 is particularly evident in PGD.6–9 Aspects such as the type of center and team experience have a direct impact on control and neonatal outcomes.25 By contrast, women with GD were seen at DPUs in basically a hospital setting, with less regard being paid to the complexity of their management, and thus, possibly with an inadequate use of the available resources.

It should finally be noted that only 28% of the centers used telemedicine for monitoring pregnant women with diabetes, despite the potential savings in medical visits and the improvement of the quality of life in women with both GD and PGD, although in GD improvement has only been reported in metabolic control, but not in other maternal and fetal outcomes.26,27 The conclusions of such studies are limited by the few studies available which have analyzed this type of care and the low number of women enrolled, particularly with PGD and specifically with T1DM.28 The implementation of telemedicine for monitoring pregnant women with diabetes, as well as further research, is, therefore, required.

This study has a number of limitations. First of all, evaluation of the actual care provided to pregnant women with DM was partial, because it mainly focused on endocrine control, only limited attention being paid to obstetric care. As the survey was distributed through the SED and SEEN, it may not have reached DPUs managed by physicians who are not active members of these societies and who had therefore no access to the channels through which the questionnaire was disseminated. Second, the estimation of the population covered by the DPUs is based on the premise that 50% of the population not represented in the survey receives the same care as that provided in the responding centers. If this premise were not assumed, the deficiencies detected in care would be much greater.

On the other hand, the strengths of this study include the wide dissemination of the survey throughout Spain, as well as the value shown by this information collection tool as regards reliability as compared to other methods (telephone interview or ordinary post).29

It may be concluded from this study that the care provided for pregnant women with PGD has an intermediate coverage, with significant deficiencies in aspects such as preconception clinic and CSII, while the care provided for women with GD may be considered adequate. Aspects in need of improvement include the integration of diabetes educators and coordination with primary care for post-partum reclassification. Finally, most centers adhered to the criteria proposed by the GEDE for the diagnosis of GD.

Conflicts of interestThe authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

We thank all members of SED and SEEN for their unselfish participation by completing this questionnaire. We also thank the boards of both societies for facilitating the dissemination of the questionnaire.

Domingo Acosta, Hospital U. Virgen del Rocío, Seville; Montserrat Balsells, Hospital Mutua de Terrassa, Barcelona; Mónica Ballesteros, Hospital U. Joan XXIII, Tarragona; María Orosia Bandres, Hospital Royo Villanova, Saragossa; José Luis Bartha, Hospital U. La Paz, Madrid; Jordi Bellart, Hospital Clínico, Barcelona; Ana Isabel Chico, Hospital Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona; Mercedes Codina, Hospital U. Son Espases, Palma de Majorca; Rosa Corcoy, Hospital Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona; Alicia Cortázar, Hospital de Cruces, Baracaldo, Biscay; Sergio Donnay, Hospital U. Fundación Alcorcón, Madrid; María del Carmen Gómez, C.S. Velez-Norte, Málaga; Nieves Luisa González, Hospital U. de Canarias, Las Palmas; María del Mar Goya, Hospital U. Vall d’ Hebrón, Barcelona; Lucrecia Herranz, Hospital U. La Paz, Madrid; José López, Hospital Virgen de la Salud, Toledo; Patricia Martín, Hospital U. Fundación Alcorcón, Madrid; Ana Megía, Hospital U. Joan XXIII, Tarragona; Eduardo Moreno, Hospital U. Virgen del Rocío, Seville; Juan Mozas, Hospital Materno Virgen de las Nieves, Granada; Marta Ontañón, Hospital U. Príncipe de Asturias, Alcalá de Henares, Madrid; Verónica Perea, Hospital Mutua de Terrassa, Barcelona; José Antonio Rubio, Hospital U. Príncipe de Asturias, Alcalá Henares, Madrid; María Antonia Sancho, Hospital Clínico U. Lozano Blesa, Saragossa; Berta Soldevila, Hospital Germán Trias i Pujol, Badalona, Barcelona; Begoña Vega, Hospital Universitario Materno Infantil de Canarias, Las Palmas; Irene Vinagre, Hospital Clínico y Provincial de Barcelona, Barcelona.

Please cite this article as: Rubio JA, Ontañón M, Perea V, Megia A, en representación del Grupo Español de Diabetes y Embarazo. Asistencia sanitaria de la mujer gestante con diabetes en España: aproximación usando un cuestionario. Endocrinol Nutr. 2016;63:113–120.

The Grupo Español de Diabetes y Embarazo (GEDE) is a multidisciplinary group composed of members of the Sociedad Española de Diabetes (SED) and the Sociedad Española de Ginecología y Obstetricia (SEGO), whose current composition stated in Appendix A.