Some historical figures have suffered endocrine diseases. This review relates those whose diseases have been published in the scientific literature. It takes a biographical summary and describes the disease process in those considered most relevant by the nature of the disease or the importance of the figure in the Spanish and Latin American context: the Pharaoh Akhenaten, Maximinus I, Bodhidharma, Sancho I of Leon, William the Conqueror, Enrique IV of Castile, Henry VIII, Mary Tudor, Carlos II of Spain, Pio Pico, Pedro II of Brazil, Eisenhower and J. F. Kennedy.

Algunos personajes históricos han sufrido enfermedades endocrinológicas. Esta revisión relaciona aquellos cuyas enfermedades han sido publicadas en la literatura científica. Se realiza un breve apunte biográfico y se describe el proceso patológico en aquellos considerados más relevantes por la naturaleza de la enfermedad o la importancia del personaje en el ámbito español e iberoamericano: el faraón Akhenatón, Maximino I, Bodhidharma, Sancho I de León, Guillermo el Conquistador, Enrique IV de Castilla, Enrique VIII de Inglaterra, María Tudor, Carlos II de España, Pío Pico, Pedro II de Brasil, Eisenhower y J. F. Kennedy.

Endocrinology and Nutrition is a specialty of Medicine covering a wide number of fields related to the endocrine system, metabolism of immediate principles, vitamins and trace elements, and clinical nutrition, amongst others.1

Because of the high prevalence of some endocrine and nutritional diseases, it is hardly surprising that they have been suffered by historical figures. Specific diagnoses have been proposed for some public figures.

In addition to providing care, endocrinologists should play a teaching role for both undergraduates and graduates.1 Retrospective diagnosis of historical figures is an intellectual exercise that allows for a deeper understanding of differential diagnosis, and has a great interest in both academic and postgraduate teaching and continued training. It also serves to motivate students who start to study Endocrinology and Nutrition.

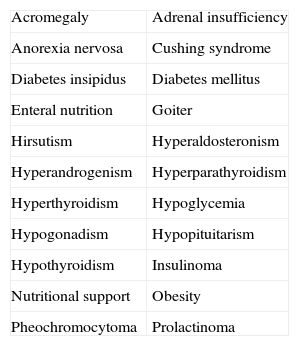

Materials and methodsA literature search was made in PubMed for historical figures reported to have suffered (or possibly suffered) an endocrinole or nutritional disease. For this, searches were made for articles which had indexed both the term “history” as medical subject heading–MeSH–and each of the terms listed in Table 1. Titles of articles retrieved were subsequently analyzed to choose those referring to a historical figure.

Medical subject headings used, together with “history”, in the literature search for this review.

| Acromegaly | Adrenal insufficiency |

| Anorexia nervosa | Cushing syndrome |

| Diabetes insipidus | Diabetes mellitus |

| Enteral nutrition | Goiter |

| Hirsutism | Hyperaldosteronism |

| Hyperandrogenism | Hyperparathyroidism |

| Hyperthyroidism | Hypoglycemia |

| Hypogonadism | Hypopituitarism |

| Hypothyroidism | Insulinoma |

| Nutritional support | Obesity |

| Pheochromocytoma | Prolactinoma |

Articles published in Spanish, English, and French were collected.

Historical figuresAkhenaten, Egyptian pharaohAkhenaten, who started his reign as Amenophis IV, was an important Egyptian pharaoh of the 18th dynasty. He reigned 17 years, from 1365 to 1348BC. Akhenaten made radical changes in Egypt: he established a new capital and, above all, founded a new monotheistic religion with a god called Aten, which represented a radical rupture with prior polytheism. The new religion was associated to a pacifist philosophy and a deep respect for nature, and also to a new concept of art in which sculptures or reliefs portraying the pharaoh were no longer highly idealized.2

This new, less idealized concept of art has led to many medical interpretations about Akhenaten, who is often portrayed as a person with marked bones and prominent jaw, sunken chest, bulky abdomen, and gynecoid fat distribution. In addition, his skull appears deformed.3 Many of the various diseases attributed to pharaoh Akhenaten based on the physical characteristics depicted in sculptures and reliefs are within the scope of Endocrinology and Nutrition. Thus, several authors have suggested that Akhenaten suffered from acromegaly, with or without hypogonadism, isolated hypogonadism, or rickets, and even gender dysphoria, which would have led to portray him as a womanish figure with no male genitalia.3 Other proposed diagnoses include Klinefelter syndrome4 or lipodystrophy,2,3 especially a cephalothoracic form which would partly explain the facial configuration, marked collarbones, loss of subcutaneous fat layer, increased hip fat, and hepatosplenomegaly and eventual cirrhosis with bulging.2

Maximinus I, Roman emperorGaius Julius Verus Maximinus was a Roman emperor of the 3rd century. He was born in a remote Thracian village and was a shepherd as a child, but was soon recruited for the army because of his size and strength. After a meteoric military career, in which he commanded legions and provinces, he was proclaimed emperor by his soldiers, who killed his predecessor, Alexander Severus.5 His reign lasted three years, and he was finally murdered by his own soldiers. This led to a time of anarchy which lasted until emperor Diocletian ascended the throne.

The size of emperor Maximinus was legendary. According to Historia Augusta he was approximately 239cm in height, drank large amounts of fluid, and had profuse sweating. His image in denarii coined during his reign shows marked prognathism and growth of the superciliary arch. His sculptures also show acral growth. These characteristics (tall height, much greater than that of his contemporaries, acral changes, excess sweating, and polydipsia possibly related to diabetes mellitus) have led to suggest that emperor Maximinus I was an acromegalic giant.6

Bodhidharma, founder of zen buddhismBodhidharma, the third son of an Indian king, became a monk and in 527AD took to China a new form of buddhism characterized by meditation and self-deprivation. He moved to the Shaolin monastery in China, where he found monks to be n a poor physical condition and an easy prey for bandits. Since monks were forbidden to use weapons, Bodhidharma developed a system to fight without weapons which, over time, would lead to kung fu in China and karate in Japan. The religious system started by Bodhidarma represented to foundation of zen buddhism. Bodhidharma is said to have introduced green tea (on which patients often ask questions at endocrinology offices) in China to help him and his disciples to stay awake during meditation. According to another story, Bodhidharma always had his eyes open, so that he was able to see and know everything. Although a distinction between historical facts and legends is impossible, there is no doubt that Bodhidharma was a historical figure of the 6th century. In sculptures and portraits in zen temples, Bodhidharma has the typical appearance of Graves’ ophthalmopathy, with eyes open and bulging. This has led to suggest that he suffered from this ophthalmopathy, probably alone, with no thyroid involvement.7

Sancho I, king of LeonSancho I (935–966) was king of Leon and is known in history by the nickname of the Fat. He was the son of king Ramiro III and the grandson of queen Toda of Pamplona. There is no evidence that he had any relevant health problem at least until he was 20 years old.8 Sancho ascended the throne in 956, but was deposed two years later by the nobility, headed by count Fernán González, arguing that his extreme obesity prevented him from fulfilling the obligations of his post,8–10 and was succeeded in the throne by Ordoño IV the Evil.

Sancho I then took refuge in Pamplona, and asked her grandmother, queen Toda, for help. Queen Toda, in turn, requested the caliph of Cordoba, Abderrahman III, to whom she was bound by ties of blood, that his physicians helped Sancho treat his obesity, so that he could recover the throne. The caliph demanded that treatment was given in Cordoba, and Sancho I and Toda therefore traveled there. We do not know what was the treatment administered to Sancho by SD Hasdai ibn Shaprut, a jew born in Jaen who was both a good physician and.8 It has been suggested that theriaca was used10; the Chronicon Sampiri, written 200 years after the facts and quoted by García Álvarez,8 states that “King Sancho, as he was very fat, was offered by the moslems a herb and [with it] removed the fatness of his belly”. The fact is that the king lost weight and could recover the throne two years after he was deposed. This was probably the first travel abroad to receive treatment for obesity. It should however be noted that it has also suggested that Sancho had no obesity, but ascitis.8

William the Conqueror, king of EnglandWilliam, an illegitimate son of Robert, duke of Normandy, was born in 1028 and succeeded his father when he died. In 1066 William defeated the English king, Harold of Wessex, at the battle of Hastings, and thus became king of England, starting Norman control over this country.11

William, who had been a muscular man, developed a marked obesity, to the point that king Philip of France said that he looked as a woman about to deliver a baby. This insult served William as an excuse to draw up in battle array against Philip of France. In the battle, in 1087, William fell from his horse and suffered internal injuries which finally caused his death.11

Enrique IV, king of CastileEnrique IV, known in history as the Impotent, was born in 1425. He was the son of Juan II and succeeded his father on 1454, at the age of 29 years. He married Blanca de Navarra, whom he repudiated, and subsequently married Juana de Portugal, who gave him a daughter also called Juana, known as the Beltraneja because he was thought to be the daughter of Beltrán de la Cueva, the royal favorite, although Enrique always considered her his daughter. The 20 years of his reign may be divided into two clearly differentiated periods, each lasting approximately 10 years. In the first period, his authority was undisputed. In the second period, the nobility rose in arms against recognition of his daughter Juana as heir; Enrique IV agreed a peace pact with his enemies and designated his sister, Isabel, as his heir, thus somehow recognizing that princess Juana was not his daughter. The marriage of Isabel with Fernando de Aragón upset the king, who designated Juana as his heir again. This opened a new period of confrontations which resulted, after his death on 1474, to a civil war between the supporters of Juana and Isabel eventually leading to the crowning of Isabel I as queen of Castile.12

Reams and reams have been written on whether Enrique IV was impotent or not, the cause of such impotence, and whether Juana la Beltraneja was his daughter or not. What authors of the time reported us is that Enrique could not consummate his first marriage. After Blanca de Navarra was repudiated, as reported by Sitges, quoted by Maganto Pavón,13 “two honest duennas, married matrons swore that the princess was an incorrupt virgin as she had been born. As regards physical appearance, he was a person”–says Enríquez del Castillo, quoted by Marañón14–“long in height and thick in body, and with strong limbs; he had big hands and long and tough fingers; with a fierce appearance, looking almost like a lion, scaring those who looked at him; a snub and very flat nose, not that he was born with it, but because of an injury when he was a child; his eyes blue and somewhat spread, his eyelids red; he had a long staring gaze; the head big and round; a broad forehead; high eyebrows; sunken temples; long and hanging jawbones; thick and closed teeth; blond hair; long and seldom shaved beard; face complexion between red and brown; very white flesh; very long and proportioned legs; delicate feet”. On the other hand, according to Palencia, quoted by Marañón,14 “he was upset by any pleasant smell and, by contrast, inhaled with delight any fetid smell of decay, the stink of cut horse hooves, and burned leather, and other even more nauseating smells”. The mummy of Enrique IV was exhumed in 1946. Gregorio Marañón, who witnessed the exhumation, estimated that he should have been 1.80m in height; that his chest diameter was similar to hip width; that his head and skull should have been big and strong, with a broad forehead, separated orbital cavities, and prognathism; strong but poorly implanted feet; hands with long, strong fingers; and markedly long legs in proportion to trunk height and converging at thigh level: and finally, that the king had pes valgus.12

Marañón held that impotence of the king was true, but only relative, and he could have had occasional sexual intercourse, have got queen Juana pregnant and, thus, be the father of Juana la Beltraneja.14 Marañón also suggested a potential homosexuality; he stated that diagnosis of the king was “eunucoid dysplasia with acromegalic reaction”,14 in which hypogonadism would lead to a response of increased growth hormone secretion by the pituitary gland (which is poorly consistent with current knowledge of neuroendocrinology), and considering this dysplasia “rather than frankly pathological, as a constitutional and hereditary condition, similar to an eunucoid status, but closer to normality”.14 Attention has been drawn to the “liking” of the king for foul smells, which may have been due to anosmia caused by compression by a hypothalamic-pituitary tumor; the Maestre de San Juan-Kallman syndrome has been considered unlikely.15 Other authors ruled out the hypothesis of hypogonadism, mainly because the king had “a long, seldom shaved beard”, and propose a diagnosis of acromegaly mainly based on physical description física.16 Finally, some state that no reliable data suggesting that Enrique IV suffered hypogonadism or acromegaly are currently available, but repeat examination of the mummy using radiographic techniques, mainly in sella turcica and limbs, could cast new light on the subject.17

Henry VIII, king of EnglandHenry VIII was born in 1491 and is considered as one of the most important kings of England. He is famous for marrying six women and for establishing the Anglican Church after breaking away from the Roman Catholic Church. In his youth, Henry VIII was healthy; he was an enthusiastic horseman and hunter, and participated in tournaments. However, his physical condition gradually worsened, and he developed morbid obesity, depression, and ulcers in both legs. This decline in health appeared to occur after an accident he sustained at the age of 44 years, which left him unconscious for two hours. He died in 1547 with supermorbid obesity, syndrome of immobility, and heart failure. It has been suggested that the reason for this impairment after the accident would be growth hormone deficiency secondary to head trauma. This deficiency would explain weight increase, mood changes of the king, and difficult healing of ulcers in the lower limbs secondary to chronic venous insufficiency related to obesity.18

Mary I, queen of EnglandMary Tudor was born in 1516. She was the daughter of Henry VIII of England and Catalina de Aragon and, thus, a granddaughter of the Catholic Monarchs. After Henry VIII broke away from the Roman Catholic Church, Mary was removed from the line of succession for eight years, but finally ascended the throne at the death of his brother Edward in 1553, when she was 37 years old. In 1554 she married prince Felipe, son of Carlos I and future king Felipe II, who was a widow at the time and had a legitimate son, prince Carlos, and several bastard sons. They were proclaimed “Felipe and Mary, by the grace of God, king and queen of England, France, Naples, Jerusalem, Ireland, champions of faith, princes of Spain and Sicily, archdukes of Austria, dukes of Milan, Burgundy and Brabant, and counts of Habsburg, Flanders, and the Tyrol”.19

Mary had a fragile health. Authors suggest that she could have had congenital syphilis19,20 and an often depressive mood.19,20 Since the age of 19 years, she experienced oligomenorrhea and frequent headache, and had two false pregnancies during which, in addition to amenorrhea, she experienced breast volume increase and even galactorrhea. Her visual acuity was low, and she had to take the paper very close to her eyes to be able to read. She also had eyebrow loss, a deep voice, dry skin, and constipation. Together, these signs have led to propose that queen Mary had a prolactinoma which, due to a mass effect, would have caused secondary hypothyroidism and optic tract compression.19,21 Mary of England died at 42 years of age, maybe as the result of a flu epidemic,20,21 although the pituitary tumor may have contributed to death.19

Carlos II, king of SpainKing Carlos was born in 1661. He grew up as a weak, sicky child with psychomotor delay. He was breastfed by 14 wet nurses until the age of 4, did not walk until he was 8 years old, and did not speak intelligibly until the age of 10 years.22 He married twice, at 18 and 29 years, and had no children.23 He died in November 1700 with no descendants, which led to the Succession War.

Autopsy revealed “a heart the size of a pepper grain, swamped lungs, rotten and gangrenous bowels, three big stones in the kidney, a single testis black as coal, and the head full of water”.24 Historians have suggested that the close consanguinity in the Habsburg dynasty could have been the origin of the health problems of Carlos II and, eventually, of the extinction of his lineage. Endocrine diseases have been considered to be responsible, at least partly, for the health and infertility problems of Carlos II. Marañón suggested a diagnosis of panhypopituitarism with progeria22; Klinefelter syndrome has also been cited,24 and other authors have proposed genetic panhypopituitarism of autosomal recessive inheritance.23 He would also have rickets.24

Pío de Jesús Pico, governor of Alta CaliforniaPío de Jesús Pico, better known as Pío Pico, was born in 1801. He was Governor of the Alta California province under Mexican sovereignity in two time periods, first in 1832 and then from 1844 to 1846.25 Since in 1848, after Mexico was defeated by the United States, the territory was transferred to this country, Pío Pico was the last Mexican governor of the current state of California. After this transfer, Pío Pico returned to Los Angeles and became a citizen of the United States and a rich owner of real estate and livestock. However, several unfortunate business operations and legal actions for fraud ended with his fortune and caused him to pass his final years as poor as he was born.26

Several daguerreotypes and oil paintings portraying Pío Pico at 46 and 60 years of age suggest that he suffered acromegaly: they show an individual with a broad forehead, broad nose, prominent lips, mandibular prognathism, and hands with very broad fingers. In addition, the dysconjugate gaze shown by the images, the lack of children at a time when marriages used to have a numerous offspring, and the fact that he appears with no mustache or beard support the hypothesis of acromegaly due to a pituitary macroadenoma invading cavernous sinus, which would have caused oculomotor palsy and hypogonadism.26

Surprisingly, in later images taken when Pío Pico was already in his ninth decade of life, acromegalic features were not so obvious and he shows thick beard and mustache. It has therefore been suggested that he could have suffered pituitary apoplexy which spontaneously cured his acromegaly,26 as has been reported in some patients.27 A fact that would also support self-cure of Pío Pico is that he died at 93 years, a very advanced age for a person with acromegaly.

Pedro II, emperor of BrazilPedro II was born in 1825 and crowned in 1841. During his reign, trade of blacks was abolished in Brazil, in 1850, an act for gradual emancipation of slaves was passed in 1871, and slavery was abolished in 1888. These measures gained him the disaffection of some sectors affected, which promoted a change in regimen. Decimal metric system and telegraph were also introduced in Brazil during his reign, 18,000km of rail track were laid, and public education, universal vote, and progress of arts and science were promoted. In 1889, after Brazil became a republic, he was forced to exile, and died in Paris two years later.28

Pedro II suffered type 2 diabetes mellitus. In 1883 he was diagnosed with glycosuria. The emperor aged prematurely, and with 60 years he looked like a 70-year-old man, had an unstable gait and almost dragged his feet. The hypothetical intellectual decline of Pedro II was used as a political weapon, but his impairment was probably physical, rather than mental. In 1887 he traveled to Europa, where he was seen by physicians such as Bouchard, Brown-Séquard, or Charcot. During his stay in Europe he may have experienced a transient ischemic attack, and gangrene in a toe, which was resolved. He also had urinary incontinence and weakness in lower limbs. These data have led to infer that emperor Pedro II had chronic complications of diabetes such as macroangiopathy, peripheral neuropathy and, probably, transient ischemic attacks, and that all of this contributed to establishment of the republic.29

Dwight David Eisenhower, president of the United StatesEisenhower was born in 1890. When the United States entered World War II, Eisenhower was an army general, and was appointed as commander of the US troops in Europe. He was responsible for planning the military landing operations in North Africa, Italy and, mainly, in Normandy on June 6, 1944. He left the army after World War II, and in 1952 he run in the election for president of the United States. Eisenhower won the election, and was invested as the 34th president of the United States on January 20, 1953. One of the initiatives during his term of office was the creation of a Department of Health, Education, and Social Affairs. In 1956 he was re-elected as president for a second term, lasting from 1957 to 1961.30

Eisenhower had eight heart attacks before he died from ischemic heart disease in 1969, at 78 years, almost 15 years after his first heart attack. He had been diagnosed with labile or transient hypertension. When he was 40 years old, his clinical history already included blood pressure values of 164/94mmHg. Between 1944 and 1945, when he was the supreme commander of allied forces, he probably received antihypertensive medication. But it was especially during the last years of his life when he had blood pressure values of approximately 200/120mmHg. He also suffered episodes of headache associated to blood pressure increase. The autopsy performed after his death revealed a previously unknown 15mm pheochromocytoma in his left adrenal gland.31

John Fitzgerald Kennedy, president of the United StatesJohn Fitzgerald Kennedy was born in 1917. He grew up in a multimillionaire family and participated in World War II. His political career started after the war. He was a congressman and senator, and in 1961 became the 35th president of the United States, the youngest elected and the first catholic to reach the presidency. Events occurring during his presidency included the failed invasion at Bahía Cochinos, the missile crisis, and the start of the race to take man to the moon. Kennedy was murdered in Dallas in 1963.32

As regards his health, he was performed basal energy expenditure studies in 1935 and 1939 with results in the lower normal limit. In 1945, when he announced his candidacy to Congress, he was very thin and had a weak appearance. As the campaign progressed, Kennedy appeared tired, with sunken eyes and an “anemic appearance” according to his collaborators, and in 1946 he suffered a collapse after a five-mile walk. In September 1947 he fainted during a stay in England. He was then diagnosed with an Addisonian crisis, and upon returning to the US he was prescribed treatment with deoxycorticosterone acetate, which was implanted as pellets under the skin of his arm every three months. When oral cortisone became available in the 50s, 25mg/12h of this drug were added to treatment with deoxycorticosterone acetate. Later, Kennedy was also treated with hydrocortisone, prednisone, and fludrocortisone. He underwent back surgery in 1954, and his case was anonymously reported in an article on management of adrenal insufficiency during surgery published in Archives of Surgery.33 In 1955 he was diagnosed with primary hypothyroidism, and started treatment with liothyronine 25mcg/12h. In addition, Kennedy was treated with different testosterone preparations throughout his presidency. As he had four children, it is unlikely to have suffered severe hypergonadotropic hypogonadism, and it has been speculated that he could have partial inhibition of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis due to continuous corticoid intake, or even that he could have developed hypogonadotropic hypogonadism as the result of autoimmune hypophysitis. Treatment with testosterone was maybe prescribed to improve his weight and muscle mass. On the other hand, Kennedy suffered gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, and difficulty to gain weight for a great part of his life, and received treatment with vitamin B12, but was not diagnosed with celiac disease or chronic gastritis. His family history included a sister with Addison's disease and a son who developed Graves disease. The autopsy performed after his murder found virtually no adrenal tissue, which was consistent with adrenal atrophy, and no evidence suggesting destruction of the adrenal gland by tuberculosis. Although autoimmunity parameters are not available, family history of autoimmune endocrine disease, presence of non-tuberculous Addison disease together with primary hypothyroidism, and potential coexistence of atrophic gastritis and hypogonadism have led to propose that Kennedy had polyglandular autoimmune syndrome type 2.34

Other historical figuresTable 2 lists other people whose biographic and health cannot be addressed here for reasons of space.

Other historical figures who may have suffered endocrine diseases.

| Ankhesenamun (14th century BC.), daughter of Akhenaten, wife of Tutankhamen. Goiter36 |

| Dionysius (4th century BC.), tyrant of Heraclea Pontica. Obesity, sleep apnea syndrome37 |

| Herod the Great (73BC–4AD.), king of the Jew. Diabetes mellitus38 |

| Fernando I (1431–1494), king of Naples. Obesity, carotid atherosclerosis39 |

| Mary I (1542–1587), queen of Scotland. Anorexia nervosa40 |

| Michelangelo Merisi de Caravaggio (1569–1610), painter. Acromegaly41 |

| Maria de Medici (1573–1642), queen of France. Diabetes mellitus, diabetic ketoacidosis42 |

| Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (1606–1669), painter. Hypothyroidism, hypercholesterolemia43 |

| María Josefa de Borbón (1744–1801), daughter of Carlos III of Spain and sister of Carlos IV Hyperthyroidism44 |

| Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827), musician. Diabetes mellitus45 |

| Otto von Bismarck (1815–1898), German military man and statesman. Obesity46 |

| Mary Todd Lincoln (1818–1882), wife of Abraham Lincoln. Diabetes mellitus, diabetic neuropathy47 |

| James Abram Garfield (1831–1881), president of the United States. He received enteral nutrition by the rectal route after a bullet wound48 |

| Elizabeth of Austria (“Sissi”) (1837–1898), empress of Austria. Eating disorder49 |

Retrospective diagnosis of diseases of historical figures has often been criticized on the grounds that it is only an assumption, frequently based on some insufficient data.19 The older the figure and the less reliable the available data, the more mistaken may diagnosis be.

It is obvious that other historical figures not appearing in medical literature may have suffered endocrine diseases. This review may not have been comprehensive, and another search strategy would possibly have found more publications on the subject.

The diagnoses proposed for Herod the Great, Maximinus I, and Sancho I are based on descriptions by historians who did not known them directly. Diagnosis based on painting or sculptures depends on fidelity of the artist to reality. Thus, for example, sculptures of other court and family members show characteristics similar to those of Akhenaten. This could therefore be a new form of representation of the human figure, rather than a realistic representation of the pharaoh.3 The study of the remains of the Akhenaten mummy showed no gynecoid characteristics in the pelvis or the skull deformities seen in statues and reliefs, and no sellar area widening was found.35 It should be noted, however, that sella turcica may be greatly damaged when brain is taken out during the mummification process.3

Diagnoses of more recent historical figures, based on necropsy studies or on clinical descriptions or histories provided by physicians who cared for them, are obviously more reliable. However, although a certain diagnosis cannot be established, the symptoms described for personages such as Enrique IV of Castile or Mary I of England make presence of some endocrine disease likely.

On the other hand, if one admits that the abovementioned historical figures suffered endocrine diseases, it is exciting to wonder how these conditions may have affected history. I will refer to two cases. If Enrique IV had not been impotent (admitting that he had impotence and this was due to an endocrine disease), there would have been no doubt that he was the father of princess Juana, and even he would probably have had more children. Isabel would therefore not ascended the throne, the crowns of Castile and Aragon would not have united, and the first Columbus travel would not have been funded by Castile. Thus, the world would be today different from the one we know. Similarly, if Mary of England and her husband Felipe II had had a child, he/she would have inherited the English and Spanish crowns (including European and American possessions).19,21 That is, a monarch would have reigned over virtually all Western Europe and the whole American continent between the 16th and 17th centuries, with unforeseeable consequences for our present.

In conclusion. the medical literature has reported, with more or less success, that a number of historical figures suffered endocrine diseases. Knowledge of these figures may contribute to practice differential diagnosis and to motivation of undergraduates and graduates training in endocrinology and nutrition.

Conflicts of interestThe author states that he has no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Alfaro-Martínez JJ. Personajes históricos en la consulta de Endocrinología. Endocrinol Nutr. 2014;61:382–388.

To the memory of Dr. Lorenzo Abad Martínez, professor of Gynecology at the School of Medicine of Universidad de Murcia, who awoke in me interest in Endocrinology and the disease suffered by historical figures in the past.