We report the case of a 51-year-old female patient who first attended the Endocrinology Department 4 years ago for hypoglycemic episodes, some of them with neuroglycopenic clinical symptoms. The episodes started with adrenergic symptoms (tremor, sweating, intense hunger), but occasionally evolved to, or included from the start, confusion and presyncope with fall. Suspected hypoglycemia was verified with a reflectometer, which showed values ranging from 30 to 40mg/dL. The patient reported that hypoglycemia occurred at all times of the day, but most frequently after meals. She had no medical or surgical history of interest, and the only drug she was taking was tibolone for menopausal symptoms. Her family history only included type 2 diabetes mellitus in her mother.

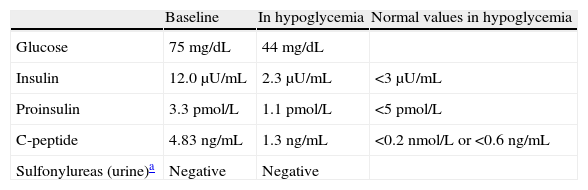

She was referred to hospital for work-up. A first fasting test only showed hypoglycemia at the end of the third day (44mg/dL), and non-suppressed C-reactive peptide during the episode (1.3ng/mL) as the only relevant finding (Table 1).

Fasting test values.

| Baseline | In hypoglycemia | Normal values in hypoglycemia | |

| Glucose | 75mg/dL | 44mg/dL | |

| Insulin | 12.0μU/mL | 2.3μU/mL | <3μU/mL |

| Proinsulin | 3.3pmol/L | 1.1pmol/L | <5pmol/L |

| C-peptide | 4.83ng/mL | 1.3ng/mL | <0.2nmol/L or <0.6ng/mL |

| Sulfonylureas (urine)a | Negative | Negative |

The finding of non-suppressed C-reactive peptide in hypoglycemia led to several imaging tests being requested to search for an insulinoma. Among these, a CT scan and pancreatic MRI showed no findings, and an octreoscan was negative. A first ultrasound-guided endoscopy was negative, but a second endoscopy revealed a 9mm×10mm lesion in the tail of the pancreas which was found to be ectopic spleen in fine needle aspiration.

The patient continued to experience severe hypoglycemic episodes, for which surgery was decided on so as to identify and resect a potential insulinoma despite negative localization tests. Partial pancreas tail resection was performed in October 2007. Pathological examination of the pancreatic specimen found diffuse beta cell hyperplasia consistent with nesidioblastosis.

After surgery, the patient remained asymptomatic, with no hypoglycemic episodes, for approximately 1 year.

In August 2008, the patient returned for consultation reporting less severe clinical symptoms of hypoglycemia with no neuroglycopenia, which she controlled with a continuous intake of small amounts of carbohydrates. New imaging tests (CT and ultrasound-guided endoscopy) were requested, and the results were again negative. Due to the suspicion that the first surgical excision had not been wide enough or had not been performed in the most affected pancreatic territory, the patient was referred to another center for an intra-arterial calcium stimulation test through interventional radiology. A second fasting test was performed there and was totally negative (with no hypoglycemia at any time and adequately suppressed C peptide and insulin). The subsequent intra-arterial stimulation test showed the results summarized in Table 2: basal insulin levels were doubled or tripled in all three arterial territories studied.

Because of these results, General Surgery was contacted again and repeat surgery was performed, this time through corporocaudal splenopancreatectomy. The pathological laboratory again reported pancreatic islet hyperplasia and hypertrophy consistent with adult diffuse nesidioblastosis.

The patient experienced no new hypoglycemic episodes after surgery, but developed pancreoprival diabetes mellitus and required therapy with insulin glargine 20IU, with which optimum glycemic control was maintained.

The diagnosis of hypoglycemia should be based on the Whipple triad: symptoms of hypoglycemia, low glucose levels in venous blood concomitant with such symptoms, and symptom resolution after blood glucose increase. Adrenergic (sweating, tremor etc.) or neuroglycopenic (confusion, focal neurological signs, seizures, loss of consciousness) symptoms may occur. Adrenergic symptoms occur with blood glucose levels less than 60mg/dL and are relatively non-specific. The latter do not usually occur until blood glucose falls below 50mg/dL and are much more specific. Usually, the more severe the neuroglycopenia, the more likely is the hypoglycemic disorder due to hyperinsulinism.

Among the different classifications of hypoglycemic disorders, the most traditional one differentiates fasting from postprandial hypoglycemia (which occurs 4–5h after food intake). Once drug use has been ruled out, fasting hypoglycemia has usually been identified with organic disorders such as hyperinsulinism due to insulinoma, end-stage liver disease, contrainsular hormone deficiency, or large mesenchymal tumors, while postprandial hypoglycemia has more commonly been related to “functional” disorders such as prediabetes or nutritional hypoglycemia in patients undergoing upper gastrointestinal tract surgery. The latter are related to rapid gastric emptying or dumping syndrome. This old classification does not include noninsulinoma pancreatogenous hypoglycemia syndrome (NIPHS), first reported more than a decade ago and suffered by our patient.

NIPHS is a syndrome characterized by endogenous hyperinsulinism not caused by an insulinoma. It is clinically characterized by the occurrence of hypoglycemia with neuroglycopenia in the postprandial period, negative fasting test (although there are exceptions in cases reported in the literature), imaging tests negative for insulinoma, and positive intra-arterial calcium stimulation test in one or several of the pancreatic arterial territories studied.1 Unlike insulinoma, NIPHS is more common in males. In these patients, pathological study reveals beta cell hypertrophy, islets with enlarged, hyperchromatic nuclei, and increased periductal islets, histological findings typical of nesidioblastosis and similar to those seen in newborns and small children with persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia. In children, these changes have been related to mutations in the Kir6.2 and SUR1 genes.2 However, these mutations are absent in reported cases of adults with NIPHS.1 The pathogenesis of NIPHS in adults is still unknown, but overexpression of the human cytokine INGAP, which is involved in islet neogenesis, has been reported in pancreas resected from these patients.3

It is not known whether pathological findings may directly be correlated to this clinical syndrome, because subtle changes similar to those occurring in nesidioblastosis may be seen in up to 36% of autopsies of patients without hypoglycemia.4

Diagnosis of NIPHS should be suspected based on episodes of hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia with both negative fasting and insulinoma localization tests. Since the fasting test is usually negative, hyperinsulinism may be diagnosed based on either spontaneous hyperglycemia seen at the clinic/hospital or on hyperglycemia induced by a mixed meal test, for which the patient eats a meal similar to the one that causes the symptoms at home and is subsequently monitored for five hours, with samples for glucose, insulin, C-reactive peptide and proinsulin measurements being collected every 30min. Once hyperinsulinism in hypoglycemia is shown, and provided imaging tests for insulinoma are negative, an intra-arterial calcium stimulation test is indicated. This latter test consists of the infusion of calcium gluconate, a secretagogue for the pathological beta cell, into the arteries supplying the pancreas (superior mesenteric, gastroduodenal, and splenic arteries) and the collection of samples for insulin testing from the hepatic veins. The stimulation test is considered positive if basal serum insulin levels are doubled or tripled. This only occurs when the artery(ies) supplying the pancreatic region with hyperfunctioning islets due to either insulinoma or nesidioblastosis is infused, and does not occur when a normal pancreatic territory is infused. In occult insulinomas, the test is usually positive for the arterial territory supplying the tumor only, while in NIPHS it is usually positive for multiple territories, as occurred in the reported patient.5

The treatment for severe hypoglycemia is surgery and consists of pancreatectomy, which may be partial, subtotal or, ideally, guided by the calcium test gradient. This involves resecting the pancreatic territory to the left of the superior mesenteric vein when the test is only positive following infusion into the splenic artery, and extending resection to the right of the superior mesenteric artery when the test is positive following infusion into any other additional artery.1 In most cases, even non-total pancreatectomy abolishes or significantly improves hypoglycemia, but recurrences have been seen after partial pancreatectomy.6,7 In our patient, the first distal pancreatectomy, performed “blindly”, that is, without an intra-arterial calcium stimulation test, turned out to be clearly insufficient in the long-term.

As regards medical treatment options, there are reports in the literature of cases successfully managed with octreotide, verapamil, and diazoxide,8 but surgery is usually recommended in patients with severe hypoglycemic episodes.

Patients who develop postprandial hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia years after undergoing bariatric surgery are another group in which nesidioblastosis is often found in the surgical specimen from partial pancreatectomy.

Etiopathogenesis of the disorder has not been completely elucidated in these patients either, but several mechanisms have been postulated: the presence of prior changes in beta cell function which had remained masked and asymptomatic because of insulin resistance in obesity, or pathological beta cell hyperplasia in response to certain humoral factors which are increased following gastric bypass. Specifically, an excessive increase in GLP-1 in response to a mixed meal has been seen in patients with this complication, unlike patients undergoing bypass who have not experienced hypoglycemia.9

Some common pathogenetic link may possibly exist between spontaneous NIPHS and nesidioblastosis secondary to bariatric surgery, but such a link has yet to be found. To date, increased growth factor and growth factor receptor levels only have been reported in pancreas from patients of both types as compared to control pancreas.10

To sum up, although fasting hypoglycemia is the usual presenting symptom of hyperinsulinism, there are some cases with postprandial hypoglycemia, particularly when this is severe and associated with neuroglycopenia, which should lead us to consider the existence of nesidioblastosis, not only in patients undergoing bariatric surgery, but also as a spontaneous phenomenon.

Please cite this article as: Antón Bravo T, et al. Hipoglucemias posprandiales. Endocrinol Nutr. 2012;59:331–3.