Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) is a genetic disorder characterized by bone fragility, usually due to a mutation in the COL1A1 or COL1A2 genes that encode for the α chain of type 1 collagen, the main bone protein.1–4

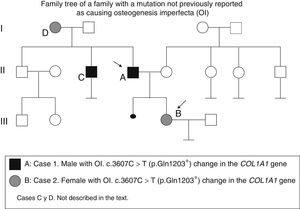

Two patients with OI (father and daughter) in whom a genetic study showed a c.3607C>T (p.Gln1203*) change in the COL1A1 gene not previously described are reported here. The potential reproductive options are reviewed.

Case 1This was a 55-year-old male diagnosed with OI after his affected daughter was born (Fig. 1). He had sustained at least 10 fractures and several dislocations before reaching 14 years of age. The patient had been diagnosed with mixed hearing loss. Physical examination findings showed the following: height 158cm, blue sclerae, normal teeth, no bone deformities. Laboratory test results showed: normal calcium, phosphorus and creatinine levels; 25OH-vitamin D, 16ng/mL; iPTH, 65.7pg/mL (NR, 15–65); 24h calcium levels, 260mg.

Normal bone density as measured by densitometry (DEXA) gave a mean T-score in the lumbar spine (LS) –2.2 (–3.7 in L4). Treatment with alendronate plus calcium and vitamin D was administered with a good response (T-score in LS after four years of treatment, –0.9).

A genetic study revealed a c.3607C>T (p.Gln1203*) mutation in the COL1A1 gene.

Case 2This was a 21-year-old female, the daughter of the above patient, who was diagnosed with OI at birth. During pregnancy, curved tibiae and intrauterine growth retardation were detected (birth weight, 2kg). She sustained her first fracture at four days of life, and subsequently had several fractures, especially in the lower limbs, before the age of 16 years.

At the age of seven years, DEXA showed a Z score −2.83 in LS; intravenous pamidronate and subsequently oral alendronate were administered until 14 years of age and an increased Z score to +1.2. Z score has remained normal since then. Physical examination findings were as follows: height 157cm, blue sclerae, normal teeth, no deformities, and normal hearing.

As she was concerned both about the way in which her disease was inherited and about her options for a future maternity, a directed genetic study was conducted, which confirmed that she carried the mutation previously detected in her father. Genetic counseling was provided.

Bone fragility is the main characteristic of OI, causing multiple fractures with no or minimal trauma, and progressive deformities in more severe cases. Other signs include low height, blue sclerae, dentinogenesis imperfecta, and hypoacusis in adults.

Diagnosis is usually made at an early age. In children and adolescents, intravenous bisphosphonates have been shown to be effective for decreasing fractures and improving pain, mobility, and final height. However, many patients reach adult age undiagnosed. Most adults affected have osteoporosis, for which bisphosphonates are the treatment of choice.5–7

OI is usually caused by mutations in genes that encode for the α1 and α2 chains of type 1 procollagen (COL1A1 and COL1A2 genes) and is inherited as a dominant autosomal disorder, although other genes have also been identified as being involved, including CRTAP and LEPRE-1, which result in uncommon forms of the disease with a recessive autosomal heredity. At least other 11 related genes are known, including OSX, SERPINH1, PPIB, FKBP10, BMP1, CREB3L1, IFITM5, SERPINF1, SPARC, TMEM38B, and WNT1.3,4,8

More than 1500 different mutations have been reported. Our patients were found to have a c.3607C>T (p.Gln1203*) mutation in the COL1A1 gene that implies a change in amino acid and glutamic acid by a stop codon at position 1203, resulting in a truncated protein. This nucleotide substitution has not previously been reported in the literature as being associated with OI, but based on the harmful effect it has on the protein, it is likely to be its cause.

The woman was informed of the dominant inheritance and of the risk of transmission of the disease (50% in each pregnancy). In cases where this condition is identified, genetic counseling is followed by information about reproductive options.9,10 In this case, the alternatives were as follows:

Preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD): after in vitro fertilization treatment, this allows for genetic embryo testing and for selecting healthy embryos. The mutation responsible for the disease is known, and one of two embryonic blastomeres is taken by embryo biopsy. Molecular genetic diagnosis is performed to search for the known mutation in the embryos, and non-affected embryos are selected to be transferred to the uterus, which allows for a child to be born without the genetic disease. PGD has been possible in Spain since the approval of Act 14/2006, of May 26, on assisted human reproduction techniques, and is available on the national health system. The main argument for performing PGD is that it prevents the trauma of miscarriage and decreases the stress associated with waiting for the results of prenatal diagnosis. It is however a long process associated with low effectiveness rates (15–20%) and high multiple pregnancy rates, potential embryo handling, controversy regarding the safety of embryo biopsy, and high cost.

In vitro fertilization with donor oocytes: the gamete of the affected parent is replaced by an anonymous healthy gamete. Oocytes and sperm are fertilized outside the uterus, and the embryo is transferred to the uterus of the mother, where it is implanted, free of disease.

Conception and the performance of prenatal diagnosis using procedures such as chorion biopsy and genetic amniocentesis, which allow for taking fetal cells on which genetic studies of OI may be performed. If the fetus carries the mutation, no cure exists. The only possibility is therapeutic abortion.

Non-invasive procedures such as the detection of fetal circulating DNA in maternal blood, are promising.

Other options for having a child include natural pregnancy accepting the risks entailed, or adoption.

Our patient is currently considering the pros and cons of these alternatives.

Women with OI who receive treatment with bisphosphonates during childbearing age also worry about their safety in future pregnancies, because these drugs remain for years in the bone matrix and cross the placental barrier. Bone turnover suppression may cause fetal hypocalcemia. Data in females are sparse, but no serious adverse effects have so far been reported.11 However, the safety period has yet to be established.

Please cite this article as: Pavón de Paz I, Gil Fournier B, Navea Aguilera C, Gómez Rodríguez S, Ramiro León MS. Opciones reproductivas en pacientes con osteogénesis imperfecta. A propósito de 2 casos de la misma familia con una nueva mutación en COL1A1. Endocrinol Nutr. 2016;63:367–369.